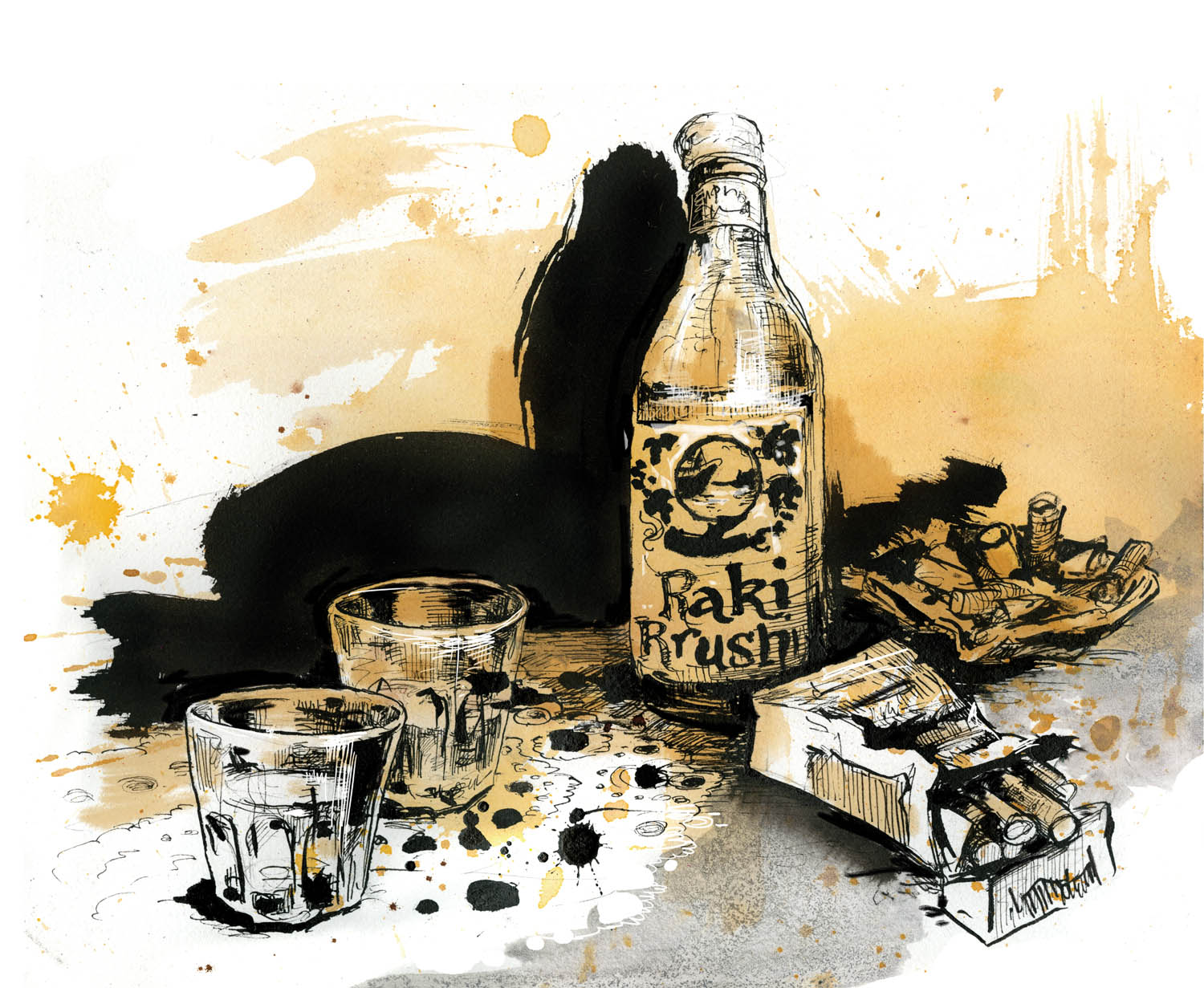

One of the first things I learned in Albania is that when a stranger pours rakia—a sweet brandy typically distilled from grapes or sugar plums and served cold in a short, sweating glass—you drink it, promptly and with vigor, regardless of whether you are already swallowing back a hot snake of vomit, or if it is barely nine o’clock on a Tuesday morning, or if it was poured from an unmarked plastic water bottle stored under the sink amid graying jugs of bleach, or, especially, if the person who has offered it is simultaneously recounting how, a few years back, he got angry and shot a man. Such is the custom here: You honor your host’s hospitality. You honor everything.

I had flown to the Balkans in late July 2017 to learn about blood feuds, or the ancient oaths of vendetta sworn between warring families and passed on from one generation to the next. The killing is concentrated in northern Albania—in the rural, often unreachable villages of the Accursed Mountains, and in the modern city of Shkodër, one of the oldest municipalities in southeastern Europe. Here, justice works like this: When a man is murdered, his family avenges his death by similarly executing either the killer himself or a male member of his clan. Sometimes, after a killing has been successfully vindicated, the feud is settled. Other times, the head of the family that initiated the feud, while admitting both sides are now ostensibly “equal,” nonetheless chooses to perpetuate the cycle by killing a second male from the avenging family. “In this way the feud might rage backwards and forwards for years or even generations, each family being in turn murderer and victim, hunter and hunted,” the Scottish anthropologist and ethnographer Margaret Hasluck writes in The Unwritten Law of Albania, one of the first accounts of the customary law of the Albanian highlands.

Guns remain the primary means of blood-taking here, in part because guns are relatively easy to come by in Albania. Reports estimate between 600,000 and 650,000—though maybe twice that—were looted from military stockpiles in the late 1990s, after the Albanian government unlocked its weapons depots in the midst of what seemed like inevitable civil war (“Guns were the first thing we went for, then flour for bread,” Aleksander Marleci, a local politician in Shkodër, told Politico in 2016). When I asked my young translator, Elvis Nabolli, how hard it was to get a weapon in Albania these days, he laughed and laughed. “You want a gun? You can have a gun.”

