The Sons of Cain were gone. The Sons of Cain didn’t exist anymore. I watched the detachment go up in an IED south of Ramadi, our five-ton Humvees leaping in the air, the taste of metal on the back of my tongue. Stallings and Pearson. Ratchet-man and Lipsky. Captain Pollock who had a lisp and a stutter, but could still put the holy terror in the hajjis whenever we dropped a house. Griggs and the Cannibal. Warrant Officer Jenkins. D-Rock with the Big Cock, best team sergeant in Third Group. The bad guys detonated on our convoy and blew us to the clouds, eight out of thirteen of us DRT. It’s not the kind of thing you’re supposed to say about your own guys, but Camden kept saying it over and over. I pulled him to the side of the road by the drag handles on his vest. I turned back toward our smoking Humvee when he caught hold of my arm. His face was black with soot and I saw he was missing his top row of teeth. There was a bright fringe of blood on his lips and his pupils pointed in different directions.

“DRT,” he told me. “DRT.”

I tried to pull away, but he held on. Then his grip started to slacken, and a rattling noise came from deep in his throat, more metallic than man. He exhaled a long breath in my face, and then he went very still.

A gray steam rose from his uniform. He smelled like grilling meat. I began to murmur kaddish, then went staggering back to our vehicle to look for our communications sergeant, Stacks. I guess that’s what I was doing. Everything had gone sort of scrambled. My ears rang for three weeks and my entire body had the jangled sensation you get when you knock your elbow against a wall. There were fine grains of sand blasted under the glass of my watch. It was a Luminox Blackout, waterproof to 200 meters, and the grains of sand sparkled like diamonds. I looked up and saw Littlejack still sitting behind the wheel of our Humvee. I opened my mouth to speak to him when rounds started cooking off in the ammo box of the machine gun mounted on the vehicle’s right door. I dropped down and went prone in the dirt. Ditto was back in the rear Humvee, standing up in the gun turret behind the .50, standing on one leg because the other was a crushed sack of bone. He thought we were taking fire, so he began strafing the desert berms. We weren’t taking fire. Some fuck-knuckle had just daisy-chained three 155mm artillery rounds, waited until we were in the kill box, and then sent us to heaven. He might have been half a mile away, watching it all through binoculars. The .50 jammed, and things went suddenly quiet, and I turned to see Posner stumbling in circles, pouring a bottle of Aquafina in his face, saying, “I can’t see anything, Bix. Bix, I can’t see.” Shrapnel had severed the optic nerve of one eye and split the cornea of the other. He’d never see anything again.

I located Stacks, who looked fine on the outside, but we’d later discover the blast had ruptured his liver and spleen, and he died on the operating table at Camp Liberty. Ditto died a month later at Ramstein Air Base from infection, Josh the next year in a hotel room in Fayetteville. His injuries had sidelined his career in SF, and he put his .45 in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

My only injuries were hearing loss and a strain in my lower back from dragging Camden, all 230 pounds of him, plus gear. We’d been one of the most effective counterinsurgency teams in the Sandbox. ODA-3315, the Sons of Cain. Right Arm of the Apocalypse. The Airborne of Armageddon. And with the exception of me and Littlejack, we were gone.

Littlejack was released from the aid station the next day with a minor concussion, then they transferred him to Baghdad to work for Task Force 88. In a week, they’d moved me to another ODA, also Third Group, also central Iraq, but real Meat Eaters these guys, hunter-killers. With the Sons, I’d helped set up clinics and met with Sunni tribal leaders, passed out survival radios and vitamin packs, dug wells for villages and taught the locals how to treat their water. My new team’s call sign was Underchild, and all we did were raids. First Fallujah had just calmed down, and Higher feared we were losing control of the populace. I went from hearts and minds to kicking down doors in the middle of the night, black-bagging hajjis and handing them off to CIA analysts, these pudgy office-worker types with wire-rimmed spectacles and pistols they’d never draw strapped to their thighs.

After about two weeks of this, I went to our CO. He was a lieutenant colonel, and he’d had my same MOS during the Gulf War. Not many enlisted men end up as officers, and he’d been in Special Forces for most his career. I told him about what they had us doing. I told him about my time with the Sons. I told him Uncle Sam hadn’t sent me through selection, sniper school, the spec ops medic course, and sixty weeks of classroom training just to become a door kicker. They had the infantry for that. They had rangers and SEALs. The whole idea of Special Forces was unconventional warfare. We were supposed to be teachers, training locals for a guerilla campaign. Why use a scalpel to carve a turkey?

