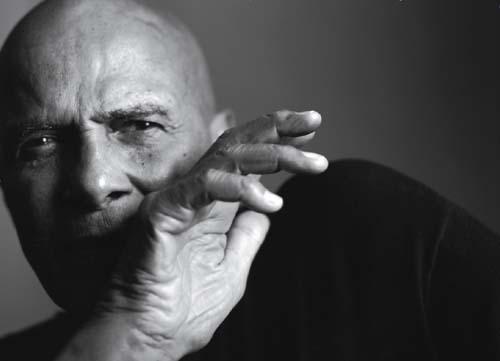

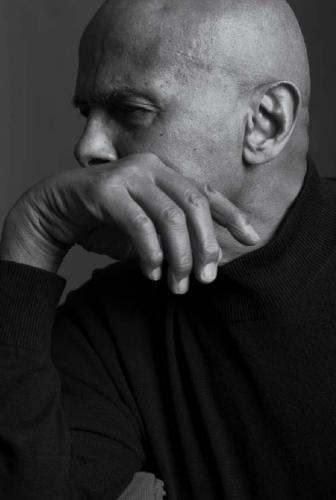

Once, more than half a century ago, he was the handsomest man in the world. A radiant man. It was a matter of bearing, of voice and gesture and timing. He had that high, buttery baritone, nothing special really, except, he says, “I knew how to use it”; and that smile, the genuine pleasure that seemed to roll off the so-called King of Calypso in soft little waves; and those eyes, bedroom eyes but darker, almost cadaverous but alert, ready. The eyes revealed the simmer inside. “This hard core of hostility,” a director once said, comparing him to Marlon Brando. That mesmerizing anger. “He’s loaded with it.”

And now? In a diner he asks a kid in a ball cap where he’s going to college. Kid raises his brim and squints up at him—who are you? At a museum he tries to chat up a guard from Jamaica, where down by the docks he learned to sing as a boy. The guard murmurs and smiles. Old man, the guard says with his eyes.

One day we’re walking up Broadway with his wife, Pam. She admires a Porsche, antique and teal. “What year do you think it is?” she asks. Sixty years old, nearly a quarter century his junior, she’s his youthful bride. He walks over to the car’s owner: rumpled and pasty, wearing shorts and an Izod, plugging coins into a meter.

The old man takes out his money roll. It’s fat and bound by a gold clasp. “How much?” he rasps. His voice sounds familiar but scraped down, sharp pebbles beneath sand.

The owner looks at this stranger, his skin the color of dark honey, with a half smile of alarm. “Uh …”

The old man grins, a shining, slightly crooked expression. It’s like a light turning on; you can almost hear the pasty man think, Wait—you’re still alive?

“How. Much.”

The pasty man twitches, excited now. “One hundred thousand dollars?” he says, just in case Harry Belafonte—it’s Harry Belafonte!—isn’t joking. Belafonte pats his shoulder and moves on, keeping time with his carved wooden cane. “I’m going to tell my wife you tried to buy my car!” the pasty man chirps after him.

One day Belafonte says, “I’m taking you to a movie.” There’s a recent documentary about his life called Sing Your Song, a brightly inspiring companion to his 2011 memoir My Song (written with Michael Shnayerson). They’re both elegant testimonies, both surprisingly candid, and yet neither quite bridges the peculiar gap between Belafonte’s past, when he was labeled “subversive” and spied on by the FBI, and his present: a nice old man who used to sing folk songs with a Jamaican accent, a “national treasure.” “Our heritage.” How did that happen? To him? To us?

“I’ve seen Sing Your Song,” I tell him.

“That’s not the movie,” he says. He won’t tell me its name. He and Pam and I pile into a cab and shoot downtown to a theater on West 23rd. Invitation only: the families of the movie’s stars, there for a special screening of a documentary, Zero Percent, about a prison-college program at Sing Sing called Hudson Link. The program’s director, Sean Pica, is waiting. “Mr. B!” Pica says, bouncing on his toes. Pica is a graduate himself. He earned his high school, college, and master’s degrees inside. “I grew up in the town of Sing Sing,” he likes to say. That’s where he learned about Harry Belafonte. “I’ll tell you about Mr. B,” he says. At Sing Sing, five times a day, every man’s in his cell for a head count. One man missing, the whole prison shuts down. Belafonte’s there one afternoon to meet about thirty inmate-students. The superintendent has turned over his conference room for the gathering. All he asks is that he be allowed to sit in. “Huge Mr. B fan.”

Almost 4 p.m. Head count approaching. “Gotta wrap up,” the deputy of security tells Belafonte. “Gotta get these men back to their cells.”

Belafonte waits a beat before giving the deputy the smile.

“We’ll take another fifteen minutes,” he says.

“But—” goes the deputy.

“We will take another fifteen minutes.”

And that’s how it happens: 4 p.m., no count—not at Belafonte’s table, not anywhere in the prison. Pica couldn’t remember anything like it. “I love Mr. B,” he says. “He’s the guy who stopped the clock.”

Don’t get stuck on the bananas. You know the bananas. Day-o! Day-o-o-o. Come Mr. Tally Man, tally me banana. “The Banana Boat Song” was the hit that made Calypso, Belafonte’s third album, the first LP in history to sell a million copies—1956, the same year a white boy from Mississippi released a record called Elvis Presley. Belafonte outsold Elvis. This fact is important to him. Even now, eighty-four years old, his left eye wandering, his right hand curled around the head of his walking stick, his still-great frame folded into the front row of a film archive’s darkened screening room, just us and Pam this time.