Nabolli had helped me arrange a meeting in Shkodër with Nikollë Shullani, a large, kind man who volunteers as a missionary for a nongovernmental organization called the Committee of Nationwide Reconciliation. Shullani attempts to negotiate peace between combative factions. To hear him explain it, the job sounded impossible. It is certainly treacherous. Blood feud missionaries are often threatened with kidnapping or torture (in 2004, one of Shullani’s colleagues, Emin Spahija, was murdered outside his home in Shkodër; the case remains unsolved). Shullani prefers to approach families on religious holidays—it’s an opportune time, he said, to remind them that the Catholic Church considers wrath a cardinal sin, and that the Quran says never to “kill a soul that God has made sacrosanct, save lawfully”—and will reiterate the punishments they’ll face from the state (twenty-five years to life in prison, if caught). Still, it’s not an easy thing to get anyone to agree to. To forgive an attacker—even one who has been convicted and served a full sentence in prison—is shameful. It humiliates your family and dishonors the memory of your lost relative. This creates a second kind of loss: “A man slow to kill his enemy was thought ‘disgraced’ and was described as ‘low class’ and ‘bad,’ ” Hasluck explains. “Among the highlanders he risked finding that other men had contemptuously come to sleep with his wife, and his daughter could not marry into a ‘good’ family.”

Though it’s almost impossible to substantiate the statistics, aid organizations estimate that at least 12,000 Albanians have been murdered for blood in the last twenty-five years. It’s hard to convey the particular tenor of life as the object of a feud, the relentless, pervasive anxiety, the clenching. There’s no relief. In Blood Revenge, the anthropologist Christopher Boehm recounts how, for Montenegrins involved in a blood dispute with an Albanian tribesman, the preferred mode of execution for the Albanians was “to creep up onto the house and climb onto the roof. They would remove a shingle, and then would kill their victim where he slept, at short range.”

Per ancient edicts, the avenging family should hunt only an able-bodied adult male (the elderly, women, or boys who are too young to carry arms are excluded), though in recent years those dictums have relaxed, and it is no longer unusual to hear about the retaliatory murder of a young boy or girl. Feuds can begin over most anything, though a high percentage seem to involve property disputes. Despite earnest intervention by the church and the government, reconciliation between feuding families is rarely (if ever) brokered without blood, and the object of a feud—and his family members—are forced to spend decades barricaded inside their homes, hiding. To venture beyond the property line could mean a forceful and immediate death: sudden bullets from on high. Children are pulled from school; jobs are lost. Untethered from the rhythms of a regular life, and unable to conceive of a peaceful future, people drift into depression. Life is at once terrifying and terrifically boring. Families rely on donations to survive. Maybe friends bring food, boxes of groceries. Everyone watches a lot of television. Suicide is not unheard of.

The morning of our first meeting, Shullani, who wears a gold ring and carries a leather folder of documents at all times (I still don’t know what these papers said or did, only that I never saw him without them), offered to introduce me to a man I’ll refer to as Joseph, who’d been embroiled in a blood feud since 2002. This required traveling to Joseph’s home on the edge of the city, where he now spends all his days and nights.

Driving there, down a long dirt road, it looked like inland Cuba, only more faded, less tropical: piles of stone, fences on top of fences, drooping power lines, loose dogs without all their fur. Joseph’s home was strategically situated at the very end of the road, surrounded on all sides by a six-foot cement cinderblock wall. Once a person had bounced all the way down there, there was really nowhere else to go, or at least not quickly. To leave would require slowly backing out the same way you came in.

Shullani approached the house first, while I waited outside in Nabolli’s red Fiat. Nabolli was a reporter himself—a broadcast journalist and writer who had recently been awarded a prestigious Balkan Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence for his work on cannabis farming in the Accursed Mountains. (Nabolli’s father, who owns a bar in Shkodër, is a lifelong Elvis Presley fan; in 1986, he paid off a handful of Communist Party officials in order to give his son Presley’s name). Nabolli, like almost everyone I met in Albania, owned several different models of cell phone that all rang more or less constantly. He got especially excited when talking about his true passion, investigative journalism. In the e-mails we exchanged prior to my trip, he assuaged my anxieties by repeatedly insisting, “It’s okay!” each time I introduced a fresh concern. I would eventually take up his words as a kind of mantra.

Soon, Shullani reappeared and ushered us out of the car and through an ornate gate. The Committee of Nationwide Reconciliation, like many of the NGOs dedicated to mediating blood feuds in Albania, has been investigated for issuing false certificates—papers declaring that the holder’s life was in grave and imminent danger—to help unemployed Albanians get asylum (and a job) elsewhere in Europe. In 2013, Nicholas Cannon, Britain’s ambassador to Albania, warned of “a business in so-called blood feud certificates,” and suggested that the certificates “should not in general be regarded as reliable evidence of the existence of a feud.” The con here, if there is one, is difficult to track: It’s possible that the EU is balking at the prospect of absorbing more refugees into what’s already an overtaxed system, or that enterprising Albanians are taking unfair advantage of a potential way out of a desiccated economy. In general, the veracity of a certificate is impossible to determine without an expensive and time-consuming investigation.

Joseph’s front yard was filled with a curious array of detritus: a wheelbarrow containing a great number of watermelon rinds, plastic barrels, bits of unidentifiable machinery. The exterior of the house was painted baby blue; a tidy front porch contained several potted plants. He appeared and welcomed us inside.

There was a large flat-screen television in one corner of the room. I sat on the couch, in front of a coffee table decorated with two ceramic swans and a heavy crystal ashtray. I turned my recorder on and put it down, tentatively. Joseph placed a glass of rakia in front of each of us. He wore jeans and a gray polo shirt. His eyes were an icy, intoxicating gray; he seemed calm, nearly nonchalant. Joseph, who is fifty, had previously served in an elite squadron of the Albanian armed forces—the Special Operations Battalion, which features a dagger in the center of its logo, along with the word “Komando.” He passed me a cell phone, on which he’d called up a photo of himself dressed in uniform, his pants cinched high by a belt sagging with ammunition. Fifteen years ago, he had gotten into some kind of heated altercation with a fellow solider. Somebody no one liked, he said—somebody who was always causing trouble, running his mouth. They fought; he was insulted. He raised his gun and killed him. This was followed by an arrest, a trial, and a prison sentence of eighteen years, of which he ultimately served eight. Now released, he is embroiled in a feud with his victim’s family, which remains intent on killing either him or one of his two sons. Shullani has not yet had any luck brokering a détente.

