My niece named her second son Jordan. A magical name, she must have been thinking. A name to connect her son with Michael Jordan’s magic on the court, his fame and good fortune. A name with more in it than she or I or anybody could have guessed. Power to raise the dead in the name my niece chose. Power of the dead to raise the living.

For reasons that I am not proud of, I have lost track over the years of my niece’s Jordan. Haven’t keep up with MJ either. Except recently, a documentary, The Last Dance, whose subject is the vexed but ultimately victorious pursuit of a sixth and final NBA championship by Jordan and his Chicago Bulls teammates, revived my romance with MJ’s fabulous exploits, my hero-worship of him that verged always uncomfortably close to idolization, and thus inevitably tinged by envy, insecurity, vanity, unrequited love.

My niece’s Jordan was about six years old in 1998 when the Bulls danced off into the sunshine of eternal glory and MJ retired. By then I had met Michael Jordan and his fellow Bulls, written articles about them for national magazines, and basically lost touch with my great-nephew. We lived in different cities, and usually Jordan was in a swarm of other family kids when I saw him—smallish, his skin a few shades darker than most of the others, a bit shy and quiet. Beyond the fact that he loved turtles, liked reading and school, and never forgot to remind me that I’d promised all the kids a Christmas holiday in Disney World, he remained a cute little stranger. From his older brothers he had picked up the habit of watching sports on TV, pro football mostly, since everybody in Pittsburgh loved the hometown Steelers, but I had not noticed nor had anyone ever mentioned any particular aptitude or ambition that Jordan possessed to follow in MJ’s footsteps, to be like Mike, unless you counted the extra incentive that might drive a boy to achieve something special back then because his skin color was MJ-dark and marked him as a sort of outsider.