He sat there at his desk, listening patiently as I wore myself out. When I was finished, he looked at me and smiled.

“You doin’ okay, sergeant?”

“Yes sir,” I said. “I suppose.”

“You might not know it, but you’re with the best ODA in country. Maybe the best in the war. Your captain is a rock star. Your weapons sergeants are a couple of goddamned legends. They lost their senior medic last month, and you lost your team. You want my opinion, the two of you are a perfect fit.”

“Rock star,” I said.

“Absolutely,” he told me.

“Sir,” I said, “that’s kind of the problem. I’m sure this is the kind of sexy a lot of guys signed up for, but I didn’t sign up for sexy at all.”

“What’d you sign up for?” he asked. It wasn’t a rhetorical question. He really wanted to know.

I thought about this a few seconds. I didn’t want to say “to make a difference,” even if that was the truth. I mumbled something about how we weren’t going to win the hearts of the Iraqi people through violence of action.

“How long have you been with Captain Wynne?”

“Ten days,” I said. “You want to know how many raids I’ve been on?”

“Tell me.”

“Twenty-three. That’s two a day. Or more than two. Two-point-three. That’s more than I did my whole time with the Sons.”

“Well, Sergeant Bixby”—and I could see the shades going down behind his eyes—“it’s a new kind of war we’re fighting.”

“Yes sir,” I told him. “It absolutely is.”

He didn’t say it, but I think he was actually worried about keeping me safe. I’d walked away from an IED with little more than hearing damage, and I think he felt like I’d earned some protection, his idea being Captain Wynne was the best protection around. Fuck him, was my idea. I missed Captain Pollock. I missed my old team. ODAs are a family, and I suppose my new family would’ve been great if my last name was Manson.

Back in Seattle, I’d worked as an EMT. Then in the late nineties my buddy started a software firm and took me aboard as partner. I liked numbers and programs, formulas and logic. I’d been a good paramedic because my emotions were like something I watched on a monitor: Whenever I needed to, I could always switch them off. I learned it from my father. Or from being around my father, rather, who, after my mother died of cancer when I was three, was mostly zonked out on prescription pills. And aside from going to temple a few times a year, faith wasn’t something I worried about, that whole intuitive side of the brain. Data was more dependable. It was the main reason our software firm had done so well. My buddy was all instinct and passion; I could take those qualities and plug them into a business model. We were making more money than we could ever spend, and two weeks after 9/11, I walked down to the nearest recruiter and enlisted. My rabbi tried to talk me out of it, but I wouldn’t listen. It was probably the first irrational thing I’d ever done, but it hadn’t seemed that way at the time. I knew they were going to need medics; I didn’t even know what Special Forces was. Then after basic, I found myself in jump school at Benning, and then afterward, in the Q course at Bragg. I passed selection and they sent me through the special operations combat medic course, and by the end of 2003, I’d been assigned to an alpha team. We were force multipliers. We built democratic countries from the floor up. Take one Green Beret, insert him in a village, he trains a hundred men to fight. They train a thousand more. One man becomes an army. That’s unconventional warfare.

Captain Wynne was unconventional, all right. He had that part of it down. He had dark-blue eyes that glowed like sapphires. He had a business degree from Princeton, and had worked on Wall Street managing hedge funds. Like me, he’d joined the army after September 11, but when he did it, he did it smart. Went through officer candidate school. Was commissioned as a lieutenant. Went Special Forces and ended up as captain of his own team. He’d been a star quarterback in high school and he had that physical confidence only athletes possess, that physical intelligence and poise. Blond. Bearded. Good looking, of course. You looked at him and knew there wasn’t anything he couldn’t do; there wasn’t anything he wouldn’t. I sized him up for an egomaniac who’d get every one of us killed.

Our OP was at the end of this military supply route, right outside Fallujah. I remember it raining all that summer. Everything was mud. We shared the outpost with a company from the 509th, a crew of mortar operators, several platoons of infantry. They were quartered in a refurbished slaughterhouse, hooks still hanging from the stone walls, rows of two-by-four bunks on the bare concrete floor.

