On the train out of London King’s Cross toward Bridlington via Doncaster one cold gray morning this past January—on my way to visit with David Hockney once again, this time regarding his upcoming San Francisco show of portraits and landscapes—I was watching the snug small towns and winter-idled fields stream by, punctuated by the occasional copse of bare trees, and I found myself recalling some lines of W. H. Auden’s that David used to cite when we were first getting to know each other (around the time of his Polaroid collages in the early eighties). A crisp vivid stanza from Auden’s “Letter to Lord Byron,” to be exact:

To me Art’s subject is the human clay,

And landscape but a background to a torso;

All Cézanne’s apples I would give away

For one small Goya or a Daumier.

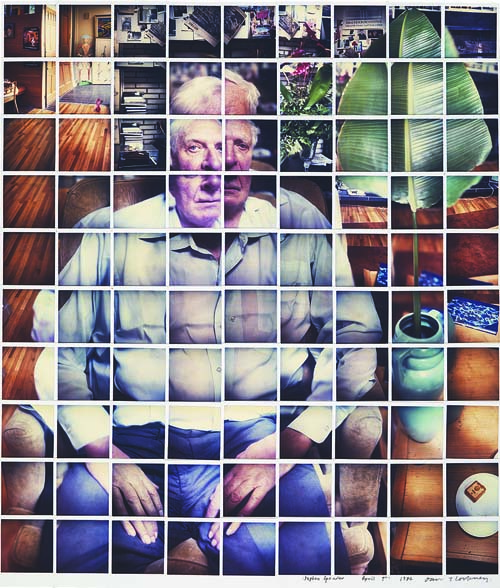

How he loved decanting those lines as he splayed out the Polaroid tiles into yet another portrait of this or that other fond dear friend—his studio assistants David Graves and Richard Schmidt and Gregory Evans, for example, or his longtime sidekicks Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, or Billy Wilder and his wife, or Stephen Spender by himself—commenting on the amount of time and focus it took to work out that room-wide backdrop if he were going to succeed in bringing out the piece’s true subject and his heart’s true passion, which was to say all that human clay.

How remarkable, I found myself thinking, that over the past ten years, the culmination in many ways of a passionate journey of aesthetic inquiry that had really begun with those gridded Polaroid collages, so much of the work had come to focus on an engagement with landscapes entirely emptied of any people.

As the train now began to home in on its coastal East Yorkshire Bridlington terminus, the thus far relatively bland landscape began to take on character. It began, that is, to look like “a Hockney.” And no wonder—scores of David’s watercolors and paintings and blown-up iPad drawings of these very wheat fields and sloping wolds and tight-grouped stands of trees and blowsy cloudscapes had recently held center stage at the Royal Academy in London. (A record 650,000 rapt visitors had traipsed through the gallery-wide exhibition, which then went on to draw similarly unprecedented crowds in both Bilbao, Spain, and Cologne, Germany.) Someone in London had commented that Hockney had managed to turn this previously ignored corner of East Yorkshire into a virtual national park, so familiar had people become with this particular vantage or that particular view, and so treasured had those views in turn become. Indeed thousands of people had started making pilgrimages to the environs of this otherwise fairly dilapidated onetime summer coastal resort situated across the North Sea from northernmost Holland. Having been noticed, the landscape sliding by—the dendrite-spreading trees, the sky-reflecting puddles, the dense brambly hedgery—began to look worthy of notice. No longer bland, it seemed to take on promise, veritably to breathe it out. “Look at me,” it seemed to boast (not unlike certain fields outside Arles on other hillscapes in the lee of the Montagne Sainte Victoire east of Aix), “look at me, for I have been seen.”

