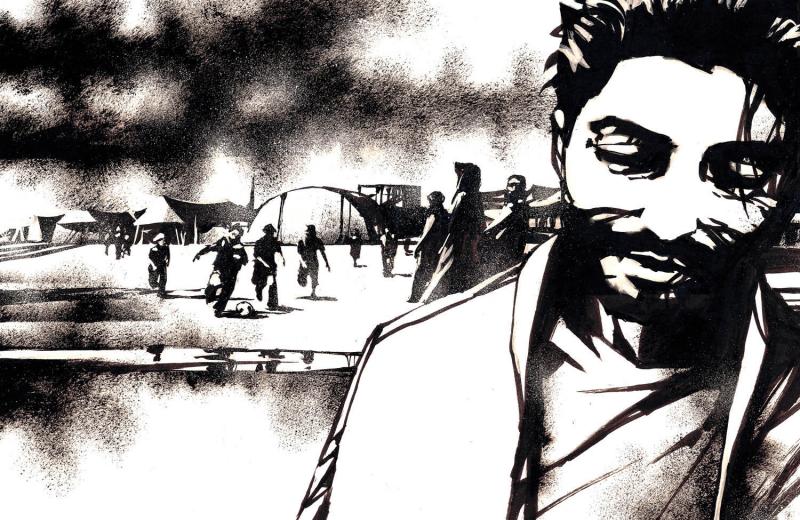

Yakzan Shishakly had been working as the unofficial manager of a Syrian refugee camp for about a year when he was kidnapped by the people he was trying to help. It was summer 2013 and Shishakly, an affable and earnest thirty-six-year-old Syrian-American, was there for one of his regular visits. The camp, known as Atmeh after the Syrian town closest to it, is situated on a gently sloping field of packed dirt and low-lying brush, along a featureless stretch of the border near the Turkish town of Reyhanli. When Shishakly first laid eyes on the camp, the summer before, only a handful of families were there, taking refuge in the shade of an olive grove. By winter their numbers had risen into the thousands. With fuel growing scarce, and with no expectations of being there the next summer, refugees cut down most of the olive trees for firewood.

Because Atmeh is in a rebel-held part of Syria, where a brutal and destabilizing conflict has been underway since 2011, it inhabits a space that often seems to fall between spheres of responsibility. The Syrian government has no meaningful presence in the northern borderlands, other than to periodically send warplanes to drop bombs. The Syrian opposition, meanwhile, remains fractured and resourceless, providing little more than infrequent expressions of outrage and pleading press releases on the camp’s behalf. The Turks, who have built state-of-the-art facilities for refugees within their borders, monitor the camp from afar, but mainly to contain rather than intervene. And the United Nations, in a perverse twist, can do little but watch: Barred from operating in a sovereign nation without that government’s permission or a Security Council resolution, its officials have been largely unable to set foot inside northern Syria, let alone turn Atmeh into a proper refugee camp like those in Jordan or Turkey. The line separating Turkey from Atmeh, demarcated by as little as a waist-high stretch of barbed wire, might as well be a towering fortification.

In this sorrowful morass, Shishakly thought he glimpsed an opportunity. He had come to Turkey from his home near Houston, Texas, soon after the start of the Syrian uprising, determined to contribute in some way to the opposition. Shishakly’s grandfather, Adib Shishakly, had been one of Syria’s last presidents before the country fell into the hands of the Ba’ath Party and the family of Syria’s current president, Bashar Assad; the elder Shishakly had provided postcolonial Syria’s first sustained period of political and economic stability. It only seemed logical to Yakzan that a democratic revolution against Assad would include a role for him and his venerable family name.

After Yakzan arrived in Reyhanli, where many Syrian-run humanitarian organizations are based, he began to venture into northern Syria, eventually finding his way to Atmeh in the summer of 2012. By then, the build-up of people at the border had spiked, after the Turkish government stopped letting Syrians flow freely into their country. As the fighting and bombardment of Hama and Idlib provinces raged, the displaced kept arriving in droves. In Houston, Shishakly had run a small heating-and-cooling company in the suburbs, and what the Atmeh encampment seemed to need most was someone with business acumen and a touch of entrepreneurial spirit. He created a foundation, which he called Maram, and set about securing contributions from Western nations and private donors while orchestrating the distribution of aid within the camp.

It was exhausting work, but also deeply rewarding. Within a few months, resources were flowing steadily into the settlement. Private aid groups had begun to deliver food and tents, and to construct bakeries and schools. Life for the refugees was improving. Residents started getting used to seeing Shishakly every day, and they took to calling him mukhtar, or mayor.

But there were also signs of discord. Religious extremism was on the rise. The food and water that made its way to Atmeh was never enough, and tensions between factions of the displaced, many of them heavily armed, flared repeatedly. More than once, Shishakly had to slip away from a heated argument between beneficiaries, lying low in Turkey while things cooled off.

On the day of his kidnapping, he wouldn’t get away so easily. As he pulled into the camp, he saw a group of men, some affiliated with brigades of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), facing one another down amid a cluster of tents. Guns were being fired into the air, and more armed men were arriving by car from the town of Atmeh. Shishakly stood to the side and watched, hoping not to be dragged into the melee. Then a man with a Kalashnikov drove up beside him and said, politely but firmly, “Get into the car.”

