This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

On a sweltering weekend in July 2022, in Kansas City, Missouri, more than two hundred doctors gathered at the Sheraton Hotel to explore an alternative health-care delivery model, called direct primary care (DPC), which promised to stem the rising tide of their professional despair. Most of the attendees were generalists—family-medicine doctors, internal-medicine doctors, emergency-medicine doctors, pediatricians—but a handful of specialists also showed up: cardiologists, dermatologists, intensive-care physicians. They came from red states and blue states, rural areas and urban areas. Some had been practicing medicine for decades; others had just finished their residency training. Some came with like-minded peers and colleagues, but many had come alone, and it was a good bet that they hadn’t advertised their pilgrimage to their colleagues back home.

They carried tattered briefcases and well-worn laptops, which they cracked open at various times throughout the conference to tackle a new batch of patient messages, or finish up clinic notes from the week before. High-stakes multitasking wasn’t a problem for this crowd. They were used to answering pages, filling out forms, handling infinite parallel tasks; watching people die and moving swiftly on to the next assignment; sitting in their cars for a few extra beats after pulling up at home, straining to transition from doctor to parent, or doctor to spouse.

The attendees slid colored ribbons inside their lanyards: green for just looking, pink for just launched, blue for ready to mentor, and black for about to quit.

The black one caught my eye. Just a few months prior, I had quit my job as a hospital-medicine doctor at the Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. After three years of residency and four years in practice, I could no longer endure the twelve-hour days, the suffocating amount of data entry, the grating sound of the pager, and, most upsetting, the nagging internal voice telling me to move on to the next patient, move on or you’ll never get out of here—even when my conscience was telling me to slow down. Many nights, I came home with a headache, unable to do much but melt cheese over nachos, park on the couch, and fall asleep in the nook of my husband’s arm. Recently we had gotten pregnant, and my first-trimester nausea had made this routine even more difficult. In many ways, it was the perfect time to step back.

As I debated my future as an internist—knowing, from my own experience and the several years I’d spent running a storytelling program for doctors, that physician burnout was a national epidemic—I began to search for doctors who had found ways to reclaim their profession, rather than just publishing op-eds and academic papers.

Earlier that spring, a peer had connected me with Vance Lassey, a family-medicine doctor in Kansas and president of the DPC Alliance. It was Lassey who had encouraged me to come to the DPC summit to learn more about their movement. “It’s the only conference where the attendees are smiling, not milling around like zombies in the land of the dead,” he’d written in an email. “Maybe you’ll find ‘your people’ there. I know I did.”