OP Roma, it was called. A fortress of twelve-foot barriers and concertina wire, a gate at the north end of the compound with plywood guard towers. Machine-gun emplacements up on the Hesco walls. In the southeast corner of the outpost, six prefab trailers that served as our barracks, each oblong white box seated atop concrete blocks. The air conditioning was cranked so high we wore gloves and watch caps indoors. The paratroopers providing security for the OP were either frightened by us or in awe, like zoo visitors walking past the lions’ den: curious and terrified all at once. We wore our hair long. We wore beards and Merrell hiking boots. No grooming standard. No rank insignia on our uniforms. Sometimes no uniforms at all.

Roma was one of seven outposts along the supply route, and insurgents took potshots at it all the time. My third week with Wynne’s ODA, I was playing horseshoes with Sheldon, our junior medical sergeant, when one of the paratroopers’ Humvees pulled up to the gate. The .50 cal gunner was standing up in the turret. He’d taken off his helmet. His Oakleys had that iridium finish, and they flashed in the sun. Sheldon’s horseshoe rang against the metal stake, and the gunner turned to look in our direction. I watched him reach into his chest rig, pull out a pack of cigarettes, light one, and inhale. He blew out a thick stream of smoke, blue in the evening light. Then the left half of his head disappeared in a dark crimson mist. A few seconds later the report of the gunshot reached us from the desert. The gunner’s body collapsed like a switch had been thrown, someone called “sniper,” and everything was chaos. The machine guns began belching fire from their positions on the walls, men sprinted for cover, men screamed orders. I dropped to my knees with my heart slamming in my chest, the pulse in my ears loud as an engine. A panic exploded in my temples and went coursing through my veins. My hands started to tremble. They’d never done that before. They hadn’t trembled the day our convoy blew up, but they were sure as shit trembling now.

I glanced over at Sheldon. He’d taken a knee and pulled his sidearm. He was young for Special Forces, twenty-two, twenty-three, and his beard was a patchy fluff of light-brown fur. He still had baby fat in his cheeks. The heat of Fallujah and performing two raids a night had yet to burn it off. He knelt there with his pistol, staring up toward the machine-gun emplacements. I followed his gaze and saw a soldier sprinting up the sandbag stairway, belts of ammunition hanging around his neck like a tallith, the most lethal prayer scarf ever knitted. He made the catwalk and had almost reached the gunner when the first mortar hit.

The enemy had ranged us in by that point, gone to work on us with indirect fire. The sniper’s shot was just the kickoff. Soon mortar rounds were detonating all over the outpost, and our own mortar crews were struggling to respond. The image of an anthill came to mind—an anthill some child had decided to blow apart with firecrackers. Our machine gunners were firing blindly from atop the walls. Then, as they ran out of ammo, the guns began to go quiet. It hadn’t ended well for the poor bastard who’d tried to resupply the .50. He hung upside down from the wall, one boot caught between the barriers, the rest of him dangling lifeless as a doll.

I’d gone just as limp. That had never happened before. In a firefight my brain had always run like a calculator: This action plus this action equals this result. Now those circuits were fried, and something rose up to strangle me like a fist. The one rational thought that presented itself was that if our machine guns didn’t get back online and start providing suppressive fire, the enemy mortars were going to rip us to pieces.

I saw something move from the corner of my eye: a man jogging toward the stairway. It was Captain Wynne. He must’ve been woken by the mortars and come straight from his rack—the entire team took its sleep whenever it could—because he wore nothing but a pair of black PT shorts and his Yankees ball cap. At first I thought he was barefoot, but then I saw he was wearing flip-flops. He went up the staircase, then moved along the wall toward the .50 caliber emplacement, stopping where the dead soldier hung by his foot, reaching down and grabbing one end of the ammo belt and pulling it up to himself hand over hand. He managed to tug it free of the corpse, got it yoked over his own neck, and moved off toward the machine gun. He’ll never reach it, I thought, and it occurred to me that if I made it to see the sunrise, I’d get that reassignment I’d been wanting. This captain was about to end up like my last.

But he did reach the gunner. He unloaded the belt of ammo, and then went jogging back along the catwalk, never once crouching—he might have been warming up for his morning run. He came back down the stairway, disappeared behind a wall of sandbags, then reemerged with another belt of bullets and a box of 240 ammo in either hand. He headed back toward the wall.

“You got to be fist-fucking me,” I heard myself mumble.

I watched him run the ammunition up to the next gun emplacement, then come back down for more.

