At the beginning of this year I drove from New York City to Iowa City, where I had a semester-long post as a visiting professor at the University of Iowa. My midpoint stop was Oberlin, Ohio; an old friend who teaches in the music conservatory at Oberlin College had offered to put me up in the spare bedroom of his apartment near the campus. It had been a rather harrowing day of car trouble and bad weather and after ten hours on the road I was frazzled and hungry and a little spacey. On our way to dinner, my friend and I stopped at the local IGA supermarket to pick up some breakfast items. In the dairy aisle, I turned around too quickly and bumped a woman behind me.

At the beginning of this year I drove from New York City to Iowa City, where I had a semester-long post as a visiting professor at the University of Iowa. My midpoint stop was Oberlin, Ohio; an old friend who teaches in the music conservatory at Oberlin College had offered to put me up in the spare bedroom of his apartment near the campus. It had been a rather harrowing day of car trouble and bad weather and after ten hours on the road I was frazzled and hungry and a little spacey. On our way to dinner, my friend and I stopped at the local IGA supermarket to pick up some breakfast items. In the dairy aisle, I turned around too quickly and bumped a woman behind me.

By “bumped” I mean the kind of miniscule collision that happens countless times a day, especially on days like that, when the temperature is in the single digits and bulky parkas leave everyone taking up more space than they realize. What I mean, essentially, is that my puffy coat tapped the other woman’s puffy coat. Or maybe my puffy coat tapped her shopping cart. Or maybe the shopping basket I was holding briefly clanked against her shopping cart—or grazed her puffy coat—as I passed. Memory is tricky. I was in mid-conversation with my friend in that moment and though I wouldn’t swear under oath as to the exact nature or extent of contact, I can tell you that as someone who is perennially on guard against seeming rude or taking up too much physical space, whatever I did was about as unintentional as it gets. As such, I issued a rote “excuse me” and kept walking.

“Did you just say excuse me?” the woman asked from behind me.

“Yes, I’m sorry,” I said, instinctively elevating the pitch of my voice the way women tend to do when they want to avoid conflict.

“You’re not sorry,” she said, her voice not elevated. “I’m invisible to you. You did not see me because I’m invisible to you.”

The woman was middle-aged and African American. Like me and just about everyone else in the store, she was wearing a bulky parka. I opened my mouth to respond but she began shaking her head furiously. The implication was clear. I was not to speak. I was to be silent while she told me again that she was invisible to me. Not wanting to make a scene, I raised my hands in a mild gesture of surrender and walked away, my heart pounding.

As it turned out, the woman was a prominent professor in one of the humanities departments at Oberlin. Though of course I couldn’t be 100 percent sure what she was thinking, it seemed pretty clear that she had interpreted our little collision as a racist affront. At this, I was both mortified and infuriated. Over dinner, my friend and I rehashed the incident from numerous angles. Though he was aware of the social justice climate on campus, his conservatory students are mostly too busy practicing their instruments to join the ranks of the most vocal activists. As such, he was shocked by what had happened and we both puzzled over whether some kind of active response was in order.

On one hand, what was the point? The whole thing amounted to no more than eight seconds of discomfort in our otherwise exceptionally comfortable lives. Sure, it was possible that, as a professor at a college arguably considered the epicenter of the loosely defined phenomenon known as “campus identity politics,” this woman was exactly the problem when it comes to entire generations of students not being able to distinguish commonplace social friction from microaggressive bigotry. On the other hand, maybe she was just having a bad day. Maybe she, too, had just driven ten hours in bad weather. Or maybe, on the way to the supermarket, a careless driver who hadn’t seen her had cut her off in traffic. Or maybe being a person of color in rural Ohio brings about such feelings of social and cultural alienation that just getting through the day can be exhausting and, like it or not, spacey white people in the supermarket must sometimes bear the brunt of that exhaustion.

I decided to write her an e-mail. After several drafts, I settled on this:

Dear Dr. ___. I’m the person who inadvertently bumped you at IGA this evening. The intensity of your reaction has stayed with me. I was not looking where I was going and it’s true that I did not see you when I turned around. But you were not invisible to me. I was merely clumsy. Once again, I apologize.

