Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life, as clear as crystal, flowing from the throne of God.

—Revelation 22:1

On January 10, 1991, Ambilikile Mwasapila dreamed a cure for AIDS. A woman appeared to him, a woman he knew to be infected with HIV, and God sent him into the bush for a cure. It was only a dream, and at the time, Mwasapila, a Lutheran Pastor in the remote Northern Tanzanian ward of Loliondo, was not sure what it meant. He continued to work in Wasso, an outpost town surrounded by dry and dusty plains occupied by the cattle herding Maasai, and earned a reputation as honest and upright, humble and kind. In 2001, he retired from the ministry and considered moving back to the more populous Babati, where he had lived as a young man. But he heard the same voice, God’s voice, in dreams, telling him to stay, for there was work for him in Loliondo.

Mwasapila remained, and the voice returned many times in the next few years, sometimes when he slept and sometimes when he just closed his eyes. He saw a recurring vision of a multitude gathered under a ridge. He saw tents, cars, and even security guards. In 2006, he moved to a small house in the village of Samunge, at the base of the ridge he had envisioned. One night, he dreamed of a ladder stretching across the sky from the west to the east, colored red as blood. The ladder stopped directly above him. Then, in 2009, God’s voice returned with specific instructions. God told him to climb into the hills to find the bark and root of the tree the local Sonjo people call “mugariga.” There was a woman in the village whispered to be HIV positive, and on May 25, he gave her a cup of liquid made from boiling the bark. Three weeks later, God’s voice told him the woman was now cured. Later, doctors from the Wasso Hospital tested the woman—and she was shown to be HIV negative.

Mwasapila continued to give the cup of liquid to people with HIV/AIDS, telling them that, after seven days, God would seal the mouths of the viruses inside them. Unable to feed, the virus would die within weeks. In 2010, God told him to give the same medicine to patients with cancer, and later with diabetes, asthma, and epilepsy. In October, the word had spread so that Mwasapila had visitors nearly every day, some travelling a day or more to see him.

In November, a newspaper journalist named Charles Ngereza happened to be travelling from Lake Victoria to Arusha. In the small town of Mto Wa Mbu, two hundred kilometers south of Samunge on a major route, he saw crowds of people waiting for a bus to take them north, to the middle of the bush. He joined the crowd to see where they were going, met Mwasapila, and interviewed several people who claimed to have been healed by drinking the cup of liquid. The story ran in the national papers.

In January 2011, a contingent of church officials from the Evangelical Lutheran Church, Mwasapila’s former employer, visited Samunge to satisfy themselves that he was not a witch doctor. They returned convinced, travelling to different congregations to bring the news of a new gift from God. More people came to drink a cup of the cure, and there was now a constant queue of vehicles in the road leading into the village.

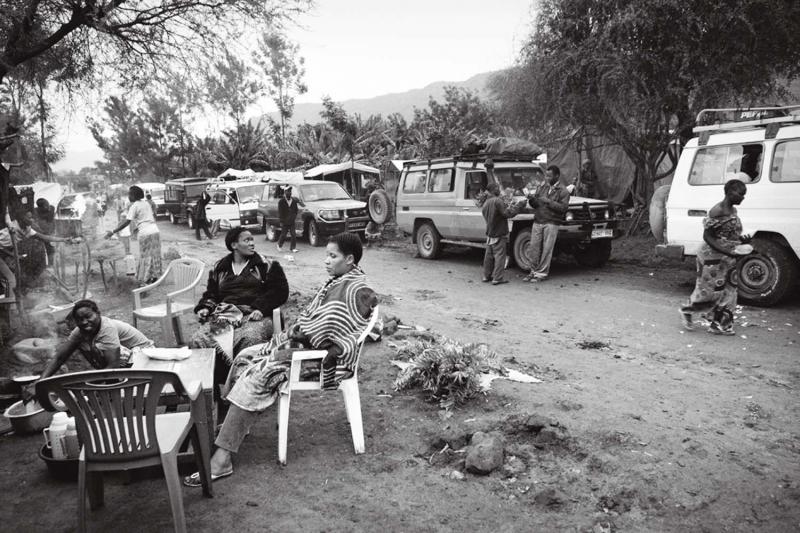

By March, Mwasapila’s earlier vision had come true. The line of cars and buses to continued to Samunge reached over twenty kilometers on a road that was usually rarely travelled. People waited for days to see Mwasapila and drink a cup of the liquid. Tanzanians took to calling him “Babu”—meaning “Grandfather”—an appellation of respect and affection for any old man. People with chronic illnesses spent small fortunes hiring transportation and travelled for days, using whatever conveyance they could afford. Anybody who owned a car or bus could earn money packing it full of pilgrims seeking Babu’s cure. Entrepreneurs brought trucks with supplies and sold them off the backs of motorcycles for three times their normal value. Travelers slept on the ground, washed in the river, and defecated in the bush. Dozens died waiting to see Mwasapila.

To many Tanzanians, Babu’s medicine was a miracle, a one-step cure. To expatriate tour operators or visitors, it presented a puzzle: how could the locals believe drinking a cup of liquid once would cure a slew of diseases? To many doctors and health professionals—expats and Tanzanians—it was a terrible setback. HIV/ AIDS, diabetes, and high blood pressure, could all be controlled effectively with modern medicine. Years of effort had gone into developing effective medications and soliciting aid for East Africa, and years more went into convincing Tanzanian patients to submit to HIV testing and maintain the proper regimen of anti-retroviral drugs (ARVs). Now many hundreds of people were abandoning ARV therapy, believing themselves cured. Some doctors, respectful of their patients beliefs, quietly advised them to continue taking medications, no matter what they were told at Samunge. A few openly predicted disaster.