Despite believing these feuds to be barbaric and philosophically flawed—savage by any Western standard—I wondered if the blood feud was also the purest distillation of justice as practiced by a modern society, the least complicated restoration of some essential psychic balance. Blood let for blood let. By any accounting, it was a cathartic reckoning, to avenge a crime properly. It surely facilitated a particular kind of healing. Besides, what did it mean to witness and absorb something wicked, but not to correct for it yourself? Intellectually, I understood it was a mark of maturation and empathy and civilization to defer justice to a court, to some impartial entity separate from the family. But I thought, too, of the political philosopher Michael J. Sandel and his book Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? “The conviction that justice involves virtue as well as choice runs deep,” Sandel writes. Was justice not, at heart and freed from any attendant subtext, simply a faithful restoration of equity?

Vengeance is not merely prevalent in rural enclaves here; the notion of vigilante justice is threaded into Albanian culture. In 2015, Armando Prenga, a Socialist lawmaker and an elected member of Parliament, was arrested after getting into a barroom scrap with a sixty-six-year-old fisherman named Tom Cali. When members of Cali’s family went to local police to report the incident—Cali had been badly pistol-whipped—Prenga burst into the station with his brother and a cabal of associates, discharging several rounds of gunfire and hollering, “We will eradicate your tribe!”

“They don’t want any deal,” Shullani said now. “They don’t want to discuss these topics. They said, ‘Even if we live for a hundred years we won’t let it go because we want revenge. He killed the best guy in our family.’ ”

When I asked Joseph if he was scared, he shrugged, gave me a look like, “Eh.” Mostly he worried after his children, who are now twenty-three and twenty-five. His own life seemed unimportant to him.

“I don’t know how it will happen,” he said. “So, I hide here and I wait. I take some measures but no one knows how it will happen. I’m just waiting.”

Even with the rakia warming my belly, I was still having a difficult time understanding what it might feel like to live that way—to wait around to die, violently. And not to wait in the vague, imprecise way that we’re all waiting around to die—not in the way where you never quite believe that it will happen to you, or to the people you love the most, but to know that it will, any old day now. To truly absorb it as part of your daily philosophy. To exist in a siege state marked only by deep monotony and a hysterical anxiety for your family.

“Do you regret it?” I finally asked. Nabolli repeated the question in Albanian. Joseph responded quickly.

“No,” he said. I could tell he found the question ridiculous. “I was insulted. I worry only for my children.”

Anyone planning to visit northern Albania should expect several chaotic or mystifying encounters—incidents that can’t ever be fully accounted for. In my experience, these range from funny to fully harrowing. Driving across the border from Montenegro, I handed my American passport and insurance card to a guard, who guffawed, refused to look at it, and then dismissively waved me through (when I left Albania, I waited at the border crossing for several hot, worrying hours in order to show my documents to a Montenegrin officer; during this time, my rented Volkswagen was surrounded on several occasions by gaunt gypsies in wheelchairs, who banged endlessly on its windows). If you are traveling by car, expect other motorists to periodically come barreling directly toward you, tearing down the wrong side of an intermittently maintained road (driving is a fairly new pastime here; prior to the fall of Communism, there were hardly any cars in Albania, and most people moved about by bicycle or mule-cart). While digging around online for travel tips, I uncovered an apparently viable suggestion for how to catch a bus to the Lake Koman Ferry—a boat trip famed for its breathtaking views of the gorges surrounding the Koman reservoir, and infamous for how many people and animals cram aboard—that involved arriving in the city center “before 6 a.m.” and yelling “Koman!” At dinner on my first night in Shkodër, at a cafe on Bulevardi Skënderbeu, the pedestrian thoroughfare that runs through the center of the city, I was eating a plate of tavë krapi, or carp baked in tomatoes, when power to the street suddenly went out. Everyone snickered, then continued on with their business, now in total darkness. Nabolli reiterated a kind of survivalist mentality on occasion, usually immediately after something weird happened: “Balkans!” he would say, and shrug. “It’s okay!”

Though Albania has been suggested as Europe’s next big tourist attraction for years—the New York Times placed the Albanian coast at number four on its list of “52 Places to Go in 2014,” claiming, “this is Europe when it was fresh and cheap”—it remains off the tourism radar, meaning the truly breathtaking countryside just outside of Shkodër is still largely unspoiled. Theth National Park, about fifty miles northeast of the city, has become a coveted destination for intrepid European backpackers and climbers, though the road to Thethi, the small village that acts as a gateway to the park, requires several river crossings and is often impassable, even in a well-equipped off-road vehicle. (Nabolli showed me a promotional video that Land Rover filmed there in 2014; the subtitles read, strangely if perhaps not inaccurately, “Nobody you know has been here.”) Thethi itself is known for its ancient and foreboding lock-in tower, or kullë, a hugely fortified stone structure with a single tiny, rectangular window. Families engaged in a blood feud would send their men to a kullë to await retribution (the window was to accommodate the barrel of a sniper’s gun). Closer to Shkodër itself, it’s possible to visit historic properties—like Mes Bridge, a stone archway built by the local Ottoman pasha in 1770 to connect Shkodër with the city of Drisht, or Rozafa Castle, a mysterious but imposing fortress of Venetian origin—without encountering a single gift shop or ticket taker or tour guide. The structures merely remain.

The Albanian language—shqip—is spoken almost exclusively here (it is also used, on occasion, in Kosovo, Macedonia, and parts of Montenegro and Serbia), and though it’s believed to be derived from the language of the Illyrians, the Indo-European tribes who occupied the Balkans beginning in at least the fourth century b.c., it effectively resembles no other European languages. The Albanian alphabet has thirty-six letters, and words are riddled with double consonants, which means, for an English speaker, it can feel phonetically inscrutable. I know a modest amount of Serbo-Croatian—mostly vernacular phrases I learned from my father, the first-generation son of Croatian immigrants who never spoke much English. Yet I still inhaled sharply each time I tried to say even the most inane things, like “Ukuˆgaan iˆxamnakuˆx,” or “Nice to see you.” My pronunciation was often so demented that halfway through I’d sheepishly cover my own mouth with both hands. David Pryce-Jones, in his essay “The twilight of Zog,” called Albanian “a language apart,” suggesting its “linguistic mystery holds its speakers together but stands in the way of outsiders.” It is in this way that it most suits its country.