David was there to greet me in the parking lot at the Bridlington Station, all bundled up, smoking, snug in the driver’s seat of his Lexus sedan. He was, as I had been forewarned, somewhat less voluble than usual. Granted, over the years he has seemed to follow a regular, almost tidal, pattern: five or six years of intense and ever more intense activity (and the past half-dozen years had seen perhaps his most intense productivity ever), followed by several months of almost prostrate collapse. Only this time, as I was now given to understand, things had been a bit more serious than that. In fact, within weeks of each other, he’d suffered a minor stroke that had initially left him almost unable to speak, though his thinking and ability to draw had gone largely unscathed, and then four nights in a hospital for a substantial operation to clear some arteries in his neck. (It was the first time in his seventy-five years that he’d ever undergone anesthesia, let alone spent the night in a hospital!). His ability to speak seemed to be filling back in, and doctors were predicting he’d soon recover completely, but his discourse that weekend was still somewhat more halting than usual, and the experience—a brush, after all, with mortality—had clearly left him fairly shaken.

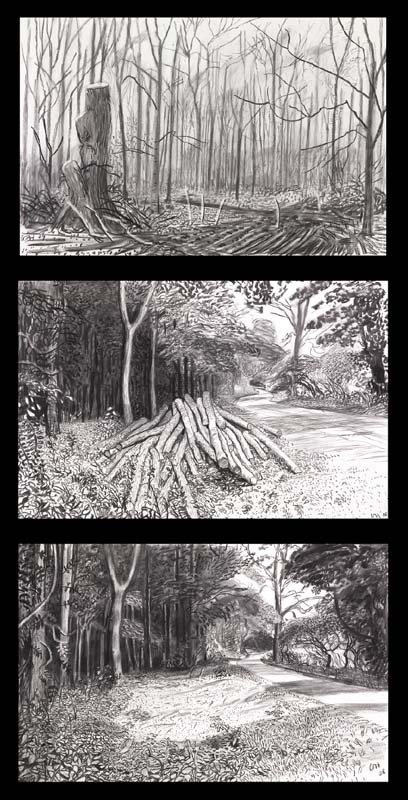

But what had really upset him, I now came to understand as he took me on a short side trip down the Woldgate Road just outside town (the undulating, tree-dappled two-mile country lane that constitutes the spine, as it were, of Hockney National Park), was something altogether more savagely unexpected. As I say, those of us who have been following Hockney’s landscape passion over the past decade, or else have re-experienced it across the recent museum shows, have gotten to know many of these swerves and swells almost by heart. We recognize this thistle-choked hedgerow along the roadside here, for example, or right over there, the leaf-tramped paths perpendicularly bisecting the road, the spot where David used to set up his easels season after season back in 2006–2007 as he built up the nine separate six-canvas combines portraying the changing play of air and light, month by month, across the spreading forest floor. And then, coming up here, the stretch of timberland thicket that was thinned out the following year, in 2008, the felled logs dragged out onto the roadside and stacked in piles, subject of countless drawings (indeed some of the most poignant pencil drawings of Hockney’s entire career, especially a sequence capturing the hauntingly emptied expanse once the felled trees had been removed), as well as a whole suite of epic color-besotted oil paintings. And now, round this next bend, yes, we’d doubtless see the Totem, as David called it, the person-tall magisterial tree stump by the side of the road that Hockney had convinced the foresters to leave standing and that over the years had become one of his favorite subjects. Only—wait, where was it? It wasn’t there! Where’d it gone?

David pulled the sedan to a stop and lit up a cigarette, allowing me to take in the full dimensions of what had happened: somebody, probably more than one somebody, had come along and simply toppled the thing, sawn the main body clean through a foot or two from the ground, abandoning the felled bole where it had come crashing down. “Vandals,” David muttered, exhaling a drag. “I mean, the sheer meanness of it all.”

