The nation of Azerbaijan, wedged into the Caucasus Mountains between Russia and Iran, is small, geopolitically vulnerable, and relatively new to the contrivance of nationhood. Most of its history has been spent on the fringes of someone else’s empire; millennia of successive imperial occupations ended with the crumbling of the Soviet Union, and, over the twenty-five years since, Azerbaijanis have been experimenting with novel forms of national pride. Their patriotic boasts have the tentative feel of an audition: Locals like to try out the claim, for example, that within their borders one might find no fewer than nine different climates, as if to suggest a surprising capaciousness. One of the nine, and by far the most important, is the dominant natural ecosystem of the Absheron Peninsula, home to the Azerbaijani capital of Baku. The peninsula holds almost half of the nation’s 9 million people and, though it accounts for only 4 percent of the country’s mass, produces more than 80 percent of the nation’s industrial output. The Absheron biome, rich in oil and natural gas and their apparatuses of removal, might be described as one of the Earth’s great hellscapes: Tracts of its ground are permanently on fire; shallow black pools of crude oil seep through contusions in the sand; small volcanoes disgorge bubbles of cold, thick mud, whose slow rivulets peter out across the plains of barren rock. But this variegated purgatory is the chief reason for Baku’s astounding wealth. Some cities come into prominence at the confluence of great rivers, in the safety of generous harbors, or by their nearness to wheat. Others are planted by political fiat. Baku has come into its own extractively.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the hellscape was just steps from downtown. It basically was downtown, at first. Then it was the entire peninsula. The whole region, potted haphazardly with genuflecting derricks, was greasy and dangerous. Where there weren’t derricks, ambitious men dug their own claims, cladding with planks the sidings of what often turned out to be their graves. The whole thing was fast, dirty, and improvised—and successful. By the turn of the twentieth century, Baku had become the world’s energy capital, producing more oil in 1900 than the United States. By 1913 the city was producing 95 percent of Russian oil, which was 55 percent of the global total.

The parts of Baku that were neither pocked nor on fire, however, were made over during the city’s rise in wonderfully eclectic (if often kitschy) extravagance by the oil-born nouveau riche. Magnates erected manors in no particular style—or, more accurately, a terrific profusion of them—using limestone quarried from the high crescent of ridge that overlooks the city. Polish architects were hired to study revivalist vernaculars, then proceeded to build the new city in a pleasing spirit of incoherent ambition: Art Nouveau, Venetian and French Gothic, Italian Renaissance, German Baroque, here or there a house after the fashion of a dragon or an upright deck of cards. The buildings’ only commonality was their architectural derangement, their vague Europeanness, and their hue of toast.

There was little in the way of historic authority to invoke. For more than a thousand years it was a walled warren of a few anxious souls on the southern rim of a peninsula open to invasion from the Caspian Sea. It only ever came into relevant existence as a place operated on the basis of the borrowed, stolen, extracted, or rashly erected. Baku ultimately became a national capital by default: The most important ancient centers of the Azeri people were Derbent to the north (now in Russian Dagestan) and Tabriz to the south (in Azeri Iran). Incoherence has always been its medium. The thing is, the first time around it worked. Foreigners arrived and planted in this austere place a kaleidoscopic metropolis; it was billed as “Paris on the Caspian.” It may have been just steps from the wasteland, but that was the price of development ex nihilo. The upshot was a driven cosmopolitanism, a community of diverse immigrants united by the opportunity to get in on the fiery ground floor of a new city.

For seven decades following World War I, the Soviets imposed a lull of order on this chaotic and resource-rich Eurasian outpost. The foreigners drawn by the oil boom had stayed, and the special cosmopolitanism persisted. The independent post-Soviet city is again full of foreign fortune-seekers, kept mostly well-behaved by a smiling, mustachioed autocrat, but the old cosmopolitan order has given way to the internationally minded larks of an ahistorical petro-state. The presiding statue of Kirov—an early Politburo member and thus a symbol of the old regime—has been torn down and replaced with a trio of blue towers (condo, hotel, business center) in the shape of bulky flames. These are the most visible symbol of Baku’s construction hysteria, overseen by a regulatory apparatus so byzantine, the lines of oversight so tangled and corrupt, that—as practically no one will admit in public and everyone will in private—developers simply build first and bribe later. The evidence is in the streets: More than 500 new high-rises, each less interesting than the next, went up in the first five years of the twenty-first century, and though the pace of construction has slowed somewhat since, men still weld and hammer at all hours.