Belafonte was first. First black man to win a Tony; one of the first to star in an all-black Hollywood hit (Carmen Jones, 1954); first to star in a noir (Odds Against Tomorrow, 1959—“best heist-gone-wrong movie ever made,” says James Ellroy); first to turn down starring roles (To Sir, With Love ; Lilies of the Field ; Porgy and Bess ; Shaft) because, he said, he’d play no part that put a black man on his knees or made of him a cartoon. We’re here in this screening room to watch a forgotten hour of television for which he won the first Emmy awarded to a black man for production, for being in charge.

When I found the show in the archive, I thought it would be more of what I believed I already knew about Belafonte. The albums I’d bought were labeled “easy listening” or “folk,” as in harmonizing trios who wore matching sweaters. Then I watched. My eyes went wide. I started shaking my head in disbelief. I think I gasped. I was wearing the archive’s cheap headphones, sitting at a monitor in a dark room. Other researchers hunched over screens, all our faces flickering blue. I laughed. I slapped the desk. My eyes watered. Goddamn. I felt like I was watching a different past, one in which the revolution had been televised. Goddamn. As if that was what TV was for. A signal. This, I thought, this.

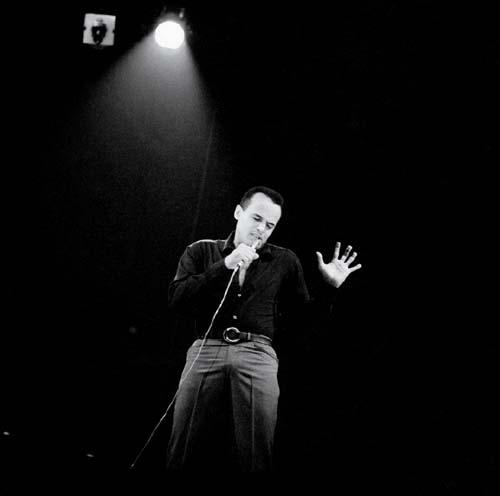

December 10, 1959, 8:30 p.m., live. Kids across America are groaning because the night’s entertainment, Zane Grey Theatre, white men with six-guns, has been displaced by, of all things, Revlon. Makeup. Miss Barbara Britton, the sponsor’s hostess in ball gown and pearls and white gloves up to her elbows amidst crystal cases of Christmas possibilities, introducing “the exciting Mr. Belafonte,” the dreamiest and safest Negro in America, sweet as Nat King Cole and so much prettier.

At least part of that was true. “From the top of his head right down that white shirt, he’s the most beautiful man I ever set eyes on,” said Diahann Carroll, who costarred in Carmen Jones. His beauty was like a kindness, golden, encompassing. He’d outsold Elvis by offering a gentler thrust. Elvis stood center stage and pushed. Belafonte, a bigger man—six-two, 185 pounds—curled his shoulders around his Cadillac chest and seemed to be promising the spotlight to Miss Barbara Britton, to Mrs. America, to the married white womanhood of the nation, if she could gather the courage to come up on stage and join him. An offer, not a proposition.

But that’s not what made him a star. It was this: Elvis was going to seduce you. No, that’s a euphemism. Elvis, legs jittering, wanted to fuck. Belafonte, fingers snapping, seemed like he’d be seduced by you, and then you’d make love.

That pisses him off, even now. “People saying it in line,” he rasps, sweetening his voice to mimic the white women who presumed he was some Mandingo for the taking: “ ‘I’ll tell my husband, ‘I’ll leave you in a minute, he’ ”—Belafonte—“ ‘can put his shoes under my bed anytime.’ Never stopping to debate whether I would like to do that.” He was a sex symbol, he got that. But what kind? A man or a “boy”? Lover or servant?

Tonight with Belafonte opens: a harsh charcoal drawing of a man so twisted, so fixed in nothing but pain, that he’s barely recognizable. Belafonte. The music begins. Ca-chink. A beat. Ca-chink. A beat. Not a drum but a tool, like metal striking stone. Ca-chink. Ca-chink. Eleven times the hammer falls, and then the light comes up, a spot on Belafonte. “Voice and hammer, that’s it,” the old man murmurs now, watching himself then. Behind him, seven bare-armed black men, biceps like cannonballs, faces in shadow, let their hammers fall, shoulders heaving. Their chains hang from the darkness above, huge heavy links like anchors. Belafonte’s center stage, his signature outfit—high, tight mohair pants, a sailor’s double-loop belt buckle, a tailored shirt of Indian cotton open almost to his navel—made over into a prisoner’s rags. His right hand is a claw, his left is a fist, his eyes are blackness and his legs are wide, his feet planted. He begins to sing. A hard dragging snarl. I don’t want no bald-headed woman, she too mean lord-lordy, she too mean …

“Bald-headed woman,” Belafonte snickers now, in the screening room. “Perfect for the product. Revlon.” He snorts.

It’s a chain-gang song. Belafonte had found it ten years earlier, and he had been waiting to sing it ever since. He found the song on a record nobody listened to back then, a chain gang recorded live. Found it in the Library of Congress, flat-broke Harry bumming his way down to Washington to sit in a room with big black headphones framing his temper, soaking up songs that made more sense to him than the pop on the radio. “Folk music,” with its echoes of coffeehouses and college boys, doesn’t convey what Belafonte heard, unless you cut away the dull virtue that’s come to pad the term folk, cut it down to the gristle.

I don’t want no sugar in my coffee,

make me mean, lord-lordy,

make me mean.

There’s a twitch in his narrow hips. The hammers behind him swing. “How simple,” he murmurs now. “How very simple.” On-screen, his hands plunge down as if grabbing on for life to something that burns.

I got a bulldog, he weigh five hundred,

in my backyard, lord-lordy,

in my backyard.

