Doc Aberdeen looks more like a bricklayer than a doctor. In the front hall he hangs his hat on a spoke. His hair is center-parted so exactly that his white scalp shows through. I try not to look. Instead I fix my eyes on his leather kit of torture instruments, the black-brown handle worn pale from his grip. Once when he was in the john I opened it and saw its innards: hooks, scrapers, syringes, gauze. I guess I like him okay.

He hangs his jacket over his hat. There’re big half-moons of sweat under his arms. I can see his pink skin clear through the fabric. My eyes are on his monstrous shoes; two of mine could fit inside one of his, easy. He dries his face with a handkerchief (baby blue) and takes his time folding it and slipping it into his back pocket.

He turns to me with that unsmiling smile of his. “How about this heat, then, Sam? Staying cool?”

“No,” I say.

He laughs through his nose, and what a nose it is. Nostrils the size of half-dollars.

“You know it’s a hundred percent humidity today? At least that’s what the radio said on the way over. I’ve lived in St. Louis my whole life and I’ve never understood that. They say the Mississippi’s got a hundred percent humidity, so how could the air have a hundred percent humidity, too? Answer me that.”

It’s just adults asking you questions. They don’t want an answer.

I’ve got my thumbnail between my teeth and I’m looking at the rug like it’s got lips. I should offer him a glass of lemonade. Before he got sick, Houghton loved a glass of lemonade on a hot day. He’d pulp twenty lemons himself and drink it in a swallow. Things are different now.

I ask Doc Aberdeen if he wants to see him.

“I’d like a glass of water first, if you don’t mind. I’m parched.”

In the kitchen he sets the leather kit by the sink. I lean against the door frame. He fills the glass, drinks, and fills it again. The glass is tiny in his big hand.

“How was Grandpa this morning?” he asks.

He’s always called him my grandpa; I’ve never said he wasn’t. I shrug.

“The same? Worse?”

“Same.”