The ordeal lasted only a few hours. Shishakly describes it as more unsettling than frightening. “I never felt scared,” he told me. “They just wanted to send me a message that I didn’t have any real power.” Like so much of the Syrian uprising, the atmosphere of Atmeh had been changing: Once the site of dedicated volunteers seeking to ameliorate misery, it had devolved into an arena for warlords and racketeers, each grappling for power and profit. Shishakly had clearly angered the wrong person—although he wasn’t sure exactly whom. He was released unharmed, but when it was over he knew his work at Atmeh had taken an unexpected turn.

Several months later, in early February, Shishakly was cruising down a two-lane highway toward Reyhanli in a white Hyundai Accent, on his way to visit Maram’s local office and to check on an orphanage for Syrian refugee children he was helping to build. He was dressed in blue jeans and dark sneakers, wearing a hooded sweatshirt against the morning chill. Shishakly is a tall and hulking man. His hair, once shaggy and untamed like a surfer’s, had grown out into dark, rigid streaks, although wisps of his bangs still sometimes fell across his face, obscuring his eyes.

After the kidnapping, Shishakly had moved away from Reyhanli, taking an apartment in Gaziantep, a mid-sized Turkish city a hundred miles to the northeast, where much of the international humanitarian apparatus is based. He hadn’t returned to Atmeh since the summer, and his outlook on the experience had darkened considerably. “I was getting so depressed,” he said of the days after he quit Atmeh. “I never thought we would see Syria get so bad.”

Despite his recent disappointments, the wizened, wearier Shishakly still seemed to possess many of the qualities his friends use to describe him: a relentless sense of purpose, tireless drive, a touch of absent-mindedness. (He had forgotten his cell phone back in Gaziantep, and throughout the day, whenever he needed to make a call or send a text, he kept having to borrow one from a colleague.) When Shishakly was young, growing up in the Syrian province of Hama, he was renowned among his siblings for being almost reflexively generous. His older brother, Adib, says that Yakzan often gave away his lunch money to other kids, sharing snacks and sodas with anyone around, sometimes going hungry. Later on, when Yakzan traveled to the US to study and pursue a career in business, he frequently seemed indifferent to basic matters of finance or any of the mundane details of life in the States. After he moved to Turkey in 2011, his savings quickly dwindled. His air-conditioning business languished and eventually went under. “To be honest, Yakzan was never very interested in making money or being in the US,” Adib said. “He went there, stayed for a while. But his heart and soul was always in Syria.”

As we made our way down the Reyhanli highway, the late-morning sun began to warm the air, and Shishakly rolled down the windows of his car. The farmland around us was wide and expansive, a broad field of vivid lettuce buds and stalks of corn atop the churned earth of tractor-plowed reddish soil. The air smelled like a backyard garden: the sweet, acrylic aroma of fertilizer and fresh vegetation. Off to the right, a jagged silhouette of low mountaintops marked the edge of Turkey and, just beyond that, Syria.

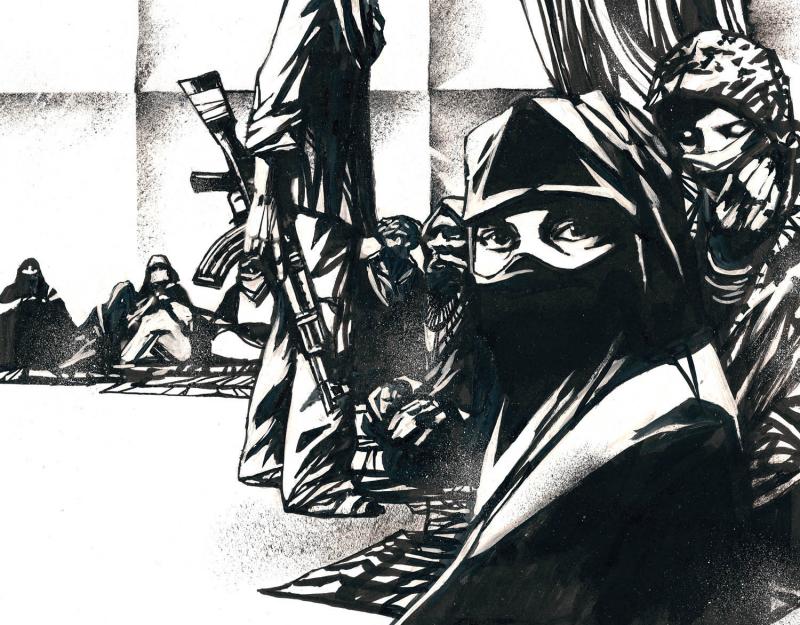

When Shishakly first came to this area, he’d crossed over those mountains and felt, for the first time in his life, “like I belonged to this land.” That morning in the car seemed an impossibly long time from those hopeful days. Over the previous months, the downward trajectory at Atmeh had been matched by a similar turn of events across northern Syria. As the rebel advance on the regime stalled, the besieged territory controlled by the opposition began to fester. Criminal gangs proliferated, and, worse, a series of radical Islamist groups began seizing territory from the Free Syrian Army—liberating land from its liberators, as secular opposition activists put it. The worst of the radicals, a group known as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), was turning swaths of the country into an impenetrable terrain, kidnapping journalists, assassinating foreign-aid workers, and driving out less devout Syrian activists—a harbinger of the malignant campaign of terror and conquest the group would soon mount next door in Iraq.

Activists and early supporters of the Syrian uprising were aghast at the turn of events, and infuriated by the tepid international response. It was difficult to understand how the West, and especially the United States, could apparently abandon a rebellion it had done so much to encourage. By not providing the Free Syrian Army with the sort of sophisticated weaponry that might have held off the Assad regime’s air force, activists and opposition leaders believed, the West had made it harder for moderate rebel brigades to prevent qualified fighters from defecting to the better equipped, more radical groups like ISIS.