He restarted the car engine and we headed back toward town, David relating how shortly after his little stroke, while he’d been down in London getting checked out, a group of pranksters one night had apparently defaced the famous Totem, slathering hateful graffiti all across its flanks in gaudy, bright pink paint—the image of an erect phallus at waist height, the word “CUNT” in a sloppy scrawl. David’s own crew had been hesitant even to tell him, though in the event he hadn’t proven all that upset, figuring that the coming rains would wash the vileness away. But then a few weeks later, in the period following his operation while he was in the hospital, the hooligans had apparently come back in the middle of another night to chop the whole thing down. “You could see,” he now said, “it can’t have been an easy thing to do. It was quite thick there at the base. Must have taken a good hour and involved at least two of them.” Again David’s crew had hesitated to tell him; he only found out on the Monday of his return. Shattered, he withdrew to his bed and didn’t get up for two whole days. “Very dark,” he now intoned. “I felt about as bad as I have in many years. Why would anyone do something so spiteful?” That Thursday, though, he’d climbed out of bed, newly resolved, and headed back to the scene, sketchpad in hand. “I couldn’t really speak still,” he now recalled as we turned onto his side street. “But I could draw, and I could even concentrate.” And over the next three days of intense concentration, he’d proceeded to produce five charcoal drawings of his felled hero.

He now eased the sedan into the garage of the onetime bed-and-breakfast he’d originally bought as a residence for his then-nonagenarian mother (and into which he and his studio crew had moved in the wake of her passing, at age ninety-nine, back in 1999), and we made our way into the lodging’s cozy kitchen (“cozy” having been a favorite word of Auden’s as well), where David showed me reproductions of the five drawings. “The people at the Guardian heard about the tree’s having been chopped down—word of the event made it down to London” (the Totem had been one of the standout stars, after all, of the previous year’s Royal Academy show, its image plastered all over town), “and they called up to ask if I had any comment. In response, I e-mailed them images of some of the drawings”—David rummaged around piles of old papers, spearing a copy of the daily—“and, see, they put it on the cover.” Indeed they had, and above the fold at that, with a whole other spread on the inside. Major news. Hard to imagine anything like that happening in the United States. Who was it—Ezra Pound?—who described poetry as news that stays new? On the other hand, famously, conversely, as William Carlos Williams noted in his “Asphodel,” “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.”

Mortality, of course, being of the essence here. Surely Hockney’s brush with his own mortality must have intensified the pall of his response to the assassination of that Totem, whose resolute survival after the thinning out of all the other logs piled there by the side of the road, piled and then hauled away, must over the years have come to stand, in no small measure, for his own unflagging productivity. His drawings and paintings of the Totem across the ensuing seasons hadn’t been landscapes at all, I found myself thinking later that evening as I prepared for bed, recalling the Auden riddle I’d thrummed at on the train ride up; if anything, they’d been portraits. And self-portraits at that. How else to account for the uncanny power of those drawings of the Totem felled, drawn in the wake of his own near-brush with death?

Still later, falling off to sleep, I came to realize that, in fact, the distinction between landscape and portrait at the heart of this coming show, at least as it pertains to Hockney’s work of the past several years, might itself constitute a kind of mischaracterization. For Hockney’s weren’t landscapes in any conventional sense. Rather, they were portraits of the land, and not just any land—land that David himself had worked as a teenager on summer stints out of nearby Bradford, land across which his mother’s very ashes had been scattered. They were careful studies of the way light and the seasons played across the face of the land, rendering the vistas ever more familiar and cherished. And for that matter, conversely, the more conventional portraits in this coming show, repeated returns year after year to gaze upon the same dear friends, might in their way be seen as landscapes—careful, care-saturated studies of the weathering of face, bearing, and posture across the years (of course the tradition of portrait as landscape goes a long way back in the Western tradition; think of the great wide horizonscape of Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus). Indeed, the landscapes and portraits alike might better be understood as timescapes, studies of time’s passing, and as such, evocations of the evanescent preciousness of life.