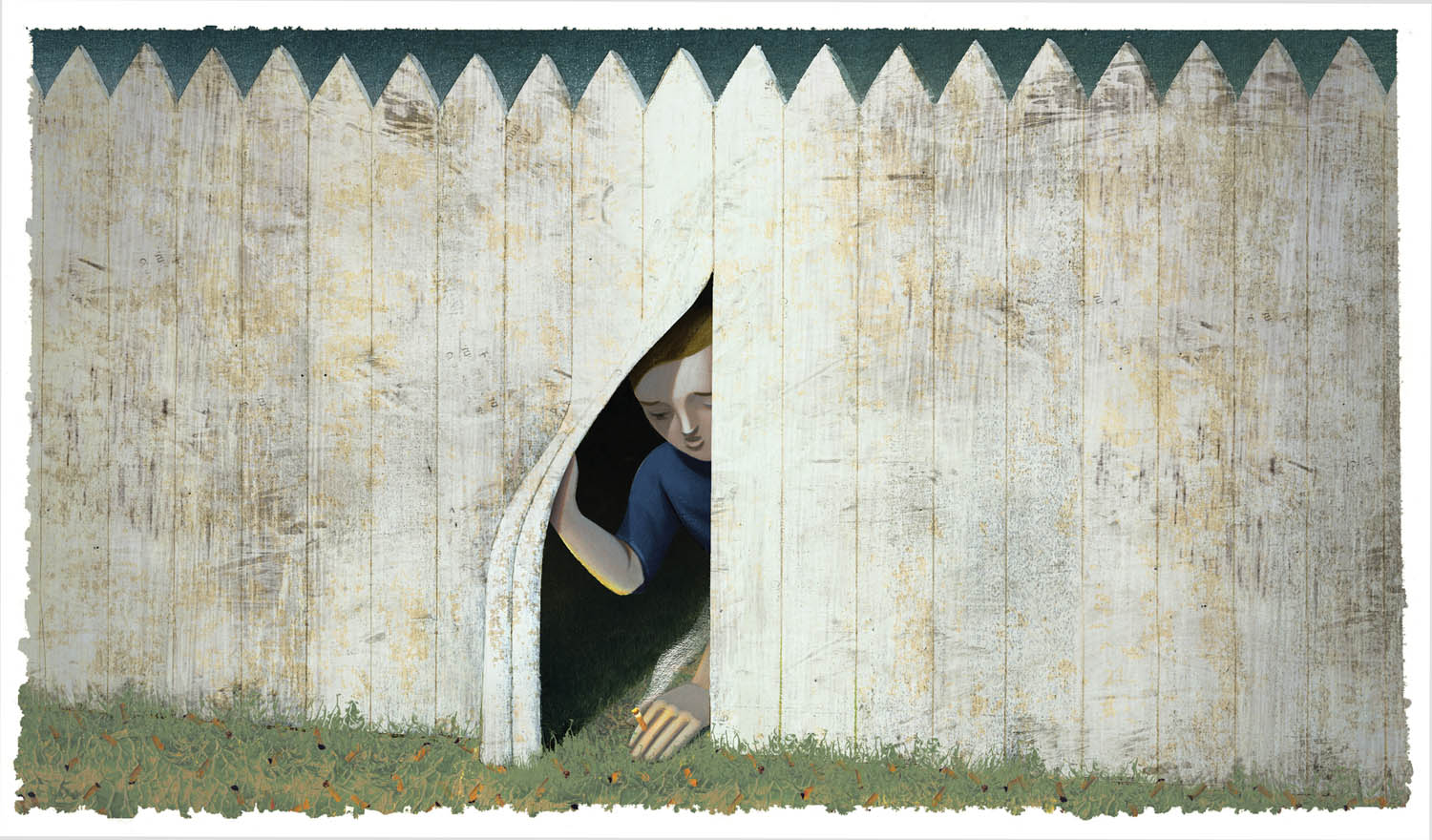

My eyes drift around the room trying to catch on something. Finally they land on the alley between our fence boards and the neighbors’. This is where the neighbor girl Ruthie meets me after supper, where we kiss until our lips go numb. Last night her mouth tasted like grape soda.

I’m asleep in my head, then I wake up. It’s one o’clock, but the light looks like 5 p.m.—you know, that sad, burnt yellow. Doc Aberdeen is watching me like he knows I was someplace else.

Early this morning Houghton woke me coughing. When I went in with a glass of water he was turned to the wall. The room was dark but I could see his stringy white hair spread out over the pillow.

“Have some water,” I said.

He hadn’t talked in days. I stood there with a jagged chunk of stone in my chest. The room looked like a tornado’d blown through it: clothes everywhere, towels, blankets. A tang of mold and urine. By my foot was a plate with a blond crust of something like apricot jam. He doesn’t like when I pick up after him.

He’d kicked the sheets away so I could see his whole shrunk-down body, his curtain-rod thighbones and his shoulder blades like some kind of bird’s wings. The way his ribs stood out made me think of an elder Christ, a Christ who’d lived.

I came around the bed and put my hand on his forehead. He stiffened but didn’t say a word. He was burning up and his eyes were shut hard.

“Have a sip of water,” I said. “It’ll make you feel good.” I put the glass to his lips and tilted it just so.

He managed to take some but went off coughing again like I’d forced gin down his throat.

“I’m just gonna sit here with you,” I said. “That okay?”

I think he nodded. My weight made his body slump into me. Neither of us moved. I hummed a tune for the noise. He was shaking pretty bad.

“The doctor’s coming today,” I said. “Remember?”

Houghton coughed once, hard, and swallowed the ones that wanted to follow. His eyes were open now but he wouldn’t look at me. They were black with anger and something else—fear, I think. How tight his skin was on his bones. Oh, he’d never looked so old.

I wanted to keep talking, but I couldn’t think of anything to say. I left the glass of water at his bedside.

At Houghton’s door with Doc Aberdeen behind me I knock once and wait for a response that doesn’t come.

“Doctor’s here,” I tell him.