Even more galling, many felt, was the failure to offer sufficient humanitarian relief to the people who arguably needed it most: the millions who were displaced within the country, in places like Atmeh or across the northern countryside. Fleeing bombardment and urban warfare, these people (estimates put their number at more than 6 million) had taken shelter wherever they could—abandoned homes, damp caves, olive groves—and were often forced to relocate as the war encroached on their places of refuge.

The United States, for its part, has sent more than $2 billion to the humanitarian campaign in and around Syria, but only a fraction of it has trickled down to people inside. Atmeh’s proximity to Turkey, where the government runs a facility for Syrians that the New York Times described as the “perfect refugee camp,” makes the disparity in conditions particularly tough to reconcile. “How in the world can you be six inches from the border and not be able to coordinate aid?” a Syrian-American relief coordinator in southern Turkey told me. “It just doesn’t make sense. It’s a place where things should have been fixed really easily, should have been addressed with care. The response to Atmeh is what I would call a categorical failure on the part of everyone involved.”

This past July, the UN voted for the first time to begin limited cross-border aid deliveries, over the objections of the Syrian government. The first shipments arrived later that month, more than three years after the start of the uprising.

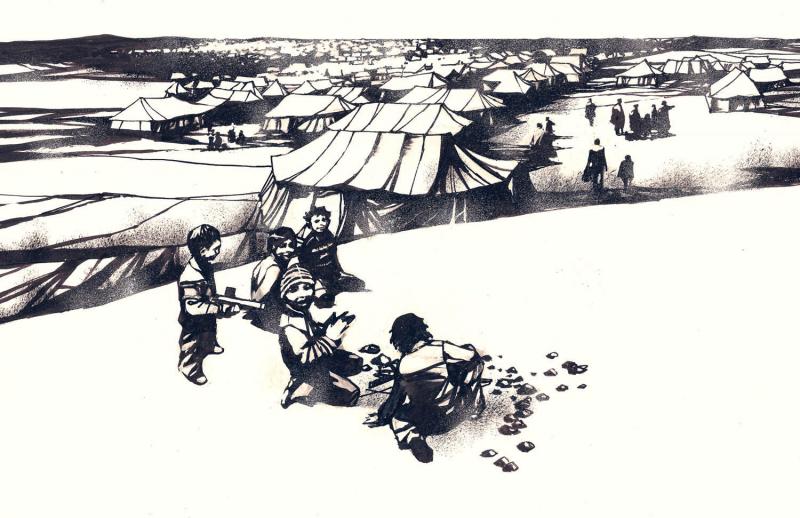

Refugees and the displaced never have it good, but by all accounts the conditions at Atmeh by late 2012, when its population was estimated at roughly 15,000 people, were especially wretched. (Atmeh’s population is now believed to be closer to 30,000). In March 2013, the UN conducted a satellite survey of the area and counted around 2,000 tents in a sprawling mass. Two months later, a second tally found more than 3,000 bunched together over two discrete areas—an increase of almost half.

The camp was slowly but undeniably becoming a slum—one that under any other circumstances would be considered uninhabitable. The refugees at Atmeh had just endured the second winter of the war, many of them suffering through it without heat, electricity, running water, or decent toilets, only to find their problems were getting worse. Desperate to keep warm, many took risks—with catastrophic effects. Over New Year’s, a tent fire caused by a family burning a kerosene lantern killed two children and left several others in critical condition. Lina Sergie Attar, a Syrian-American writer and humanitarian worker, happened to be in the camp shortly before the fire, and she met a twenty-year-old mother of two named Manar, who told of a similar experience. Manar had left her young children asleep in their tent while she ventured across the camp to a bathroom facility reserved for women. When she returned, she saw plumes of smoke coming from her corner of the camp, and realized the candles she had left burning for warmth must have caught fire to the tent’s fabric. Both of her children were killed. “I fled with them here from so far away to be safe,” the bereaved mother told Attar at the time. “They were my entire life. I don’t care about my life anymore. I lost my home, my children, my possessions, what’s left to lose? All I have is dirt.”

Donations arrived from outside the camp inconsistently, said Haitham Shaqfah, a pediatrician who ran a clinic there during the early part of 2013. “Sometimes we had all sorts of donations—food, tents, blankets—and the situation would become acceptable. But then there would come a month or two months with no donations, or very few. Everyone in the camp would find themselves in a very bad place.” Children developed scabies, lice, and measles, Shaqfah said, and the difficulty of acquiring inhalers meant that something as simple as a case of asthma—agitated by the foliage of the remaining olive trees—could prove deadly.

By then Atmeh was showing signs of permanence, something that made many people there anxious. When an aid organization began constructing a playground in the spring of 2013, the workers were met with scorn. “What’s the use of this?” one man told a Syrian journalist who had come with the group. “We don’t want to stay here. We want to return to our homes.”