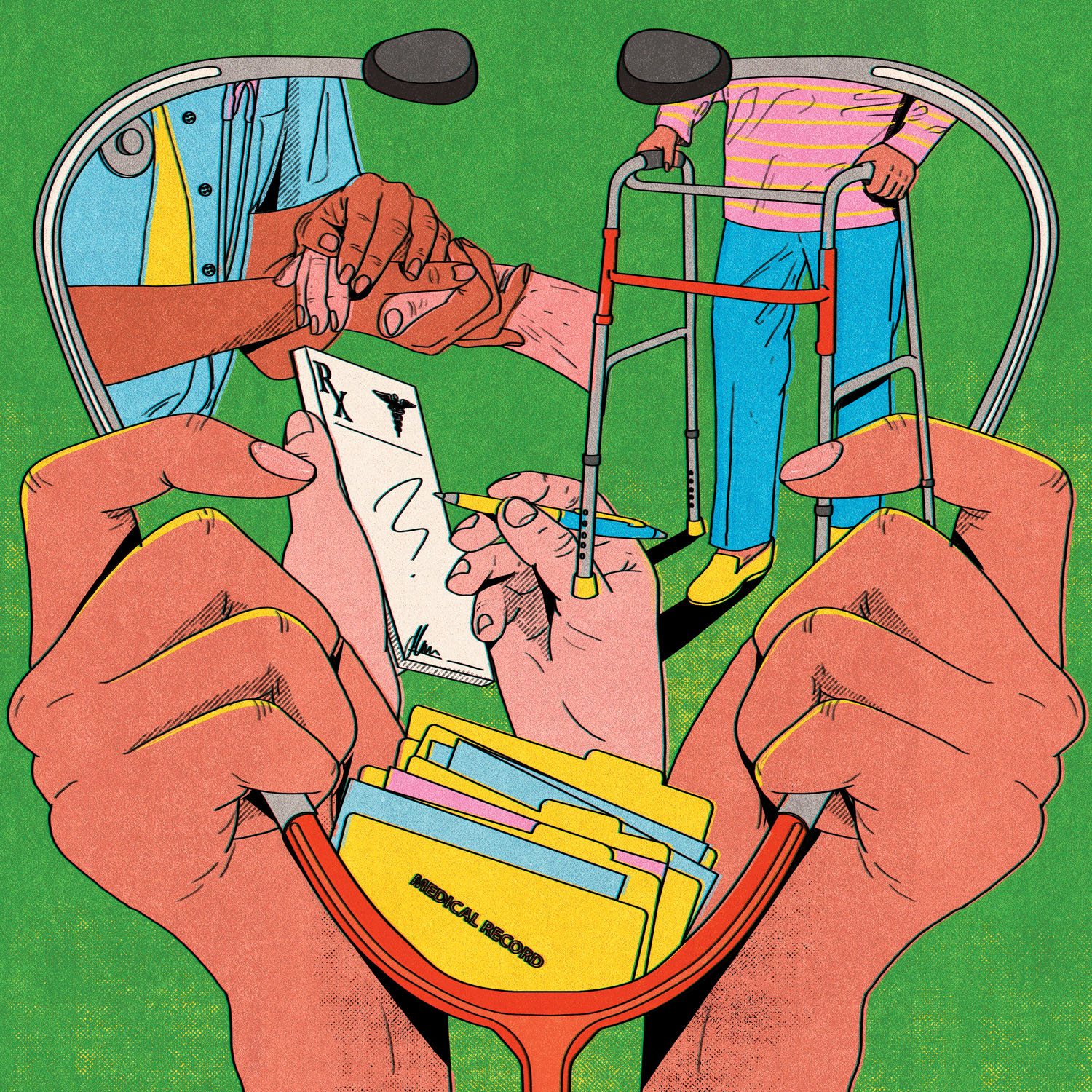

Simply by being at this conference, I felt a little rebellious, like I’d joined a ragtag group of revolutionaries. What I didn’t expect was to meet so many others who shared their disillusionment with the medical system so openly. Instead of chatting about the hottest new research or latest trends in medical education, breakfast-table conversations cut to the quick. There was the rural-medicine doctor who was so overwhelmed at work that she fantasized about getting injured just so she could rest. There was the geriatrician who one day realized that her patients could barely shuffle to the exam room with their walkers before their allotted appointment time was up. There was the pulmonologist who quit his job in the ICU when he realized that the medical system pours resources into patients after they get critically ill, but does little to prevent disease from occurring in the first place. And there was the doctor who practiced on a military base in Guam, who realized while watching a spectacular sunset that his assembly-line practice was making him depressed.

What a relief it was to hear these stories. Usually medical conferences focus on clinical topics: Updates on Thrombosis and Anticoagulation, Glycemic Control in the Inpatient Setting, Evidence for Steroids in COVID-19. Occasionally, a lecture on physician burnout made it onto the schedule, but even then, it was usually in some forgotten back room, delivered by an institutionally appointed Chief Wellness Officer to a smattering of sad, mostly female physicians. The tacit message was: Burnout is highly inconvenient, and should be addressed as quickly as possible in order to get back to the business of clot busting and sugar taming. Examining the container of our profession, and the issues driving the mass exodus from it, was off-limits.