“It’s just a little farther, we are almost to Digo Digo,” Simon softly calls from the back of the Land Rover. It’s 4 a.m. on June 29, very dark, and I’m driving over a dirt track with photographer Sarah Elliott and Simon, a Maasai guide and translator. We woke up a little after midnight to travel from Ngare Sero village, hoping to make Samunge by dawn. The plan came together at the last minute, and without inquiring about the proper paperwork we gambled that if we just showed up at Samunge, I could talk my way into an interview with Mwasapila.1 We are taking a route the map calls merely “Bad Road,” ascending the Gregory Rift Escarpment in a series of tight turns through hills and canyons. It’s the same road the government plans to turn into a highway that will cross the Serengeti National Park, joining the large city Arusha, with communities on Lake Victoria.

We’ve already been stopped twice in the small hours, and both times, Simon has had to crawl from the back of the overstuffed car and argue with armed police, who used our lack of papers as an excuse to shake him down for a “fine.”2 After the second shakedown, the newly appeased guards made the friendly suggestion that we take an alternate route to Samunge, through a nearby village called Digo Digo. That route stays clear for emergencies and allows supplies and VIPs to enter Samunge without waiting in the queue. Unfortunately, the way is not so well worn, and we take a wrong turn—rumbling by small settlements and farms, and sliding in sand and fording rivers before Simon finally admits we’re lost.

He crawls out of his car to knock on the door of a mud house. By the light of a kerosene lantern, a woman gives him new directions and, now confident, we drive for another hour, joining better roads, and enter Samunge, just as the sun rises. Samunge is stark and beautiful; the soil is a red clay and, perhaps because it’s in a river valley, the vegetation seems more green and vital than the drier highlands nearby. The narrow Sanjan River flows southeast through the Soda Flats below, entering the alkaloid Lake Natron. Along the way, it crosses the rift where two great tectonic plates slammed together and have been pulling away from each other for last forty million years, forming the Great Rift highlands, volcanoes, the African Great Lakes, and slowly revealing humanity’s origins in nearby Olduvai Gorge. Mwasapila’s new Eden is less than a hundred kilometers from our most famous early ancestors.

Samunge lies at the base of a three-peaked range of hills that looks like the Southern California chaparral. Most of the houses are small, framed with sticks, and fleshed with mud. Dirt roads are lined with drab tents and makeshift tarps. The village slowly fills with people seeking medical help, brought by rickety vehicles. The whole scene strangely resembles the set for M*A*S*H. A disembodied, Swahili-speaking Radar O’Reilly shouts instructions through a tinny bullhorn somewhere. People are to gather in a half hour to hear Babu speak.

Simon goes off to inform officials of our arrival. A crowd is forming at a widening in the main road. People are walking from their cars parked several hundred meters away. Some look obviously unwell, limping or shuffling, helped by relatives. One woman’s foot is twisted 180 degrees from her ankle. Simon returns with a bleary man in striped pajamas; he claims to be an immigration official and asks our business. I explain we are journalists who have come a long way to learn about Babu. “Do you have a permit?” he asks. This is the first I’ve heard of any such thing; I tell him no.

He nods, and politely directs us to sit and wait at a small open-air café. A young soldier in green fatigues with a dinged up assault rifle stands a few meters away. We begin to hear Swahili over the tinny speaker again, and Simon says it’s one of Babu’s assistants explaining how the medicine will be dispensed. Simon has brought other Westerners here before—Americans or Europeans on Safari who wished to see the faith healer. He says they usually pay a small fee and then they get to see Mwasapila.

But ten minutes later, the formerly bleary man returns wearing an immigration uniform. Now significantly more imposing, he explains that I will have to “fulfill a process” to get permission to speak to Mwasapila. I ask if I can fulfill the process on the spot. He sighs regretfully and says it’s not within his power to help me. Simon pleads on my behalf, hinting we might pay an informal fee, but, to Simon’s surprise, this has no effect. Apparently, journalists are not as welcome as tourists.

The immigration officer disappears, and Simon tells me the voice we now hear over the speaker is Mwasapila. The voice is crisp, medium-pitched, and slightly nasal, and we hear him list the diseases the medicine will cure: diabetes (“sugar,” as Tanzanians say), hypertension (“blood”), cancer, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS. The officer returns saying I need to travel to Wasso to speak to the district administrator who will help me obtain the proper papers. “When you walk to your car, you may just peek at Babu over there.” A man in a tie, standing nearby objects in Swahili, and Simon tells me not to peek at Babu after all. I obediently look away, hopeful that I will get a chance at a better look later.

Wasso is a ninety-minute drive away, and the district administrator is much less patient than the immigration officer, and equally un-budgeable. I have to return to Arusha, the largest city in the north, immediately, and I may conduct no interviews. We leave at first light the next day, and after driving an hour, we spot a minivan from Kenya on the side of the road, its passengers milling around. I pull over and speak to a man who tells me he has just taken a cup of the medicine to cure his diabetes. His eyes are bright, and he says with excitement, “Already, my headache is completely gone.” He says he will stop taking insulin in a week if he continues to feel better.

Another slight man with pale skin approaches the Land Rover. He says, “Excuse me,” in formal English, his voice high and weak. “I have stomach cancer and diabetes.” His belly is distended to the size of a watermelon, and his feet are extraordinarily swollen. “This bus is very cramped, and I very uncomfortable. May I ride in your car to Arusha?” He says his doctor told him he has a month to live, but he is now hopeful the cancer will vanish. I explain our car is full, apologize, and wish him good luck.

After several hours, we descend from the highlands to Ngare Sero on the plain, where Simon makes his home. He introduces me to a man who says his stomach ulcers and indigestion have vastly improved since he visited Samunge last February. This man heard about Mwasapila when Lutheran Bishop Thomas Laizer came to his remote village in the Ngorogoro highlands with word of a miracle cure. As we talk, the young village chairman grabs Simon’s elbow. The Loliondo administrator has sent word by radio that an American journalist might come through the village, and he must not be allowed to conduct interviews. The chairman turns to me and says in English, “If you had come here first, there would be no problem, but now, we have heard the word from Loliondo.” We say a hasty goodbye to Simon and make the five-hour drive back to Arusha.