Nothing. I open her up anyway.

Doc Aberdeen goes in and for some reason, I don’t know, I follow. Houghton’s lying motionless in bed, asleep or pretending to be. He’s underneath the blankets now and the glass I left him this morning is still half-empty. The room’s hotter than it was. The smell’s worse, too. Houghton can’t know how bad it is. A person gets used to any smell if they’re living in it.

While Doc Aberdeen’s going around the bed I draw back the shade. Light floods in. Outside, the maple tree’s in full bloom, leaves so green they look plastic. I slide the window open. There’s no wind to speak of.

Houghton starts coughing, real throat rippers.

Doc Aberdeen lowers his voice to Houghton like he’s a hurt dog. The torture kit unclasps and there are all the sounds a body makes squirming about in bed, but I don’t turn around. Doc Aberdeen says, “Sam? Come here a second, would you?”

In the sunlight Houghton’s skin is the color of cold chicken fat. Doc Aberdeen’s sitting in the exact place I was this morning, a stethoscope linked up between his ears and Houghton’s caved-in chest. Next to Houghton he looks bigger than ever. The old man’s eyes follow me as I make my way across the room, goose-stepping over debris. The hollow at the base of his neck is crosshatched with fine wrinkles. Doc Aberdeen takes the metal bits out of his ears and fits them into mine.

“Listen,” he says.

My first thought is of water, violent water that can suck a grown man under and keep him there till he’s drowned, water you can’t reason with. It doesn’t make sense to me, that this sound’s coming out of that body. From the look of it there’s hardly any life in him at all, just vapors.

I take the metal bits out of my ears.

“Know what that is?” Doc Aberdeen asks.

I shake my head. Houghton’s lips are turned down, sucking in a cough. His wild eyes. His sharp-boned shoulders.

“That’s the sound of a healthy heart.”

Houghton looks from the doc to me, that dark look in his eyes again.

“You’ve got the heart of an ox,” Doc Aberdeen says. “Listen yourself if you don’t believe me.”

“Your heart sounded good,” I say. Houghton stares at me so hard I have to look away.

Doc Aberdeen squeezes my arm. “You can wait for me downstairs, Sam. I’d like to talk.”

Around here’s old money, but the houses aren’t much to look at. Red brick, two stories, a little yard. Big garages that were built for horse and carriage now house the family car. These houses are as old as the city itself. Bankers, lawyers, judges, surgeons, doctors. The last mayor lives at the end of my street, but no one looks at me like I’m anything more than a shoeshine boy. They know I’m different—they know I come from Chicago, and who my pop was, and what it is he did for a living.

I knew who Ruthie was before we met. I know who all the neighborhood kids are and what their fathers do. But I took an interest in Ruthie. I like to think that’s not just because she took an interest in me.

She’s one of those people who is their name. She’s small for fourteen and she looks even smaller because she keeps her shoulders shrugged up like the world’s gone cold. Her hair isn’t red or brown but the exact color of a penny—and soft. Hers is the first woman’s hair I’ve ever touched on purpose.

Twenty-three days ago I was out in that alley behind the fence boards smoking a Lucky Strike after dinner. The moon had come out, but the sky wasn’t dark yet. The blue was starting to get deep, though, and the few clouds there were looked heavy and bruised like in old paintings. Mosquitoes were sampling my ankle. When I looked down, little Ruthie was standing right in front of me like she’d grown out of the dirt.

“I can see your smoke from my bedroom window,” she said.

Downstairs I sit on the bottom step, arms on my knees. The house is so quiet it may as well be empty. Doc Aberdeen’s jacket is right there beside the door. I decide to go through the pockets. Nothing against him, it’s just a dare with myself, the devil in my head guiding my hand.

The only thing I find is a grocery list, the writing cramped: bread, tomatoes, milk, hamburger, onion, chocolate. I tuck it in my pocket. I’m still standing there when an upstairs floorboard cries out. Next second I’m back on the step with my temple against the banister. I move aside so the doc can get past.