He did this three times in all. It was some real action-movie shit. Except it wasn’t happening in a movie; it was happening in my life. The guns got back up, our mortar crews began returning fire, and soon the enemy broke off their attack. American gunships appeared on the horizon. It was almost dark now, and I was still kneeling there in the sand of the horseshoe pit. Men were talking, lighting cigarettes. Medics from the airborne company began to see to their casualties. A few others removed the soldier dangling from the wall.

I got to my feet. It was cold with the sun down, and the skin on my forearms prickled with goose bumps. I stumbled off toward my trailer, my shirt drenched in sweat, the crotch of my pants soaked in urine.

Two days later, I was asleep in my rack when I woke to a hammering on my room’s plywood door. I opened it and found Captain Wynne standing there. He wore jeans and a T-shirt, his black Kevlar vest, the Yankees cap turned backward on his head.

“I’m going to need you,” he said.

I pulled on a pair of cammies and trailed him out into the twilight. We’d done a raid that morning and a second that afternoon. Once we’d arrived back at the OP, I’d gone to my trailer and passed out. I had the sensation I was still dreaming, and I knuckled the cobwebs out of my eyes and bit my bottom lip. I followed the captain across the compound and then up the sandbag stairway that led to the catwalk atop the walls. There was a platform there that looked out onto the countryside below us. Since the mortar attack, the tension at Roma was tight as a snare drum, and when we didn’t have a mission, we posted our weapons sergeants up as snipers. But the rest of the team had gone back out on patrol; Wynne and I were the only Underchildren left in camp.

We proned out on the plywood perch. A bolt-action rifle sat there on its bipod, a Bushnell spotting scope just to its side. I started to get behind the telescope, but Wynne motioned me toward the rifle. I’d been through the army’s sniper school, though I hadn’t mentioned this to the captain. At the time it didn’t occur to me to wonder how he knew.

I mounted the rifle, pulled the stock to my shoulder, and scoped the supply route to the north. It didn’t take long to spot the problem. About 300 out, there was a hajji walking beside the road, carrying a burlap bag and a shovel. Around Fallujah, this screamed bad guy, someone out planting IEDs. And even worse, he wasn’t alone. A girl of maybe six or seven walked just in front of him, a beautiful little girl in a brown, flowered dress, her dark hair pulled back in a perfect ponytail, too young yet to wear the hijab. She was positioned very deliberately between this man who was likely her father and the American outpost. Whenever she would stray to the left or right, the man would place his hand on her shoulder and steer her back into place.

A swell of rage and revulsion rose up inside me, and I lost my breath a few moments. It’d been happening more and more of late.

Wynne lay there next to me, staring out through the spotting scope.

“You got a light crosswind,” he told me. “South-southeast.”

I pulled away from the rifle, and turned to look at him, partly in disbelief, partly in disgust.

“There’s a girl in the way,” I told him, as if he couldn’t see.

“And he’s an asshole for that,” said Wynne. “But he’s planting bombs, sergeant. ROE says we can take him.”

“No way,” I said. “I’m not going to miss and hit a kid.”

“Don’t miss,” he told me.

I said there wasn’t any danger of my missing because I wasn’t risking the shot.

I’d yet to call him “sir.” His eye was still to the scope. Then he turned and looked at me. I thought he was about to issue an order, and I planned on telling him to go straight to hell.