In 2006, Francis Tesha tested positive for HIV. He lived in Wasso, the outpost town where Ambilikile Mwasapila had been a Lutheran Pastor before his retirement. Francis was about forty, married, and had a job at a local hunting lodge partly owned by the royal family of Abu Dhabi. His employers liked him so much that they brought him with them to Abu Dhabi to work for months at a time. When they heard about his diagnosis, he was fired and sent back to Wasso. His wife died a few months later—of malaria. Their neighbors believed the shock weakened her, and that she may have also had HIV, but she refused to be tested or take medication.

Francis did accept ARV therapy and took the pills every day. He joined the HIV support group in Wasso and became its secretary. He was gregarious and well liked. In October 2010, he heard reports of a healer in Samunge who could cure HIV. Although Francis felt healthy, he figured if he killed the viruses in his body, he could be certified HIV negative, allowing him to get his old job back. On October 2, he took a bus from Wasso to Samunge, drank the liquid, and spoke with Mwasapila, who assured him that after twenty-one days, the virus would be gone from his body. Francis returned to Wasso in high spirits, telling his friends at the HIV support group that Babu could free them of the virus and the ARVs.

Francis stayed off the ARVs for three weeks as instructed, and then excitedly went to the hospital for an HIV test. To his dismay, he was still HIV positive, and in fact, his CD4 count had diminished.3 He reluctantly began taking ARVs again, but now he felt much more vulnerable to side effects, becoming dizzy and nauseated when he took the drugs. To settle his stomach, he occasionally skipped his ARVs. In February, he was hospitalized for a secondary infection and, when he got out a few days later, started saying he no longer believed in Mwasapila’s medicine. His neighbors whispered that Francis had a new girlfriend with whom he had sex with no condom. Babu had cured him, they reasoned, but he allowed himself to become re-infected.

Despite Francis Tesha’s faint warnings, by February of last year, Babu was a national phenomenon, and the BBC reported six thousand people in line at his clinic. Unlike Francis, many people returned from Loliondo with powerful testimonials. Diabetics swore their blood sugar had normalized and they could drink sodas and eat bread again. Stomach ulcers subsided, and aches and pains vanished. Newspapers reported the woman Babu treated in 2009 was confirmed HIV negative, and people excitedly related stories of cousins or neighbors who were cured of HIV/AIDS. The Tanzanian government seemed internally conflicted about how to respond to Mwasapila. In March, the Ministry of Health announced they were ordering the healer to cease his activities. At the same time, ministers from other parts of the government enthusiastically made the trip to Samunge. Dr. Salash Toure, the Arusha Regional Health Officer, declared publically that his hospital had tested dozens of people who claim to be cured of HIV, and all had tested positive. However, the influential Lutheran Bishop Thomas Laizer lobbied on Mwasapila’s behalf, calling the liquid “a gift from God.” The lines at Samunge grew.

On March 25, the government reversed course, announcing that the herbal concoction was safe to drink, and that they would take no action to stop people from visiting Samunge to take the cure, but would start registering vehicles and providing basic services like first aid and toilets to the overtaxed village. The Ministry of Health appointed a team of doctors to study the effects of the liquid. In April, the government acknowledged eighty-seven people had died while in transit to Samunge.

Katy Regan, the American managing director of Support for International Change (SIC), felt compelled to go directly to the Ministry of Health to clarify government policy toward Mwasapila. The NGO provides treatment and counseling to people with HIV, and she estimates 20 percent of their clients abandoned ARV therapy in March or April. Some of her Tanzanian colleagues told her Mwasapila’s cure worked, and she had to fend off HIV patients who wanted to borrow the organization’s truck to make the trip. For Regan, this was a huge set-back. “You never want to see someone going off treatment, especially when you’ve worked for years to have it be part of their routine,” she said. But Regan still refrained from offering an opinion of Mwasapila’s liquid out of respect for her clients’ beliefs. “I didn’t want to offend someone who decided to go, and I sympathize with someone who wants a cure.”

Not all health workers were as circumspect. Pat Patten was especially blunt: “I don’t believe in faith healing, I think this is a deception. And I’m a Catholic priest.” Patten is also a pilot and the director of Flying Medical Service. He has lived and worked in Tanzania for over thirty years. A Spiritan priest, he wears secular jeans and t-shirts while flying bush planes to remote settlments, providing regular rotating clinics, and flying emergency evacuations. “I’m open to a powerful placebo effect, but placebo effects only relieve the symptoms, never the root of the problem.”

He remembers the shock of flying over Mwasapila’s village February, looking out the window of his Cessna 206 to see a traffic jam. Now, after talking to doctors throughout the region, he is convinced Mwasapila’s treatment has led to disaster. “What we’re seeing is a lot of AIDS patients dying in hospitals because they’ve stopped taking medicine. Diabetics are now going blind, suffering kidney failure, experiencing swelling in their hands and feet, and getting diabetic sores on their extremities.” He worries about an outbreak of drug-resistant tuberculosis and adds, “These are all unnecessary deaths, all of them.”

And the famous story of Mwasapila’s first patient, Patten claims, was a lie. He spoke to doctors familiar with the case who said the woman had never tested positive before taking Babu’s cure, that she only feared she might be infected—but, Patten says, “the damage has been done.”

And the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. No longer will there be any curse.

—Revelation 22:2–3

Back in Arusha, after my first failed trip to meet Mwasapila, I spend the day in government offices, talking to clueless clerks, waiting in hallways, and pleading with bored and impatient officials. Nobody seems to know or care who can issue the proper documents to allow an interview. In the late afternoon, I find myself in an office with Jotham Ndereka, the Arusha Regional Information Minister. I explain for about the ninth time that I need a permit to go to Loliondo to interview Mwasapila and take photographs and he says brightly, “Yes, this is possible.”

“It is?” I say, surprised. Ndereka explains that I need a filming permit, such as one might get to make a TV commercial, and for an extra fee, the Ministry of Information can issue one in a week. I spend the next week looking for patients with HIV who drank Mwasapila’s liquid but can find nobody willing to talk to me. I do manage to talk on the phone with the Wasso Hospital Administrator, Madam Josephine Kashe, who invites me to visit in person if I make the trip to Samunge.