He sets his kit down and wipes his face with his blue handkerchief. “He’s a tough old crow, your grandpa.”

“His heart sounded pretty good.”

“I did say that.” He puts on his hat and drapes his jacket over his arm. “I don’t know if he heard me. I wish I had some good news for you.”

“Is it his lungs again?”

He picks up the kit. “I would say he should come back to the hospital for more tests, but that might upset him. And to be honest, I don’t know what good it’d do. You should change his sheets. I could tell they haven’t been changed in a while.”

“He doesn’t like me touching anything.”

He looks me up and down. “Isn’t there someone who can be here with you? A relative? A family friend?”

I shake my head.

“Everything will be okay. He’s a tough old crow.” He smiles with one side of his mouth.

Ruthie’s home from school at three. At half past, I head over. I lift up the loose fence boards and duck into the alley. The grass is patchy and yellow as straw, littered with cigarette butts. Her house is right behind mine. I told her how if you take the right nails out of the fence you can sneak underneath, so I crouch down and skulk down the row, pushing on her fence boards until I find the loose ones.

In the center of her yard is a stone birdbath. There’s a blue jay on the rim, not drinking.

Ruthie’s bedroom is the upper-right window. I take up a handful of acorns from the grass and toss one up. I’m about to toss another when her face appears behind the glass. She opens the window and leans out smiling.

“You.”

“Come down.”

“My dad’s asleep.”

“So come down.”

She looks behind her, then disappears. I drop the rest of the acorns in the grass and walk over to the birdbath. The blue jay is gone. With the sun behind me my reflection in the water is too dark to make out. I splash my hands and smooth my hair flat.

Ruthie comes around the side of the house still wearing her school uniform: a white dress shirt underneath a dark-blue sweater. She hugs me hard enough to crack two ribs.

“Aren’t you hot?” I ask.

“Oh, you get used to it. At school I have to wear gloves.” She grabs my hand and pulls me toward the fence. “Now, I should be studying for geometry. If my dad wakes up and looks out the window I’m dead meat.”

As soon as we get into the alley we start kissing. I keep my eyes open; hers stay closed. She looks so peaceful she could be asleep, but her tongue is going wild against mine.

After a while, I don’t know how long, we break apart. I reach for my pack of cigs.

“Don’t. My dad’ll smell it on me.”

Her old man was a pitcher for the Browns before he retired at forty-four. Now he sits around the house in his bathrobe all day, drinking highballs and smoking cigars.

“He’s mean when he’s got a night hangover,” she says. There’s a strand of hair glued to her forehead. I remove it and tuck it behind her ear.

“How was school?”

“Rotten. I wish Mary Institute would burn to the ground. Every girl there is a GD phony. I found out Anne Louise is having a party at her lake house this weekend and I wasn’t invited. I asked her about it and she said my invitation must’ve gotten lost in the mail—not that I could go, just that the invitation must’ve gotten lost. She wants me to ask if I can go. Well, she can forget it. She makes me want to puke.”

“I wish I had a car,” I say. “I could drive away from here.”

“And leave me stranded?”

“You’d be my copilot.”

She smiles. There’s the slightest gap between her front teeth. The pink of her tongue shows through. “Where would we go?”

“South America, maybe?”

“We can’t,” she says. “The Panama Canal, remember?”

“I’d drive to the canal, then. We could swim across.”

She pulls me into her by the back of my neck. This time I shut my eyes, but I can’t help thinking of Houghton lying awake all alone in that hellhole. I imagine him calling out for a glass of water, a bowl of beef broth.

“Look,” I say. “Can we get out of here?”

She laughs. “We can’t go to South America.”

“I don’t mean that. I mean out of this alley. Downtown or something.”

“My dad might wake up.”

“You said he’s passed out.”

I can see her thinking on it. “Just an hour, okay?”

“An hour,” I say.

The alley spits us out on the street. The blacktop is soft under our shoes. We pass through a pool of shadow, then the glint of a fender blinds us. The air smells of freshly mowed grass. She doesn’t hold my hand or link her arms with me and I can’t blame her. She’s her and I’m me.