Now the older neighborhoods of low-slung one- and two-story homes in the Persian style, their courtyards Tetris-stacked with generations of informal additions, are being razed en masse, and the city is being fitted with ever more obelisks of blue and taupe glass. Bakuvians whose families have lived in the city’s center for generations have been removed to the distant margins for the sake of spacious showrooms for imported handbags, the ground level of the belle epoque mansions now transformed into storefronts for Tom Ford, Celine, Dior, Ferragamo. The old industrial hell has been relocated as well—a few miles down the road, just beyond the first turn in the highway.

The hope in all this has been that the successful model of the first oil boom might be recreated. This time they call it “Dubai on the Caspian.” The new efforts, however, recall not particular places but the international reign of placelessness—Shanghai’s Pudong, or the old port of Buenos Aires, or the City of London. The biggest difference between the first boom and this most recent one is that by the time the second one happened, the city already existed; the irony is that its cosmopolitans—the Jews and the Armenians and the Russians—had all departed, and those who’ve remained have been sold a strange mix of recent nativism and international glitz. If we give them a panorama of futuristic radiance, the thinking has been, they won’t mind that they weren’t consulted, or that none of it makes sense. They will be united at the end of the Earth by the new global city.

Incoherence and improvisation was also our mode. I’d arrived in Baku with Joshua Cohen, a friend and novelist, who’d been dispatched to Azerbaijan to report on a small community of mountain Jews who’d been living for hundreds of years near the border with Russian Dagestan, who spoke their own quasi-Persian language and had produced almost half a dozen post-Soviet oligarchs. One of them was serving as an official in the World Jewish Congress. Cohen wanted to see who these people were and how they’d all gotten so rich.

Our flight approached through a searing sunrise over the Kazakh shores of the Caspian, but when we landed it was somehow still dark. Heydar Aliyev Airport arrayed itself below us in several stories of beige trays underneath a reinforced glass shrinkwrap. The air felt vacuumed and over-oxygenated.

Within minutes we were in a taxi racing along the empty fourteen-lane highway that led to the city center. The idea behind this artery is that one day it will resemble Sheikh Zayed Avenue in Dubai, where incoming traffic is impressed by a row of skyscrapers, each more Promethean than the next. Only a few towers had been built along the middle stretch of the avenue, most of them empty, the light of sunrise passing untrammeled through their facades. One blue tower resembled a large droplet on a throne. This was the state water company. Nearby, another tower in identical blue glass looked a lot like a torch, and was either the headquarters of the state bank or the state oil company—or both, depending on whom we asked. There followed a whole series of edifices that, like the Strip in Vegas, had taken recognizable architectural forms—in this case, baroque palazzi—and bloated them to totalitarian proportions, a whole neighborhood of Bellagios.

The new grandeur gave way to the old one as we passed the House of Government, a wedding-cake pile in the late Stalinist style, its cornices ornamented with sumptuous wing-dings and its front yard a scale Tiananmen, and swerved into the twelve lanes of Oil Workers’ Avenue, a lakefront highway that separated the city from the Bulvar, the broad seaside promenade that extended from the walled city toward the old port. Older women in orange vests bent down to sweep the early morning streets with short brooms; whole companies of uniformed men monitored demolition projects, smoking cigarettes and leaning against stacks of marble curbs. In front of us, on the ridge that subtends the city, rose the three Flame Towers. Stylized fire is the city’s symbolic stock in trade—various small fires have adorned the city’s shield since the nineteenth century—and the Flame Towers are supposed to resemble the tongues of some great conflagration. In their stolidity and molded bulk, however, they look more like giant penguins straining toward an impossible dream of flight.

Once the cabbie dropped us off at our hotel, we immediately set out in search of some historical bedrock. We toured the labyrinth of the old city, most of which had, in fact, been built only a hundred years ago. In the alleys, men hawked carpets woven with the face of the president and faux-karakul hats woven from recycled plastic bottles. Almost all of the buildings were anchored with large bas-relief bronze plaques commemorating someone who was born or lived or spent ten minutes there once; it seemed an effort to tie the buildings to something other than the names of the streets, which had been changed from Azeri and Western names to Russian names and then back to Azeri names once more.