But on this Saturday morning, in the Grand Ballroom, Lassey walked onto the stage to do just that. Broad-shouldered and bald with a reddish beard, he projected a warm, leonine presence. “This feels like home,” he said, then clicked to his opening slide, which listed his credentials as “Owner, CEO, Builder, Part-Time Janitor, Family Physician, and Overall Nice Guy.” Then the lights dimmed.

“I’ve always wanted to be a doctor,” he said, flanked by a photo of himself as a boy, pressing a yellow toy stethoscope to his mother’s chest. “But forty years later, I was here.” He showed a series of photos of himself at a hospital nurses’ station, filling out stacks of paperwork that shot up like stalagmites until he finally lay his head on the counter from exhaustion.

“They call this physician burnout,” he said, pacing in front of the screen as it filled with images of doctors with their heads in their hands or leaning on a crash cart or sliding down against a wall. “But burnout is the wrong term. The right term is moral injury,” he continued, citing a paper by psychiatrist Wendy Dean and surgeon Simon Talbot, which emphasized that it wasn’t the doctors who were broken, but the system. “I like to summarize it as a conscience violation,” Lassey said. “We simultaneously know what someone needs, but are unable to provide it due to constraints beyond our control.”

Medicine used to be simple, Lassey explained. Doctors were embedded in their communities. They knew and were known by their patients, who paid them for their services directly. “But then it went from a relationship between two people to a relationship between three people. And I think we can all agree, when you’re in a committed relationship, and a third person enters that relationship, things get weird.”

What we have now, Lassey said, is money flying over the doctor’s head and into the pockets of payors—namely, insurance companies and government. “Don’t get me wrong,” he clarified. “We all like insurance. We have car insurance. Doesn’t cost us much money, and if we crash our car, they’ll buy us a new one. But we don’t use insurance for every oil change or new set of tires. If we did, the insurance would cost more than the car.”

Which is precisely what happened with health care, he argued. We pay for insurance to cover everything from a throat swab to open-heart surgery, and then insurance companies get to decide if, when, and how doctors get reimbursed. Worse, on the way down, the money filters through an infinitely complex web of administrators and stakeholders.

This results in doctors spending hours filling out prior authorizations and ticking off boxes in the electronic health record to justify reimbursement, rather than focusing on the patient in front of them. Meanwhile, patients in America face the highest health-care costs in the world: $3,000 for a single stitch in the emergency room or, in some more Kafkaesque examples, $11 to cry during a clinic visit (billed as “Brief Emotional Assessment”) or $40 to hold one’s own baby (billed as “Skin to Skin After C-Sec”).

Direct primary care marks a path back to economic simplicity. It works like this, Lassey explained: “The patient gives money to the doctor. You exchange money for goods and services.” Sure, he added, patients can use insurance for expensive interventions, such as cancer treatment or brain surgery. But for primary care, they pay out of pocket—usually a monthly fee, whether they’re healthy or sick, like a cell-phone bill or gym membership. In this model, everybody wins: Doctors get their agency and sanity back, and patients get unlimited access to their doctor, whose job it is to keep them healthy and out of the hospital. “We’ve done a therapeutic middlemanectomy,” Lassey joked.

I looked across the table at my physician colleague, Michelle, who had become interested in the direct primary care approach after working just a few years at an academic hospital. We’d met in San Francisco the year before and immediately bonded over our shared love for the arts: I was growing my storytelling program for doctors, and she had written a poetry collection about how the ICD-10 codes in the electronic chart dehumanized patients. We were, admittedly, getting a bit swept away. Already this conference was radically different from the dozens we’d attended as young physicians over the years. Here there were no condescending platitudes about how medicine is a calling, just a stunning transparency about how damaged American medicine had become, and a concrete idea about how to move forward.