Belafonte bangs his stick on the screening room’s carpeted floor, his grin gorgeous like it’s 1959 but stripped by age, plain now as what it was then: a kind of fury.

I say, “You changed the lyric.” On the original recording, it’s “jet-black woman.”

Belafonte looks at me like I’m a fool. “I changed lyrics on everything. Like that thing upstairs?” Earlier, we’d watched a happier Harry, singing a song called “Hold ’Em Joe” on Jackie Gleason’s Cavalcade of Stars, Caribbean costume and the all-white June Taylor Dancers prancing as Belafonte leads a donkey on the stage. It made me wince. A donkey. But I wasn’t reading the code. “You know what ‘Hold ’Em Joe’ is?” He grips his stick. “It’s a phallic song. ‘My donkey’? Here I was, doing the song known by millions of people in the Caribbean as one thing, and I’m on the most popular show in America singing the same song. I made ’em think it was a song about a donkey.” He laughs. Cackles. The donkey’s a metaphor, but so is the phallus for which it stands. Metaphors all the way down, from donkey to defiance to the root, humanness. Not in the abstract but in the flesh: a body: a human being.

Belafonte nods toward the screen. “Let’s play it.”

The hanging chains tumble down and the first number ends with a close-up of Belafonte’s boot on the iron heap. But the next song’s a whisper, the guitar behind him just a little strum. Sylvie. Pause. Sylvie.

I’m so hot and dry.

Sylvie …

Sylvie …

Can’t you hear,

Can’tcha hear me cryin’?

“ ‘Sylvie,’ ” he says now. “When I heard this at the library, by Leadbelly, it was a children’s song.” Leadbelly was Huddy Ledbetter, from whose twelve-string guitar not just Belafonte but Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and dozens of others absorbed the musical truths of the ex-con Life magazine once called “Bad Nigger.” Leadbelly really had worked on a chain gang, but what Belafonte took from him wasn’t “authenticity.” His “Sylvie” doesn’t sound like Leadbelly’s; it’s slower, sadder, sharper.

Sylvie say she love me

But I believe she lie

She hasn’t been to see me

Since the last day in July.

“I made no connection with purism,” he says. “I looked at the art of it and I said, ‘Goddamn. How long has this room been here? Why didn’t I ever see this wing of the house of life?’ ”

For the rest of the show, Belafonte roams the house. Ballads and kids’ songs and comedy songs and work songs, “Jump In the Line” and “Mo Yet” and “John Henry.” Odetta’s national debut singing a version of “Waterboy” that could drive nails into the cross. The camera cuts to her in a spotlight, and the visual alone makes your breath stop, because she doesn’t look like anything you’ve seen on television. Because she’s fat. Not fat like a gospel singer, that ready role for a big-voiced big woman on TV, but too fat, beautiful but probably not healthy, angry-eat-too-much-because-you-hurt fat, and she stands on the stage in that stark spotlight in a plain A-line frock, her shadow her only accompaniment, and she plays her guitar like it’s the rock and she’s the hammer.

“God,” Belafonte says, watching it now. He remembers how he got this big, dark-skinned, angry woman on television. “Heavy voice, heavy color,” he says. It was at a meeting with the account executive for Revlon, Madison Avenue. “I got some guests,” Belafonte tells him. “And the first and most important guest is Odetta.”

The ad man waits for more. Belafonte stares. Finally the ad man blinks. “Ah, what’s an Odetta?” he says.

“Well, I don’t know,” Belafonte answers. “She looks a little bit like Paul Robeson.”

That was a name you didn’t even say out loud then, a star—Showboat, Othello, The Emperor Jones—gone radically Red. “The Russia-loving Negro baritone,” one newspaper called him.

“Uh-uh,” murmurs the ad man. He’d been thinking maybe a sultry soprano like Lena Horne. Light-skinned.

“And she sounds like him, too,” adds Belafonte, deadpan.

“Oh,” says the ad man. He’s responsible for the hour of primetime television Revlon has bought and turned over to Belafonte, who, by the way, will not be singing “The Banana Boat Song,” and has also decided that he won’t accept commercials.

“Oh my god,” says the ad man.

Belafonte grins now, and says what he thought then: “Swallow that shit, motherfucker.”

And they did. Belafonte had negotiated one of the first pay-or-play contracts in the business. He’d get paid whether they used it or not. Revlon’s money was already gone.

So Belafonte had an Odetta, and the first black dancer with Balanchine’s New York City Ballet, and two then-unknown bluesmen named Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and a young director named Norman Jewison, whom Belafonte had plucked from a dead end after Jewison had been fired—by Revlon—just weeks before. Jewison, who’d go on to become a three-time Oscar nominee, thought he had nothing left to lose; he’d already lost. That was how Belafonte liked it. Bottomed out and mad. He had a voice, a dancer, a camera, and his own almost supernatural control of the stage. What he needed, he realized, was a church. A temple. Because he wanted Miss Barbara Britton to understand what this really was. Not a song and dance—not just a song and dance—but—“you see it?” he asks me, and through his eyes, then my own, I do: A judgment. He could have built a gallows, but no—he chose a church. He built a church, right on stage. High modernist, nothing but a line, an angular arch, his singers sitting in the pews, Belafonte one among them and now Odetta rises up like the tide, singing “The Walls of Jericho,” gospel made over as fight song.

“Pause it for a minute,” Belafonte says. He’s not a believer, never was. For him it’s political. He can’t forgive the church the slave catechism taught by traders of flesh: “Your redemption lies in Heaven at the right hand of God,” he recites, his voice filled with contempt. “Never rise up against your oppressor. Don’t rebel.” But, he says, that was just the surface of the church. Beneath it, or maybe within it, were other meanings. “Bible readings, telling stories, passing information. You planned all the escapes in church. You sang your songs in code.” Nothing’s changed, he says. “Why does the code work now any different than it did then?”