A week later, I rent the same Land Rover, load it with supplies, and return to Jotham’s office. The minister presents himself in a gray suit, smiling smugly. He hands me a handwritten “Filming Permit” signed by the National Minister of Information. I thank him and start to leave when he says, “Wait! If you look at the permit, you will see that your activities are to be done under the supervision of the Arusha Regional Information Officer. This means I am to accompany you.” My heart sinks. It appears the government has assigned me a ride-along censor.

“I do not think that will be possible; I have to leave today,” I say.

“Today?”

“Yes, you told me the permit would be ready, so I have made arrangements that I cannot change.” He leaves to make a phone call and returns five minutes later to say that everything is fine, his boss has given him permission to go with me for three days. I tell him I am planning a four-day trip, and he says that’s fine, too; he’ll just need me to pay a forty-dollar per diem for his meals and lodging.4 He has me over a barrel—I need him to ensure an interview with Babu—so I ask, “How soon can you be ready?”

Two hours later, we are driving into the setting sun, five hours behind schedule, but moving at last. Jotham has changed into a Tommy Hilfiger shirt, loose jeans, black leather jacket, and baseball cap. He looks like an American executive at his son’s soccer game in Connecticut. For the next four days, we will be constant companions—and frenemies. We call each other Mr. Jesse and Mr. Jotham. He will claim to help me, but apart from arranging an otherwise impossible interview he will offer mostly foot-dragging and his own unverified opinions. For my part, I will act grateful and keep my skepticism to myself. We talk about world leaders—he admires Mandela and Qaddafi—and acknowledges the latter should have stepped down while he was still popular. He admires John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, and Dale Carnegie. The night we drive west from Arusha, Jotham recalls the time, when he was just a boy, he saw Henry Kissinger on an official visit to Tanzania. I say, “Oh, yes, he was Nixon’s Secretary of State.”

“Yes,” Jotham says. “Also, he was with President Ford.”

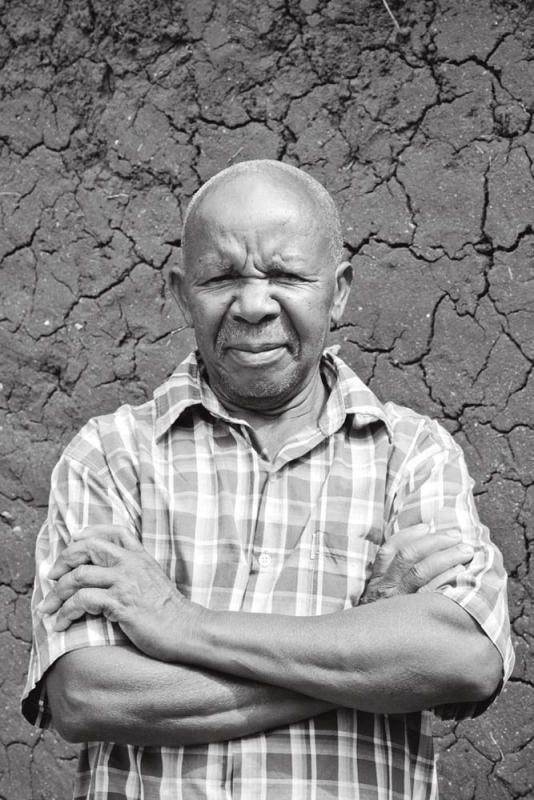

I once again pull into Samunge at dawn, just as Mwasapila is preparing to greet his visitors. At the widening in the road, Mwasapila’s medicine station, a tall, middle-aged, balding man addresses the gathering crowd. He wears a clean shirt and tie and speaks with a high throaty voice in Swahili, using the tinny public address system. After a time, he pauses and tells the crowd they will now hear from the man they came to see. Reverend Ambilikile Mwasapila takes the microphone. He is a short, old man, with close cropped, white hair and a round face. He greets the crowd by lifting one hand high above his head, silently waving hello. Several hundred hands rise to return the greeting.

He begins speaking in Swahili, first acknowledging he is the same Babu they’ve seen on TV or in the newspapers. Then he launches into a practical FAQ about the medicine itself, taking on the tone of a shift supervisor laying out the safety rules of the new machinery: Okay, folks, there are only two size cups of medicine, child and adult. It doesn’t matter how large you are: you still only get one cup. (This draws laughter.) If you vomit here in Samunge, they will give you another cup. If you vomit after you leave, don’t worry, the medicine has already worked.

He lists the diseases the liquid cures, but he stresses: You’re not immune, just cured. Don’t engage in risky activities like unprotected sex. By all means, don’t commit rape or be promiscuous. Keep your diet moderate. Don’t drink any alcohol today because it may interfere with the medicine.

After covering the practical matters, the speech becomes more theological, and Mwasapila takes on the familiar rhythm of a Baptist preacher, asking for assent every few moments. I don’t know anything about medicine. I was surprised when God called me to give you medicine. It is neither the tree nor the hand of Babu that heals. It is God who cures. He has put his power in the medicine, but he could have cured you directly. Okay?

Yes!

There is no illness that is too tough for God. He has decided to eradicate this disease from all over the world. We associate it with Him, saying: “God has brought it; it is a punishment by God,” but that is not true. It is the devil who has brought this disease. Do you hear?

Yes!

People tell me they have to take ARVs every day for HIV or pills to control diabetes, so after drinking from the cup, should we continue with our drugs? I want to be clear about God’s instructions. He told me the medicine here is stronger than the drugs; it takes over from the drugs, unless you just want to be a slave of the drugs. You can keep taking those drugs like a person swallowing clay.

The entire speech lasts for about twenty minutes, after which he concludes with a short prayer. People begin shuffling to their cars, and an East Indian man from Kenya taps Mwasapila on the shoulder. He asks in English if he should continue taking his blood pressure medication but the healer doesn’t understand. The two struggle to communicate for a moment, and then Mwasapila is called away. One of his assistants, who looks about sixteen, overhears and tells the man in English, “You should throw it away.”