“Six people were killed,” Nabolli said. We had picked up Shullani again, and were driving to visit with another family living on the ramshackle outskirts of Shkodër. For almost twenty years, they had been involved in an especially gruesome and absurd feud. “Okay, the guy who makes three kills—in 2000, he was working in the other village, with the other family,” Nabolli explained, pausing only to shift the Fiat. “He was working, and after the work, the other family said, ‘Come in to eat something.’ So he comes in to eat something. And they said, ‘With rakia.’ And he said, ‘Thank you, but I don’t want rakia, I don’t drink rakia, I want only to eat and for you to give me my money.’ And they said, ‘No, you are in my house, you need to drink rakia.’ He said, ‘No, I don’t want rakia, I just want to eat and go back to my house.’ And they said, ‘No, you have to drink rakia.’ And they take the pistol, and they say, ‘If you don’t drink rakia, I will kill you. And so he said, ‘Okay, I will drink this rakia, but you will have problem with me.’ And after, he goes to his house, gets his gun, and then one day later, he kills the person who gives the rakia. After this, the other family, they want to take blood feud, and so they kill two brothers of the guy who made the first kill. And the guy returns, to make other kills. After they kill his brothers, he went to live in the mountains. And the other family lived in the village, near Tirana, the capital. He knows in what place they live. He go there, and he stay for a lot of days, just looking at where they live. One night, he goes inside the house, where there are all the mens. And he killed two of them, and injures three others. Five people were shooting. After this, he returns to the mountain. Two killed, three in the hospital. The special forces came and killed him. This is the story. For rakia.” He paused. “Never say no to rakia!”

Twenty minutes later, seated on a couch across from six framed photos of the family’s dead (handsome men, and tall, with serious eyes) I was handed a cup of rakia by a woman in a dark red blouse, the sister-in-law of the man who, seventeen years ago, had denied another family’s drink. They refused to acknowledge or concede his death, which would end the feud, because it had come at the hands of the police—not one of their own. She told me, with Nabolli translating, that her sister had recently killed herself; she feared too much for the inevitably grim future of her young son. Now, this woman and her own son—he appeared around twenty-five; he was wearing a faded black T-shirt with a peace sign on it—were hiding out in a tiny rental home, near a stretch of nonfunctioning train tracks.

Once shock at the sheer brutality of a feud had dissipated, what ended up lingering, for me, was how numbingly static they all felt—I could ping question after question about the circumstances of a dispute, or the various avenues for reconciliation, or the strange rituals of living with a bounty on your head, but ultimately the facts were plain and unchanging. The certainty of it was nearly hypnotic.

I understood then that a feud did not facilitate justice but merely reiterated pain, ad infinitum. “The real aim of every story is a justification,” William Gass writes in Tests of Time. I tilted my head back. I drained my glass.

In 2011, Hinter Records released a compilation of traditional Albanian folk songs and improvisations, recorded in the 1920s and ’30s and remastered from the original 78 rpm records, called Don’t Trust Your Neighbors. The title itself is a fairly concise encapsulation of the Balkan temperament (the album art features a map of Albania and the countries that surround it; each one is identified only as “Neighbor”), but the songs—careening, mesmeric dirges, as intoxicating as they are disorienting—convey something pure about both Albania’s devotion to its traditions and its metaphysical constitution. These melodies, which are usually played on clarinet, are devious, wary, quick-footed. It can sometimes feel as if they are carrying a knife.

Death-for-death is not an uncommon system of justice in other places—including, of course, parts of the United States—but it is generally only applied when preceded by a trial and a guilty verdict, itself an evocation of some written and legislated law. The Albanian government discourages and punishes murder, but, as with any criminal-justice system, the process is flawed; given the nation’s history of unstable and deeply corrupt rule, it isn’t particularly surprising that rural Albanians distrust the courts, or that the resolution of a feud feels too deeply personal to offload elsewhere.

I’ll hedge here and say that, in late 2017, trying to establish a condensed but legible geopolitical history of the Balkans is nearly impossible. At various points in its history, its lands have resembled a jigsaw puzzle forcibly squashed into place. Albania, in particular, has a knotty and Daedalean past. The University of Texas presently manages the Perry-Castañeda Collection of Historical Maps of the Balkans, many if not most of which indicate territorial strife, and bear titles like “Contested Regions” or “Territorial Modifications” or, my favorite, “Balkan Aspirations.”

Yet some awareness of the region’s history feels essential to understanding the curious and singular nature of Albanian national identity, which is the result of endless colonizations, conversions, and spiritual subjugations. Even familial history is unreliable here: If you were born into a certain faith or political persuasion, it would be difficult to accurately discern whether those ideals were forced upon your ancestors by invading regiments or arrived at by choice. It would be hard to know who you were or what your people believed.

The Kingdom of Albania was declared in 1271, by Charles of Anjou, a French count and Crusader who wrested the territory from the Byzantine Empire. (Charles’s cousin, Helen of Anjou, established thirty Catholic churches and monasteries in his kingdom, though there are believed to have been Christian families living in Durrës, a port city on the Adriatic, as early as the time of the apostles.) The Serbians took over for a brief while—from approximately 1343 to 1355—but by 1431, Albania, like most of southeast and central Europe, had fallen under Ottoman rule. Young men, some only eight or ten years old, were often swept up in “child gatherings,” wherein Christian boys were yanked from their villages, converted to Islam, and enlisted in the Janissaries, the elite infantry units of the Ottoman army. Some Orthodox and Catholic Albanians fled to southern Italy to evade conversion, where they became known as the Arbëreshë (centuries later, Franciscan priests, descended from Arbëreshë émigrés, would return to northern Albania to re-establish Catholic parishes there).