In today’s popular imagination, doctors are often associated with power, prestige, and wealth. The white coat is a coveted status symbol; parents pressure their children into the profession, understandably so—a recent article in the Washington Post cited the average American doctor’s salary of $350,000 a year. But medicine wasn’t always an elite profession. In the nineteenth century, doctors consisted mostly of barber-surgeons, overworked midwives, and people peddling dubious elixirs who occupied a much different class than lawyers and diplomats. Doctors’ status began to change when germ theory came to light in the early twentieth century. Science progressed, medical schools grew more rigorous and standardized, and by the middle of the century, the profession had entered a “golden age,” enjoying high wages and public esteem.

In the last few decades, however, the landscape of physician labor has shifted dramatically once again. In the 1980s, more than 70 percent of doctors were self-employed, working autonomously in private practice. In recent years, corporate giants such as CVS, Walmart, and Amazon have aggressively bought up primary-care practices, and private equity firms have invested in and restructured numerous hospitals, clinics, and surgical centers with the goal of reselling them to even larger firms at a profit. The result is that more than 70 percent of doctors are now employed by hospital systems or similar corporate entities, with dramatically diminished control over their day-to-day practice. Despite their high salaries—or perhaps because of them—doctors are pressured to generate revenue, which in turn has warped the fundamental purpose and service they are supposed to provide.

To practice well, primary-care doctors need time to get to know their patients’ values and life stories. While a focus on health and prevention is vital, primary-care doctors also have the difficult intellectual task of encountering undifferentiated symptoms, sifting through possible diagnoses, and guiding treatment in what is often a stepwise manner, mired in uncertainty. This relationship, grounded in trust and continuous engagement, is arguably at the heart of clinical medicine.

But between shorter visits, larger panels, and an emphasis on producing “relative value units” rather than excellent care, many physicians I spoke to feel less like agents of power and more like an exploited class operating in survival mode. Primary-care doctors are especially vulnerable to these forces. As of 2017, their average annual salary was less than two-thirds that of specialists, whose productivity is more easily measured through discrete encounters like procedures and surgeries. This income gap is even starker for primary-care doctors who care for patients on Medicare and Medicaid. Administrative tasks, meanwhile, are supplanting valuable time spent with patients face-to-face: A 2023 survey conducted by the American Medical Association of more than a thousand physicians showed that doctors spent an average of fourteen hours per week completing prior authorizations.

Without time to think, primary-care doctors often succumb to over-testing and over-referring, to minimize risk and stay afloat. Some in the industry feel that doctors in primary care are no longer operating at the top of their licenses, and have called for a new era of nurse practitioner– and physician assistant–driven primary care, which is cheaper to administer but whose quality may not be comparable given potentially dramatic differences in training. This trend might explain why medical students, who graduate with an average debt of $203,000, are steering away from specialties like family medicine, emergency medicine, and pediatrics toward more lucrative and lifestyle-friendly specialties like dermatology, radiology, and physical medicine and rehabilitation.

Interestingly, the specialists aren’t exactly happy either. Forty-nine percent of dermatologists and 54 percent of radiologists admitted they were “burned out” in a 2023 survey. And the overall outlook for doctors is dismal: Twenty-four percent of physicians report being clinically depressed; one in fifteen has contemplated suicide in the last twelve months, while one in five wants to quit or retire in the next two years. Perhaps most illuminating, 70 percent would not recommend a career in medicine to others. In short, medicine is facing an existential crisis.

Framing the degradation of the medical profession as simply a matter of corporate takeover is tempting, but it isn’t entirely accurate. Physicians could have organized or resisted these changes, but most haven’t, arguably for three reasons—complacency, ignorance, and passiveness.

Complacency, because so many health-care professionals have had some incentive to embrace the fee-for-service method. With loans to pay off and families to support, this has been a reliable path to financial stability, if not some freedom.

Ignorance, because health-care economics is not a physician’s focus. Except for some polymaths and policy wonks, doctors spend much of their formal education reading about infectious microbes and cytokine gradients—not the ins and outs of Medicare reimbursements or the profit models of pharmacy-benefit managers. Some, especially those with more complicated paychecks, may not even understand where, exactly, their paycheck comes from, which leaves them powerless to weigh in on the pragmatics of health-care delivery.