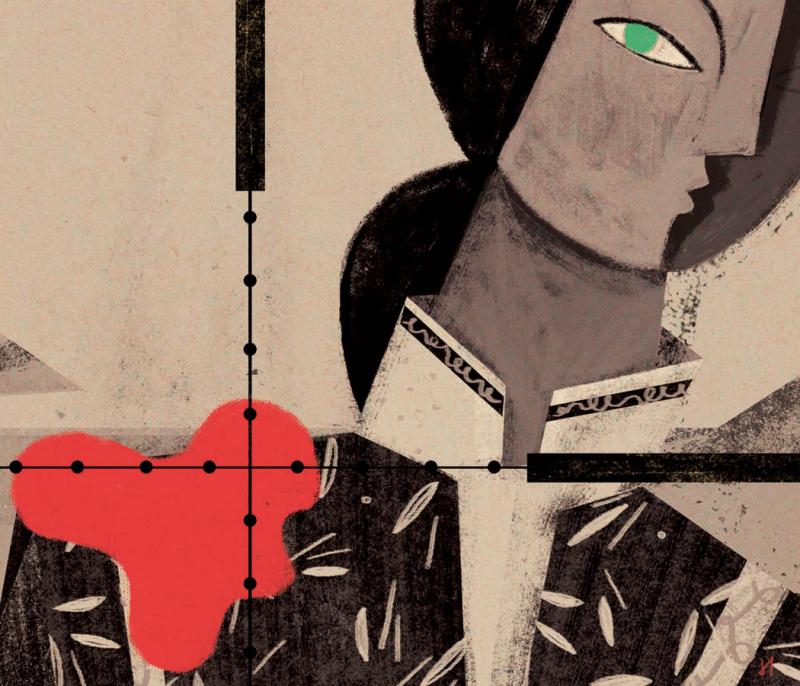

But that wasn’t what happened. His blue eyes caught the last of the day’s light. He rose, dusted his pants, and motioned for me to get up. I stood, stepped aside, and watched as he mounted the rifle. That panic went off at the base of my skull. I dropped down behind the spotting scope, and acquired the man and the girl. They were still walking. The girl, I saw, was tall for her age, the man fairly short. In sniper school, our instructors had preached the center-mass hold—meaning, you aim for the middle of your target’s torso. A lot of people think the human heart is on the left side of the chest, but it’s actually in the center, right behind the sternum. With the girl positioned how she was, Wynne wasn’t going to get a center-mass hold. He’d have to aim for a headshot. Not impossible at 250 meters, but I didn’t know what kind of marksman he was. I didn’t know what kind of anything he was. I was getting ready to find out.

He’d already started his breathing. When he got to the bottom of his breath, he’d place the pad of his index finger on the trigger and press it softly to the rear. It was too late to try to talk him out of it; any stress I added to the equation might make him drop the shot. At best, I could be as quiet as possible, give him the wind direction if it changed or kicked up, help him correct, and talk him on target if he missed. His heels were down, his hips flat on the deck. I could hear his breath going slowly in and out. I studied the Iraqi man through my scope. I studied the girl. They walked along in the dusk, and then he placed his hand on her back and they stopped. I heard Wynne exhale a final breath, get on a good empty lung, his index finger starting that slow, steady press. The entire world seemed to pause for a moment. In my right eye, a man and his child were magnified. On the inside of my left eyelid my mind projected, for the thousandth time, the windshield of a Humvee, a dirt road scrolling toward it, then a sudden detonation and the earth leaping around us on all sides.

Wynne squeezed the trigger, and the rifle bucked, and I watched as the girl’s right arm whipped behind her. The man went backward as though he’d been kicked, and then lay there on the ground, a red stain blossoming on the front of his shirt. His leg twitched once, twice, then went still. The captain worked the bolt, ejected the spent cartridge, and chambered another round. He’d shot the man through the girl, and I knew he’d done it on purpose: He’d seen an opportunity to engage the threat and he’d taken it, human shield be damned. The girl was now sitting in the road with a stunned look on her face, her mangled arm hanging limply from her shoulder. Wynne was already radioing for the medics to pick her up. He scoped the road slowly back and forth. Then he thumbed the safety and stood.

“All right,” he told me, “you can go back to sleep.”

Except, of course, I couldn’t. Not that night, or the night after, or the night after that. I lay there in my rack, trying to turn off my thoughts. I kept seeing that tiny, vanishing arm. The girl would never use it again: The surgeons at Camp Fallujah removed it at the shoulder. Thoughts like these would’ve kept anyone awake. But what really kept me up weren’t exactly thoughts.

I lay there listening to the air conditioner churning on the other side of the wall. In the distance, the intermittent sounds of the mortar crew came across camp, the thump of rounds leaving the cannon. This thing had begun to well up inside me. I couldn’t account for it. I didn’t want it to have a name. I had lain beside a captain I hardly knew and watched as he engaged a hostile through a human shield. Engage. I’d watched him send a 150-grain, Nosler-tipped bullet into the body of a child. The objective didn’t matter. Rules of engagement didn’t matter. Not to me they didn’t. Yes, he was within the bounds of procedure, and yes, you could argue, he’d probably saved lives. Maybe even mine. I should’ve hated him for it.

But I didn’t. And that’s what had me sleepless, stumbling through my days. My intellect was repulsed by what he’d done. Ethically speaking, I despised him. My emotions, however—those feelings I’d once been able to toggle on and off—rebelled against my principles: They didn’t seem to give a fuck about right and wrong. They knew this man would protect me; they knew there was nothing he wouldn’t do to accomplish it. And that thing I felt welling up inside me, I feared the name of it was love.