This shouldn’t have come as a surprise. In the weeks leading up to our departure, I’d gotten e-mails from well-wishers describing Baku as a “difficult,” “frustrating,” “messed-up,” “fucked-up” place. Friends of friends told me their best contacts there were in prison or exile. The government had recently jailed its most visible journalist dissident. Even the guidebook relied on hand-sketched maps drawn to no identifiable scale. Whenever the maps were wrong—as they were in the book, on the internet, on our phones—someone, predictably, blamed it on the streets. Authorities hadn’t even bothered to keep the house numbers constant. Azeri websites, if they existed, weren’t updated, or they directed you to cell-phone numbers with either too many or not enough digits. On the side of every building was a CCTV camera, many of them visibly disconnected. There was no graffiti anywhere, nor homeless people, nor buskers. Every third person was a security guard. Most of the museums were open by appointment only.

With the exception of an early Christian state called “Albania” and a brief period of peaceful Georgian rule in the twelfth century, the history of Azerbaijan is the story of how a group of loosely organized khanates along a minor spur of the Silk Road did their best to fend off routine imperial incursions. The Baku khanate, a semiarid, derelict station with a wide harbor, was known as a particularly unfortunate place to water your camel—both because there was very little water and because the peninsula, lit up to passing ships by its various scattered ground fires, was extremely difficult to defend. In 1806, the Russians subjugated the khanate, which by then was just a beleaguered port city of a few thousand people.

It was over the next seventy years, in the lead-up to the first oil boom, that Baku began to acquire its peculiar character. In 1828, Russia signed a treaty with the Persians, dividing Azerbaijan in half at the Araxes River, which from then on would be seen as Europe’s border with Asia; Baku is thus a European city, even though it’s east of Baghdad. It was, by all accounts, a miserable frontier. One scholar quotes an 1840s travelogue of Alexandre Dumas, who described Baku as little more than “a place where tigers, jackals, panthers, snakes and poisonous snakes roamed freely.”

Then, in 1848, the world’s first industrial drilling operation went online. (It is a continuing point of pride for the Azeris that the second, in 1849, was in Pennsylvania.) For the next twenty-five years, the tsarist regime allowed only two-year contracts on the land, which inspired a short-term free-for-all but did little to secure infrastructure or investment. The bona fide commercial boom would have to wait for the denationalization of Azerbaijani oil, in 1872. The Swedish-Russian Nobels—brothers of Alfred and until then arms manufacturers—and the Rothschilds showed up that decade to build the first refineries, build the first laked-in tankers, and construct a Transcaucasian railway to the Black Sea port at Batumi. Over the next thirty years or so, Baku saw the arrival of the French, the Belgians, the British, the Germans, the Poles, and increasing numbers of Armenians in flight from Ottoman persecution. The city’s population swelled from 14,000 to 210,000. Actual Azeris—often disparagingly referred to as Tatars, or Turkic Muslims (a historically inaccurate term)—became a tiny minority, though a handful of them happened to make a fortune and become local philanthropists. Meanwhile, Russian was the lingua franca.

Only some of the foreign barons put nontrivial effort into the well-being of their workers—the Nobel brothers provided free education and housing to their employees, and introduced an innovative profit-sharing plan—but for the most part conditions were dreadful. Visitors strove to outdo one another in the dreariness of their descriptions. One 1905 arrival wrote, “Baku, considering its immense wealth, is one of the worst managed cities in the world.” Another visitor compared the boomtown to the industry of Pittsburgh carried out under the lawlessness of Dodge City superimposed on the gated orientalist treachery of Baghdad. Essad Bey, the German Jew who went on to become the pseudonymous author of the great Azeri national novel, wrote that the saying among Russian businessmen is that “whoever lives a year among the oil owners of Baku can never again be civilized.”

The combination of appalling working conditions, an international proletariat, overnight wealth, and great distance from Moscow made Baku the “revolutionary hotbed on the Caspian”—an appealing site both for socialist agitation (Stalin put in a few years there) and for the machinations of agents provocateurs. For some twenty months after the end of the First World War, the local powers were able to block out for themselves the world’s first Muslim parliamentary republic. But the area was simply too important strategically—as both an energy producer and a buffer against the colonial spheres of influence in the Middle East—for the Russians to give up, and in 1921 it was incorporated into the Soviet Union.

