Just as the World Food Program charter plane en route to Nairobi sped along the dirt airstrip to its lifting speed and began its ascent, I looked down at the sprawl of white tents and clusters of globular huts below where I had just spent a life-altering three days and vowed never to write about the experience of visiting the Dadaab Refugee Camp. Instead, I would content myself with making occasional trips to volunteer, and until then and meanwhile, help raise awareness about the oldest and largest UN administered refugee camp in the world. (Is it coincidental that this camp is also in Africa, the most historically neglected continent on earth?)

On the surface, the brutal fact of refugee life—listless days in the desert praying for resettlement, interminable lines awaiting food rations, dark nights fearing assault, the ongoing, existential sense of dereliction and desertion—did not seem the stuff of poetry. The desperate lives of the largely Somali population, who fled the long-standing civil war and famine in their home country to the Northeast Province of Kenya, seemed suited more for a foreign relations policy paper delivered at a geo-political conference, rather than beautifully captured and made digestible in the quaint stanzas of a poem and somberly recited at a summer writers’ conference.

And although I had been sent there to proselytize about the integral and synthesizing powers of poetry to impart a provisional understanding of our lives, especially those disrupted by travesty, I privately decided it was not my responsibility. I had invoked poems by Pablo Neruda, Lucille Clifton, and Joe Brainard, but upon reflection, I did so with faint enthusiasm, so struck was I by the nearly surreal experience of beholding at once so many in the Horn of Africa living precarious, indigent existences. At the time of my visit, tens of thousands in Somalia had starved to death and over a thousand people per day were seeking asylum and escape from the drought that had set upon East Africa. Even as I spoke about the potency of artful language, I was asking myself, “What am I doing here?” and “What collapse of reason can account for such massive numbers of victims of war and natural disaster?”

As I watched underfed children whose dust-covered faces, hands, and feet turned their bodies into sand ghosts, my children were back home in Vermont, enjoying the privileges of life in green, northern New England, their futures secured and intact. While I walked in the outdoor market at Ifo, where vendor stalls sold everything from M-PESA mobile phones to mattresses to suspect vegetables, the Farmer’s Market in Burlington, my home city of nearly ten years, was abundant with pesticide-free vegetables, organic milk, artisanal cheeses, grass-fed fresh meats, and gluten-free vegan fair. Feeling my advantages and dispensations so acutely, I truly believed my comfort did not authorize me to speak. And further, hadn’t I in the past expressed a belief those who claimed to write a poetry of witness were most often exploitative and self-serving?

My crisis, then, was due in large part to a dubious relationship I had to the art of poetry and its function and role in society. The large chasm between my life and that of the refugees opened up wide enough for me to realize on that plane that I temporarily sided, after all, with W. H. Auden, when he struck his famous line, “We must love one another or die,” and concluded a new poem by explaining, “Thousands have lived without love, not one without water.” It was undeniable: poetry could never fix the lives of those escaping drought nor those displaced by war. Our hosts from the United Nations, under serious threat of harm, along with a core committed group of aid workers from CARE, FilmAid, and the Windle Trust, were performing eminently practical work that was making a real difference for desperate people. What was a poem compared to that?

But then, one morning, a month later (and, ironically, at a summer writers’ conference), I wrote a dramatic monologue in the voice of a Somali boy I had heard about during a security briefing by Michael Chilla, chief security officer at Dadaab. The boy, about twelve, had been recruited in the market in Dagahaley by al Shabaab. Lured by the promise of enough money to care for his family, he joined. But after a month, disillusioned, he escaped and returned to Dadaab. My doubts about the limits of art could not police my imagination. I began to envision his life, all of their lives—the aid workers, the Muslim women in the classroom, the young aspiring filmmakers, the team of refugee journalists. I was astonished by how such “flying leaps” (as Robert Bly called them) engendered empathy and allowed compassion to bridge the distance I felt from the suffering people of East Africa.

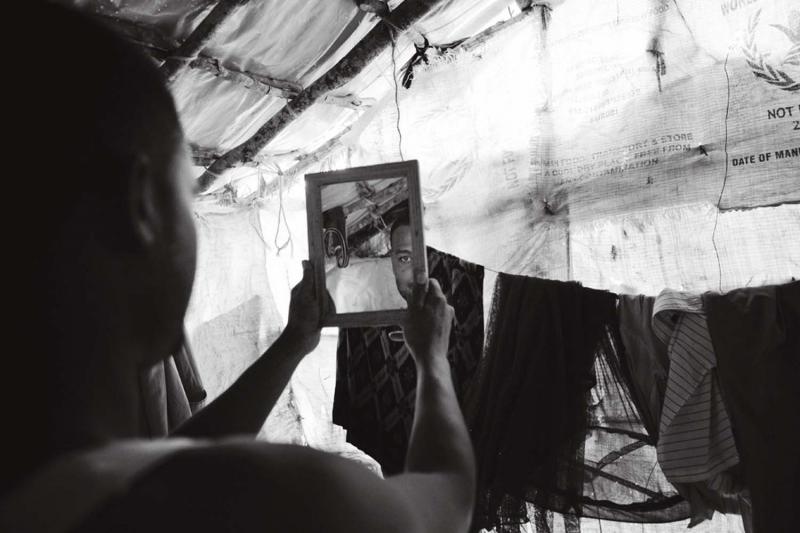

What gripped my psyche most was their vulnerability. A tent in a refugee camp is supposed to be a temporary way station on the road to resettlement. A generation of elders has now died in Dadaab, and a generation has been born and raised, having never known anything but outdoor latrines, trash caught in the barbs of thorn trees, and twice-a-month food rations. The images of Dadaab manifest involuntarily, and I do my best to pay attention and write them into existence. I strive to capture the sense of resilience I observed there—and a lightheartedness that defies desperation. A well-made poem is an interim result that must reflect the possibilities of a new tomorrow, one changed by the poem’s presence in the world.

Through the act of writing over these past months since my return, I have relearned the value of the art I cherish. What lines I have written, and will write, I hope reflect poetry’s power to change a culture—and legislate our world—as much as any policy paper.