We stopped going into Fallujah that summer. Command had declared victory in May, but soon as the marines pulled out, the insurgents swarmed in like locusts. By November, intelligence estimated their numbers at 4,000. And these weren’t your weekend jihadis, sprinting through alleyways with ski masks and borrowed Kalashnikovs. These were men who’d spent the better part of a year sparring with American forces. Sharpshooters from Syria. Bomb makers from Chechnya. If your idea of a holiday was spilling the blood of the infidel, Fallujah was like a Sandals resort for assholes.

Our team didn’t get involved at first. We were still out roaming the countryside, kicking in the doors of sandstone compounds, winning the war one flex-cuffed Iraqi at a time. The Marines formed up outside the city on November 7, and by the sixteenth they were already mopping up: I recall the phrase “pockets of resistance” in one of our mission briefings. I figured we’d miss out on the party entirely, some of the most intense urban warfare Americans had seen since Hué City. Sounded to me like an excellent place to get killed.

Then some scout snipers got boxed up in one of the few buildings we’d left standing, and our team was ordered to go in and escort them out. We were given a set of GPS coordinates and two Black Hawks. We geared up, boarded the choppers, and off we went.

It was late afternoon when we put down. The helos dropped us off a few klicks outside the city, then got back in the air. Helicopter pilots didn’t like to wait around.

I can’t remember much about our infil that day. The sun was shifting toward evening, and the thirteen of us went along a goat path through the rubble: skeletons of houses, crumbled mud walls. It would have looked like the set of a Western if not for the plastic everywhere—plastic bottles and plastic garbage bags, and those yoked plastic rings that hold six-packs together. We jogged along a street and then turned down a wide, paved avenue where houses stood untouched to either side of us: no bullet holes in the walls or caved-in roofs. The strange thing, though, was the quiet. The power had been knocked out, and the windows of the houses were like cavernous black eyes. I hunkered into myself, anticipating the rifle shot that would put me out of my misery.

That shot never came. We reached the building where the marines were holed up, squatted in an alleyway, and waited while Wynne got on the radio and told them to come out. In a few minutes, a rusted steel door popped open, and here they came. We hadn’t seen any bad guys, but one of the marines let us know if we’d gotten there fifteen minutes earlier, we’d have seen plenty.

We’d managed to reach our objective without firing a shot, and we got back to our rendezvous point the same way. I remember thinking you didn’t need Special Forces for this kind of mission: A half-dozen mall cops could’ve done the same job. We posted up, radioed for our Black Hawks, and, when they put down, got everyone on board and strapped in. We took off and headed toward OP Roma.

The captain was seated there beside me. I turned to him and shrugged, a gesture suggesting, We should do all our missions like this.

I always kept two or three cherry Dum Dums in a pocket on my chest rig. I pulled one out, unwrapped it, and worked the hard little sphere between my cheek and gum. I leaned back and rested my head against the seat, allowed myself to finally relax.

And that’s when everything went promptly to hell.

The machine gun that strafed our helicopter stitched a seam of dime-sized holes in the fuselage and the cabin erupted in a bright spray of sparks. The air smelled like MIG welding, that scent of burning iron. Sheldon was killed instantly; his body slumped forward in its restraints. The door gunner took a round through both legs, and the copilot was grazed by shrapnel. One of the crew members seated across from me was holding his arm over his head, trying to get his mutilated hand above heart level, several of his fingers dangling by skin. The chopper wobbled, and there was a knocking sound you could hear over the roar of the rotors, and the pilot came over the radio and told us he was putting down. I glanced back at Wynne, and that’s when I saw a hole the size of my thumb over his right breast pocket, pumping blood in time with his heart.

Then we were on the ground. The other Black Hawk continued on to OP Roma, and our pilot radioed for another bird to pick us up. We set up a casualty collection point, and the helo’s crew medic—his name tape read JOHNSTON—started to perform triage. I was supposed to be helping with this, but instead I just knelt beside the captain. Birds were calling from a stand of olive trees. The sky in the west was this brilliant shade of purple. It would’ve been a gorgeous evening except for the row of American bodies lined out in front of us. I had the strange sensation of watching myself from above. I felt something separate inside me and go trailing off. The taste of copper in my mouth was overpowering, and I made myself focus on Wynne. His eyelids were starting to flutter. I spoke to him, trying to keep him with me, though I can’t remember what it was I said. The bullet that struck him had somehow missed the trauma plate in his body armor, entering behind his shoulder blade and exiting above his right nipple. It’d punched through the Kevlar like the vest was made of cotton. I didn’t know about the caliber or whether or not it’d been jacketed. What I mainly knew was that I was about to lose another captain, one I’d come to believe could keep me safe. I started through the checklist—restore the breathing, stop the bleeding, protect the wound, treat for shock—then I tossed the checklist and gripped his face in my palms. His eyes had rolled back in his head. He no longer had a pulse.