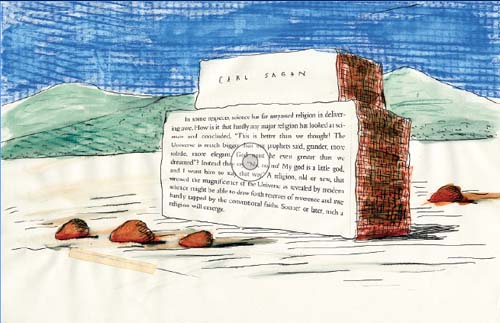

At one point, sometime in the early nineties, Hockney took a paragraph from the astronomer Carl Sagan’s book Pale Blue Dot, photocopied it, embedded the text in a simple color drawing of a plinth-like monolith dominating a rock-strewn plain, and proceeded, as was his frequent wont, to mail copies of the image to several friends. “In some respects,” the plinth’s text read,

science has far surpassed religion in delivering awe. How is it that hardly any major religion has looked at science and concluded, “This is better than we thought! The Universe is much bigger than our prophets said, grander, more subtle, more elegant. God must be even greater than we dreamed”? Instead they say, “No, no, no! My god is a little god, and I want him to stay that way.” A religion, old or new, that stressed the magnificence of the universe as revealed by modern science might be able to draw forth reserves of reverence and awe hardly tapped by conventional faiths. Sooner or later, such a religion will emerge.

Across the bottom of the version he sent me, he’d hand-scrawled, in the lower right-hand corner of the image, a simple injunction: “Love life!”

I say timescapes, but what I mean, of course, are lovescapes.

Now, I’m not in any way suggesting that Hockney fancies himself Moses-like, the founding prophet of some new-age religion. But the thing that stands out in that Sagan passage, looking back on it now, is the precision of its characterization of the challenge—the need to break free from impinging orthodoxies, to reach for bigger and grander ways of being in the world; the way in which, as Hockney himself soon started insisting with ever greater urgency, wider vantages are called for now.

As it happens, Sagan died just a few years after penning those lines, and what might have initially read, in Hockney’s rendition, as a rousing monolithic assertion came, with the passage of time, to seem more like a tolling memorial headstone. Likewise, I’ve recently come to feel, with the whole sweep of Hockney’s production across the latter half of his career, starting in the early eighties with those Polaroid collages. Elsewhere I’ve attempted to evoke the dead end before which David had seemed to arrive toward the end of the seventies: how two Golden Boy decades in which he had seemed incapable of doing any wrong had culminated in that series of extraordinarily successful double portraits—from Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott in 1969, and Celia Birtwell and Ossie Clark with their cat in 1971, and Peter Schlesinger gazing down on that swimmer poolside in that 1972 hillscape, on through the remarkable portrait of his parents from 1977 (his mother to one side, peering intently out at him, his father hunched off to the other, seemingly lost in the perusal of an art book spread across his lap). Hockney could have easily gone on knocking off that heightened realist sort of thing for the rest of his life, and doubtless his dealers would have loved him for it; they were instant classics. But something was gnawing at him all the while, already discernible in one of the first in the series, Le Parc des Sources, Vichy of 1970 [in which two friends seen from behind on plastic chairs, a third empty chair by their side from which David had presumably only just risen, gaze into a pair of vertiginously tapering tree colonnades to either side of the canvas, and then all the way through the ridiculously ambitious and presently abandoned view out across the street from the inside of his studio on Santa Monica Boulevard (1979)]. The problem being, as he would come to see it, the tyranny of one-point perspective. Thus, Hockney’s increasing fascination, there toward the end of the seventies, with cubism in general and Pablo Picasso in particular (especially the late Picasso)—the way those artists too had been wrestling with the same problem. And thus, also, the origins of that Polaroid passion, starting in February 1982, in which he was consciously trying to break the picture plane into multiple one-point perspectives, the goal, already there, being to reach out toward wider and wider vantages.