For a time, forces affiliated with local units of the Free Syrian Army kept order and security at the camp, but they, too, were living with their families in the same squalor, compelled to compete with one another for basic necessities. (At times, they also attracted the unwanted attention of the Syrian military, which targeted areas near the camp with at least two airstrikes in 2012.) There were tensions with just about everyone and between everyone. The olive trees that the refugees had cut down that first winter belonged to neighboring farmers, who were furious but outnumbered. “Every farmer came when they saw their land without trees,” said Omar Bakkour, a Syrian who worked in the camp as a liaison for the aid group International Medical Corps, a large, US- and UK-based agency. “They came and they screamed at the refugees and then they left. What else could they do?” The town of Atmeh itself, just over the hill from the camp, was a smuggling hub and was filled, even before the uprising, with a startling array of reprobate characters. The roads between Atmeh and Reyhanli were slick with diesel from the night traders, and weapons dealers often used crossings close to the camp to move arms and foreign fighters into the country. Needless to say, many resented the increased spotlight brought on by the arrival of international organizations at the campsite. Others sought a cut of the spoils—one visiting journalist dubbed them the camp’s “king rats.” As 2013 wore on, the town also became a base of operations for a well-equipped Islamist brigade that seemed to be lying in wait for a chance to attack the moderate fighters. Syrians at the camp referred to them mockingly as “the spicy crew,” but they presaged the possibility of open conflict between anti-Assad groups in the region.

Attar visited the camp once in December 2012 and again in June 2013, and observed that its character—of a tolerable place of refuge—had changed markedly, with an especially troubling rise in criminality. “You could tell instantly that it was a different place than I’d been to before,” she said. “There were places you couldn’t go alone as a woman.”

Refugees at the camp who were frustrated by the shortage of resources often turned their discontent on the people who were in charge. An Egyptian activist who visited the camp found himself swept up in a wave of residents who were angrily protesting the aid groups that they believed were hoarding food and other resources. The crowd gathered outside a camp warehouse, demanding access to it. Finally one of the protesters broke down the door, and the crowd stormed in. “They were grabbing everything from the inside, anything they could,” the activist recalled. “But all they were grabbing were empty cups, plastic chairs. There was nothing in the storage. It was empty.”

Shishakly likes to say that he’s not sure if he chose to remain in Turkey after his first visit or if he “just got stuck here.” The conflict has drawn in many expatriates over the years. In places like Reyhanli, an influx of Syrian do-gooders has helped turn a sleepy border town into a major hub for relief operations. They all wanted to play a role in what they imagined, with almost utopian fervor, would be a new Syria. Some of these activists were better equipped to help than others, and the bar for creating a humanitarian NGO was low—it often required little more than a color printer and a wealthy contact in Qatar. “I call it the twenty-eighty rule,” the Syrian-American relief coordinator said. “Twenty percent of the organizations do eighty percent of the work.”

Shishakly’s organization was one of these start-ups, but he was determined to show that he belonged among the 20 percent. He hardly slept during his first months working for the camp. “At that time, we often didn’t even know what day of the week it was,” he said. “We just woke up in the morning, went into the camp, and worked.”

Using an office he and Adib had borrowed from another NGO, Shishakly created a coordination committee for various NGOs that operated at Atmeh. Adib had joined the political wing of the opposition back in 2011, and through his connections the brothers were able to make a deal with Turkish authorities to turn a small road leading to Atmeh into a permanent access point for humanitarian workers. On those preliminary forays into the camp, Shishakly learned of a desperate need for potable water, so he arranged with the Turkish Red Crescent to deliver water tanks from Reyhanli. Seeking additional funding, he also gave tours of the camp to representatives of Gulf oil barons and Western governments, hoping to persuade their bosses to contribute funds.

By the start of 2013, Shishakly became convinced that to really impact conditions at the camp, he would have to do more than assist it piecemeal. A few weeks earlier, his foundation had opened its first permanent project at Atmeh, a small kitchen that would go on to serve more than 15,000 people a day. But efforts like this still depended on outside agencies for supplies, including, Shishakly hoped, the United Nations. In January, he finally managed to arrange for a delivery of goods from the UN—a shipment of 1,000 tents. It was, at best, a dispiriting exercise. As part of the arrangement with Damascus, the tents had to be routed through government-controlled territory into the hands of the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, a government-approved organization that was often the only Syrian group serving opposition areas. The SARC team did little to distribute the tents, other than to dump them in an open area near the olive grove. Fights broke out as refugees scrambled to collect the goods. “They did the worst aid delivery of all time,” Shishakly told me. “It caused more problems than it was worth.”

As his organization expanded, opening a small school and a women’s center, Shishakly became a regular presence at the camp. When he walked among the tents, children would follow after him, begging for food or toys, and adults would hand him slips of paper with their requests written out. He sometimes fulfilled them, and sometimes didn’t. “I didn’t want them to think we always have everything available right away,” he said of the informal system he’d developed. “It’s like buying time, but also about avoiding a dependency. If they think I’m totally in charge and they think I can do anything, then they don’t think about other options.” He insisted that he never did this to a refugee who was in dire need, only those seeking something superfluous.

Shishakly had already learned that there were limits to what could be achieved through generosity alone. Atmeh was divided into sections, each with its own leader and community council, and Shishakly noticed that if he provided a certain benefit to the people in one section, he would quickly have to do so for others or face a barrage of accusations and complaints. “If I sat with one group of people for a whole day but didn’t pass by another group, the other group would get mad and create problems,” he said. “This happened all the time.” Lina Attar once walked through the camp with Shishakly and saw how he attempted to manage this dynamic. “There were kids all around asking him for soccer balls, but he only had ten of them,” she said. “He wanted to give them out, but he couldn’t—he knew if he did, they would fight over them. Later, when I went back to my hotel, I called Yakzan to see what he thought the camp needed, and he said, ‘Buy soccer balls.’ ‘How many?’ I asked him. He said, ‘Twelve hundred.’ ” He’d planned to give one to every tent that had a child.