Last number: He’s standing on a pillar surrounded by his singers and dancers, looking down on them like a preacher. “I’magonnatellyouboutthecomingofthejudgement!” And then he comes down into the crowd and gathers them up and wheels them around to a ramp rising from the stage—“There’s a better day a-coming,” he sings, the jazz inflection speaking the grief of the days behind—marching up the ramp, a blues stomp, the camera rising and dipping, almost all one shot, Belafonte first leading the crowd then overwhelmed by it, a mass of men and women of all races growing to fill the screen, singing the old gospel like it’s the new power, here and now, this world and not the next.

Did you see that fork of lightning?

Fare ye well, fare ye well!

Can you hear that rumbling thunder?

Fare ye well, fare ye well!

Then you see them stars a-falling!

Then you see the world on fire!

Cut to the chandelier of the Revlon room, white couples in tuxedos and gowns, the evening’s hostess in pearls. “Well!” says Miss Barbara Britton. “Have you ever heard anything like it before?”

In 1959, Belafonte was playing Vegas for $50,000 a week. Every night he looked out on an ocean of white. Black people couldn’t have afforded his show even if Vegas hadn’t been segregated. But TV? Black folks had TVs. One night on television reached more black people than a year of Sundays at the Apollo. TV, Belafonte thought, would be his hammer. He’d use the idiot box to break chains. Revlon ordered another five specials.

But after just one more show, Charlie Revson, scion of Revlon, had a problem. “The white guys down in the South don’t want it,” he said. “They’ll black out the station.” It was the backup singers, the dancers, he said. Some black, some white. Choose, said Revson. Didn’t matter which—so long as they were all the same. He figured Belafonte would probably prefer the color, but really, Revlon wanted to respect his freedom. You’re the artist, Mr. Belafonte. So choose. Black or white.

Over a series of conversations between us, out on the street and up in his apartment, in a taxi and in a diner booth, here in this screening room, Belafonte will retell this story to me. It’s one of the moments to which he returns. “I said, ‘See you around, and goodbye forever.’ ” He smiles when he says this, that shark-toothed generosity of a smile. “See you around,” the words by which he set himself free.

“Instead of being a grateful nigger, walking in and saying, ‘How wonderful you gave me this,’ I’m sitting there saying, ‘No. See you around.’ ”

He still got paid. Pay-or-play: A check from Revlon for $800,000 showed up at his office that afternoon, the price of keeping America’s biggest black star off TV.

“Fear and consequences,” says Belafonte. He pushes himself up and eases out of the screening room like he’s carrying the cane just for fashion, one hand brushing the wall along the archive’s dark hallway.

Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. was born in New York on March 1, 1927. His father was the son of a black Jamaican mother and a white Dutch Jew, and his mother, Millie, was the daughter of a black Jamaican father and a white mother. They were both illegal immigrants. They kept no family pictures; Millie feared they might serve as evidence. Of what? Hard to say. Proof of their island past? Every so often she changed their family name. Just a letter here, a letter there, enough to disappear among the files, rounding down the syllables until they became the Belafontes.

His father, Harry Sr., cooked on the banana boats that sailed between New York and the Caribbean. Millie worked as a maid. She was stern and Jamaican-proud, raised on a black island with a history of revolt. Harry would stand beside her among hundreds of other black women dressed in their Sunday best every day, beneath the stone arches up past 97th Street, where the train tracks come up from underground. White women would inspect black women, pick the day’s help. Sometimes a white woman would let him follow his mother into the backseat of a giant automobile. One Saturday evening in a kitchen on Central Park West one of those white women slapped Millie, for what he can’t remember. Just the sound and her response: She went for a knife. His aunt, working that night, too, had to hold Millie back.

Sundays after Mass, Millie would take him to the Apollo to hear Count Basie or Billie Holiday or Ella Fitzgerald. On the street he’d see Duke Ellington, Langston Hughes. But his heroes were gangsters. White ones, because that’s who was on the screen: James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson. Millie worried. Seven years old and her boy already knew how to swagger, how to curse and fight dirty. Ran from a white boy just once, to keep his shirt clean for the school play, and even then, he went back. “To stomp the guy.” Millie could read the odds. She put him on a banana boat, sent him to his grandmother. White-skinned and blue-eyed, she lived in a house on stilts in the country, surrounded by plantains, mangos, and yams. “I was a great night gazer,” he’d recall. “I used to climb up in a mango tree and lie back and eat mangoes and look through the leaves at the sky.”

He rode the banana boats back and forth between Harlem and Jamaica for the next two years. Jamaica saved him. “Black people saw people from Jamaica as the Jews of the black world,” he says. They were educated; they pushed. “You look at us, Malcolm X and his island roots, Sidney Poitier and his island roots. Look at Stokely Carmichael, ‘Black Power’ coming from his Trinidadian mouth.” On the docks, from banana loaders and fishmongers, he learned to sing mento, the Jamaican music out of which reggae grew. In the streets, in Harlem, he learned to gamble. For a while he tried to pass. Sometimes he watched his mother cry. He fought, he drifted; sometimes he sang. When he was seventeen he saw a movie called Sahara, starring Humphrey Bogart. There was a Sudanese fighting beside Allied soldiers in the Libyan desert, a black man strangling a Nazi pale as the moon on that big silver screen. Yes, thought Belafonte. That was what he wanted.