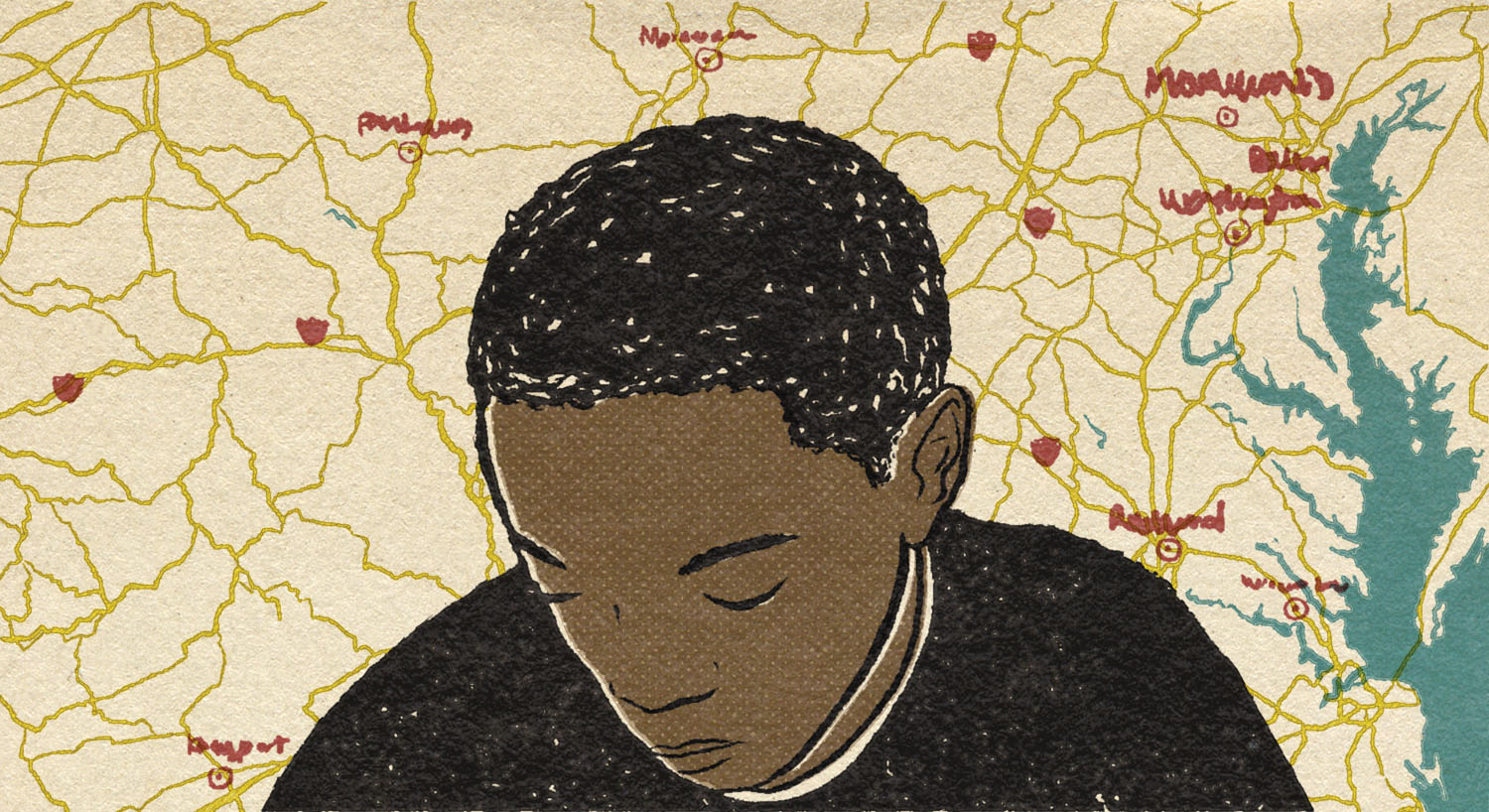

Jordan still resided in my niece’s belly in October of 1992 when I arrived in Pittsburgh to pick up my father and travel with him to Promiseland, a small, virtually extinct town in South Carolina from which, in 1900, my father’s father—my grandfather, Hannibal—had migrated to find work in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Going to Promiseland was long overdue. A return-to-our-roots trip I had promised my father and myself. Just as once upon a time I promised Jordan and the other kids a trip to Disney World. Grandpa was dead at least a decade, so he wouldn’t be accompanying my father and me on the journey I had originally envisioned for the three of us, and no time to spare, since my dad was clearly on his last legs, only question being: Which would fail him utterly first, body or mind? That powerful boxer’s body and swift hands, or that even swifter, tougher mind he had exhausted fighting every day of his life for the dignity and space that were supposed to be a guaranteed birthright (in theory, anyway) for all Americans? For my father, because color was a rule always there lurking behind the scenes—hidden sometimes, though sometimes definitely not—his life was a battle commencing each morning to find self-respect, fighting for room to breathe from the moment he opened his eyes till he closed them at night. A tiresome, wearying, consuming struggle he waged daily to endure.

Never got round to a Disney excursion with Jordan, and almost lost the chance to have my father accompany me to Promiseland, but set off finally we did, limping, you could say, my father already almost a ghost of himself, but not quite. Him—body holding pretty steady, mind faltering often—still the daddy and me still the son, he let me know. Although my father was a son too: my father’s father riding with us, Grandpa’s presence materializing more and more the closer we got to where our trip would take us. To Jordan, it turns out. This was not the destination my father nor I had anticipated, but we would find Jordan—another Jordan besides the boy who would be born in Pittsburgh while we were in South Carolina, and not the hoop star Jordan either. A third Jordan who’d been around long before MJ was born, long before basketball was born.

A Jordan we would find present in Promiseland. Someone my father and I were unaware of when we departed Pittsburgh. A surprise like the news we would hear when we returned to Pittsburgh and learned that my niece had delivered a son and had named him four or five days before she heard our news that the most ancient ancestor we had unearthed in South Carolina, my great-grandfather’s father, was Jordan, an enslaved man. His name, age (twelve years), and price noted on the original bill of sale dated 1841, deposited in an Abbeville archive.

And that could be the story. Jordan’s story could end there. An odd, entertaining coincidence. A glimpse at how the eternal, celestial spheres play games more magical than even the legerdemain that MJ exhibited on the court.