There was only so much Shishakly could do to contain the expectations of everyone in the camp—or supervise everyday goings on. Even as he worked to create a systematic process for relief distribution, circumstances often undermined him. In some cases, it came from refugees who were simply doing what was necessary to survive—bartering excess supplies to stave off hunger, for instance. Others had darker motives. Some of the first to arrive in the olive grove had acquired extra tents and started to lease them to newcomers. Omar Bakkour told me that some refugees had even become de facto slumlords, claiming ownership of parcels of land and making new refugees pay for the space—but leaving them to find their own shelter and supplies.

Meanwhile, mixed in among the genuinely needy refugees were smugglers and profiteers who siphoned off donated goods and sold them to the residents under their control—including some of the section leaders. The problem was exacerbated when the international agencies began to arrive in force. Shishakly was frustrated by the outside groups’ practice of hiring refugees to work for them—he felt it undercut the atmosphere of community and collective self-sacrifice that had served the camp well in its early days. “For the first five months, everybody was a volunteer and nobody asked for any payment,” he said. “After the international organizations came, nobody volunteered anymore.”

Worse, the agencies often donated goods without regard for actual need. In the winter of 2013, this was particularly problematic with blankets, which are a popular item for outside relief organizations to donate because they are easy to send, photogenic, and simple to explain to their funders back home. But at a certain point, Atmeh had all the blankets it needed, and the extras were being diverted into the black market. Shishakly tried to impress upon donors that they should find other goods to contribute, but his warnings had little effect. “They really don’t need blankets anymore,” he told me at one point, “but donors like to give blankets, so they keep giving them.”

A veteran Syrian aid worker whom I’ll call Abu Gharbeh spent much of 2013 in Atmeh and observed a similar situation when a small aid group did an unplanned distribution of shoes. “They brought three or four thousand shoes, and they put them into the warehouses, and then just started passing them out through the windows,” he said. “It was total chaos, and it was not a dignified or intelligent way to do a handout.” The distribution quickly turned chaotic, and Abu Gharbeh watched as children in the front of the crowd would collect their shoes, then run to the back to sell them to people who couldn’t fight their way in. A few days later, walking through the camp, he saw dozens of the shoes for sale in the central marketplace. “It was a symbol of how the whole system worked—or didn’t work,” he said.

The question of what to do about these malefactors wore on Shishakly and other members of the international-aid community. Several people who worked at the camp told me that if such a thing could have been enforced, many of the residents might have been made to go home—their towns were safe, and they were staying only because of the reliable flow of aid, or for personal enrichment. Abu Gharbeh estimates that only a quarter of the refugees in Atmeh genuinely need the services and sanctuary it provides, but that nothing can be done about it. “If we stopped funding the camp, maybe sixty or seventy percent of them would simply go home,” he said. “The other twenty-five percent would die.”

As Shishakly stepped up his involvement in the camp, he also gradually increased how much authority he exercised, but by the spring of 2013 his approach had begun to backfire. At the time, things had been looking up. Resources were flowing steadily from Turkey, and there were close to a dozen projects being undertaken by a number of international relief organizations. The Turkish Red Crescent provided daily breakfasts. International Medical Corps had started digging sewage canals and was helping to run the pharmacy. Barada, a private nonprofit run by a Syrian-German woman, helped build a school. The Syrian American Medical Society ran a dentist’s office. An Egyptian activist raised money for a pediatrician and donated prescription drugs. A French NGO performed a census. During this time, Abu Gharbeh told me, Shishakly “had some real power, because he was doing a lot of work, and there were results.”

Meanwhile, some of the most important jobs at the camp were being handled by people who lived there permanently. Shishakly had encouraged the section leaders to work together with various other figures of authority, including FSA commanders and businessmen from Atmeh town, to create an internal administrative committee, to make decisions and adjudicate disputes. One of those figures, a local businessman, had started up his own kitchen, and was using it to prepare uncooked breakfast packages that were delivered by a Turkish NGO.

But Shishakly had always been anxious about the lack of oversight among the NGOs. He’d seen resources squandered or stolen, and he suspected that some of the local businessmen were stealing portions of the breakfasts and selling them on the side. Early in his time in Atmeh, Turkish officials had placed Shishakly in charge of the humanitarian border crossing at Atmeh, meaning that every food item or other aid package entering the camp would have to be approved by Shishakly personally, no matter which agency or individual was importing it, or where it was going. When he saw an agency operating in a dishonest way, he would delay or even block their shipments, sometimes forcing NGOs to stop working at the camp altogether.

The move worked a little too well. Faced with a loss of control over their imports, businessmen and middlemen fought back. According to Shishakly, the local businessman who’d opened a kitchen made a brusque adjustment when Shishakly interfered: He stopped cooking the food, and told the refugees that it was Shishakly’s fault. “He said to us, basically, you want to be the manager, then you do the cooking,” Shishakly recalled. “Of course, he knew what he was doing—he was trying to make the people hate us. He told everybody that we were trying to stop their food from being prepared.”

At another point, Shishakly said he noticed that an agency from the Gulf had suddenly appeared at the camp, working with yet another local businessman from Atmeh to construct a bakery. Shishakly didn’t recognize the agency. What’s more, he says, large portions of flour supposedly intended for the bakery kept disappearing. So he blocked a shipment. In response, the agency, like the breakfast cook, shuttered the bakery, infuriating the residents of the camp, who took their frustration out on Shishakly.