There is a famous filmstrip in which Hitler is presented with a birthday cake in the shape of the Caspian; he drizzles crude, in the form of chocolate sauce, on a slice marked Baku, and lifts it to his mouth. He subsequently declared that without the oil of Baku—which was fueling the Soviet war effort—the war would be lost. Anticipating Hitler’s success, Stalin had concrete poured into many of Baku’s wells. Rather than going through Turkey, however, Hitler pressed south through Stalingrad—in part because of the symbolic value of the name—and never reached the Caspian installations.

After the war, Soviet resources went into the development of offshore fields. The most famous of these was built at a place called Oily Rocks, about twenty miles southeast of the peninsula, where an entire settlement was put up on stilts (and, partially, on the sunk Nobel tanker the Zoroaster), complete with hundreds of miles of roads and apartment blocks for thousands of workers. (Oily Rocks continues to produce some 5 percent of Baku’s oil, though thanks to an unflattering Austrian documentary it’s now practically impossible to visit.) For the most part, however, the Soviets felt that Baku was still too fragile to remain the empire’s largest energy producer, so the bulk of oil production was removed to new fields in Siberia.

Older Bakuvians, particularly those skeptical of the recent changes wrought by the second oil boom, remember Soviet Baku with great fondness. The Russians controlled the makeup of the urban class, and the city was heavily settled by Russophone academics and engineers. Soviet internationalism only reinforced the image of Baku as a cosmopolitan place, with a genteel mix of Russians, Armenians, Jews, and a minority of Azeris. Baku was far from Moscow in distance and far from the rest of Azerbaijan in feeling and manners, so its citizens enjoyed a kind of island isolation, developing a reputation for Eurasian courtyard camaraderie and inclusive good fellowship, on the one hand, and, on the other, a level of sophistication—in theater and in what was supposedly the best jazz in the Soviet Union—that made other Soviet cities look like backwaters. Locals were accustomed to a nightly passeggiata along the Bulvar, and in the leafy, dappled crosshatch of nineteenth-century streets around Fountain Square.

The fall of the Soviet Union saw two radical transformations of the city take place in parallel. The first was the result of an irredentist war with Russian-sponsored Armenia in the mountainous province of Nagorno-Karabakh; as a result, 300,000 Armenians were expelled from Baku, and the city in turn took in twice as many internally displaced persons from territories now occupied by the Armenian and Russian armies. With the mass departure of the Jews for Israel and America, and the repatriation of many of the city’s Russians, in less than a decade Baku was transformed from minority Azeri to more than 90 percent local. It was the first time in 200 years—which is to say pretty much ever—that Baku was actually an Azeri place. The arrival of the Karabakh refugees, along with streams of economic migrants from the underdeveloped Azerbaijani countryside, inspired widespread resentment on the part of refined Bakuvians; in the new arrivals they saw people who brought cows into their houses and spat sunflower seeds on the swept granite expanses of the Bulvar. (The city’s elite still send their children to be educated at Russian schools, though they fear their daughters will inherit loose Russian morals.) As one person put it to me, “There’s an old saying that after fifteen years the village man becomes the city man. But if enough village men come to the city, after fifteen years the city becomes the village.”

The second great transformation was the redevelopment of the oil industry. In 1994, after brokering a cease-fire with Armenia over Karabakh, President Heydar Aliyev (a former KGB general) signed the “contract of the century” with seven foreign oil companies; he was seen as a hero for his successful resistance of overtures for an exclusive arrangement with the United States. The major impediment to successful exploitation, however, was the lack of an export channel, and it wasn’t until 2006—when the Ceyhan pipeline, through Georgia to Turkey, was completed—that the second oil boom came into full sway. Europe could now get oil and gas that had the advantage of being both non-Russian and non-Saudi, and Baku got the money to transform itself from the Paris on the Caspian to the Dubai on the Caspian. Between 2003 and 2008, according to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the GDP per capita went up fivefold, from under $1,000 per person to approximately $5,000, just one perk of what had become the second fastest growing economy in the world.