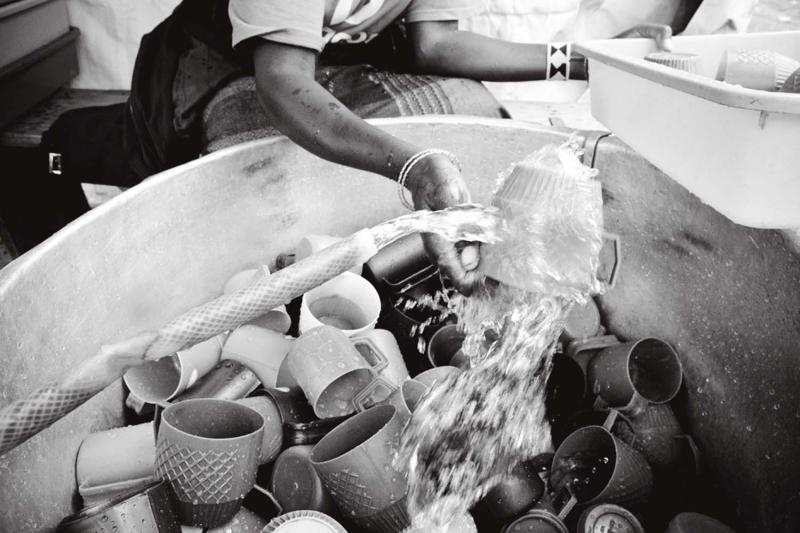

Samunge transforms itself into the world’s largest brew-through, serving over a hundred vehicles in roughly an hour. There are Safari vehicles, Toyota HiAce minivans, Toyota Coaster minibuses, and full size coach buses as well as a handful of private SUVs. They pull up to Babu’s station and workers of all ages carry trays of bright plastic cups, placing them into hands stretched-out from windows. One little girl drinks her cup and vomits out of the window a few seconds later. Workers quickly wash each used cup and return it to service. Mwasapila, with his head bowed, works quietly alongside his assistants, ladling the liquid into trays loaded with cups. After each vehicle is served, it turns left and uphill, looping behind Mwasapila’s station, and begins the long trip back to Arusha, Kenya, or even farther-flung destinations.

An hour later, I find Mwasapila resting in a white plastic chair on a patch of red earth just a few meters from his newly built, but modest block house. He has on a printed t-shirt, green pants, and pink low-top Converse All-Stars knockoffs. He shakes my hand and gestures for me to sit down.

A handful of people gather around to listen. Through Jotham, Mwasapila tells me his given name, Ambilikile, means “one who was called,” and explains about first seeing the visions of this place, Samunge, in 1991. I press for details about his visions, and whether he actually sees God. He says he never sees God, only hears a voice. When he tells about the first woman he treated for HIV in 2009, Jotham tells me, “I would ask about the patient who has been cured of HIV, but he said that she is living far away. Maybe ask the next question.”

I ask Mwasapila why he won’t take his cure to Arusha, Dar Es Salaam, or any other populous place so people don’t have to endure hardship, spend their savings, or risk death in order to travel here. Mwasapila’s answer is that it’s God’s choice. If I was another healer, I might advertise and travel here and there, but God chose here, so I will do my work here. If he decides later that I should move and go to another place, then I will go.

He tells me the medicine works by faith. To be cured, one must drink and believe. I ask if a Muslim, Jew, or Hindu would be healed as well as a Christian. God doesn’t look at the religion; he looks at the person who comes here with belief of faith. If they used the medicine, they will get better.

As we talk, the tall bald man who earlier spoke to the crowd pulls up a chair and begins to listen intently. He says nothing at first, but begins to chime in during Jotham’s translations, emphasizing or elaborating certain points. Un- like Jotham, or Mwasapila, he seems impatient with my questions and scowls at me. The effect is disturbing, and I start to get the sense that I am no longer interviewing Mwasapila but instead arguing with this unidentified man. Finally, he asks me whether people know about Mwasapila in America, and I say there’s only been one newspaper article. “I think in America we are used to putting our faith in doctors even though we are also very religious. So some people will say, ‘That sounds like it can’t be true.’ Other people will think, ‘That sounds like something I would like to see for myself.’”

The man tells me Americans should read Revelation Verse 22 Line 1 through 3. “You will see what God did during Jonah’s time.”

“Since you have now offered something, may I have your name?” I ask. This is apparently daring and makes the small crowd titter.

He tells me it’s Frederick Nisajile and that he works for the Tanganika Christian Refugee Services, which I later learn is an NGO affiliated with the Lutheran Church. Both Frederick and Mwasapila seem intently interested in America. The healer predicts many more people will come. God has already shown me people from Asia, European, Americans. Right here is not big enough. The place to do this service is behind this mountain on the great plain.

Frederick and Mwasapila both want to know what American doctors or drug companies would think if they heard about this cure. I joke that they probably wouldn’t understand, and would instead take the plant to test in laboratories to extract and make money.5 Frederick and Jotham both chuckle. Sensing my audience will end soon, I make one more attempt to ask an important question. I explain I’ve spoken to at least one person who believes there might be something wrong with Mwasapila’s brain, causing him to hear God’s voice. “And I just have to ask, respectfully, did you ever wonder, when you first heard from God, if your brain was playing a trick?”

Jotham hesitates, and then starts to translate this, but Frederick emphatically cuts him off, almost shouting, “No, no, no!”

He launches into an explanation in English that I barely understand, saying David and somebody else in the Bible heard God’s voice many times, and in David’s case, he spoke to an elder to verify it really was God. He claims Mwasapila heard God’s voice for nearly twenty years before acting on the instructions, even writing down the date each time he heard the voice. His point seems to be Mwasapila has done his due diligence. Frederick says, “Now, forget about that. After hearing all of this, what is your comment, sir? Do you believe people can be cured through voices or this medicine?”

Surrounded by the faithful, my skepticism feels like a dirty secret. Struggling to form a polite answer, I tell Frederick that while I have heard of many people who seem to be doing much better with minor complaints or even diabetes, I am still trying to find people who have had HIV who could tell me directly what happened to them. “I do not know what to believe,” I say. “I think if I were suffering I would take the medicine though.”