Omar says, C’mon, little man. You the one wanted to go here so bad. C’mon. Keep up, knucklebrain. Jordan looks beyond ole mighty mouth Omar who got something to say ’bout everybody, everything. Looks past Om and the string of family kids, siblings, cousins various sizes, but none shorter, none darker than he is, looks ahead to where their tall, tall Uncle Jordan in the lead hustles them on to the next ride, next exhibit hall, next sweet treat Uncle has in mind, touring the whole huge Disney World park when all he wants, Uncle Jordan please, please, is lemme go back please and get at the end of the line again and go again on one those tall, fast-turning, scary wheels, Uncle, no need to hurry, to hurry up hurry up and see all the rest, happy if we go no further than that single great ride one more time, Uncle, it fly you, squeeze you, scary enough make you ’bout to pee, don’t it. Jordan doesn’t bother to shout out what he’s thinking. Best not. Who would hear, care? All the Disney World noise and musics and bells and whistles and screams, how anybody ’sposed to hear what you were saying let alone hear what you were thinking all that long way away his voice would have to run to catch up with his Uncle Jordan strolling quick, far up ahead, all the kids trailing him in Disney World. Probably it’s me just dreaming anyway and who in the whole wide world hears you when you asleep? Don’t make no sense, do it, anyway, he thinks. None of this. He ain’t in no Disney World anyhow, him wanting to go there so bad and now a dark, real dark uncle, dark as his real father got all the kids in tow. Too much. Couldn’t be true. G’wan, turn over and go back to sleep, boy.

The day my niece and I took two cars and carted Jordan along with a bunch of family kids, and a few who are not, for soft ice cream at the Dairy Queen off the Boulevard of the Allies in Pittsburgh, it breaks my heart when I realize he is scared to say what flavor he wants. Tongue-tied, Jordan just stares and stares at the costumed colored girl serving behind a counter almost tall as him. Stares and stares up at her as if dumbstruck or spellbound or maybe instantly in love, engaging in a silent exchange with the pretty server, back and forth a couple few times before he freezes and his gaze drops a final time, deeper than shy, deeper than she can follow, and I realize Jordan can’t summon a word—chocolate or raspberry or blueberry ripple or pistachio—not because he hasn’t memorized every flavor or because he can’t read them perfectly well from posters on the wall, or even that he doesn’t know exactly which flavor he desires, but because he doesn’t want to risk people laughing if he calls out the wrong one.

Back to the dead. With my father I discover that they, the dead, are all the family we have left in the little ghost village of vanished shacks or whatever it is exactly that some locals still call Promiseland. Gone except for maybe a couple hundred folks spread out here and there on land once belonging to the old Marshall Plantation, land surrounding a school erected in the empty space where Promiseland used to be. That’s what everybody told us. By luck we were able to visit a school on the very day set aside by the local people of color each year to gather and picnic and celebrate and commemorate the ancestors who had founded this place. A school, an abandoned gas station, a few collapsing shanties, a shed that formerly housed a grocery store, perched on a few acres of bare ground memorializing the site of Promiseland.

Two thousand seven hundred and forty-two acres of Marshall Plantation purchased in 1869 by the South Carolina Land Commission may have been intended originally for the benefit of colored people who had been enslaved. However, the state legislature’s mixed motives, corruption, the shameless and systematic collusion between politicians and old-regime landowners diverted state funds appropriated for settling the newly freed. The Commission’s project gutted rapidly. Land to help the needy plundered by the greedy.

Land the Commission was authorized to buy and redistribute could have been conceived not as a gift but as righteous payback, as proper compensation or reparation, but instead the Commission offered freedmen small plots of land for sale. Though full of aspiring folks hungry for a chance to own land, to farm and start new, independent lives, the defeated Confederacy did not contain many colored consumers with ready cash or credit. A war-torn, bleeding South contained instead legions of destitute colored people. Homeless, penniless women, men, and children roaming the countryside or adrift in war-ravaged cities. People whose unpaid labor just yesterday had sustained the South’s economy, people whose subservient condition in the previously dominant social structure had reinforced the idea that whites belonged to a superior race. In such a context the notion of creating communities like Promiseland has always been chimerical. Especially since, in its heart of hearts, the wounded American South did not desire a prosperous, free colored population. Rather, the South was desperate to restore absolute control over its former property, recapture their labor, rebuild a slave economy, reduce colored people once more to a subhuman status that would reassure whites that their whiteness signified superiority and thus entitled them to command, buy and sell, transport, whip, fuck coloreds as they pleased.