One of the few intellectuals recommended to us as a possible source of reliable information—mostly because he was neither in prison nor in exile—was an urban theorist at a new private university, one that had apparently been built to facilitate the education of the president’s son. He was an administrator with a glass-fronted office that overlooked a small party of idle secretaries, his walls adorned with foreign degrees and a poster of the various waves of Mongol invasions. He brought us tea and little packages of Turkish Delight. Hospitality, he explained, was at the center of the Azeri self-image. “You can arrive at my home with under your arm the severed head of my son,” he said, “and still I will treat you like a guest.”

The theorist didn’t seem to be particularly concerned about government brutality—the harassment and imprisonment of journalists in particular—and in fact it seemed to him that fears about the government, and resentment for its heavy hand, had been overstated. “As long as you apologize and promise not to do it again, they will let you out of jail.” Still, out of caution, I will call him Yadigar.

“There’s no other city with oil inside it,” he said, pointing out the window to the campus. It looked like the new science and engineering quad at Stanford; they had landscaped away the dust, planted young conifers in a grid, laid down sod like a tarp, and outlawed smoking. If you smoked, a sign warned, you would be added to the list of undesirables. But places like this campus were new, and Yadigar was accustomed to being able to point out the window at a nodding derrick. “It was desert. No water. Nothing existed here. Who’d want to come over here?”