“Everybody was so mad at me,” Shishakly said. He showed up at the camp the next day to find residents chanting angrily outside the Maram office. As he walked up, the mob noticed him and turned. “You stopped the bread! How could you!” he remembers them screaming. Shishakly was taken aback. “Are you crazy?” he replied. “I’ve come here only to work for you—why would I stop the bread?” Eventually, he says, he placated the crowd, convincing them that he had nothing to do with the bakery’s shutdown.

But as the year wore on, it became clear that complaints like these were reverberating through the camp. Abu Gharbeh recalled a time in the spring when donated food ended up stuck in a warehouse in Reyhanli for so long that it spoiled. “The people at the camp were growing angry at Maram,” he said, “because all they were hearing were promises. They felt the reason for the delays was because of Yakzan.”

Fifty years ago, journalist Patrick Seale published The Struggle for Syria, a gripping account of the chaotic decade after the 1943 end of French occupation. Shishakly’s grandfather, Adib Shishakly, came to power during this time, providing political and economic stability, but ending his four-year term with an upheaval that would set the tone for Syria’s modern tumult.

The ramifications of the turmoil that preceded Shishakly’s time in power—much of it supported or instigated by him—cast a heavy shadow over his tenure. By the summer of 1949, the year Shishakly took control, there had already been two coups. In the second, Shishakly had conspired with a pair of military officials, including a popular officer named Sami al-Hinnawi, to depose the country’s then-president, Col. Husni al-Za’im. The takeover was quick and bloody: Awakened in the middle of the night, al-Za’im and his prime minister, Muhsin al-Barazi, were hustled outside in their pajamas, subjected to a rapid tribunal, and shot on the spot.

Under Hinnawi, Shishakly was placed in charge of the Army’s powerful First Brigade. This new alliance managed to last an impressive four months before Shishakly’s disaffection with his old friend—and concerns about the direction of the country—led him to seize power himself. In the early hours of December 19, Shishakly sent tanks into Damascus, making his the third coup in a year. Hinnawi, unlike his predecessors, was not sentenced to die; instead, he was sent into exile in Beirut, where he was assassinated less than a year later by the cousin of al-Barazi, the executed former prime minister.

Shishakly ruled as a populist, promising to uplift peasants to a position of greater prominence in Syria. Historians credit him with some of the earliest attempts to correct the country’s gross economic disparities and the overwhelming primacy of a handful of families, which had become a substantial burden on Syrian society. In Hama province, for instance, just three families—the Barazis, the Azms, and the Kaylanis—owned a preponderance of land across the northern countryside, including ninety-one of 113 villages. “They really lorded it over them,” Joshua Landis, a political analyst and historian of Syria at the University of Oklahoma, says of the treatment of the working class by the Syrian landed gentry. “They would ride around on horseback and swat at the poor people with whips. It was very feudal.” In 1951, Shishakly helped motivate a three-day anti-feudalist demonstration in Aleppo, the first of its kind in the Arab world. “He had a vision for a more egalitarian Syria,” said Landis, “where they would get rid of these cruel landowners who were tyrannizing the people.”

But Shishakly’s agenda was also slipping from its populist ideal into something more nefarious and despotic. Faced with threats to his rule and discontent over his strong-armed economic policies, he began to make more decisions unilaterally. He extended state authority into the far reaches of daily life, urging the government takeover of public schools, abolishing political parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood, and embarking on a brutal military conquest of the minority Druze sect. He also “imposed order by building a police state,” according to the historian Andrew Rathmell. In upending the feudal system, and introducing the political ideologies of economic balance and peasant power, some historians argue, Shishakly set Syria on a course that would lead directly to the rise of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, and, ultimately, the family of Bashar Assad. “He started Syria down that road of socialism and land reform and punishing the feudal masters,” Landis says. “It was the first skin of the onion.” When, in 1951, the parliament made an attempt to veto Shishakly’s policies, he simply had it dissolved and positioned himself as the country’s sole authority with executive power. In a presidential election two years later, Shishakly won with a distinctly Assad-like 99.7 percent of the votes.

The Shishakly era came to a close in 1954, when he, like his predecessors, was ousted through a military mutiny—a tenure animated by lofty aims and expansive vision ending in betrayal and disappointment. He eventually retired in Brazil, where, a decade later, he was assassinated by a disaffected member of the Druze community.

As I read this history, I couldn’t help but wonder about Yakzan’s own accidental rise to a position of authority. The brothers both strongly contest the notion that their grandfather was a dictator, even one with an egalitarian vision. In his history, Patrick Seale suggests that the elder Shishakly’s accumulation of executive powers during his tenure was more a product of necessity than wanton ambition. This ambiguous legacy has stuck with many of the people who accompanied the brothers in the contemporary effort against Bashar Assad.

“People remember both sides of history,” Lina Attar told me. “Some remember the great leader and others recall the military strongman. Many Syrians were disappointed in the years after Adib Shishakly’s rule, especially after the Ba’ath Party takeover.” She added, “I remember people were wary of rallying around the Shishakly family when the younger Adib first became politically prominent at the beginning of the revolution. Syrians either love the elder Adib or they hate him.”

Not even Yakzan’s harshest critics accuse him of anything like the autocracy of his grandfather. In fact, just the opposite: They often cite his insistent optimism and his stubborn determination to singlehandedly improve the lot of those in Atmeh as the characteristics that most impeded him at the camp. “The problem with Yakzan is that he was trying to carry five apples in one hand,” said Omar Bakkour. “He was bringing in supporters to show them the camp, he was taking their money, and he wanted to be in charge of doing everything—and it was a hard job.”