I never received a reply. In fairness, the semester hadn’t yet started and maybe she wasn’t checking her e-mail. Also in fairness, the e-mail didn’t exactly demand a reply, since, let’s face it, I’d written it to myself as much as to her. I’d couched it as a quasi-apology, but really I wanted to let the record show that I was not racist. I wanted her to see how she’d gotten me all wrong. If I’m being honest, I also wanted to shame her just a little bit. Or a lot. But only because she’d tried to shame me. As with the encounter itself, there were a lot of ways to think about it.

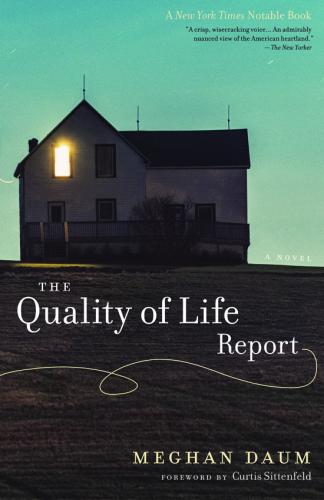

And I did a lot of thinking about it. That’s what happens when you’re driving nearly a thousand miles from east to west in a sixteen-year-old car with no iPhone jack and only a handful of mostly scratched CDs. It’s either country radio stations, AM talk, or the sound of your own thoughts. The trip represented a strange return for me. Nearly two decades earlier, I had moved from New York City, where I’d lived for my entire twenties, to Lincoln, Nebraska, where I lived for nearly four years. During that time I wrote a satirical, semiautobiographical novel called The Quality of Life Report. Published in 2003, the book is, among other things, a humorous dissection of the hypocrisies of a certain kind of liberal in a certain kind of midwestern academic town. It also shines a none-too-forgiving light on its narrator, a hyper-ruminative if also reflexively snobbish lifestyle journalist from New York named Lucinda Trout, whose search for some indefinable form of “authenticity” leads her into trouble (mayhem ensues and so on).

Written in a fury of taboo-defying feistiness, the novel leaves few cultural nerves untouched. The love interest is a charming train wreck of a man with an intermittent drug problem and a harried parenting schedule thanks to having three kids by three different women. There are lesbian farmers and soap opera–addicted grain elevator workers. There’s a boozy book club made up of earnest white women who fetishize black authors (there’s a Maya Angelou stand-in named Idabelle Sugar) and who delight in framing even the most mundane conversational topics into opportunities for feminist consciousness raising. Their only real life African American acquaintance is a bland and apolitical woman who prefers Harry Potter to feminist tracts. There are even passages of made-up prose attributed to the made-up Idabelle Sugar, deliberately over-the-top (in black dialect, no less!) and meant to poke fun at some of Angelou’s more grandiloquent tendencies. In the book’s most flagrantly ridiculous scene (which the publisher seriously considered asking me to take out) a lusty stallion stimulates himself to climax and ejaculates over a fence and onto partygoers attending a barbecue.

The book can be buffoonish and broad (for better or worse, I was reading a lot of John Irving the time) but I’ve never in my life had so much fun writing anything. I remember sitting in my chair during those years and at times practically falling out of it from laughing out loud. This is not a regular feature of my creative process.

Last year, after not having looked at the book for a very long time, I reread it and found myself laughing all over again. I also found myself utterly shocked by some of the content. Though the reviews back in 2003 had been mostly positive and, moreover, made little if any mention of the risky humor around things like race, class, and gender (or the political undertones of sexually irrepressible farm animals) the humor seemed to me by today’s standards to be something bordering on unacceptable. Were the novel to be published for the first time today (and I suspect it might not be) there’s a good chance it would be the target of such excoriation on social media and elsewhere that its fundamental message—that liberals can be the most illiberal of all, just as urban coastal types can be the most provincial—would be dismissed as irrelevant, if not lost altogether.

I bring this up because the book has just been brought back into print after many years, a prospect that both delights and terrifies me. The delight and terror is made all the more urgent and surreal by virtue of the fact that I am back in the Midwest again—if only for a semester—this time surrounded not by boozy book club women but by various iterations of the professor I failed to see at the supermarket in Oberlin. Even here in the land of Big Ten sports, students are holding forth about intersectionality, imperialist capitalism, and the erasure of systemically marginalized groups. Kiosks and hallway bulletin boards are plastered with flyers for lectures, workshops, and other teachable opportunities pertaining to diversity, microaggressions, and the need to give voice and space to groups that have historically been denied their own voices and spaces.