I pinched the captain’s nostrils shut, put my lips to his, and started performing CPR. This man I knelt over, a man who’d blown the arm off a little girl to smoke a bad guy, I wasn’t going to let him go. If you were to say I’d gone a little crazy, I can only say that you’re right. Maybe the real injury from the IED blast hadn’t been my hearing.

I felt a hand on my shoulder. I turned to look and saw Johnston, the crew medic. His lips were tight, and he shook his head.

“Sergeant,” he said, “I think that he’s gone.”

I stared up at him. All my life, I’d been sensible. Practical. In the drunk group of friends walking home from a bar, I was the guy trying to talk everyone out of hopping the chain-link fence of the public swimming pool, skinny-dipping in the dark. Johnston’s hand on my shoulder summoned that man. It was time he started listening.

Johnston gave my shoulder a squeeze, and he nodded. His face was very compassionate, very kind.

“Fuck yourself,” I told him, and slapped away his arm. I decided I didn’t give a shit about reason anymore. All I cared about was Wynne.

Then Johnston was kneeling there beside me. The look of sympathy on his face, his eyebrows knitted in concern, sent a tremor of rage through my body. I decided if he so much as touched the captain, I’d kill him.

“Sergeant,” he said again in a soft, respectful voice, “we have casualties. We have men we can actually save.”

“Go save them,” I said, placing the heel of one hand against Wynne’s sternum and starting to pump. In the medical course, they’d taught us to perform chest compressions in time to the Bee Gees “Stayin’ Alive,” which, oddly enough, had the exact tempo of a healthy human heart. All Johnston was doing was messing up my rhythm.

I bent down to breath into Wynne’s mouth, but this time, Johnston grabbed me.

“Hey,” he said, trying to snap me out of whatever state I was in, “he’s gone, sergeant. These others ain’t. I need your help.”

We knelt there beside the captain’s body.

The scent of feces was very strong, the scent of urine. Wynne’s bowels and bladder had given way. I raised my hands as if I’d come to myself, as though I was capitulating. Then I drove my left elbow into the bridge of Johnston’s nose. Blood burst from his nostrils, and he fell back clutching his face. I paid him no attention. I was already blowing into the captain’s mouth.

The next thing I remember was a forearm under my chin. Johnston had come up behind me, snaked his arm around my neck, and secured a choke hold. Even conventional army medics received combatives training, but they didn’t receive as much as those in SF. I turned in the direction of the choke, broke his grip, and swept him, put him on his back, mounted him, and, straddling his chest, started to pound him unconscious. By then my fellow team members saw what was happening, and they came running up and pulled me off. They must have thought I’d gone completely batshit, screaming for them to let me go, telling them I’d cut out their fucking hearts.

Then the helo pilot came walking up. HARTLEY, his name tape read. Tall and thin, bald as an egg. He was a major and carried himself like one, that cool authority of an officer forever stuck between captain and colonel. He stood for a moment watching the men restrain me like I was some mental patient. Then he asked what in fuck’s name was going on.

Johnston had managed, by this point, to make it to his feet. He saw the major standing there and tried to straighten his posture. There was blood coming from his split lip, from his nostrils, from a gash above his left eyebrow. His eyes were full of hate.

“Sir,” he said, gesturing to Wynne, “he’s trying to treat a dead man. We’ve got soldiers here who—”

“He’s not dead!” I screamed. For all I know, I’d begun frothing at the mouth.

Major Hartley snapped me a look, but pity seeped into his face. I didn’t want it. If I’d had my hands free, I might have unholstered my sidearm and shot him dead.

“Your captain—” he began.

“He’s not dead,” I repeated. Then I repeated the words again. I couldn’t stop. They seemed to be the only three in my vocabulary.

“Sir,” Johnston interjected, “he ain’t even got a pulse.”