Resistance toward the Ottomans started as early as 1432, but it wasn’t until 1912 that insurgent forces, galvanized by the Albanian National Awakening that began some thirty years earlier, were able to capture the city of Skopje. The Treaty of Bucharest, signed in 1913, established an independent Albanian territory. The next half century was complicated, even by Balkan standards: There was a short-lived Principality of Albania (1914–1925), an Albanian Republic (1925–1928), a monarchy (1928–1939), an Italian occupation prior to World War II, and then, finally, the Socialist People’s Republic of Albania (1946–1992), a Communist state run by Enver Hoxha, a hardline Stalinist dictator who declared Albania the world’s first atheist nation. “The religion of the Albanian is Albanianism,” Hoxha repeated, citing Pashko Vasa, a nineteenth-century poet, and previously an instrumental figure in the National Awakening.

The nation turned godless—at least outwardly. I think of the opening stanza of “The Mystery of Prayers,” by the Albanian poet Luljeta Lleshanaku:

In my family

prayers were said secretly,

softly, murmured through sore noses

beneath blankets,

a sigh before and a sigh after

thin and sterile as a bandage.

People withdrew, got quiet. Hoxha demanded unflinching national pride and unity, and cultivated a stunning isolation from the rest of the world, cutting relations with the Soviet Union, China, and every other Communist regime. This resulted in an economic crisis and a degree of self-sequestration that makes present-day North Korea look equal parts coherent and inviting. Private ownership of goods (besides housing) was banned. Citizens paid no taxes. After Hoxha died, in 1985, his successor was overthrown and, in 1992 the Democratic Party won a national election, though the transition was neither smooth nor honorable. In 1997, the new government—corrupt, compromised, rebellious—collapsed. The economy was again undone, now by a series of Ponzi schemes—many endorsed by the Democratic Party, as fronts for arms trafficking—which ultimately cost Albanian citizens around $1.2 billion. For a while, at the end of the 1990s, the country was subsumed by anarchy.

In 1998, Albania ratified a fresh constitution, reestablishing a democratic government dependent on the rule of law. A few weeks before I arrived, Albania held its ninth democratic election, re-electing Edi Rama—the former mayor of Tirana, the nation’s capital, and a member of the Socialist Party—to a second term as prime minister. How the country might continue to evolve under Rama’s leadership remains unclear. In 2015, he supported the creation of a commission tasked with opening and collating the long-secret files of the Sigurimi, Albania’s ruthless, murderous state police under Hoxha and, per the Times, “vetting candidates for public office to see if they collaborated with the repressive machinery of the former Communist regime.” As of my visit, this work had not yet begun; many believe files were destroyed as a matter of routine. Others are skeptical of Rama’s intentions with the information. Fatos Lubonja, who spent seventeen years in an Albanian gulag after the Sigurimi discovered his diary during a raid (in it, he was critical of Hoxha) told the Times he believes that Rama is opening the files strategically, and only when they can be used as “weapons of blackmail to attack opponents as collaborators, or to cast supporters as sympathetic victims.”

Albania’s official borders have always been arbitrary and problematic; ethnic Albanians who found themselves on the wrong side of new national lines were either rendered impalpable or aggressively persecuted. The Kosovo War, which started in earnest in the 1990s after the Serbian President Slobodan Miloševic´ began a horrific ethnic cleansing campaign that resulted in the deaths of thousands of ethnic Albanians living in Kosovo, is a particularly jarring example. The war was both prompted and escalated by the Kosovo Liberation Army, or KLA, an Albanian paramilitary terrorist organization with alleged ties to Osama Bin Laden, that fought against Yugoslav security forces. Even now, there are still worried mumblings of ISIS recruitment centers thriving in Albania, trading on the ill will engendered by the endless oppression, torture, and banishment of Muslims in the Balkans. (Before my trip, I wrote to an old high school friend, a global-risk professional who had served for several years in the US Army and has a particular knowledge of the Balkans, for advice. “What I can tell you in broad strokes is that Jihadi sympathy is rising in the area. With any luck you might just spot the ISIS flag being flown in the open,” he wrote. “As far as advice goes, when you touch down get a decent knife and keep it on you.”)

Today the Albanian diaspora is vast: Per the 2011 census, there were roughly 2.8 million Albanians living in Albania proper and 1.6 million in Kosovo. The countries of Greece, Macedonia, Italy, and Turkey each hold half a million Albanians, which means that considerably more ethnic Albanians live and work abroad than in-country. According to the Migration Policy Institute, a Washington-based think tank, Albania still has the highest migration flow in Europe. “One-third of the population has left the country in the last 25 years,” their 2015 report states. Ergo, Albania continues to feel less like a plot of land and more like some abstract, not-quite-realized idea: a ghost empire.

In her book High Albania, Edith Durham—the daughter of a distinguished British surgeon, who first sailed to Albania in 1908 at the age of forty-five—drubs through the Accursed Mountains in a waterproof Burberry skirt and Scotch-plaid golf cape, determined to “give the national points of view, the aims and aspirations, the manners and customs” of the Albanians, as she had done in her previous writings on Serbia and Macedonia. According to her biographer, Marcus Tanner, Durham was born into a “self-consciously progressive mid-Victorian family,” and when its matriarch, Mary Durham, eventually required full-time caretaking, Edith, who was unmarried and childless, reluctantly assumed the job. “The future stretched before me as endless years of grey monotony, and escape seemed hopeless,” she later wrote. After five years, Durham lost it. She acquired a doctor’s note dictating that she be allowed to spend two months each year abroad. She chose the Balkans, sailing first to Montenegro, in the spring of 1900.

In his introduction, John Hodgson wrote of the resistance Durham surely endured prior to her departure: “Every sober counsel would have warned against it,” he writes. “There was little reliable information about the Albanian highlanders; the mountain tribes had maintained their separate identities for centuries, sullen to a Turkish government that had never won more than nominal suzerainty over their wild expanses of inhospitable rock.”

A century later, her book remains one of the most objective and colorful narratives of the region (a central thoroughfare in Shkodër, Rruga Edith Durham, is named for her). In Blood Revenge, Boehm describes the lurid—if not quite inaccurate—nature of most nineteenth-century Balkan travel narratives: “From travelers’ reports, it seemed as though the traditional Montenegrins were doing almost nothing else but sneaking up on each other and firing from ambush.” Durham seems to approach the Albanians she meets with compassion if not total approval. In the book’s best bits, she reports with empathy, and doesn’t disparage or editorialize foreign customs. She simply records them.

