During the summer of 1979, I was among a group of Americans studying Spanish at the University of Madrid. When the Fourth of July rolled around, our Spanish friends decided to throw us a big party. The holiday meant nothing to them, of course, but they were extraordinarily gracious hosts and wanted to honor our nation’s birthday as well as show us a good time. The gathering was held in the Sala de Música, a wonderful upstairs room, with chairs and a stereo, that opened onto a large balcony shaded by a reed awning. While Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run pumped from the stereo we perfected our Spanish before pitchers of sangria, brimming pots of gazpacho, and heaping platters of paella. It was all superb, but it didn’t feel like the Fourth of July. At some point, one of my American pals sidled over to me and said, “You know, I could really go for some fried chicken, tater salad, and sweet iced tea right about now.” If I hadn’t realized it before, I certainly did then: Food is about much more than taste and nourishment—it’s about culture and identity, too.

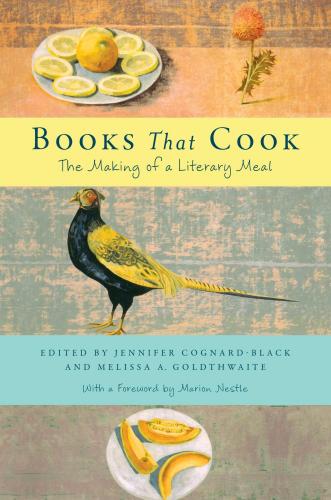

This point is nicely reinforced in a readable and entertaining new anthology, Books That Cook: The Making of a Literary Meal. Playfully edited by Jennifer Cognard-Black, professor of English at St. Mary’s College, and Melissa A. Goldthwaite, professor of English at Saint Joseph’s University, the volume is organized like a cookbook, from starters and main dishes to side dishes and desserts. The selections, some penned especially for this collection, include cookbook excerpts as well as poetry, memoirs, essays, and fiction. Many include recipes, either “in service of the story” or to demonstrate how “the story serves to contextualize the recipe.”

Notables one might expect in such a collection are here—James Beard and Julia Child, for example, plus poets and writers like Fannie Flagg, M. F. K. Fisher, Gary Snyder, Maya Angelou, and Alice B. Toklas, all of whom have written beautifully about food. There are also a few important early figures like Amelia Simmons, whose 1796 American Cookery was the first cookbook written by anyone on these shores. But the majority of the pieces are by lesser-known contemporary writers and professors scattered from coast to coast. Most of them are good, several superior, and they significantly add to the pleasure of this collection, providing the reader with a handy list of new authors to explore. Readers will also likely think of pieces that should be included but aren’t—for me, Herman Melville’s chowder chapter from Moby-Dick would have been de rigueur—but that’s part of the fun.

The editors’ skill at serving up mouth-watering selections is repeatedly demonstrated throughout the text. In the poem “Making the Perfect Fried Egg Sandwich,” photographer and educator Howard Dinin writes, “Swirl the pan / gently, / let the butter lap / the sides. / Then once it pools, / hold the cup / above the surface, / intimate as you please, / and tip the cup, / slowly please, / and slide the egg out.” Equally enticing are the instructions on how to eat an artichoke from Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle, and Simone Beck. “Pull off a leaf and hold its tip in your fingers,” they write. “Dip the bottom of the leaf in melted butter or one of the sauces suggested farther on. Then scrape off its tender flesh between your teeth.” Got a hankering to cook some trout? According to David James Duncan, a fly-fishing enthusiast as well as an essayist and novelist, it’s not rocket science. “Butter aside,” he explains, “there are no Trout Frying Commandments. Almonds, garlic, and cornmeal offer interesting counterpoint if you like fried almonds, garlic, and cornmeal; needless distraction if you don’t. The flesh under discussion requires no trick additives. If you open your heart and use enough butter, a trout fried in a dredged-up chrome fender over an acetylene torch is worth eating.”

Foods and culinary customs from several ethnic groups and every region of the United States are presented, but the Southwest and South are the most memorably conjured. In “Puffballs: Finding the Inside,” English professor Thomas Fox Averill describes a little pueblo north of Albuquerque, New Mexico, where food is inextricably braided into the townscape itself: “Homes, decorated with pine branches, wreaths and hanging ristras of red chiles, and totems offered to sun and wind. Small tents with hand-lettered signs offered tortillas and fry bread, skewers of beef, venison, and chicken.” In “Whistle Stop, Alabama,” native Alabamian Fannie Flagg shares a recipe for buttermilk biscuits. The ingredients are simple—2 cups flour, 2 teaspoons baking powder, 2 teaspoons salt, ¼ teaspoon soda, ½ cup Crisco, and 1 cup buttermilk. “Sift dry ingredients together,” Flagg instructs. “Add Crisco and blend well until like fine meal. Add buttermilk and mix. Roll out thin and cut into desired size biscuit. Bake in greased pan at 450 degrees until golden brown.” The magic happens when those golden-brown delights come out of the oven, served on a heaping platter by loving hands.

Other selections present passionate arguments for retaining authentic foodways. In “Boiled Chicken Feet and Hundred-Year-Old Eggs” Shirley Geok-Lin Lim, a writer and emeritus professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, opines that the modern “health foods” rage “seems to me to be yet another progression toward banning the reek, bloodiness, and decay of our scavenging past and installing a technologically controlled and scientifically scrutinized diet.” Growing up Chinese-Malaysian during the 1950s, fresh food was her norm. “We thought of frozen meat as rotten, all firm warm scented goodness of the freshly killed and gathered gone, and in its place the monochromatic bland mush of thawed stuff fit only for the garbage pail.”

While this volume’s organization is resonant with its subject, the individual pieces do not always comfortably fit where the editors have chosen to place them. For example, in “Starters” we are presented with an eighteenth-century description of how to procure the best meat along with recipes for roast beef and roast mutton, and instructions for how to stuff a turkey. Similarly, the turkey-bone gumbo in “Main Dishes” might initially seem better in “Starters”—that is, until we realize that the author of the piece is using one of New Orleans’s distinctive Thanksgiving culinary traditions to make a more substantive point about the centrality of the city to her sensibility and newfound identity. Because so many of these selections operate on several levels, including the metaphorical, it must be asked if the cookbook format is quite right. Editors Cognard-Black and Goldthwaite appear to have considered this, and in their introduction they encourage readers to experiment with alternative associations. They helpfully suggest that “another way to approach Books That Cook” is “in terms of major themes.” Among the categories they provide, complete with a listing of selections for each, are “Food and the Environment,” “Cultural Critique,” “Ethnic and Cultural Identity,” “Love and Desire,” and “Family Relationships.” This alternative structure would seem more logical and elegant for a purely literary anthology of food and cooking, but since the editors stress the deep connections between “literatures of food” and the “form and purpose of cookbooks,” it’s easy to understand why Cognard-Black and Goldthwaite chose as they did. From their enthusiastic flour-to-the-elbows perspective, Books That Cook is more than simply another anthology, it’s a living text to be taken into the kitchen and spattered with sauces and gravy. In short, it’s meant to cook.