He joined the Navy, where another sailor passed on a copy of W. E. B. Du Bois’s just-published Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept. Du Bois was even better than the movie. He wanted more. He raged at a white librarian who told him she could find no books by the author named in the back—“Ibid.” He swung on an officer, a white man, and went to the brig. He found other books, more Du Bois. When he returned to Harlem, he kept reading. He worked as a janitor. That’s what he’d be, he thought. A janitor who liked to read, a man with a broom, wise to the world.

One day a woman who lived in his building gave him a pair of theater tickets. The theater was called the ANT, the American Negro Theatre, and the play was called Home is the Hunter, a story of black veterans returning to Harlem. He knew these characters. He was one of them. He could play these parts. An actor, he thought—maybe that was what he could be. He used G.I. Bill money to enroll in the New School’s Dramatic Workshop. His classmates were Tony Curtis, Walter Matthau, Rod Steiger, and a young Marlon Brando. Sidney Poitier, another young West Indian actor he’d met at the ANT, was his best friend. “This bright, tough cookie who knows where jugular veins are located,” Poitier would later write of Belafonte at twenty-one.

“Sidney radiated a truly saintly calm and dignity,” Belafonte would respond. “Not me.”

He made his professional debut in 1949 at a jazz club where he would become a regular, a music obsessive who’d bring scripts to study at a dim table while jazzmen blew into the morning. The musicians took pity on him. Maybe he could sing some songs during an intermission. Al Haig, Lester Young’s pianist, volunteered to back him. When Belafonte took the stage in a secondhand blue suit, introduced as “Harry Bella Buddha,” his throat dry and his hands sweating and his mind reeling not with doubt but certainty—I don’t belong here—Charlie Parker’s bass player, Tommy Potter, slipped onstage. Then came Max Roach on drums. Parker picked up his saxophone. Bella Buddha was a nobody, and he had the best band in jazz. He sang “Pennies from Heaven.”

Belafonte knew what he brought to the combo: a handsome but untrained voice, limited range, and a preternatural sense of timing. Not musical timing, exactly; the beat and pause of a showman. “Somebody once said to me, ‘Do you consider yourself an actor or a singer?’ ” he says. “And I said, ‘By all measure I consider myself an actor. And I will tell you something else, my claim to arrogance. I think I’m the best actor in the world.’ ‘Well, that is arrogant. How do you draw that conclusion?’ ‘I’ve convinced you I’m a singer.’ ”

Belafonte knew what he brought to the combo: a handsome but untrained voice, limited range, and a preternatural sense of timing. Not musical timing, exactly; the beat and pause of a showman. “Somebody once said to me, ‘Do you consider yourself an actor or a singer?’ ” he says. “And I said, ‘By all measure I consider myself an actor. And I will tell you something else, my claim to arrogance. I think I’m the best actor in the world.’ ‘Well, that is arrogant. How do you draw that conclusion?’ ‘I’ve convinced you I’m a singer.’ ”

The papers started calling him the “Cinderella Gentleman.” He bought new clothes, he crooned, he cut records. Brando envied him. Henry Fonda followed him from gig to gig. And he had a wife now, Marguerite, and a baby daughter, and he made enough money to support them. But it felt wrong. After shows he’d go backstage, take his own measure in the mirror. He wore a tuxedo now. He sang to order. A pretty face, interchangeable with a dozen others. What he sang wasn’t jazz. It wasn’t anything. “Pop ditties,” he told himself. Music that didn’t matter.

In 1950, he took a booking in Miami. “Land of the Jews,” his manager reassured him. “The segregated South,” Belafonte responded. The club gave him a handful of passes, the paperwork necessary for a black man to move about town after curfew. “As long as I was onstage, crooning love songs, I had a certain power over them,” he’d write. “But when the lights came up, I was just another colored man hotfooting it back to Colored Town—or else.” He made up his mind that night. He was done.

He plowed his savings into a hamburger joint in the West Village called The Sage. He and his partners bought wholesale from the grocery store and fed hard-luck cases for free. As a business, The Sage was a disaster. But as a scene? Tony Scott, a clarinetist who’d played with Billie Holiday, was a regular. A cantor taught Belafonte Israeli folk songs. The Village Vanguard, where Leadbelly was playing the music Belafonte wanted to sing—“raw, gritty, American songs”—was just down the street. Sometimes, those songs were right in The Sage. “We’d just stop everything and sing right there,” Belafonte says. It was the beginning of his second act.

When Belafonte played Carnegie Hall in 1959 he opened with one of those raw American songs: “Darlin’ Cora,” about a boss who called him “boy.” His friend Pete Seeger, along with the Weavers, had opened with the song at Carnegie three years before, but they’d played it loud and fast. Seeger, a Harvard boy, had been blacklisted, disappeared from the top of the charts, and he sang the song like an assertion: I am. Belafonte’s anger was more deeply aged. He let the song simmer, backed by a trotting guitar.

I ain’t a man to be played with,

I ain’t nobody’s toy.

Been working for my pay for a long, long time …

He leans on the word and the guitar lopes into a gallop:

Well I whupped that man, Darlin’ Cora,

and he fell down where he stood

Don’t know if that was wrong, Darlin’ Cora

He stretches her name out, singing over the dead man’s body:

But lord, it sure felt good!

He always made it feel good. Strip a half century of camp off Calypsoand it’s one of the most lilting grooves recorded. It’s the music of Pax Americana: island holidays for the middle class, nightclubs for working men and women. It’s also the beginning of the end of all that, or maybe the end of the beginning of something else: The most successful African-American musician in history had made the nation hear him on his own terms, had made them love him for singing his own song. Forget the “Day-o” in your mind. Shuffle the songs, start with the “hoooo-uh” of “Dolly Dawn” or the high, falling cascade of “I Do Adore Her” or the perfect rhythm of “Man Smart (Woman Smarter).” Then go back to “Day-o” and listen to the pleasure and the edge, the code within the act.