And passiveness because most physicians have come of age in a professional environment of abuse and hazing, where working while sick or sleep-deprived has been disturbingly normalized. Practicing medicine is a privilege and sacrifice, the narrative goes, and prioritizing one’s own needs is unbecoming and selfish. In some ways, physicians are the perfect target for corporate exploitation: Submission and silence is embedded in our culture.

What can be done about it? The American Medical Association, traditionally a powerful lobbying organization, counts only 17 percent of American physicians as members, compared to 75 percent in the 1950s. While the organization is working to reduce administrative burdens for doctors, many doctors I spoke to feel that it has generally prioritized relationships with corporate medicine over improving working conditions. One doctor, who asked not to be named, pointed out that of the $493 million in revenue that the American Medical Association generated in 2022, only $34 million came from membership dues, whereas $293 came from royalties and credentialing products, such as the Current Procedure Terminology coding system and the compiling and selling of physicians’ prescribing data. She added, “I do think there’s very good people in the AMA—there’s people who want to reform it from within. But overall it’s been kind of a sore spot for physicians.”

Unionizing is another way for doctors to advocate for reform—and indeed, resident physicians, who regularly work eighty-hour weeks and twenty-eight-hour shifts for an average salary of $64,200, have had notable success doing so. In the last two years alone, residents have unionized at Stanford, the University of Vermont, Montefiore Medical Center, George Washington University, Penn Medicine, Mass General Brigham, and other institutions—a stunning sea change of physician-trainee activism. But attending physicians have yet to follow suit: As of 2021, less than 6 percent of practicing physicians and surgeons were union members.

Even if attendings did unionize, the change would likely be slow and incremental. Forming a union essentially amounts to shifting a small bit of power away from health executives and back to doctors so that they can bargain for salary, benefits, decreased caseloads, and increased support. But in the end, those physicians will still be working inside a knotted fee-for-service system plagued by distorted incentives and relentless churn. This is why the DPC solution is so compelling to so many: It’s a radical change that can happen immediately. All one has to do is jump.

In the fundamental reversal that direct primary care envisions, a well-trained primary-care doctor should be able to handle up to 90 percent of medical care and have access to a trusted network of specialists which they can lean on through in-person visits or virtual-referral platforms such as RubiconMD.

At the heart of this reversal is an economic model designed for incentivizing health. DPC doctors charge a monthly fee that ranges from $50 to $150 (median $80), depending on factors such as geography, a patient’s age, and discounts for family plans. This price structure enables doctors to carry a caseload of between four hundred and six hundred patients, compared to 1,500 to two thousand patients in the insurance-based model. On a more granular level, this means seeing an average of six to ten patients per day, as opposed to fifteen to twenty.

This subscriber model allows doctors to provide unlimited in-person and virtual visits to their patients. Depending on the doctor, the fee might include in-office procedures, such as EKGs, spirometry, joint injections, skin biopsies, cryotherapy, ear lavages, even such minor surgical procedures as vasectomies or hemorrhoidectomies. For labs and imaging, DPC doctors negotiate cash prices with local vendors. For example, they might call up Quest or LabCorps and negotiate a cash rate of four to five dollars for a comprehensive metabolic panel, rather than $150 to $250 when billed through insurance. Or they’ll call up a local imaging center and negotiate a cash rate of $330 for a lumbar spine MRI with a radiologist’s read, compared to $3,750 when billed through insurance.

For medications, generics are highly affordable if purchased from distributors wholesale—even more so than if purchased with a coupon from a service like GoodRx. According to Ryan Neuhofel, who gave a lecture at the DPC summit called “Pharmacy 101,” lisinopril costs $0.78 for a month’s supply wholesale (rather than $15 if billed through insurance); rosuvastatin costs $1.20 per month (compared to $190 through insurance); citalopram, $0.78 (instead of $20); plavix, $1.60 (versus $110). “It just doesn’t make sense anymore for a two-cent lisinopril to go through insurance,” says Kenneth Qiu, a DPC doctor in Virginia who started his practice right out of residency. “The things that don’t need to be insured, we’ve literally pulled out of insurance.”