Frederick tells me to drink a cup of the medicine right now, and I say that I will, even though I am not suffering. Frederick says that we all have many unknown problems with our body and I may be cured without knowing it. Then he tells me to swallow the entire dose; don’t try to keep a small amount in my mouth to take back to a laboratory.

The audience is over, and I thank Mwasapila, who just nods and shakes my hand. Frederick walks me down to the hill to the road, where plastic cups of Mwasapila’s cure sit on a card table. A small crowd follows to watch the action. He presses a cup into my hand. The liquid is warm and slightly bitter, with a subtle and distinctive flavor, like anise or ginseng.

Later, I speak with Madam Kashe over the phone, and, despite the bad connection, it sounds like she has found a patient for me to talk with. Jotham spends about two hours eating lunch and chatting with Frederick and a couple of policemen, while I wait impatiently in the car.

Much later, when I read the translation of my audience with Mwasapila, I will realize Jotham blatantly mistranslated a small part of the conversation. When Jotham asked about his first patient, the woman he treated for HIV in 2009, Mwasapila actually responded that she lived in Samunge, and might be available to talk. This is most likely the same woman Pat Patten told me about, the woman who famously tested HIV negative but according to Patten, had never been HIV positive. Jotham knows full well I am trying to find people who have taken Mwasapila’s cure for HIV, but he says nothing as we drive towards Wasso, away from Babu’s most famous patient.

In Wasso, Jotham introduces me to the District Medical Officer, and I interview him outside of a loud bar while PA speakers blare global hip-hop in the background. His answers are noncommittal. When I ask him if there’s evidence that Mwasapila’s cure works, he says that many diabetics have demonstrably better blood sugar levels after drinking the liquid. He says he knows of no cases of HIV patients testing negative after taking the cure, but he also says some have shown small improvements in their CD4 count. “The ministry of health is conducting a study about this now, and you should really go to them for answers.” I ask him if he can help me speak to HIV patients who went to Mwasapila, and he promises to make inquiries on my behalf. When he leaves, I have to remind him to take my contact information so he can follow up.

After the medical officer leaves, Jotham grins and says, “I do not think anybody with HIV will speak to you. These people do not like to talk about their condition. I am glad we had this conversation with the District Medical Officer. He is a better person for you to speak to than the hospital administrator because he is the official in charge.” “Maybe so,” I say, “but I did tell Madam Kashe at the Wasso Hospital we were coming today, and I promised to visit her. So I think we need to go there at least to say hello to be polite.”

Jotham counters, “We will not have time to go tonight, I think, since we will have to find a hotel and something to eat.” We check into a small guesthouse, and Jotham negotiates the price from fifteen to ten dollars a person. A man promises we’ll have hot water, which Jotham seems to really care about, and the man begins heating a barrel of water with charcoal. After an hour, the water is only tepid, and Jotham insists that we cannot go to find Madam Kashe until it’s hot enough to bathe.

My mobile phone rings: it’s Madam Kashe calling. “We are waiting for you here,” she says. “When are you coming?” I explain we’ve checked into a guesthouse and are waiting for hot water to clean off the grime of nearly two days of travel.

She asks me why I went to a guesthouse. “We have hot water here. And food, and beds.” It dawns on me that when Madame Kashe told me we would be welcome, she was inviting me to stay at the hospital, apparently in guest quarters. I apologize for the misunderstanding and hand the phone to Jotham. He speaks in Swahili for a few minutes and then hands the phone back. I say, “I think we made a mistake, and I really think we should go see Madame Kashe now.” Jotham surprises me by agreeing—maybe it’s the promise of hot water—and we wrap up in our warmest jackets and head into the suddenly cold desert night.

Madame Kashe greets us outside what appears to be a chapel and welcomes us inside where we find a table set with steaming food. A tall, baby-faced young man sits in a corner, speaking softly to another man and woman, both middle-aged. The young man comes over and introduces himself as Gedeon Omari, a doctor at Wasso hospital. Madame Kashe asks us about our trip and asks me what I think of Mwasapila. She makes it clear she is fond of the healer, but skeptical of his cure and adds, “I like how they’re taking care of Babu now! He seems much more energetic. He looked wasted before.” The food is delicious and Madame Kashe invites Jotham to take a hot shower in some other part of the compound, which he gratefully accepts.

After a long meal, when I think we may be preparing to go to bed, Gedeon addresses me directly. Speaking very softly, in English, he asks me what I’m hoping to achieve. I speak slowly and match his quiet tone. “I have heard about Babu, for many weeks now. And I’ve talked to many people who tell me they have been cured of minor ailments. But I haven’t spoken to anybody who has gone to see him for more serious conditions. Like cancer. Or HIV. So I want to talk to people who have and find out what their experience is.”

Gedeon introduces the other man and woman, who have said almost nothing. He explains they are his clients; both are HIV positive, both are taking ARV therapy. Each visited Mwasapila in November 2010, months before he became famous. After drinking the medicine, they stopped ARV treatment for a matter of weeks. Their CD4 count began to drop, so they resumed therapy. Both appear to be lucky—discontinuing ARVs can allow the virus to develop a resistance to the drugs—but both feel healthy after resuming their ARV treatment.

In the car on our way back to the guesthouse, Jotham clucks his tongue and tells me that neither patient seems to have strong faith.

The next morning, we meet Madame Kashe and Dr. Gedeon again, and this time I interview three patients. The first, Margaret, has type II diabetes, but her blood sugar has normalized since drinking Mwasapila’s liquid last fall. She also lost over fifty kilograms. Gedeon and Mama Kashe both suggest that she continue a low sugar, low starch diet. The other two patients have similar stories to the two I spoke with the night before, the difference being that they both have marginally improved CD4 counts.