Of course, the problems at Atmeh were much larger than any one man, just like the problems in the uprising were larger than just Atmeh. One fascinating component of reading about Syria’s history in the 1940s and ’50s was noticing how many of the last names—and lingering family conflicts—ricocheted across the modern-day opposition. Of the many Syrian expatriates with whom Shishakly regularly came in contact were several descendants of people his grandfather had tangled with sixty years ago. The grandson of Muhsin al-Barazi, who was killed in the coup partly orchestrated by the elder Shishakly, now runs an agency similar to Yakzan’s, delivering aid from southern Turkey to distant, rebel-held parts of Syria. The granddaughter of Sami Hinnawi, who Yakzan’s grandfather ousted in the later coup, is an interpreter for the UN in Turkey. Even the head of the Syrian opposition’s humanitarian-affairs wing, Suheir Atassi, has ties to the old days: Her ancestors led the opposition against the elder Shishakly in the final years of his reign, and one of them mounted the mutiny that ended his rule. In public, the descendants talk about the feuds as bygone history, but at least one I met quietly described another family as a “nemesis.” Historical betrayals are not so easily forgotten. “I guess my dad killed his grandfather,” another descendent said when we met in southern Turkey. “But we could also ask him why his grandfather killed my cousin.”

For the Syrian opposition, these sorts of historical tensions have only compounded the troubles of an already delicate alliance, which has struggled from the start of the uprising to cohere into something more than just a shared antipathy toward Assad. The fracturing of the opposition—from the top political committees all the way down to the fighters on the ground and humanitarian workers in the field—was one of the primary sources of the uprising’s eventual stalemate. Activists and politicians bickered with one another in conference rooms in Doha and on the planning committees in Gaziantep. In late 2012, the opposition coalition, viewed as too divided and out of touch, was completely dismantled and replaced with another one, this one supposedly less closely affiliated with supporters of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. More recently, Atassi, who held posts in both the humanitarian affairs bureau and the political opposition, was forced to resign from the latter after she was accused of mismanaging funds and bringing politics into relief operations. (She has denied the claims.)

Meanwhile, in places like Atmeh, the return of well-heeled expatriates with last names like Shishakly poses a different kind of challenge: They may not be wholly embraced by an opposition looking to move the country forward. “The Sunnis in charge of the fight today are not the well-heeled educated Sunnis coming from abroad,” says Landis. “The fight now is being led by the rural, urban lower class. And they don’t want those people to come back. There is an urban-rural divide and there has always been and in some ways the Shishaklys and Hinnawis, they were an expression of the revolt of the middle class against the urban notables. No one wants them back.”

Early in the summer of 2013, Shishakly was still making expansive plans for Atmeh. He’d recently helped create a special program for children, which he described as a kind of refugee summer camp. It included games and art classes but also therapy and dental clinics—and he hoped to make it a full-time affair. “It’s a pilot project,” he told a reporter at the time. “We’re planning to do this camp inside all the camps in Syria—and not only the camps, even inside the cities and villages.” The situation at Atmeh, he said, was “better than in other parts of the country.”

But on the ground, the obstacles facing Shishakly were only mounting. That summer marked a second year of merciless heat, with attendant disease and unrest. (“In the summer, people get too bored,” he told me. “So there are more problems.”) Meanwhile, his tactics in the winter and spring had proven costly—attempting to control the camp had turned competitors into foes while antagonizing potential allies. He had few friends he could count on when refugees criticized his work, or when his missteps were inflated through rumors of malfeasance.

At some point that summer, Shishakly recalled, a television network did a report on the camp that contained a litany of complaints about Shishakly and the rest of the management. He was dismayed. “I know at that time that the kitchen was working at full capacity, that every tent was getting their bread daily,” he said. “But what could I say? I had to control myself. I said, ‘Look, we have no security, we’re trying our best, but it’s not enough.’ I was not happy.”

Even so, it wasn’t easy for him to leave the camp, and it took threats to his life to actually drive him away. The kidnapping, as it turned out, was just one manifestation of this danger. Through the summer, Shishakly says, he was continuously reminded that he risked his life with each visit to Atmeh. “I used to walk between the tents by myself all the time,” he said. “But later I had people really loyal to me at the camp, and they would say, ‘Why are you going by yourself? We’ll keep you company.’ I pretended I didn’t know, but I did: They were coming with me just to protect me.” In the end, he couldn’t even trust those people. That September, Maram turned over administration of Atmeh to the camp’s internal committee, leaving just a handful of employees to manage its remaining projects.

These days, Shishakly prefers to view his shortcomings at Atmeh as primarily a matter of resources: If he’d had more money, he could have taken responsibility for much more, could have done much more. “It’s about creating order,” he told me when we spoke by phone this past July. “You have to have things in order, and in order to put things in order you have to have money. You have to pay salaries, you have to build infrastructure. And we never had that.”

Maram’s orphanage in Reyhanli had just opened, after months of preparations and negotiations. He was thrilled, and, once again, intensely busy. “I’m so proud. I just love it,” he said. “I’m spending every day there. We can finally control how we raise these children—we can do it in a Syrian way. I consider it like my home.” The orphanage will eventually care for 100 children.