Depending on state laws, some DPC doctors even have the option of dispensing medications on site, which offers more touch points with patients, and the opportunity for more clarity about pharmacology and drug costs. Usually, doctors who dispense keep fifty to 150 of their most prescribed medications in stock, including supplies like nebulizers, instead of the five hundred to 1,500 medications kept in stock by retail pharmacies. Lassey’s clinic in Holton, Kansas, for example, has a back room specifically dedicated to storing and organizing meds, with a refrigerator, pill counter, pill bottles, or “drams,” and a label maker. (“Label makers suck,” Neuhofel said. “It’s the biggest complaint I hear about dispensing meds.”)

Some doctors, such as Jillian Scherer, a family-medicine doctor in rural Illinois, even do “drug drops.” Scherer provides primary care to employees at several small businesses in her area. Every one hundred days, she leaves work at two in the afternoon and pedals to town in a Velomobile to deliver medication in little bags emblazoned with each patient’s initials, like a mother delivering lunch to her children. “I promise, it’s legal!” she said.

Neuhofel, who practices in Kansas, set up five lockboxes outside his clinic so that patients could pick up their meds after hours with a temporary code. (State law allows doctors to dispense medication to their patients as long as they don’t do so to the general public.)

What about expensive interventions like chemotherapy, immunotherapy, surgery, or hospitalizations?

“Then we start entering the insurable space,” said Qiu. “I don’t think you’re going to meet a single DPC doc who doesn’t recommend their patient have insurance.” Patients are encouraged to buy low-cost insurance products, like low premium, high deductible plans, health savings accounts, health-sharing organizations, indemnity plans, or catastrophic insurance, all of which are put in place to cover, as one doctor put it, “the worst year of your life.” The so-called platinum plans with sky-high premiums, they argue, offer terrible value because they require customers to sacrifice a huge portion of their income for the worst year of their life every single year.

To get a better sense of the patient experience in direct primary care, I asked Molly Breitenbach, a longtime patient at a Kansas DPC, to walk me through a typical appointment, starting in the waiting room.

“There is no waiting room,” she said. “You go in and the nurse immediately takes you back.”

Breitenbach switched over to DPC following an agonizing communication lapse with her doctor during a miscarriage. “I’d had a beta drawn,” she told me, “and they hadn’t given me the results yet. Meanwhile, my pregnancy-test line was getting fainter and fainter. I knew something was up, but I couldn’t get ahold of anyone,” she said. She left the practice two months later.

Now, she says, she has easy access to her doctor, and spends plenty of time with him during appointments. As an example, she told me about a recent visit during which they dove deep into her family’s history of high cholesterol. They decided to order a blood test called LP(a), which came back extremely elevated. “Sometimes I wonder if we ever would have caught this had I not been with a physician who had the time and the mindset to do this research,” she said.

Pat Fontaine, a sixty-five-year-old retired Marine Corps officer, was Vance Lassey’s patient in the traditional system after years of bouncing from doctor to doctor in the military and hiding the truth about his physical condition for fear of losing his career. He credits Lassey for getting him to open up about his health, so much so that when Lassey transitioned to DPC, Fontaine trimmed back his insurance coverage in order to keep him as his primary doctor.

“Appointments are blocked for an hour, compared to five or ten minutes in the old model,” Fontaine said. “And in that time, we’re going to lift the hood and talk about everything related to the issue. In the middle of this, he can stop to do research, get online, or send a query to a subject-matter expert. So when you leave, there’s no doubt as to what’s going on.”