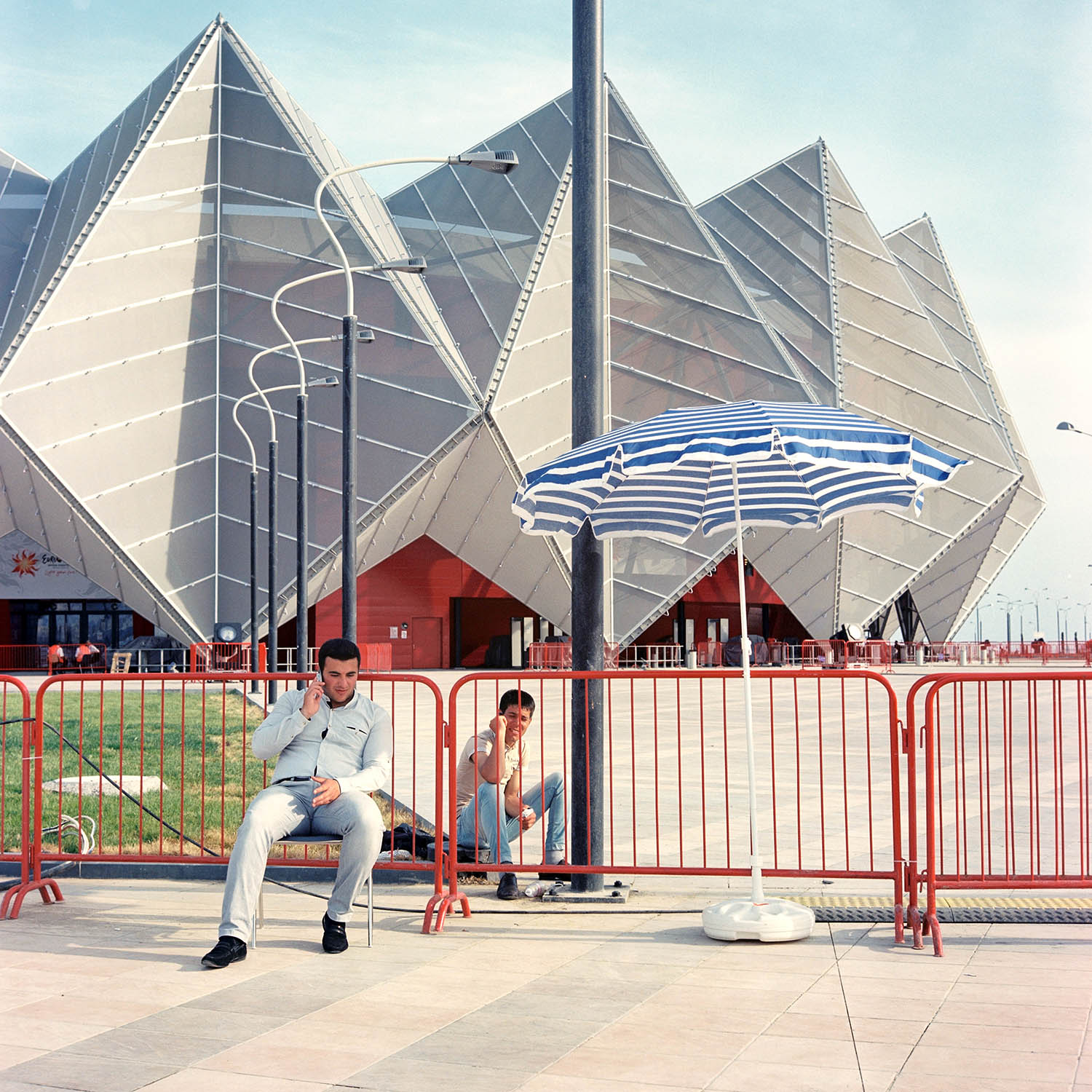

Well, you came for the oil, and with the money from the oil you built upward from the desert. “If you look at the architecture you see the whole history here. You have ancient, medieval, tsarist, baroque, Soviet, all on the same street. We had the Constructivist style, and then the Khrushchevki, the cheap tower blocks built all over the Soviet Union. Now we have the new style, the wave style, like the Heydar Aliyev Center. It’s a masterpiece, it’s beautiful, but it’s not functional. It’s a convention center with four museums. Why build that?”

He put out some chocolate and leaned back in his chair. “The idea of the government is to show off,” he said. “Azeris understand perfectly well that none of this is real. There’s that beautiful building in the form of a large water drop, the state company for water delivery. That cost $100 million—and there are villages that have no water.” In the estimation of one local urbanist, more than 50 percent of contemporary Bakuvians live in informal dwelling places unconnected to the utility grids; there aren’t any better alternatives in a city where the average two-bedroom apartment has become as expensive as it would be in Prague or Berlin. “All along the road to the airport, the poverty and the dilapidated buildings have been put behind walls, so they can force you to believe it’s like Dubai. The skyscrapers are just symbols. It’s architecture porn, to show off. It’s just being able to say you have the tallest building in the Caucasus. We are sheikhs, and this is the sheikh mentality.”

These sheikhs, however, are Europeans. “If you want to insult an Azeri,” he said, “call him Asian. Now that we have all of these glassy things, we feel we are part of Europe. We squandered all of our money on these tall buildings so the poor Georgians would come and say, ‘Wow!’ Europe is considered from the perspective of progress, technology, innovation, cleanliness. Europe is the thing we are trying to reach. It is an impression that is entirely visual—no honking, no screaming, no spitting in the street. That is the visualization of Europe in Azerbaijan.”

So Azeris know what they want from Europe: its cleanliness, maybe its absence of corruption, and a greater role for the rule of law. But as Yadigar explained it, there is still no connection with cultural liberalism. Azeri culture continues to be very conservative, though they take pains to call it secular-traditionalist instead of Islamic, and they’ve been happy to leave much of what they find in Europe—gays, women behind the wheels of cars, freedom of the press—safely in Europe. There is also “no connection with democracy. We can have law with a king as long as it’s a good king.”

In the early days of the boom, people felt they had a good king. Heydar Aliyev, the current president’s father, had become the patriarch of modern Azerbaijan after saving the nation from from being swallowed up once more in history by Russia or Iran. Most of the important buildings and streets in Baku are named after him, or at the very least relatives of his. There’s the Heydar Aliyev Airport, of course, and the Heydar Aliyev Mosque, and then there’s the Heydar Aliyev Center, which was designed by a Turkish subaltern of Zaha Hadid. From the air, it supposedly looks like Heydar Aliyev’s signature. From the ground, it looks like a pile of frozen burial shrouds.

A friend of a friend introduced us to an Azeri named Firzuli, who took us to see all of the Aliyev buildings, beginning with the Heydar Aliyev Mosque. Built in a late, leaden, bottom-heavy Turkish style, it is the largest mosque in the Caucasus, completed in only four months at a cost, people estimate, of hundreds of millions of dollars. It rises in the omnipresent limestone from a graded piazza that could comfortably hold 50,000 people. The front colonnade is buttressed by long escalators.