Durham was particularly transfixed by blood feuds (in 1909, a reviewer for the Daily News suggested that her book “literally reeks of blood…Miss Durham seems to share [the Albanians’] exultation in the glory of man-slaying”) and is careful to distinguish the realization of a blood feud from common homicide. “Blood-vengeance, slaying a man according to the laws of honour, must not be confused with murder. Murder starts a blood feud,” she writes. Later, she advises against moral judgment: “It is the fashion among journalists and others to talk of the ‘lawless Albanians’; but there is perhaps no other people in Europe so much under the tyranny of laws.”

In 1446, a nobleman named Lekë Dukagjini succeeded his father, Prince Pal Dukagjini, as ruler of Gjilan, one of seven districts of modern-day Kosovo. Details of his reign are scant: He fought against the Ottomans, and ambushed and murdered another prince, Lekë Zaharia Altisferi, following a humiliating altercation over the hand of a woman. Dukagjini is mostly remembered for the eponymous Code of Lekë Dukagjini, or the Kanun, a set of traditional Albanian laws and rules of conduct, which was primarily spoken until the twentieth century, when it was first transcribed into text.

In High Albania, Durham suggests that the Kanun predates Dukagjini by millennia, having been established during the Bronze Age; other scholars consider it even older, pre-Homeric, a derivation of ancient Illyrian tribal laws. Some believe it was based on Dušan’s Code, a comparable set of ruling principles established by Stefan Uroš IV Dušan, the King of Serbia, in 1349. Dukagjini almost certainly did not devise or even perfect these statutes, though he was known and admired for his honor and sense of justice. But he was, at least, among the first Albanians to institutionalize and codify them.

The Kanun has twelve sections: Church; Family; Marriage; House, Livestock, and Property; Work; Transfer of Property; Spoken Word; Honor; Damages; Law Regarding Crimes; Judicial Law; and Exemptions and Exceptions. Within those twelve categories are 1,262 articles, each dictating, with alarming specificity, the proper way to arrange and conduct a human life. Vengeance is its chief engine of justice. “The most important fact in North Albania is blood-vengeance, which is indeed the old, old idea of purification by blood. It is spread throughout the land. All else is subservient to it,” Durham writes. “Blood can be wiped out only with blood.”

Historically, self-rule via the Kanun has been the most viable, consistent, and least corrupt option for native Albanians. The code achieved and maintained prominence in part because Albania has been inconsistently and selfishly governed for millennia, and because no indigenous religion has ever quite taken hold in the same way. Modern Albania is around 70 percent Muslim (along with Turkey, it’s one of only two Muslim-majority countries in Europe), but the Kanun still trumps religious law. It is a guiding text in the way that the Bible or the Quran or the Talmud or the sutras are, yet it has no mystical or otherworldly component. It is not a spiritual book; it does not address existential matters. Its rules aren’t interpreted or extrapolated, they’re merely followed. Hoxha’s borrowed maxim—“The religion of the Albanian is Albanianism”—is presaged by the Kanun; the book mandates that oaths be sworn on a “rock,” a triangular stone with three holes that was used to counterbalance a scale for weighing wax candles for church. A besa, or an oath upon a rock, is a grave and sacred vow that transcends any regional or religious differences. Though the rock has religious significance—it was involved in preparations for mass—it’s still of the Earth. It is Albanian.

In his 1953 introduction to The Unwritten Law in Albania, the anthropologist J. H. Hutton makes a case for the Kanun as a primitive but highly functional substitute for a more stable system: “It was no doubt this absence of any such sanctions as those provided by an enacted law and enforced by a settled government, or merely even by the continuity in administration of a single ruling family, which was the primary cause of the firm establishment of the vendetta as the real sanction for all Albanian law and custom.” Hutton evokes Sir Henry Maine, a nineteenth-century British historian who was one of the first scholars to formalize a sociological study of law; Maine believed there is “no such thing as unwritten law in the world.” But Albania’s particular isolation, as well as its extraordinary history of occupations, is exceptional. The only reliable institutions are local, familial. “These communities consisted in the narrower sense of the family, and in the wider sense of the tribe,” Hasluck writes.

In 1991, after the Communist party was overthrown, the Kanun enjoyed an acute renaissance as a guiding text. “The whole region was once again gripped by blood feuds and revenge killings, some over land, and some over ancestral quarrels,” the BBC reporter Robert Carver writes in The Accursed Mountains, a travel narrative published in 1998. “There was no knowing how many were killed every week, but it was certainly many hundreds. Whole valleys now had no men in evidence at all: they were hiding in the tall stone towers of refuge because of clan vendettas.” Carver is unambiguous about the correlation between the fall of Communism, the struggles of a new and faltering democratic government, and the resurgence of blood feuds: “As Democrat control was breaking down, so the old pre-Second World War feudal Albania was re-emerging. A whole society going back to the law of the rifle.”

Later, when Carver finally finds an English translation of the Kanun, he declares it “a profound psychological portrait of contemporary Albania,” a book that betrayed “the very soul of an ancient, proud, and much misunderstood people.” He believed no officials should be allowed to negotiate with Albania, “or even visit Albania,” without having read, studied, and internalized its directives.

Sometimes, the logic of the Kanun is so basic as to seem absurd—“Plundering is avenged by plundering,” it declares in Article DCCLXXXII —yet, on occasion, it contains bits of near-poetic circumspection: “The tongue is soft, but chews everything”; “The house belongs to God and the guest”; “The wolf licks its own flesh but eats that of others”; “Blood is never unavenged.” The Kanun is particularly careful to protect speech: “No one may accuse me of any evil deed for what my mouth caused.” A person can espouse hatred all day long without consequence; all that matters is an invitation to blood via blood. “Words do not cause death; a witch does not fall into blood.”