Four years ago, Fontaine was on track to develop type 2 diabetes. “In the old system, it would have been: Okay, here’s your metformin, here’s your insulin, try not to poke yourself too badly, and away you go,” he said.

Fontaine and Lassey spoke at length about his condition, which ran in Fontaine’s family. “My understanding is, insulin forces blood sugar out of your bloodstream,” Fontaine told me. “But it’s got to go somewhere. Well, it goes into your liver, and that spills over, and now you’ve got body fat going through the roof. You really can’t put ten pounds in a five-pound bag if you just push hard enough. That’s what, in my opinion, insulin does.” Fontaine and Lassey spoke about making radical changes to his diet, and more importantly, to his overall conception of what it means to be healthy and well. Three years later, Fontaine says he’s more than eighty pounds lighter and physically stronger with a normal blood-sugar level. In addition to coming off metformin, he was able to come off four (“count ’em—FOUR,” Lassey wrote to me in an email) blood-pressure medications.

“In the old model, I’d probably be a couple years into insulin,” Fontaine said. “But I’m healthy now. I cannot imagine ever going back to the old way. It’s been what medicine is supposed to be like.”

People often conflate the DPC model, designed to drive down costs, with “concierge medicine,” where patients pay tens of thousands of dollars per year for quality time with their doctor. Indeed, the DPC movement was initially inspired by concierge medicine, after a Seattle primary-care physician named Garrison Bliss noticed how doctors at a boutique practice called MD2 had successfully deployed a membership model for wealthy patients. Bliss, who never shied away from difficult problems—he is the son of a reproductive-rights activist, and a descendant of famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison—began brainstorming ways to democratize the model, convinced that it had transformative potential, rather than being just a luxury service.

In 1997, Bliss opened a membership-based practice for everyday clientele. A decade later, he teamed up with his physician-cousin, Erika Bliss, to open Qliance, an investor-backed company designed to bring DPC to scale. Their first step was to lobby the Washington state legislature to define and legalize DPC as a novel entity, separate from health insurance, so that they wouldn’t be shut down by the insurance commissioner for selling insurance without a license.

Their practice grew quickly to include seven clinics, high-profile clients like Expedia and Comcast, and a business deal with Centene, a managed-care organization that linked Qliance to Medicaid and helped quadruple their caseload from 10,000 to 40,000 in just months. Operating in a capitated model, Centene and Qliance planned to split the money not spent on unnecessary care—what’s called a “gain-share agreement”—but when the extent of the savings came to light, the deal collapsed. “We were getting too successful,” Erika Bliss told me. “If they save too much money, Medicaid comes back and says, ‘Great job, now we’re going to lower your premiums.’ They’re trying to keep their expenses in a narrow band.” As a result, Qliance went bankrupt.

By then, the Blisses had inspired a new generation of doctors to continue experimenting with the DPC model, including many who serve low-income patient populations. “When I left the system,” one doctor at the DPC summit said to me, “I was surprised by how many of my high-income patients stayed behind, and how many of my low-income patients came with me. I think it’s because they saw the value in the model.” Another told a story about excising a cancerous skin lesion from the back of a farmer who, in the traditional model, would have had to commute hours to the nearest dermatologist and risk getting slapped with an unexpected bill; another talked about designing his practice specifically to serve lower-income patients who have HIV and hepatitis C.

Perhaps the most striking example of DPC for the underserved I encountered was Antioch Med, a full-spectrum family-medicine clinic in Wichita, Kansas, cofounded by physicians Brandon Alleman and Nick Tomsen. Over burgers at a restaurant in Wichita, Tomsen explained to me how, during residency, his ambition to provide cradle-to-grave care at a local federally qualified health center hit a wall when administrators insisted on excluding obstetrics because they couldn’t figure out how to bill for it without losing money. This was a dealbreaker for Tomsen, who wanted delivering babies to be a core aspect of his practice.

So instead, Tomsen teamed up with Alleman, a friend from medical school, to open a DPC clinic in a neighborhood he described as a “health desert.”