Firzuli parked near a low chain cordon. On the grassy square was a marble sculpture of a huge open book, engraved with deep gold lettering. From a distance we assumed it had to be a Quran, but up close it was actually a spreadsheet of the building’s staggering dimensions. There wasn’t a single worshipper in sight. A policeman told us that it wasn’t actually a functional mosque, that it never would be. He pointed to three houses on a rise, and explained that the residents of those three houses had complained that the call to prayer bothered them, so the government decided to keep the mosque shuttered.

We asked Firzuli if this made any sense to him. “Yes, of course,” he said. “Those people complained, so now there is no muezzin.” He shrugged. To him this was just one more gigantic building constructed in haste and at great expense to show off. In this way it was exactly like most of the hotels, apartment buildings, and offices in the city. There was nothing special about this one save the minarets. If the hotels were practically empty, Firzuli said, why should the mosques be any different?

The Heydar Aliyev Mosque is just one more artifact of the principle that if you build something grand enough, it doesn’t matter if it ever actually works. In this case, the audience to be appeased was an Islamic one. Rather than engage with traditionalists in a debate over headscarves in schools, it was much simpler—if more short-sighted and costly—to signal your theoretical regard for Islam with the construction of a building big enough that it can be seen from anywhere.

The Flame Towers play the same role for a secular crowd. At night they cycle through an LED extravaganza: Their exteriors scroll alternately with animated flames, sparkling water, and a white silhouette waving an Azeri flag twice its size. Bakuvians remember the nineties, when power was intermittent and the streets were dark; now the city at night is dizzy with light.

For this streetscape and its light were the Azeri wager on the future. The Soviet identity—the internationalism and sophistication—was irretrievable. There was no strong national identity to speak of; people from the villages were more attached to the tribal identities of the old khanates than they were to some specious reinvention. There was a powerful sense of pan-Caucasianism—in the dances, in the prodigious, indigestible portions of peasant mutton plov, in the sense of rugged hospitality—but that raised the problem of archenemy Armenia, and it wasn’t, in any case, enough to underwrite a nation.

Firzuli had wanted to go out to a club, but he was in his sixth month of unemployment and the drinks were expensive. He’d had a good job at a bank before the recent slowdown and currency devaluation; now he couldn’t find anything. He’d attempted to open a little café where kids could come and play PlayStation, but so many policemen had hit him up for bribes that he couldn’t afford to keep the lights on. The only way to avoid the bribes was to have a family connection, and he had no family. So, instead of taking us out on the town, he invited us to go play video monopoly at a men’s club with some of his friends, the cheapest way he could pass the time.

As we sat down to the video monopoly screen, Firzuli told us a story: His family, in Soviet times, had had a small store with a few meters of frontage on Fountain Square. After independence, a mafioso came to his grandfather and told him it was time to sell the store, and gave him a price for it—maybe a tenth of its value at best. His grandfather had no choice but to accept the offer. The mafioso took over the store and was soon killed by another mafioso, who wanted the store for himself. Within a few months that second mafioso was killed by a third mafioso.

“And then,” Cohen asked, “that third mafioso was killed by a fourth mafioso?”

“No,” Firzuli said. “The government came and took it.”

“What about the mafia?” Cohen asked.

“There is no mafia. There’s just the government.”

We began to play video monopoly. Cohen is from Atlantic City and was keen to show our Azeri friends his home street, but when he looked down he discovered London. The men played with grim determination for the stakes of tea. Firzuli got up to go to the bathroom and his friend began to cheat as quickly as he could, auctioning off properties and trading the better of Firzuli’s holdings for the poorer of his own. He encouraged us to get in on the theft, but we sat there too stunned by the feverish pace of his cheating to say anything at all. Firzuli came back and saw the condition of the board before him. He saw the muted frenzy in his friend’s eyes. His friend relentlessly pressed his early and ill-got advantage. After he won we all put in our manats to play another game.

“We have a saying in Azeri,” Firzuli said. “We say, ‘You can wake up a man who is sleeping, but you cannot wake up a man who is only pretending to sleep.’”

In Baku all metaphors fell apart because even the cynical truths were often lies. Firzuli had taken us to Ateshgah, the old putatively Zoroastrian temple near the first oil fields that had been built as an altar around an ancient and perpetual ground fire. The story, he told us, was that in the 1870s the neighboring kerosene facility had tapped into the temple’s gas reservoir, and within a year the eternal flame had been extinguished. It was a sad story and Firzuli told it with some hard-won weariness. In truth, the temple’s last “priest” had sold off the rights to the field in 1879. By 1881 they were piping in gas for the eternal flame for the pleasure of the region’s first tourists.