“What I did,” Belafonte says, “what made conscious political sense, was to say, ‘Let me have you love me because I will show you my deeper humanity.’ ” He beats out the “Banana Boat” rhythm on his desk. “If you like this song so much that I can engage you into singing it, delighting in it, I’ve sold you a people, a region, a culture. If you look more deeply into that region, that culture, those people, you’ll see a lot of things that have to do with oppression, with slavery. The song is a work song. It’s a protest song.” Calypso is Trinidadian music, derived from West African kaiso by slaves who used it to mock their masters. Belafonte tilts his head back, eyes half-closed, and opens his palms, becoming a Kingston dockworker. “ ‘I want to get home. I want to drink a rum. I want to get out from under.’ ”

We’ve been talking in Belafonte’s living room for an hour when his wife, Pam, reminds him he has a phone interview about his memoir with Essence, a fashion-and-lifestyle magazine for African-American women. Belafonte puts the reporter on speaker and nods at me to listen. The interview doesn’t start well.

“Did you learn anything about yourself through the writing process?”

“Yep.” Silence.

But after a while he starts riffing on perfunctory questions, veering from entertainment to art to politics. The interviewer tries to play along.

“You wrote that Barack Obama ‘lacks a fundamental empathy with the dispossessed,’ ” she says.

“He should be sitting down where nothing but the poor reside and counsel with them and talk with them as he does talk with the bankers, and as he does talk with the money lenders, and as he does talk with the blue-collar workers or the middle class. All those places he sits, he never sits among the blacks.”

The reporter interrupts him; he continues; she interrupts again. Three times he tries. Essence wins.

“Before I let you go, this is a magazine for black women. Could you talk a little bit about what you love about black women?”

Long pause. Belafonte’s first wife was black. His second, the woman with whom he spent most of his life, was a white dancer named Julie Robinson. When Belafonte married her in 1957, the outcry was so great he wrote a cover story for Ebony magazine called “Why I Married Julie.” Even Robert F. Kennedy deemed Belafonte’s interracial love life “a sign of instability.” Black critics said he’d betrayed black women. Ebony ran a sidebar with the opinions of Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, Mahalia Jackson, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington. “We didn’t marry to prove a social point,” protested Belafonte. “We did it for love.”

More than half a century later, he’s being asked the same question. “Now,” he says, “you ask me what do I admire most about black women. What I most admire in a woman who faces oppression is her willingness to be smart and cunning in overthrowing that oppression. Other than that, black women don’t hold very much more than all women. Because—”

“I do thank you so much for your time with this,” the reporter interrupts. “Is there anything else you wanted to say?”

“Yes. We have a culture where to tell the truth is not an easy thing to do. Every day we wake up we do our minstrel act. And our minstrel act means we put on the mask. We put on our burnt cork. And we grin like we know we have to grin to get through the day even though there’s a rage inside of us.”

It sounds like the reporter is trying to break in. Like she wants to get away from this crazy old man. Like she can’t hear the confession. Because Belafonte, he corked up, too. The donkey’s a metaphor, sure, metaphors all the way down, but up top, on the surface, it’s still a donkey on a stage: an act. “Everybody does it,” he tells the reporter. “It’s the American theme.”

He pauses, and the reporter seizes her chance: “Have a terrific rest of the day!”

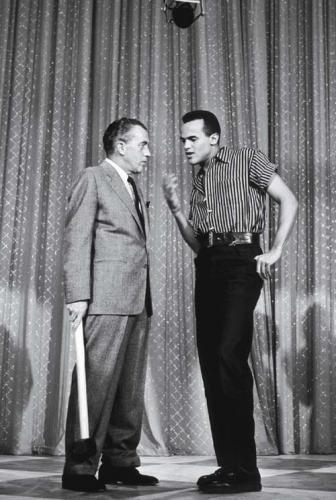

Belafonte was twenty-nine years old when he met Martin Luther King Jr. in the basement of Abyssinian Baptist in Harlem. King was twenty-seven. “He was shorter and stockier than I expected,” Belafonte writes in My Song. But then, he hadn’t expected much. “You don’t know me,” King had said when he’d called and asked for the meeting. Belafonte thought he did: just another hustler working his Bible routine. “One of the first things that I said to Martin was, ‘I gotta tell you right now, I understand your mission, I hear what you’re saying, but I gotta tell you, I’m not the church.’ ” There’s a picture of the meeting in Belafonte’s apartment. Just two men in a bare basement, New York and Georgia, a singer and a preacher, a little wooden table between them. Belafonte’s in a dark suit, hands folded, listening. King’s leaning forward. “I need your help,” he’s saying. “I have no idea where this movement is going. I’m called upon to do things I cannot do, and yet I cannot dismiss the calling.”

They spoke for three hours that day, the beginning of a relationship that would become one of the deepest in each man’s life. “There was an almost invisible electricity,” was how Sidney Poitier described the bond. “Almost mystical.” Material, too: Belafonte became one of the Civil Rights Movement’s biggest donors. “[He] took only what he needed for his family and turned the rest of the money over to King,” writes historian Steven J. Ross. Belafonte wasn’t trying to buy his way out of the struggle. “He was always trying to figure out how does this”—his fame, his fortune—“translate into building a movement,” Danny Glover told me. Belafonte funded the Freedom Riders and provided much of the backing for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the younger, more radical alternative to King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council. He was King’s liaison to the Kennedys; Bobby and Jack relished Harry’s style. He paid King’s bills and hired a secretary and a driver for Coretta, left home alone with their four children. And when King was in New York, he stayed in Belafonte’s twenty-one-room apartment, a hideout from even King’s closest allies.