The major looked from one of us to the other. His features hardened. He glanced over at the line of men awaiting treatment, some of whom would likely be dead within the hour, then stepped over to Wynne and took a knee beside his body. He placed his index and middle fingers to one side of the captain’s neck, and bowed his head. Like a faith healer. Or a priest administering rights. He removed his fingers, bent over, and laid an ear to Wynne’s chest. After several moments, he looked at me and shook his head, mouth tightened into a flat line.

I felt dizzy. I felt everything falling away.

Major Hartley parted his lips to address me, some words of consolation beginning to form. He turned a last time to look at Wynne, placing a thumb and middle finger on his eyelids to brush them shut.

“Sergeant,” he told me, “it’s time—”

Which is when the captain’s eyes sprang back open. Which is when he spat into the major’s astonished face.

He was in the infirmary at Camp Liberty until the middle of December. The following spring he’d be back in the field—Afghanistan this time, Nuristan Province—chasing the Talibs from their caves.

I didn’t know this when I made the forty-mile trip to Baghdad. He’d only been in the hospital a few weeks, and I guess I expected to see a sedated convalescent, a limp form surrounded by monitors, festooned with tubes. But when I parted the curtain, he was sitting up in bed reading his duct-taped copy of Ulysses, freshly shaved, his blond hair combed neatly to the side, eyes as clear and alert as a falcon’s. He didn’t look like someone back from the dead. He looked like he’d been on vacation.

There was an aluminum chair leaning against the wall. I unfolded it, dragged it to his bedside, and took a seat. If it wasn’t for the bandage poking out the top of his hospital gown, you’d never have guessed he’d been wounded at all. An IV hung from its pole there beside him: one bag of saline and glucose solution, another an antibiotic—Levaquin, I think. I could tell from his pupils he’d stopped receiving pain meds. There was no dilation. No fog in the cornea.

Those bright blue irises studied me a moment.

“Joel,” he said, as if I’d walked into a bar and found him seated on a stool at the counter, drinking beer and passing pretzels.

I sat for several seconds. Then I broke out laughing. If it surprised him, it surprised me even more.

“Lazarus,” I said, “come the fuck forth.”

He nodded at me and smiled.

“The hell else was I going to do,” he said, shrugging.

I shook my head, chuckled again, and then the room seemed suddenly to tilt, and I began weeping, my breath coming to me in great sucking sobs.

I couldn’t tell you what was happening. I hadn’t wept for Captain Pollock. I hadn’t wept for Ratchet-man or Pearson. I hadn’t even wept for Camden who I’d dragged from our smoking Humvee only to have him blow his last breaths in my face. I tried to get ahold of myself. I didn’t want to cry in front of the captain, but it occurred to me I might never be able to stop. I saw myself in the offices of the base psychiatrist. I saw myself being discharged as a Section 8. They didn’t call it that anymore. These days they handled those matters under the AR 635-200 provision. Active Duty Enlisted Administrative Separations. It meant the same thing, though: crazy. I was sobbing hysterically while having this very technical conversation in my head about army regulations regarding the discharge of the mentally unstable. Yet another sign I’d gone nuts.

And who was I weeping for anyway? Captain Pollock? My dead team? I had the strange sensation I was weeping for myself, or the self I once had been, but I couldn’t do the math on any of that. The calculus of everything was suddenly beyond me, and I held my face in my hands and balled like some widow. Whatever you do, I told myself, do not look fucking up. I thought I couldn’t bear to see the expression on the captain’s face, that this would’ve sent me right over the edge.

I felt a pair of hands gripping my forearms. I assumed a nurse had walked in, maybe to lead me down the hallway to a padded cell. Be the best thing for everybody, I remember thinking.

I opened my eyes and stared out through the screen of my fingers. Wynne was kneeling there in front of me in his thin hospital gown, his IV line stretched between its stand and the catheter in his arm, kinked several times like a garden hose. The crying stopped as though someone had twisted shut a valve. That quickly, that precisely. The captain’s palms rested on my forearms. If he’d pulled out an engagement band and slipped it on my finger, I wouldn’t have been any more surprised. Or grateful. And I knew in this instant that whatever horror awaited us, the two of us would be walking into it together. And I knew, also, we’d come out the other side—stronger, stranger. It hadn’t worked out that way for Sheldon, but I knew it would for me. It wasn’t something I could account for: I had to take it on faith. And I believed it, just like I believed the next breath I drew would siphon air into my lungs. Like I believed the war we fought would go on forever. That the man I’d always been had died right there.