We come to the end of the block and turn right, down Olive Street. Parked cars up and down the block—Chevy Coupes, Fords. I watch us float past the windows of the supermarket, the five-and-dime, the bakery. Ruthie’s a head shorter than me. In the light her hair is flaming red.

She takes off her sweater and ties the arms around her neck. I grab the back of my shirt and shake it for a breeze.

Out of the blue she asks, “How’s your grandpa?”

“Fine,” I say.

“I thought you said he was sick.”

“Not anymore. The doctor said he’s got the heart of an ox.”

By the time we reach Sixth Street a long time’s gone by, at least a half hour. Still, we don’t rush. It’s like a dream, Ruthie and me walking so slowly through the shadows of the city’s hotels. The streets are deserted. The trolleys are empty. We sit on a bench in front of the courthouse green. The wooden slats are hot through our clothes. Ruthie looks around, then rests her head on my shoulder.

“Where do you want to go?” she asks.

“I don’t care.”

“I’m hot.”

“It’s a hundred percent humidity today.”

“You know Anne Louise’s family has an air conditioner in their house? She’s so spoiled. And for lunch, guess what? She never drinks milk, only Coca-Cola.” She fans herself. “I want to go somewhere cool and dark and have a Coke.”

“There’s a billiard hall down on Market. We could have a Coke at the bar.”

“Don’t be dumb. They won’t let us in.”

“Why not?”

“Aw, stop fooling. We’re kids.”

“They’re old friends of my grandpa’s,” I say. “They’ll let us in.”

The only reason I know about Floyd’s is because Houghton took me there when we first came to St. Louis. He showed me off like I really was his grandson, sat me on a barstool and spun me around. Everybody knew who I was, who my pop was, and what’d happened to him. Men with red faces pinched my cheeks, tousled my hair. That was the winter of 1932. I was eight years old.

Ruthie follows me down a set of three stairs. Glass shards crunch under our shoes. At the door, I slam the heavy brass knocker against the wood, but no one answers. When I try the knob the door swings open.

The place is completely gutted. Smashed furniture, rubble, wallpaper hanging in scrolls. In places I can still make out the black-and-white tile floor. Ruthie stands in the doorway as I make my way forward. I run a finger along the bar, collecting dust.

“The pool tables were in back. And the card games.”

“Your grandpa brought you here?”

“Sometimes,” I say. “If he felt like it.”

She comes up behind me and wraps her arms around my chest. “My boyfriend is dangerous. He’s a hoodlum.”

“Quit it,” I say.

I keep going. The door that led to the back room is gone, not hanging from a hinge or lean-to’d against the wall—I mean gone, disappeared. It’s too dark to see inside, but I remember the room was long and low-ceilinged and the walls were yellow from cigar smoke. In this room I once shared a chair with Houghton while he played blackjack.

“Hit me,” I told him. “Stay. Stay. Hit.”

He ordered me sparkling apple juice in a champagne flute. Now it’s like being in a cave.

Instead of going back we head toward the river. We don’t talk about it; our footsteps just lead us that way. The light’s really starting to thicken up. Shadows stretch out from under cars. Ruthie buys a bag of roasted peanuts from a street vendor and shakes some into her palm. She’s looking at me, chewing.

“How’d you say your grandpa made his money?”

“I told you. Oil.”

We wend past men in gray suits, black suits, blue suits. For a long time we’re stuck behind an old Negro lady pushing an old white lady in a wheelchair. The skin of their elbows is all puckered and gray.

I smell the river before I see it—dank like sulphur. I walk faster, to put bodies between Ruthie and me. Between two brick warehouses, the river comes into view. All that brown water. Only then do I slow down.

“What bit your behind?” Ruthie asks me.

“Nothing,” I say. “Come on.”

The grass between the warehouses comes up past our knees. Our footsteps squelch in the mud, sucking at our shoes, not wanting to let go. A hundred yards downstream the Eads Bridge stretches across the water into Illinois. The current washes white around its black iron legs.