“Nobody knew it was there,” Belafonte says. “Nobody knew his number. Nobody knew anything. He had his own key, he had his own bathroom, he had his own entrance.” King would slip in late, and Julie Belafonte would bring out the Harvey’s Bristol Cream they kept for him. King always marked the bottle with a line. It was a joke, or maybe it was a border between the world outside and his secret retreat at Harry’s.

Some nights they’d talk tactics and strategy, some nights it was the Kennedys and Bull Connor. Sometimes they’d just crack each other up. Who am I? one man might say, miming a pompous strut. Oh, man, that’s gotta be Abernathy, and they’d both double over in giggles. Across the hall from that photograph of King and Belafonte meeting for the first time, there’s another picture of the two of them at Harry’s, the rarest of images of King: busting a gut with laughter, eyes squeezed shut, not the noble Christ figure we’re used to now but a fat, jolly Buddha.

Some nights King wrote. He’d scratch out something on a yellow legal pad, put on his MLK suit and leave for a fundraiser, come back, write a few more words, crumple the page and toss it. “Before it hit the floor, my hand was there like Willie Mays,” says Belafonte. “ ‘Don’t throw that out! Hold on, man! That’s your writing.’ ” He’d smooth the wrinkled pages and store them away.

Being close to King meant being a target, too, death threats and bomb scares. Belafonte’s closest call came in 1964. He’d tapped Frank Sinatra, Fonda, Brando, Joan Baez, and his own funds to raise money for the Mississippi Freedom Summer’s voter-registration drive. Then three activists disappeared. On August 4, the FBI found the bodies. That night one of the leaders of the voter drive called Belafonte. Change of plans. Originally, volunteers were to work two-week shifts. Now, they were going to stay—every one of them. They needed more money.

“How much?” Belafonte asked.

“At least fifty thousand dollars,” the activist said—within three days. There was no way a black man in New York could wire $50,000 to a civil-rights activist in Mississippi. Somebody would have to hand deliver. Belafonte called Poitier: “They might think twice about killing two big niggers,” Belafonte told him. When they landed in Jackson, a handful of activists hurried them into a Cessna that took them to a dirt runway in Greenwood. As soon as they stepped off the plane, the pilot wheeled around and took off. Belafonte remembers a single light bulb dangling over a gate to the dirt road beyond; Poitier believes there may have been two. When they got into the car, a pair of headlights across the field popped on.

“Federal agents,” Belafonte told Poitier.

“Agents my ass,” said their driver. “That’s the Klan.” The driver, a man named Willie Blue, made straight for the lights. At the last second he veered off. “Faster, man!” shouted Belafonte. Uh-uh, said Willie Blue. Deputy would pull them over and they’d wind up just like the three boys the feds pulled out of the river. The car jolted when the truck behind them began ramming. It’s okay, said Willie Blue. As long as they could stay in front, the men in the truck couldn’t draw a bead.

Close to town, a convoy came out to meet them. Hundreds of activists, white and black, were waiting in a dance hall. The applause, remembers Belafonte, was like nothing he’d ever known. He let the crowd fall quiet. Just Mississippi night. Then he sang.

Day-o! Day-o-o-o!

He changed the words.

Freedom, freedom, freedom come an’ it won’t be long.

When the song was over, Belafonte held up a black doctor’s bag and dumped $70,000 in small bills on a table.

The loveliest image of Belafonte I’ve seen is in a CBS News broadcast of the 1965 march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, original capital of the old Confederacy. The third march. The first, March 7, 1965, “Bloody Sunday,” ended in tear gas and blood on a bridge across the Alabama River. The second ended with a minister from Boston beaten to death. The third set out 8,000 strong on March 21 and came around a corner of six-lane Dexter Avenue in Montgomery four days later with 25,000 souls. That was the day King gave the speech now known as “How Long, Not Long”—

I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, however frustrating the hour, it will not be long.

But before the speeches, songs. Belafonte at a podium on a flatbed truck parked crosswise in front of the capitol, towering and broad in a dark zip-neck sweater, his arm around a blacklisted folk singer named Leon Bibb, who’s waving a little American flag with a sly smile, and Mary Travers of Peter, Paul and Mary, who’s twitching her perfect platinum bangs, wearing a tight white sleeveless shirt and tighter black-and-white check pants, swinging her hips in front of a seated MLK, who’s trying to peer around her. If you grew up on “Puff the Magic Dragon” you probably don’t know how absurdly sexy Mary once was. They all were, all three of them on that flatbed truck, desire and redemption and, in the middle, Mr. B, so beautiful he could be the solution to an equation. Solve for X, if X equals physical perfection. Behind them, hunkered in the capitol, the tragic little troll-man of segregation, George Wallace. Wallace said he did not care about the 25,000 people on his doorstep or the television cameras from all over the world. But Wallace didn’t matter. They’d already won, and they’d sing their song wherever and whenever they wanted. And they did, and they sang it terribly—maybe the worst rendition of “Michael, Row Your Boat Ashore” you’ve ever heard, their voices ragged and breaking into laughter and bumping into one another, Joan Baez off on the side soaring way too high above them. That didn’t matter, either, they were so tired and so glad, Leon, Harry, and dazzling Mary.

How long? Not long.

I ask Belafonte about that moment one day at a diner near his apartment. We’ve been talking about the decades since those years with King, since the April 9, 1968, march in Memphis Belafonte led in King’s place, holding the hands of King’s little children, after the bullet of April 4.