Jotham watches the interview with decreasing interest from the side of the room, and when he steps out to make a phone call, I ask bluntly: “Do you know any HIV patients who went to Babu and got sick or died?” Gedeon tells me that just three weeks ago, a man from Wasso died. I ask if he was friends with either patient and it turns out he was the secretary of their HIV- positive support group. They say he was a good man and a friend.

His name, as it turns out, was Francis Tesha.

A few days later, I speak with Francis’ sister Flora over the phone and hear his full story. She tells me that shortly after Francis left the hospital in February, he was struck by another bout of opportunistic infections and left bedridden. He lost all hope. He couldn’t eat and refused ARVs. He coughed constantly from tuberculosis. Flora recounts, “We brought him the hospital on April 12, and this time, he did not get out until he died.” Now Flora tries to warn people away from Mwasapila. “You can’t stop someone from going to Babu, but the fact is that all of the people who went to drink the medicine regret it now. Many of them have died. I get so angry when I see somebody going there to drink that medicine.”

My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge …

—Hosea 4:6 (quoted in an editorial in a Kenyan paper, advising people not to visit Mwasapila)

On my second-to-last day in Tanzania, I meet with Dr. Paul Kisanga at Arusha Lutheran Medical Center. Unlike most Tanzanian hospitals, which could be movie sets for “A Farewell to Arms,” ALMC is a freshly painted steel-and-glass building, in which a director could film an episode of House. A large bronze plaque hangs on the wall with the names of dozens of donors, many of whom are Lutheran congregations in small towns in Minnesota.

Dr. Kisanga wears a dark, closely-tailored suit, and I notice an iPad on a stand in his office. He is gracious but obviously busy. Like the Wasso District Medical Officer, his answers are politic. He reminds me that his hospital is part of the same Lutheran Diocese as Bishop Laizer who has enthusiastically promoted Mwasapila and tells me, “As a medical scientist, I have no reason to think this works. However, we have a few people in the last three months with improved hypertension and blood sugars.”

He tells me about a formerly diabetic patient whose blood sugar has been normal for several months. “She is the wife of one of the staff here.” Kisanga makes a phone call and, a few minutes later, a white haired man appears in a black shirt, white clerical collar, and glasses—the Desmond Tutu look. He is Reverend Gabriel Kimerei, the hospital chaplain. Reverend Kimerei has known Ambilikile Mwasapila since 1974, when the former brick mason, not yet known as Babu, enrolled in a seminary program. Kimerei was his theology instructor. “He was a very quiet student. You wouldn’t know what he was thinking, but if you asked, he always gave you the right answer.”

Kimerei speaks near perfect English; he studied theology in Iowa in the 1960s. He is an enthusiastic believer in Mwasapila’s cure. “My wife has been tortured by diabetes for twelve years—swallowing the drugs every day.” Kimerei’s wife went to Samunge in February.

When she returned, she stopped taking her oral anti-diabetics. She eats a low-sugar, low-starch diet, and, according to Kimerei, “she is doing well, she is doing very well, but she checks her blood sugar every week.”

Kimerei acknowledges Mwasapila’s cure doesn’t work for everyone. In April, when Dr. Kisanga and other ALMC colleagues told him that some patients who abandoned medication were suffering, he proposed they take a trip to Samunge to speak to the healer. Kimerei says before their visit, the Ministry of Health tried to convince Mwasapila to instruct his visitors to keep taking their medications until they were sure they were cured. “He would not agree. He wasn’t happy about that.” But when Reverend Kimerei, Dr. Kisanga, and two colleagues spoke to him in April, he was swayed by his former teacher, and agreed to change his instructions.

It appears as of July, Mwasapila continues to honor the letter of the agreement, telling people they may continue taking medications, even though he says it will be as effective as “swallowing clay.”

According to Reverend Kimerei, there are a half-dozen HIV positive patients in the local Lutheran Parish who are completely cured. His colleague, a local minister, says they have already tested HIV negative. Kimerei graciously begins making phone calls and an hour later, he has arranged for me to meet with an HIV patient who has recently tested negative. She is going to re-test tomorrow at the hospital, and I am invited to witness the test.