More significantly, people of all ideological leanings contend with the daily macroaggression of our miserably polarized political climate. My students are stressed out and even frightened—not just about the Trump administration’s policies but about state budget cuts that roll back university funds and threaten their scholarships—and they fill much of their time outside the classroom calling their representatives and lobbying at the state house in Des Moines. Inside the classroom, I sometimes notice stress and fear being played out in the form of a need to control the way we talk about certain subjects, especially those related to race and gender. Too often I hear them needlessly apologizing before they speak. Too often, I hear myself about to do the same.

Media hand-wringing about radical campus leftism and postmodern theory run amok has practically become its own genre of cultural commentary. The commentary is often grossly oversimplified and yet is consumed ravenously by aging liberals who bristle at the thought of being perceived by youngsters as fusty conservatives. I count myself among those liberals. I hate the sanctimony and literalism endemic to some parts of social justice culture, for instance the apoplectic reactions to minor missteps, the seemingly willful aversion to nuance. Frankly, I hate even more the way the media often panders to this sanctimony and literalism because it knows this is where the clicks are. But I don’t think my students are necessarily wrong about everything, or even most things. The truth is that many of them are frighteningly smart and well read, so much so that I often leave class in a head-spinning vortex of self-doubt and confusion: maybe writing about anyone other than yourself is appropriating another’s experience, maybe gender is merely performative, maybe I really am just not getting it.

In The Quality of Life Report, the town of Prairie City (PC for short; get it?) functions in part as a laboratory in which the narrator, Lucinda, can test out her half-baked social theories about what counts as “sophistication” and to what degree this sophistication stands in the way of an “authentic life.” The novel is set in the early aughts, a time when being sophisticated, at least by the coastal elite standards of someone like Lucinda, meant repudiating the political correctness of the late 1980s and early 1990s (think Take Back the Night marches and the first wave of campus speech codes). It meant being so comfortable with your liberal credentials that you could flaunt that comfort by being decidedly un-PC. But what Lucinda takes too long to understand is that in places like Prairie City, the ethos of late-eighties and early nineties political correctness didn’t begin to show up until the early aughts. To people in midwestern liberal circles, the language of political correctness is still exciting and meaningful. That’s why her disparagement is ultimately so juvenile—something akin to hating a band the minute it gets popular.

In 2017, a lot of people, myself included, are reacting to social justice pieties the same way Lucinda reacted to the liberal pieties of Prairie City. As with Lucinda, sometimes our exasperation is warranted and sometimes we’re being stubborn and reductive for the sake of efficiency. At the same time, there are also lots of people fiercely and sincerely committed to those social justice pieties, not just in the spirit of performed outrage but because their ideas about dismantling systems of oppression include firmly held ideas about the words we choose, what we laugh at, and who is allowed to speak for whom. If the rerelease of The Quality of Life Report attracts new readers to the book, I am certain it will make at least a few of them angry and uncomfortable in ways that it rarely occurred to people to be angry and uncomfortable back in 2003. Some will surely posit that I, as a white writer, have no right to create the fictional prose of an imaginary black author. Others might see some of the more boundary-pushing humor as (to use the idiom du jour) “a violence.” (And I’m not just talking about the masturbating horse.)

Despite all the head spinning that accompanies me out of the classroom, I still reject both of those premises unequivocally. Not only do they discourage, if not downright outlaw, the kind of aesthetic and rhetorical high-wire acts that tend to excite me the most as both a reader and a writer, they also suggest that reading itself is some kind of exercise in patrolling for authenticity. Zadie Smith, who’s written from a variety of ethnic and gender perspectives, put it succinctly when she said in an interview last year that she “resent[s] the idea of being portrayed as such a vulnerable human that if you involved yourself in any aspect of my ‘culture’ I will crumble at the idea of you borrowing it from me.”

But as heartening (okay, validating) as Smith’s words are, I keep wondering what my encounter in the supermarket in Oberlin says about our collective vulnerability these days. Has our ability to tolerate discomfort—the literary kind as well as the day-to-day kind—melted away over the last decade along with the sea ice, leaving us feeling too fragile to ever again laugh at the things we used to laugh at, starting with ourselves? Or is there a more forgiving, less dogmatic spirit lying dormant somewhere inside all of us?

At this particular moment, my very considered opinion is hell if I know. What I’m beginning to understand, however, is that one of the most hopeful sentences in the English language can also be among the most frightening. It’s just two words long: Times change.