In Belafonte’s speech that day, recorded by network news, you can hear him fighting to hold on to some kind of calm, to some kind of future. “In the hope,” he says, “that the white world, in its bestiality and its decay, in its inability to understand the meaning of the black movement, in its inability to understand the compassion that black people are bringing to them, that the white man will be able to come to his senses. Because we find it increasingly hard to deal with his intellect, to deal with him in the sociological sense, but perhaps, after this, we might be able to appeal to his soul. Because that’s all that’s left.”

And then he walked away.

“Did you ever struggle with it?” I ask. Nonviolence, I mean.

“What do you mean, ‘did I ever?’ That’s all I struggle with, as a matter of fact.” He keeps all of King’s speeches on his computer. “I get in a real tough moment, I go into my computer, sometimes I don’t even know which one it is. I just need to hear his voice. It’s not self-asphyxiation. I’m not praising a deity. I’m living with a man that I remember.” He turns his head, smiles then frowns. “Now that you’ve elected not to be around here.” He’s addressing Martin. “Which was a very selfish thing to do.”

How long? Not long. But it’s been more than four decades now.

In early 1968, NBC asked Belafonte to take over The Tonight Show for a week. He agreed, so long as he had the freedom to choose his guests. Odetta, Aretha, Lena, RFK. Of course, King. “We came out. I said, ‘Martin, I was waiting for the tic.’ ” A tic King developed on the eve of the Birmingham campaign. Belafonte twitches in imitation. “What happened to it?”

“Well,” says Martin, “it’s gone.”

“When did it leave?”

“When I made my peace with death.”

Belafonte slumps in the booth. “I don’t know if I’ve made my peace,” he says. Sometimes he feels the loss of King as if it’s fresh. Not like you might have felt it if you were alive then, or, if you weren’t, like when you were a child in school and you first learned of the story and followed its terrible arc from Selma to Montgomery to Birmingham and finally to that balcony in Memphis. Not like that but like one of those frozen moments in history, a gunshot cracking through your imagination. As if imagination existed not for the sake of wonder but as a kind of clay with which to take impressions of the increments by which the world is always, slowly, drawing a razor across its own neck. It’s not the grief that’s fresh for Belafonte, it’s the gap: the awful absence of the other imagination, the what-might-have-been-but-is-not. What is left, in the place of that other imagination, is this still-beautiful, still-raging old man sitting across from you in a diner on the Upper West Side, turning his ravaged but still-seductive voice away from you to address the absence: “Now that you’ve elected to be gone.” Speaking to King as if he were here, sharing a lunch of clam chowder and raspberry soda.

Belafonte wants to tell me about a movie he never made, probably never could have made.

Amos ’n Andy. Not like Bamboozled, Spike Lee’s postmodern riff on blackface, but Amos ’n Andy as a history of minstrelsy going back to the beginning. It was the director Robert Altman’s idea. A movie of a minstrel show. White men in blackface who mimicked every brilliant song, every joke, every true story ever told by a black woman or man: stole it all and played it again, as both tragedy and farce, tragedy because it was farce.

“It’s about the mask,” Belafonte says, speaking in the present tense like he’s talking strategy and tactics, sipping Harvey’s Bristol Cream. “It’s about how much time people spend being false, how often we façade our behavior. Nobody’s better at that than the minstrels. And in them I see all of us. Everybody’s in the minstrel show. Behind the mask, you can say and do anything. The Greeks did it. Shakespeare used it when he wrote the jester. Those he could not give the speech to, he created the jester to say it. All of America’s problems are rooted in the fact that we’re all jesters. Not one of us truth tellers. So how do you get to the truth? Well, how do Amos ’n Andy do it? What’s behind the mask?”

This: In the mimicry and the falsehood, you can still find the roots of the song. “The art for me is how do you bend it your way?”

This: In the mimicry and the falsehood, you can still find the roots of the song. “The art for me is how do you bend it your way?”

Maybe it couldn’t be done. He told Altman, “You’re going to get us both fucking killed. Black people gonna be completely outraged. Don’t go to black people with blackface. And white people know it’s politically incorrect. There’s no audience.”

Altman said, “Except everybody.”

Belafonte’s quiet. Then: “But Altman left me here all alone.” Altman died in 2006. His last movie was A Prairie Home Companion. Belafonte shakes his head, talking to no one now. “Everybody’s in the minstrel show. Everybody’s a minstrel act.”

“The question you asked,” I say, “was how do you be a truth teller?”

Belafonte deadpans: “Find out what the reward is for truth telling.” He means, Martin found out. You get killed.

I say, “Maybe you get to stand on a stage in Montgomery at the end of a long march and sing a couple of songs.”

“That’s the best stage there is. Because in all these things there was death right afterward. Very successful march, boom, Medgar Evers murdered. March on Washington, then four little girls.” The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham. “Every time,” he says.

After that day in Montgomery, Klansmen murdered a mother of five who was driving marchers back to Selma. “After every great victory, a great murder.”

Then it clicks. The code. The murder is the blackface. It’s the cork. It’s the minstrel show, the act replayed, second time nasty.

“They’re gonna let you know you didn’t win,” Belafonte says. That’s why he’s been so angry, so long. It’s what keeps him alive. “Where your anger comes from,” he says, “is less important than what you do with it.”

What do you do with it? What he’s always done. You take it from the top. You sing your song again, until they hear it like it’s the first time. You make it your own, and then you give it away.

1 Comments

The first time I saw HB was at a Detroit, Michigan concert, circa 1957; my wife and I then decided he was the most beautiful man we had ever seen. The second -- and last time? -- was at Montgomery, Alabama, our having earlier joined the march from Selma. He was still the most beautiful man my wife and I had ever seen. He probably still is.

"How long?" All I know is that we've lived to see a black man in the White House. "Not long."