Because the Kanun is unambiguous, and therefore resistant to modernizing amendments, its dictates can be very cruel. For example, it is vicious to women, explicitly and repeatedly denying them personhood. Per Article XXIX, “A woman is known as a sack, made to endure as long as she lives in her husband’s house.” Her responsibilities include submitting to his domination and fulfilling her conjugal duties. Otherwise, she is so worthless as to not even demand accountability. “Her parents do not interfere in her affairs, but they bear the responsibility for her and must answer for anything dishonorable that she does.” There are two things a woman can do to ensure her own murder: adultery, or the betrayal of hospitality. “For these two acts of infidelity, the husband kills his wife, without requiring protection or a truce and without incurring a blood feud.” A husband retains the right “to beat and bind his wife when she scorns his words and orders.”

Before I flew to the Balkans, I tracked down the scholar and translator who made it possible for Carver to read the Kanun—Leonard Fox, a retired professor now living in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1989, Fox was the first (and remains the only) person to translate the Kanun into English. He is also the author of an academic paper, “An Archetypal View of the Kanun,” that describes Dukagjini’s code as a set of “laws so ancient that they antedate the appearance of centralized government, kingship, autocracy, or oligarchy, with their attendant and inevitable components of coercion and brute force.… These laws strike a responsive chord in us because that from which they arise is part of what C. G. Jung called our ‘collective unconscious,’ the phylogenetic, primordial, instinctual foundations of the human race.”

When we spoke on the telephone, he said the project was born from his own deep curiosity about the text. “I had some Albanian relatives, and I’d read some English-language books about it. What interested me was the way in which it influenced the entire culture of northern Albania and Kosovo,” he said. “It has given northern Albanians their way of life. Even when it was banned by the Communists, it was still there.”

I wondered aloud if the Kanun might disappear if Albania westernized—if the country ever successfully completed accession to EU membership, or if the government figured out a way to establish a viable infrastructure for tourism. “I don’t think it’ll ever happen,” Fox said. “There are still communities in the mountains for whom this text is practically sacred. Once the book came out, I got letters from all over the place—young Albanians in this country and in Europe, thanking me because it was difficult for them to read the original Albanian text, too. It was the first contact they’d had with this thing that was so sacred to their tradition,” he explained. “It’s unfortunate that the government is not closer connected to the ideals of the Kanun, because Albania has really suffered since the end of Enver Hoxha. There have been some really horrible people in the government. It’s a great pity, because they were ready for something better.”

Before we hung up, Fox gently chastised me for using the word “lawless” to refer to contemporary Albania. “I’d be very careful using that term,” he said. “As long as people are following the Kanun, there is no lawlessness.”

In late July, temperatures in northern Albania often crest 100 degrees Fahrenheit by 10 a.m. I’d made arrangements to meet Liljana Luani, a fifty-six-year-old teacher who helps families who have been forced to pull their children from school because of threats related to blood feuds, in the shaded courtyard of the Hotel Colosseo, near the Lead Mosque, one of the few historic houses of worship not destroyed by Hoxha. For eleven years, she has gone into the homes of feuding families, teaching their children lessons and bringing them books, school supplies, food. It is a tremendously difficult and often thankless job. (Earlier this year, the US Embassy in Tirana nominated Luani for the Secretary of State’s International Women of Courage Award, though she did not make the final list of thirteen honorees, as determined by the US Department of State.) While we drank iced Pellegrino and fanned ourselves, she told me a story about a sixteen-year-old boy she had been tutoring, until he was shot between the eyes. “It is a very problematic situation,” she said.

Luani is from the Dukagjin highlands, a mountainous region, including Thethi, just northeast of the city. We talked about the challenges presently facing women and children in Albania. Human trafficking—in which young girls are sold into slavery—has become a considerable problem; in a 2017 US Department of State report, Albania was identified as “a source, transit, and destination country for men, women, and children subjected to sex trafficking and forced labor.” The European Commission estimates that 120,000 women and children are trafficked through the Balkans annually. Luani has advocated aggressively on behalf of equal rights (teaching women how to professionalize domestic trades so they can work outside the home; convincing their husbands to allow it) but her efforts aren’t necessarily supported. The old ways—the cruelly misogynistic dictates of the Kanun—endure. At times, they feel as immutable as the mountains themselves.

The day after I left the Balkans, US Vice President Mike Pence delivered a nineteen-minute speech in Montenegro, addressing a meeting of the Adriatic Charter Summit (presumably, he was attempting to fend off encroaching Russian influence in the region). Pence is the first American vice president to ever visit the country. Leaders present at the summit included the prime minister of Montenegro, the chairman of the council of ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the prime minister of Croatia, the president of Kosovo, the prime minister of Macedonia, the prime minister of Slovenia, the prime minister of Serbia, and Prime Minister Edi Rama, of Albania, who the Times noted “showed up for the summit meeting wearing white sneakers.” “You belong to a new generation of Balkan leaders, and this is a historic moment for progress in the Western Balkans,” Pence said. “I urge you with great respect to make the most of this moment.”

That same week, the Montenegrin Parliament had to institute new formal rules to discourage brawling between its members. “The changes to the parliamentary rules came after a series of outbreaks of violence including punching, slapping, pulling of hair and kicking in the legislature in recent months,” the website Balkan Insight reported. Macedonia, which borders Albania to the east, was facing similar problems. Over a hundred people were injured last April, some severely, after crowds of masked protestors stormed the Macedonian Parliament in Skopje. Members of the nationalist party VMRO—the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization—were upset that Talat Xhaferi, an ethnic Albanian, had been elected speaker of the house.

When Nabolli and I were driving around Shkodër one night, I asked him how he felt about the future of Albania. He and his wife are raising their young daughter here. He said that he and other Balkan journalists get together to discuss this often. His voice was resigned. He will stay. Yet he recognized and opined the perpetual instability of his country, the entrenched corruption, the way that, on bad days, it can seem as if there is no future here, that Albania’s collective unconscious is inconsonant, incompatible with modernizing forces—that the country resists, chokes itself.