Except for a few colored families both extremely lucky and extraordinarily endowed with fortitude, courage, wisdom, and stubbornness that enabled them to buy a plot of land and retain it even until the present moment, Promiseland was a species of wishful thinking. A rumor like the gift of forty acres and a mule promised but never handed over for even a temporary, trifling while to those whose labor in the fields and forests had created a Cotton Kingdom. No, unh-uh, that promised land, those rumored mules never belonged even an instant to the newly, officially, free at last, free at last, free people the US government had chosen to designate as slaves.

So in the once-thriving colored community of Promiseland, my father and I discovered only dead family to greet us. Host us. And magically they did just that. Did not disappoint. Their names and stories were spoken and welcomed us in the tiny gym of the building where a lucky few had attended school when they were allowed. Though of course my father and I also shared a sadness beyond words with all those dead who once upon a time had conceived us and sent us north, south, east, west to make lives for ourselves they would never see, lives as mysterious to them as their ghosts would be to us.

Do you remember the story of the Boy in the Bubble? I do. Quite well. Big news back in the early seventies when I was in my early thirties. People fascinated by a newborn who had to live every moment of his life confined in plexiglass. A boy who would die unless ingenious doctors and machines kept him separate from the air normal human beings breathe and walk around in. A kind of sci-fi story. Evoked wonder, awe. A sadness too. His extreme isolation pitiful. A horror story. Boy touchable only with rubber gloves fitted into his capsule.

The harder they tried to describe the world outside his plastic cage and tried to explain why he could not survive there, the more the boy wanted to go there, I bet. I’m only guessing, of course. Guessing about what he thought or felt. Can’t ask him. Or see him. Wonder if the bubble he inhabited still exists in a museum somewhere. Emptied of him. As now he’s free of it.

The boy’s situation was an obvious, painfully appropriate metaphor for the bubble of color and race I was born into and had never escaped. His story reminded me to feel sorry for myself. My self-pity, my identification with him might have afflicted me much more drastically if I had not had the father and mother I did, if I hadn’t already accumulated thirty-some years of life before I learned about the boy’s plight. Grown-up enough to accept the fact that all stories (including my own) were species, more or less, of sci-fi. Fairy tales laced with devils, angels, monsters, magic. Each of us time-traveling blind as we negotiate a vast darkness.

Eventually, NASA engineers constructed a miniature spacesuit so the boy could venture outside the bubble. But since this opportunity frightened him and encumbered his freedom of movement without truly releasing him, he tried the clumsy gear only a few times. Death almost certainly the outcome if the boy attempted life with no bubble or suit, the experts predicted, but the experts could devise no other options. As year after year passed, the boy’s unhappiness and restlessness increased, his dissatisfaction and misery deepened, and so despite being aware of the probably fatal consequences of their choice, the boy’s parents finally acceded to his wishes and demands. Gave him a chance for a life shared with other people, an uncaged life beyond the artificial skin sealing others out, sealing him in. He lasted just hours outside his tent.

Jordan knew better, knew that despite his not-great size, he was too big a boy to cry. But cry he did for Om, his large, rough, strong, funny cousin he always had wanted to be. Omar not twenty and shot down. Ambushed in the stairwell, probably hollering, here I come, here I come, you all—on the way up to pay a visit to his lady and their baby too new to have a name (or had a name that Jordan had not heard yet, probably more likely). Name Jordan would not have forgotten if he had heard it once. Iron-head Jordan never forgets, his mom told everybody. Her iron-head baby Jordan, too sweet for this world, for his own sweet sake sometimes, he had peeped her whispering once to her sister, his auntie. Auntie sweet herself, like his mom could be sweet when she chose to be, and Auntie nice, very nice with him, to him, so if anybody besides his mom knew he snuck off and cried out loud for his dead cousin Omar gunned down by a gangbanger cause Om, they say, kicked the guy’s ass one night outside a club in a fair fight, if there was one person, only one person Jordan wouldn’t mind, after all, catching him doing something he understood he was too big a boy to do, it would be Auntie.