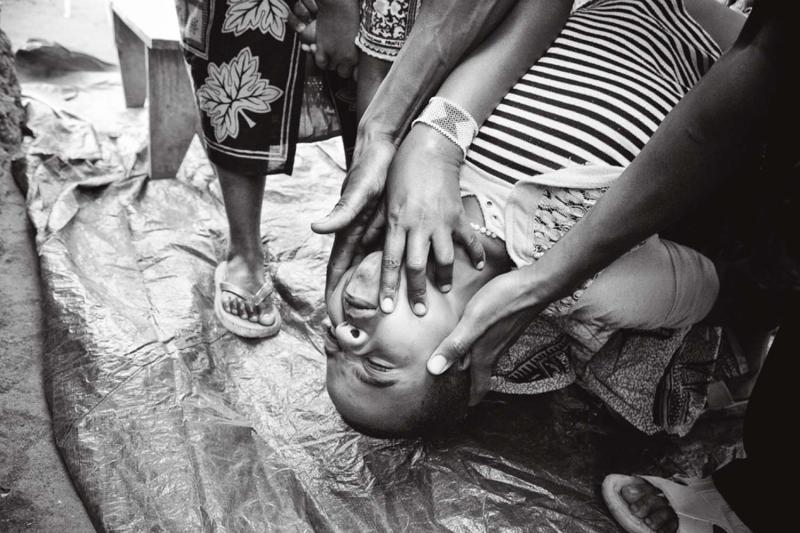

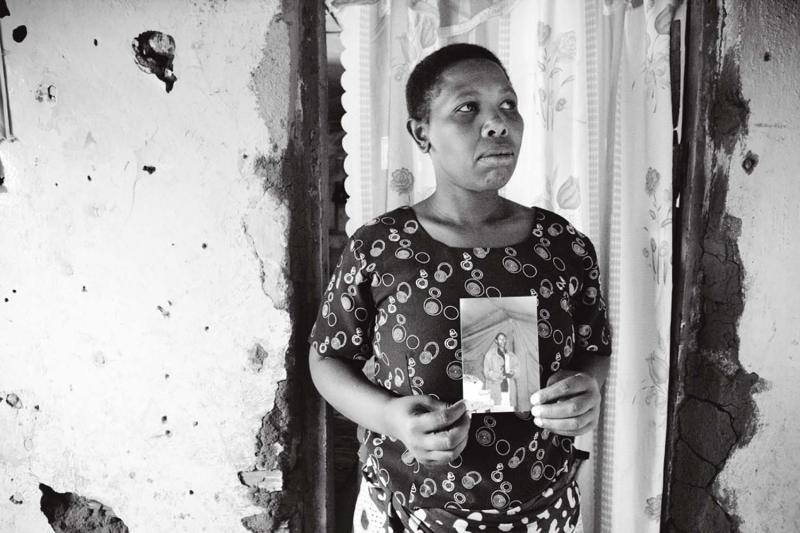

The next morning, Reverend Kimerei and I drive to the church to pick up a girl who looks about sixteen. She wears a green t-shirt and khanga—a skirt made from decoratively printed fabric— and she keeps her eyes to the ground. I introduce myself and she asks me, through the translator to change her name, so I will call her Alma.

We drive back to the clinic, where a female doctor takes us to a small room. I take a seat next to a cardboard box labeled hiv prevention— condoms. The doctor introduces herself, saying, “I’m Lucy, or Sister Mulingi” in Swahili, and introduces another man and woman, who are apparently counselors. She asks a series of questions, which Alma answers in a soft voice.

Alma first learned she was HIV positive in 2005 but has probably had the virus from birth. Her father died in 2001, and she lives with her mother, who is also HIV positive. Twice a day, she takes ARVs issued by the clinic, and she has never stopped, even after visiting Mwasapila. Sister Mulingi asks, Does anyone, any friends at school know about your problem?

No.

That’s good—we must help you avoid discrimination. Did you go to Samunge?

Yes, I went to Samunge in March.

After you came back from Samunge, did you take another test?

No.

But based on your belief you hope that you’re healed?

Yes.

Would you like that we establish your status at this moment?

Yes.

There are two possible results. The first result could show that your blood is still infected with the HIV virus. The second one could show that there are no traces of the virus in your blood; that would mean you’re cured. If it comes out without traces of the virus I’ll be very happy.

Sister Mulingi takes Alma from the room to administer the blood test. A few minutes later she calls Reverend Kimerei and me into a larger room.Alma is sitting on an examination table, and I sit next to her. Also in the room is a male doctor, the two counselors, and the translator, Jackson. Sister Mulingi stands in the middle of the room and then announces, dramatically in English, that the test results are positive. Alma still has HIV. She repeats the results in Swahili for Alma who nods her head slowly. The male doctor explains that at this clinic, they have tested over a dozen people who have been to Samunge and all of them are still HIV positive. Reverend Kimerei furrows his brow and says, “That is strange because the volunteer I spoke to said she was tested and she was told she was negative.”

I ask Alma how she feels about the test result. She answers very quietly in Swahili. I feel just fine. I was just fine before, and I am still OK.

I can’t say for certain that Mwasapila’s cure doesn’t work. I can say that every account I heard about somebody being cured by Babu of HIV/AIDS turned out to be either impossible to verify or verifiably untrue.

Two doctors at separate hospitals confirmed they had multiple patients who, like Francis Tesha, went to Samunge, stopped taking ARVs, and got sick and died. Pat Patten estimates that several hundred people have died that way, and based on my small sample, his math seems conservative. Perhaps the number would be higher if Reverend Kimerei and Dr. Kisanga hadn’t insisted Mwasapila allow patients to continue taking Western medicine.

On the other hand, there were numerous accounts of people claiming to be cured of stomach ulcers, aches and pains, insanity, and even diabetes. Multiple people echoed Dr. Kisanga in saying they had patients whose blood sugar had normalized after taking Mwasapila’s medicine.6 It is tempting think of the hundreds of thousands who visited Samunge as dupes, but many clearly felt better after taking the cure. And while I certainly didn’t find anything to support Mwasapila’s claim of a cure for HIV/ AIDS, it took three weeks of intense effort— and a cultural background that predisposed me toward skepticism of faith healing—to feel secure in discounting Mwasapila. Most Americans wouldn’t spend three weeks investigating the widely believed claims of their respected family doctor. We trust our appointed healers, and Tanzanians trust theirs. After Alma’s HIV test, Revered Gabriel Kimerei was troubled to hear so many people continued to test HIV positive, and embarrassed to have passed on bad information“That embarrassment is to his credit,” Pat Patten tells me over the phone, Patten considers many Tanzanian leaders to be complicit in a prolonged series of exaggerations—if not lies. In a June newspaper editorial, he wrote about the profiteering of the bus, truck, and taxi drivers, as well as the entrepreneurs and builders who found business booming because of Mwasapila. He noted that the government charges a hefty tax to all vehicles bound for Samunge, and the Lutheran Church leaders “can now claim that one of their own, not a Pentecostal, is the preeminent religious healer in the country.” Many government officials had chosen to stake their reputations on Mwasapila’s cure and risked embarrassment if they were shown to be wrong. “All sorts of people benefit from these lies,” Patten wrote.

But the voices promoting Mwasapila seem to have fallen silent. In the months since I left Tanzania, Patten says Mwasapila’s popularity has steadily declined. The Health Ministry still hasn’t issued the results of their study about the liquid, and the Lutheran Bishops are no longer talking about the healer. “They ought to be embarrassed and ashamed,” Patten tells me, “and I think they’re hoping people will just forget.”

I haven’t been able to reach Reverend Kimerei to ask about his wife or what he thinks now, but I have spoken to a friend—a safari driver who took three carloads of patients to Samunge in March and April. He was convinced Mwasapila’s liquid worked back in the spring, but he now says nine out of ten Tanzanians discount Mwasapila’s medicine. People may have felt better for a few weeks, he says. “But nobody who went there was cured. Not one.”

Research assistance provided by the Investigative Fund of The Nation Institute.