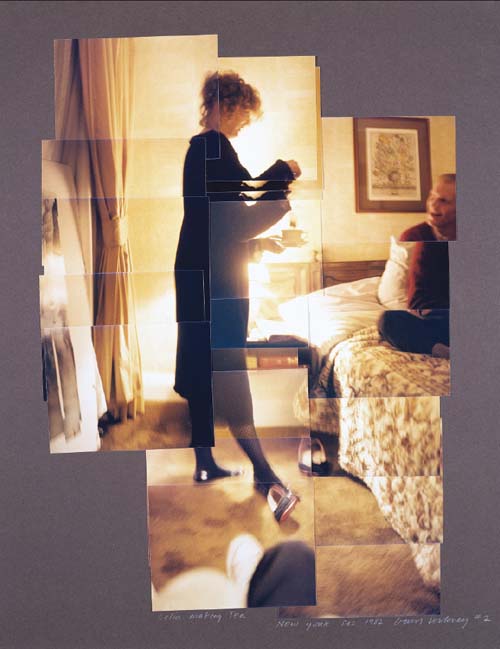

But the thing of it was, I now realized with a start, what else had been going on in the early eighties? Googling, I confirmed that April 24, 1980, had seen the recognition of the first case of AIDS in the United States, when Ken Home, a San Francisco resident, was reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as presenting with a previously rare cancer known as Kaposi’s sarcoma. On July 3, 1981, the New York Times ran an article headlined “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” the first such piece on the subject; by the end of 1981, 121 people had died of the disease. Hockney fashioned his first Polaroid collage, a tour of his Hollywood Hills home, on February 26, 1982, going on to assemble dozens more such collages, mainly portraits, over the next several months. On July 27 of that same year, just around the time Hockney was beginning to make the transition from those gridded Polaroid combines to the more seemingly pell-mell borderless Pentax photocollages, the term AIDS (“acquired immune deficiency syndrome”) was first proposed at a meeting of gay leaders and federal health bureaucrats in Washington, DC, as a replacement for the previous term GRID (“gay-related immune deficiency”) as evidence was beginning to percolate that the illness was not confined entirely to gay men. And indeed, on December 10, 1982, a baby in California became ill with the first known case of AIDS contracted from a blood transfusion. That same month, Hockney crafted a major photocollage documenting a visit to the New York City apartment of his longtime friend and model, Joe MacDonald, who had recently fallen mysteriously ill. And soon thereafter he made another one, showing their mutual friend Celia in hauntingly backlit dark silhouette preparing a cup of tea for Joe, who is seated on his bed, one of the first such combines in which Hockney tries to interject the experience of movement: Celia’s arm pulling the tea bag out of the cup and shaking out its last drips.

By the following year, Hockney, still fancying himself young and blithe at age forty-five, would start seeing close, dear friends from his young blithe cohort dying all about him: Joe, Nathan, René, Charles, Mario, Larry, Nick… . And not just of AIDS. Over the ensuing years he would lose two of his closest friends, Henry Geldzahler and Jonathan Silver, to savagely premature deaths by cancer, and then, by century’s end (albeit at the other age extreme), his mother.

The point is that Hockney’s entire production over the three decades since 1982 has been shadowed by death and in many ways can be seen as a direct response to all of that dying—a defiant celebration of life (“Love life!”) in the face of annihilation, the assertion of an almost aching tenderness in the very craw of mortality. (Think for instance of that remarkable suite of paintings and pencil sketches from the late eighties and early nineties of his beloved dachshunds, Stanley and Boodge, as they lie there lolling and lazing and nuzzling voluptuously, this at a time when it was no longer really possible to render similarly uncontaminated vantages of young male nudes.) Life against death. Light against death (that glorious soaring final exaltation of pure blue light, cresting and cresting at the climax of the “Liebstod” in Hockney’s late staging of Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde). And finally, really, simply love (“Love life!”)—love against death.