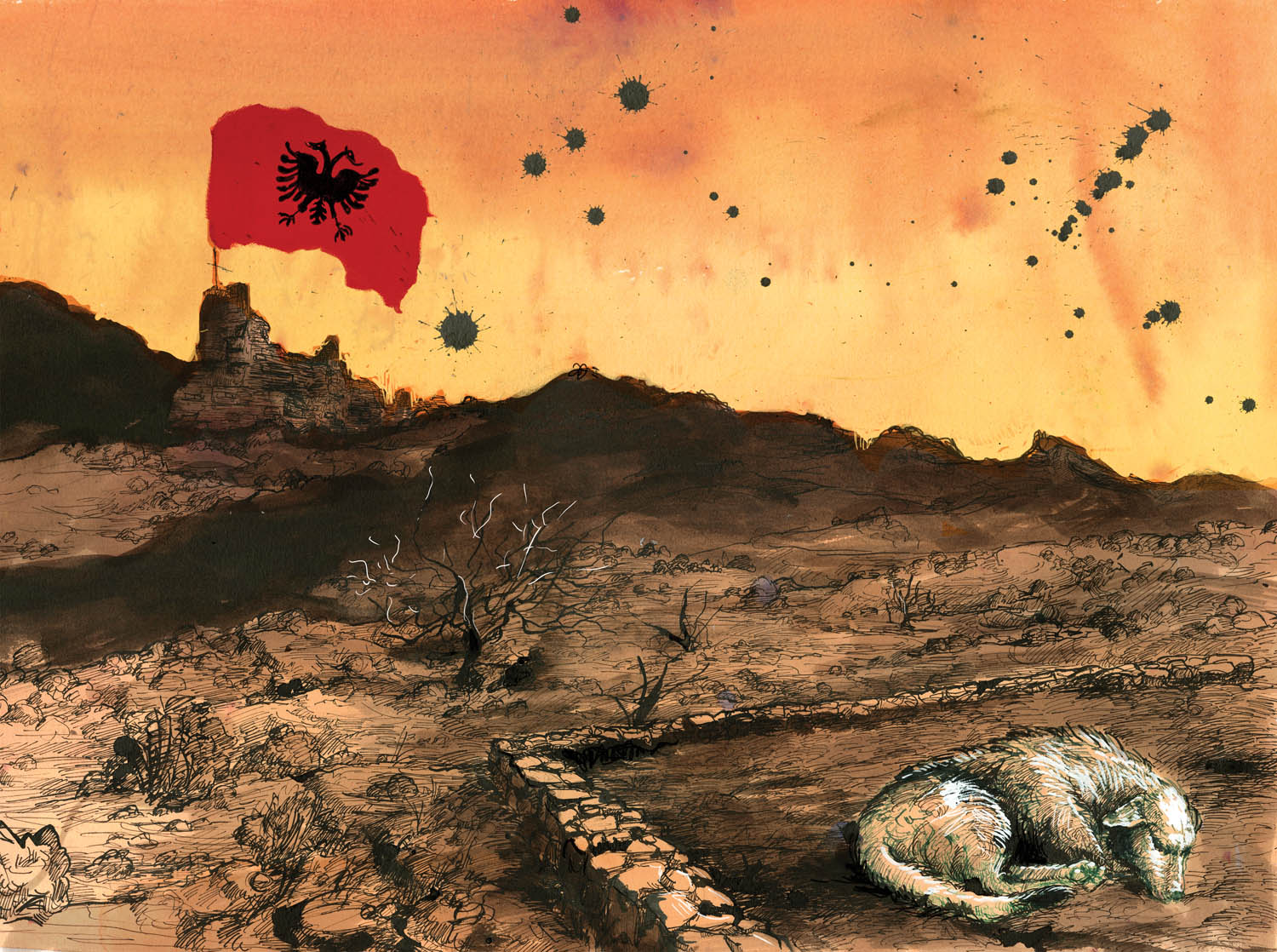

We climbed to Rozafa Castle at sunset. The light was soft and dizzying. Rozafa was the site of at least two significant sieges: the Ottomans, in 1478 (Ahmed the Dervish, an Ottoman historian, called it the empire’s only “hope of passage to the lands of Italy”), and the Montenegrins, in 1912 (they believed Shkodër was their lost and rightful capital). When I asked Nabolli if he knew anyone, personally, who was involved in a blood feud, he seemed surprised by my question. Hadn’t I seen for myself the prevalence of the custom, how inescapable it was? “Yes, many people,” he said. Their stories are similar, now recounted in local and international newspapers, or in low-budget documentaries: men living their lives alone and in fear, waiting to suffer for the sins of their relations. The horizon was a hazy, wavering pink behind a big, flapping Albanian flag. It was as if its crimson had stained the sky.

9 Comments

A beautiful - if deeply melancholy - piece of writing. Thank you.

Interesting, evocative, but also perhaps too pessimistic? I have not been to northern Albania, but on a 2-week bike trip around southern Albania I found the people friendly, helpful, honest, and above all at pains to let visitors know that Albanians are not "all" criminals, gangsters etc. etc., and to ask that visitors tell the rest of the world. The landscape was beautiful, the food good, the roads good, the prices cheap - so I would hope that this piece does not deter people from visiting a fascinating and historic country.

When I served in the Balkins in the early 90's with UNPROFOR I thought that part of the Balkans was the most batshiite crazy place in the world. From the article it is plain that I was wrong. Albania seems much worse than Medak or Krajina.

I’m married to a wonderful woman who is half Albanian and she has a very bad temper who knows how to put me in my place.

Chris

The piece might have mentioned the Albanian writer Ismail Kadare's "Broken April," the first half of the novel at least brilliantly evoking the ancient blood feud.

Ughhh... truly awful, and just think about it. This is whatVlad Putin wants for our nation. Truly, the Balko-slavic way of life is an anathema to joy, civilization and freedom of expression. It comes as no suprise that the age of reason never happened with these people.

Fascinating article. Thank you.

Very interesting and well-written; Ms. Petrusich is as lucid a writer as brave a reporter. A bit surprising though that the novel Broken April by the famous Albanian author Ismail Kadare was not mentioned - it incorporates the very same insights. Nothing seems to have changed since 1978 when it was published or since the 20's or 30's when it was set.

1. Albanian languange is not spoken "ocassionaly" in Kosovo, Macedonia and Montenegro.95% of the Kosovo population is Albanian ( their mother tounge is Albanian) as is the case with 30% of the population in Macedonia and a small minority in Montenegro.

2. KLA was a counter to Milosevic ethnic cleansing agenda. It was not a terrorist organization as you may allege, and it had no link to Al Qaeda whatsoever.