I don’t remember Jordan at the family party when I danced with my niece, his mom. He had to work I think, but maybe he was there, invisible in different rooms. More a matter of me simply missing him, because J was quiet, shy as he usually tended to be, except one-on-one, and then he just might wake you up with a thought you’d never thought of or hardly expected anyway till you caught on and remembered oh yeah it was J talking and if he didn’t usually have all that much to say, still it was J, and you never know what’s coming out that boy’s mouth. Anyway, I danced with his mother that evening and aside from how slim, how graceful and how hip she glided and spun, how fine her moves caused me to feel, I also felt like we had been dancing a long time before, warming up, getting ready long before our glances met and I walked across the room toward her and she rose up smiling off the sofa, and offered her hand, preparations in advance seamlessly in place so we got smoothly into the middle of it long before we started to dance together, and how grateful to her I felt. And I also recall kinda checking out the room, and now I’m sure it was to spy if Jordan was in it, or coming or going or watching from a doorway, a corner, a shadow, watching the dance.

I come in here to say I’m sorry, baby, truly, truly sorry I smacked you, Jordan, his mother whispers, and then says, but I got to tell you, baby, Imma hit you again, baby, harder next time if you ever call your brothers and sister, half-brothers and half-sister again, boy. Where did you get that word, Jordan? Your sister and brothers not half nothing. No half-brothers, half-sister in this house. You are all my beloved children, brothers and sister, my beautiful children, brothers and sister living in this house together and I love each one of you very much and will long as my feet walking God’s green Earth and longer, baby. Any man come round here to visit me or stay with us must love all you all, too, father or not, love each one of your brothers and your sister and they better and they will, or won’t be stepping through our door ever again.

In South Carolina my father lost it. Badly, embarrassingly, more than once. Talking out loud, quite loudly to himself in public, not the worst moments. I understood that conversations with himself were a necessity, especially in South Carolina where for four hundred years nobody, except maybe family or those we embraced or embraced us as a kind of extended family, had chosen to listen to a single word he said. I understood, no problem, that eerie sometimes whine and sometimes stern, peremptory TV announcer or preacher voice that issued suddenly from him, telling everybody what they needed to hear, what to do, where to go, what belonged to him that they had stolen from him, what he’d returned to South Carolina to claim as rightfully his. Fragments and elaborate set pieces my father’s voice performed down there in the South as unselfconsciously as birds sing or birds shit, Daddy, I heard you and do now, your words, as they should, surprising, teaching, piercing me like seeing you, a large, brown, grown-up man drop down to his knees and pray each night beside a small bed. One of two—one yours, one mine—small beds in the small motel room in Greenwood, South Carolina, we shared.

Worse by far than your outbursts or cooing or pronouncements or crooning to yourself, Daddy, or you fielding looks people dared at you or stole at you or received from you, wagging their heads behind your back after you passed by. Worse than the truths you bore within yourself and I had managed over the years to avoid or neglect or speak or mirror only rarely, only when I summoned up the courage not to forget what I choose not to remember. Worse than all those speeches and posturings in South Carolina, worse than any of that by miles, the very worst was your bewilderment, your empty hands I could neither fill nor reach out and squeeze in mine. For fear of awakening you. Of frightening you. Of losing you. Awakening you in a more terrible nightmare whose raging truths harder to bear, harder even to inhabit than the one shaking you to pieces right there before my eyes, the two of us inside miscellaneous municipal buildings, museums, coffee shops, libraries, bookstores, churches, dinners here and there in somebody’s house to which we were invited and politely declined, walking the streets of little sleepy Southern towns beneath which our dead were buried but not dead.

Omar. What you think of Jordan?

That ain’t no hard question. You already know the answer. You a butthole, lil Jordy. Like you been since you born, Midnight.

Fuck, man. You know I ain’t be asking you that shit, man. You know who I’m talking ’bout. Michael Jordan. What you think of MJ. Really. Seriously, Om. C’mon.

Seriously. Serious as cancer. Boy can do it.

Is he the best ever?

No. You the best. Best little nothing of a little tagalong nothing butthole walking round here on two legs I ever seen.

Shoulda known better than to ask you, Chump-ass. Shoulda known better.

Fuck you, Omar. No, Omar. Sorry, Om. Didn’t mean it, he almost shouts out loud. Not fuck you, Om. Just wanted to know. Asked you to help, that’s all.

Jordan runs the names again in his head—sorry, Om. Poor Om shot down dead. Jordan. Poor, long-time-ago-slave-boy Jordan. Sorry. Sorry. And sorry me. Sorry me, he thinks. Sorry Jordan. Jordan. Shame on crybaby me. Sorry me. Helpless. Tears sneak, drip, roll. Burn.