Yakzan’s experiences in Atmeh were a harsh lesson in the limits of what he could control—and, in a way, in what could be achieved through the Arab Spring itself. An entire generation of young activists had invested themselves in a similar dream, embracing the promise of a Middle Eastern awakening, imagining they could help their country obtain noble things—freedom, community, integrity. And they let themselves believe that their good intentions were all it took. The fall has been as disappointing as the rise was hopeful. “Yakzan kind of got into something that was much bigger than he expected,” Attar says. “And I think that happened to all of us. In a way, Yakzan’s story is very similar to the story of the uprising; our ideal expectations versus the human reality. The arc of events that happened to Syria, Atmeh was a microcosm of that.”

The closest I ever got to Atmeh came in the fall of 2013. At the time, ISIS, which already controlled large parcels of northeastern Syria, had recently begun to advance on the western Turkish front, and the area was under grave threat. There were reports that inside the camp itself, Islamic militias had made themselves a dominant presence: Women had to wear head coverings, and visits from the outside had all but ceased. Still, the Free Syrian Army was nominally in control of the border entrance point, and the gate between Turkey and Atmeh remained open for humanitarian crossings and medical emergencies.

The system for handling emergencies inside Atmeh was well-rehearsed: If someone at the camp fell seriously ill and couldn’t be treated at a local clinic, they would be permitted through the border and transported to the main hospital in Reyhanli. A network of Syrian and Turkish doctors, working under the auspices of the quasi-governmental Turkish aid group IHH, had crafted a sophisticated network for funneling patients—few of whom had passports or other documentation—between hospitals that could treat their various ailments. Most of the patients would eventually be returned to Atmeh.

For the delicate border transfer itself, the Turks relied on a handful of Turkish ambulance drivers whom they trusted to pass back and forth across the border without paperwork or security checks. One afternoon, I hopped into the cab of an ambulance driven by a man I’ll call Mohammed. Since the start of the war, Mohammed had volunteered nearly every hour of his day, and many sleepless nights, to transporting the sick and injured between Syria and Turkey. The fuel for the ambulance was supplied by a charity, and he received no compensation for his work. (Two camp officials described him as dedicated and scrupulous. “He’s better than any of the Syrians,” one said.) Mohammed carried two phones, and they rang incessantly. “Most people who work with me, they make it about a month before they quit,” he said as he hastily ate a chicken sandwich. “There are no days off in this job.”

One of his phones rang. It was a border guard informing him that a woman had fallen ill and needed to be delivered to Reyhanli. He put the ambulance into gear, and we turned down a gravel road in the direction of Syria. We passed through a small Turkish farming town, driving along a shallow creek that served as one of the Syrian war’s main smuggling routes. We eventually arrived at a rudimentary checkpoint, where we were stopped by two Turkish border guards smoking cigarettes near a rusted iron gate. The guards glanced at Mohammed as he pulled up, then casually waved him through. Up a winding path, in the shadow of a heavily armed Turkish border tower, we came to a waist-high stretch of barbed wire and rusted pilings, and a small gate guarded by bearded and bedraggled FSA fighters, their uniforms half assembled, Kalashnikov rifles slung over their shoulders.

Mohammed jumped out of the cab and warmly greeted the guards before collecting his patients. I stayed in the vehicle and looked around. Near the entranceway, children swarmed in a burst of frenetic energy. Other refugees loitered close by, watching. A few of them tugged at Mohammed’s shirt, pleading with him to bring something on his next trip, or ferry a few more people to the hospital. (He took two more patients than he’d meant to.) Beyond them, I could see a muddy, sloping hill and a chaotic array of white and blue tents, their tattered roofs disappearing into the horizon. For a moment, I could picture what Shishakly must have seen when he approached the beginnings of this camp, with all its disorder under the groves, and imagined that the path to fixing it, to giving something back to Syria, was right there in front of him.

2 Comments

Many thanks for this wonderful story, Joshua. Moving and emblematic. There is too little of this sort of reporting. In the 1980s I interviewed Jamal al-Atassi, a leading early Baathist from the famous Hom family. Atassi worked for the overthrow of Adib Shishakli in 1954, but told be that he regretted it. He said that in retrospect it was clear that Adib Shishakli was working toward many of the things that the Baath was calling for. He believed that Shishakli may have avoided many of the excesses of the Baath. Atassi was undoubtedly right. Many Syrians would have perfered the relatively benign dictatorship of Shishaki to that of Assad.

All the same, Shishakli's effort to subdue the Jabal Druze by force, killing scores of innocent people, precipitated the revolt that caused his downfall. His violent subjugation of the Druze also motivated Nawaf Ghazaleh to seek revenge for his parents who were both killed by Shishakli during the bombardment of Jabal Druze. He hunted Shishakli down in Bazil ten years later and shot him. Violence has a way of begetting ever more violence.

Another interesting parallel with Syria today is that the revolt against Shishakli began in the North of Syria and gathered momentum there until Aleppo, Deir ez-Zor, and Hama had unified in opposition to Damascus. The militiary of the North threatened to march on the South. Rather than stay and fight, possibly dragging his country into a bloody civil war, Shishakli boarded an airplane and flew off to exile in Saudi Arabia and eventually Brazil. Although he spared Syria civil war, the country remained politically divided and unstable.

Thank you for this added and valuable context, Joshua. It's such a fascinating period of Syrian history.

I'll only add the rather striking detail (and further possible parallel with today) of what Shishakly is reported to have said, when he was faced with that revolt from the north: "My enemies are like a serpent: the head is the Jebel Druze, the stomach Homs, and the tail Aleppo. If I crush the head, the serpent will die."