But it’s also clear that across the past three decades, the assertion of life and love against death has become synonymous in Hockney’s mind with breaking that constrictive, tapering, ever-narrowing stranglehold of one-point perspective. In retrospect one begins to notice intimations of that coming passion already in the seventies. See the way, for instance, he chose to portray Bedlam in his 1975 production of the Stravinsky/Auden Rake’s Progress at Glyndebourne—not as in virtually every other production of the opera or any other such representation of an insane asylum you’ve ever likely seen (from William Hogarth through Tennessee Williams, from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest through Sweeney Todd), as a seething, roiling mass of demented humanity, but rather as a grid of nested cells, each containing an isolated inmate, tapering relentlessly to the back of the hall. Perspective itself, that is, as a form of madness. With Hockney’s subsequent delving into Chinese painting (with its moving focus) and quantum physics (with its liberating tolerance for ambiguity), his critique of the dead hand, the death grip (as he was now coming to see it) of one-point perspective, started becoming more and more overt.

The same goes for his entire photocollage adventure, which, far from being a celebration of photography (as some took it at the time, a retreat from painting into the higher potentialities of the photographic), constituted one long attack on ordinary photography, pervasive as its presence had become (everywhere from billboards to magazines to television and the movies), or at any rate on its standard hackneyed claims to being capable of representing lived experience in any meaningful way. “Photography is all right,” Hockney liked to say, “if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralysed Cyclops, for a split second.” He’d pause, waiting for the image to sink in. “But that’s not what the world is like, and it’s not what actually experiencing the world is like.”

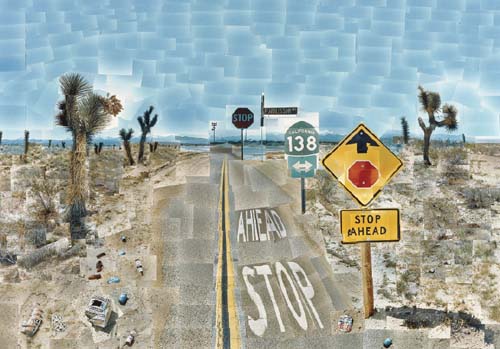

Trying to depict the world as it is actually experienced, or more precisely to capture the experience of advancing into all that space, now became the animating focus of Hockney’s work. At first a series of climactic photocollages allowed, encouraged—frankly, even compelled—viewers to break free from the constraining vise of one-point perspective and instead to let their eyes wander across multiple simultaneous vantages: Pearblossom Highway, for example, with the seamless interweaving of its attention both to the close-up and the far-off; or The Desk, wherein, by following the cubists’ lead and reversing perspective, Hockney was able to bid the viewer to move all about the object of regard, seeing it from one side and then the other or both sides at the same time. These were, in turn, the sorts of effects Hockney explored further when in January 1986 the editors of French Vogue gave him free rein of their pages as guest editor. And they likewise circulated back into his paintings of the period, as, for instance, in A Visit with Christopher and Don, Santa Monica Canyon of 1984 (in which the viewer was invited, as it were, to drive up to the house, park the car, climb the steps, enter the home, and walk about from room to room, repeatedly glimpsing the same and yet not quite the same vista from different windows). All of this culminating in that sequence of ever more ambitious depictions of the view out over the Grand Canyon from the very edge of its rim (way out across to the other side, down into the abyss, and then back up the near flank across a sequence of various side-croppings)—talk about space!