At the riverbank Ruthie raises up on her tiptoes and kisses me. I keep my hands at my sides and breathe in the smell of her shampoo. Then she breaks away. She slips off her shoes, clutches the hem of her skirt, and steps in. I kick off my shoes, peel my socks away. I don’t bother cuffing up my trousers. The water feels like a hot bath. The current pulls gently at my calves.

“My dad might kill me,” she says. “But this is worth it.”

She drops her paper bag of peanuts. We watch the current carry it away.

“You think anyone’s ever swum it?” I ask.

“The Mississippi?” She laughs. “It’s like a quarter of a mile.”

“It’s not that far.”

“The current’s too strong.”

“How about to the bridge, then? Do you think I could do it?”

She looks up at me. “Don’t be dumb.”

“It’s not that far,” I say.

“What the heck would you do that for?”

“Do you think I could do it or don’t you?”

I’m already unbuttoning my shirt. I ball it up and fling it into the grass, unlatch my belt buckle, and strip to my undershorts. Ruthie puts a hand on my shoulder, but I shrug it off and dive in. I start swimming as hard as I can.

I’m thinking of our first Christmas in St. Louis, mine and Houghton’s, when the old man gave me a pair of ice skates. He bought a pair for himself, too. That afternoon he drove us to the river in his Ford. It was an arctic winter. We’d already gotten a lot of snow and the river’d frozen over; usually that didn’t happen till February if it happened at all. There were skaters on the ice when we got there. Clusters of families, people skating alone and in pairs. Houghton and I hobbled out on the ice. We stayed together at first, kicking out, drifting, kicking out again when we slowed down. My face burned with cold. I tucked my chin into my scarf. The next time I looked up Houghton was way ahead of me, apart from everyone, almost at the opposite bank. He cut a long, slow turn in the ice, saw me, and raised a hand as he got closer. Even from so far away I could see he was smiling.

The river isn’t as strong as I expected, but it does have muscle. I swim the length of the first bridge leg then let the current take my body. Twigs, leaves, and scum float along with me. I get swept against the steel and grapple up onto the crossbeams until I’m completely out of the water. The beams are slimy and green with algae, the spaces between them filled with intricate spiderwebs and insects cocooned in silk. I climb three rungs higher, to where the metal’s flaking off. For a while I just hang on, catching my breath. When I turn around, I can see Ruthie picking her way through the reeds along the shore. She’s got my clothes bundled in her arms and she’s calling out to me. Her voice sounds like a gull. I climb down slowly and let my feet hang just above the surface of the river, in that place where water touches air.

On the walk home my wet shoes rub my heels raw. Ruthie carries hers in her hands and talks the whole way back about what a fool I am. She says the river’s got sharks in it, didn’t you know? Freshwater bull sharks that could swallow you whole.

I keep half a step ahead and make sure she doesn’t step on broken glass. The shadows are longer on the lawns, deeper. The air’s cooler, too, but maybe that’s just the water drying on my skin. We say so long at the end of her street without a kiss goodbye.

Soon as I come into the front hall I slip off my shoes. The sores are inside out and ringed with mud. In the kitchen I soap up a rag and work my heels over as gently as I can, but the sting brings tears to my eyes. The smell of the river rises off me as heavy as gasoline.

I follow myself upstairs, floating along the ceiling. I can’t feel the pain in my heels or the rugs under my feet or the fabric of my clothes against my skin, not until I come to the top of the stairs. That’s when I drop back into myself. My heart’s going like a sparrow trapped in a man’s hands. When I come to Houghton’s door, I stop. Inside, everything looks like it did hours ago: the sheets kicked away from his ruined body, the debris of bedding and clothes, the water glass untouched at his bedside. I shift my weight. A floorboard creaks, but Houghton doesn’t stir. Outside, birds call to each other in the branches of the maple tree, unseen. I like the doorway because it isn’t this room, but it isn’t that one either.