What people kept telling us was that things could be much worse, and the fact is that Bakuvians still feel as though they have something to lose. The government hasn’t stolen quite all of the money. People can still get good jobs on the offshore rigs—fifteen days on, fifteen days off for the very good salary of about $2,000 a month—though we were also told that without family connections it costs at least $20,000 in bribes to line up a job from which one might be fired at any moment. Still, as Yadigar said, “It’s not like this is Angola.”

Toward the end of our trip, Firzuli drove us out of town on the western extension of Oil Workers’ Avenue. We told him we wanted to see Qobustan, one of the premier sites for Azerbaijan’s paleolithic petroglyphs, and the location of what were apparently the best mud volcanoes. We didn’t expect much from the petroglyphs, which were bound to be as rudimentary and inexplicable as petroglyphs anywhere, and the mud volcanoes were something we felt obligated to take in. The tourist sites of Qobustan were really just a pretext to see where the dislocated industry had been reestablished—where, in other words, things hadn’t been papered over with glass.

On the way out of town, we stopped at the National Flag Square, a large plinth supporting an Azerbaijani flag almost invariably unfurled in one of the Caspian’s incessant winds. The flag, which flies on a pole more than 500 feet high, was designed by an American, and upon completion in 2010 it was recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest flag in the world. The entire project, including the plinth, reportedly cost $24 million. We stood in the windswept parking lot, alone but for the little black police boxes, like modular Kaabas, that oversee all public spaces in Baku.

National Flag Square represented the triumphal marking off of the resplendent city from zones of industrial entropy. Just beyond the square was another large, empty mosque, followed by rings of sprawl that eventually gave way to a harsh arid sienna of dust, stone, and mud. The buildings that rose off the desert plain on either side of the highway were bleak: refineries crowned with abrupt discharges of controlled flame, cement works with their lashed-together towers of rusted gray, endless limestone-shelled barracks for the workers in the plants and on the offshore rigs. Everything was punctuated by rusty derricks. Everywhere the earth was scarred, trenched, and intubated; hoses and ducts bent into high trellises, then came together into what looked like toppled pipe organs before they separated again. The land looked like it was on a vibrant final charge of extensive life support. It was hard to see it as anything but the last moment of a civilization right before a precipitous descent into its Mad Max phase.

We had to bribe a cop to take us up to the plateau with the mud volcanoes. The ground around us churned and gurgled with cold, sludgy indigestion, which eventually dried into elaborate craquelure; we could pick up the smooth, ragged-edged pieces like dinner plates. The dry plain to the sea was spread about below us, dark and scabrous, cut and channeled and exploited with bent impromptu conduits. It was a landscape swollen and distended with waste-heat, an entropic pit.

I turned to Firzuli. “Does anyone care that this looks like this? We’re only what, like twenty or thirty kilometers from the Four Seasons?”

“This is the deal,” he said, his words uninflected. “As long as Baku is clean, everything else can be ugly.”

The Azerbaijani people were being given the new Baku as the great national symbol. Even those who could never afford to live there were expected to accept its cleanliness, its modernity, and its ambition as the heart of the national project. If the older Bakuvians, the ones who were so nostalgic for the café-glaces and open-courtyard, sea-promenade esprit de corps of Soviet times, feel frustrated and betrayed by post-Soviet Baku, it’s not just because of the bumpkin arrivistes or even, really, the open government plunder; it’s because the cosmopolitanism that had meant so much to them—that had justified their habituation of this disorderly tearoom on a grimy peninsula on the far-flung brink of the empire—has now been pressed into the bland service of international commercial overcapacity. Eventually the whole country would balance itself out into two zones: endless neighborhoods of the poor living cheek by jowl amid waste-heaps and industry on the one hand, and, on the other, glass-and-steel Baku, with its broom-swept streets and sea-side promenade.

And the deal with the people on both sides will be this: At least we’re not Angola; at least we’re not Kazakhstan; look up at all the buildings! Even now, the bus-stop billboards that advertise a city to itself portray it as a tidy if crowded island, replete with architectural fantasy, on a gleaming, unrippled, landlocked sea.