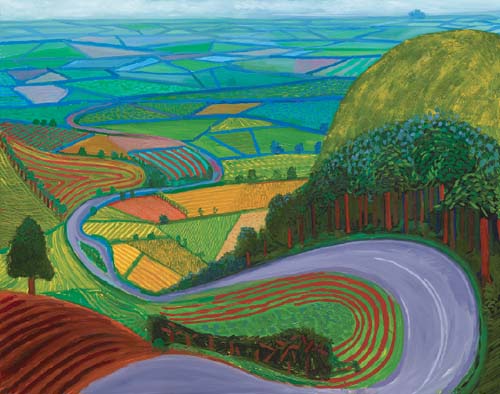

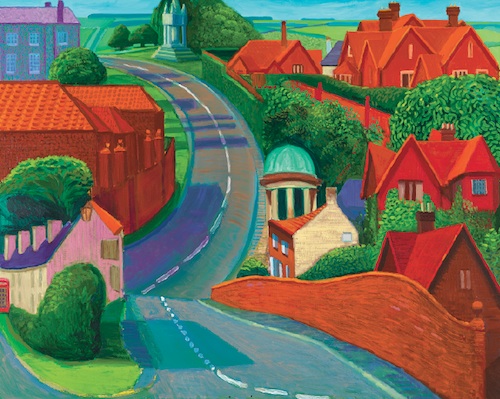

This layering of space upon space, the stacking of horizon upon horizon in the same image, in turn seemed to reach a further crescendo in the series of paintings Hockney embarked upon some years after that, when he was back in England for the first extended period in years. Traveling back and forth between his aging mother’s place in Bridlington and his ailing friend Jonathan Silver’s final sickbed in a hospital in York, he now began portraying the land and villagescapes of Eastern Yorkshire for the first time—on The Road across the Wolds, for example, or The Road to York through Sledmere. Perhaps most impressive of these early efforts is the view from atop Garrowby Hill, where as the highway crests the peak, the sudden vista of the entirety of the York valley suddenly heaves into view, in soaring reverse perspective (you can almost feel how, though the back wheels have yet to quite make it over the hilltop, the front wheels of the car are already barreling forward into the downsloping view).

Wider and wider perspectives: for that has been the leitmotif of all of Hockney’s work there outside Bridlington over the ensuing decade and a half—the period that will form the focus of the coming San Francisco show. Wider and wider, even when the subject becomes more and more constricted, sometimes just to the play of light upon a passing hedgerow, or the fields peeling off to the sides from an off-center tunnel running through a copse of trees. Wider, too, the passage of time, the turning seasons, all the lush liveliness that comes and goes and comes again, nature that abides.

The weeks passed after that last Bridlington visit, I was back in New York but would check in with David by phone every once in a while, and his capacity to speak definitely seemed to be filling back in. In addition, he was now sending out a fresh stream of images: photos of new drawings on paper, portraits once again, a fresh inventory of his crew and friends and all the love that still remained. They were rendered in the rich blacks and layered shadings of charcoal—a carryover from some of his recent landscape work, notably the felled Totem studies. An almost literal carryover, it further occurred to me; for here we had images of beloved companions captured by way of the burnt wood of charcoal applied across the pulped wood of paper. There was, furthermore, an almost autumnal cast to many of the drawings, images of subjects we ourselves have watched age over the years right alongside David, thanks to David. This was most poignantly the case, perhaps, in the portrayal of a decidedly more weathered and haggard Maurice Payne, whom David has been sketching for almost half a century now, but also in the images of some of his younger sitters, who likewise seemed to be leaving their youth behind. And then, too—was one perhaps reading in too much?—the sitters themselves with the steadiness of their outward gaze seemed to be taking in the way David himself was aging before their eyes. Not necessarily in any morbid way—consider in this context, the marvelous gleam persisting in the gaze of David’s ever-spry sister Margaret (the wisest of us all, the portrait seems to suggest)—but with calm and sober lucidity. This being the arc of our lives.

Landscapes and humanscapes, as I say. Timescapes, lovescapes: lifescapes. All of us—people, trees, fields, hedgerows—in that sense, being of a piece, beauty past change. And yet, not. For as Franz Wright observes, in his poem “The Knowers,”

Little bird bones come back

as a bird, as a bird

loudly singing

again

in the dead leaves

come back as green

leaves: only

we

don’t return.

The analogy breaks down. For in the end, people in fact aren’t like fields or birds or trees. Or at any rate, we ourselves are not. As Wright reminds us, we know.

“I don’t know,” David commented at one point during one of our recent phone conversations about something or other, I don’t remember what. “I don’t know.” He paused, thrumming (I imagined him taking a drag on his cigarette). “I find myself saying that a lot more often these days: I don’t know. I don’t know,” he continued. “And yet that’s okay. It doesn’t bother me. I can live with it.”

One can not know and still wonder—be susceptible, that is, to wonder, to marvel. Still capable, to the very end (Auden-like), of cele-bration and praise.