“We opened our doors in July 2016 and thought maybe we’d grow by fifteen to twenty patients a month,” Tomsen said. “But in the first month, we had forty-seven. Six months in, we had around three hundred. It was crazy.”

Somehow, the doctors managed to gain admitting privileges at a local hospital, Ascension Via Christi, where they now practice obstetrics under the DPC model. Antioch’s foray into obstetrics reflects a wider trend in the DPC community, of finding innovative ways to bring specialty care into the DPC ecosystem. Many of the doctors at the summit had a carefully curated Rolodex of specialists they could call who were willing to accept cash.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of this is the Surgery Center of Oklahoma, where patients can view the price of any operation on a drop-down menu on the center’s website. Laparoscopic appendectomy (including anesthesia and uncomplicated postoperative care): $7,368; bilateral mastectomy: $13,085. As I clicked through the site, I felt disconcerted by how nakedly transactional it all seemed. Then again, the price transparency was liberating. Patients are consumers with a lot at stake, and so long as medicine is a business, price obscurity, and the anxiety that comes with it, will be profitable for big health systems and insurance companies.

After the DPC summit, Michelle and I drove north into Kansas, our rental car undulating gently through a landscape of bucolic farms. We were headed toward Vance Lassey’s clinic, a 3,000-square-foot structure he’d famously helped construct with his own two hands. “There’s only one traffic light in town,” Lassey had told us. “Turn left at the light, and then right at the cell-phone tower.”

Along the way, Michelle and I tried on our best arguments against the DPC model. Could it truly integrate with the rest of the health-care system? How would we track the quality of care? What about other solutions, like Medicare for All? Were it and DPC mutually exclusive? (“No,” Erika Bliss said. “Medicare could say, we will pay providers on a bunch of different models, and one of them could be a monthly fee model.”)

Would large health-care corporations lobby the DPC model out of existence? What about encroachment or brand dilution from companies that DPC doctors refer to as “DINOs”—or “DPC in Name Only”—such as One Medical, which uses a membership model but continues to bill insurance? (Just weeks after the 2022 DPC summit, Amazon announced it would acquire One Medical for $3.9 billion, news which was met with a shrug by Qiu. “So far it hasn’t really made any meaningful difference,” he wrote to me. “Big players move slow.”)

One common accusation against DPC doctors is “patient abandonment.” The argument is that by reducing their patient loads, DPC doctors are worsening the overall primary-care shortage in the health-care system. Lassey emphatically resists that argument. “Would you rather take care of six hundred people exceedingly well, three thousand people really crappily, or zero people because you burned out and quit? I think we can all agree that we need more physicians, more residency programs. But we have no moral obligation to suffer,” he said.

Then there’s the responsibility of owning a small business. Doctors switching to DPC often must pare back their expenses; take out a loan or a home-equity line of credit; rent an office, buy medical equipment, recruit patients, hire staff. And once the business is up and running, there’s all sorts of things to keep track of, from managing memberships to stocking meds to washing the bathroom floor.

At the DPC summit, little stories of failure and triumph abounded—like the doctor who sold her house and moved to a new state to get her practice started, or the one who did her first patient’s pap smear on the floor of her twelve-by-twelve clinic room because her exam table was on backorder, or the one whose patient, a retired lawyer, took out a billboard for her DPC clinic a block away from her old employer, to help her deal with a non-compete agreement. Not every doctor—or every person, for that matter—is built for the challenges of entrepreneurship.

Especially primary-care doctors who, for all their training, might feel guilty about charging patients directly. At the summit, the DPC leaders had to remind the audience, again and again, of the value of their skills. One doctor showed a photo of his plumber, who recently fixed a busted pipe in his bathroom. “This guy had no problem handing over an invoice for three hundred dollars for an hour of his time,” the doctor said. As he wrote the check, he told the plumber, “I didn’t make money this good when I was a family-medicine doctor!” The plumber smirked and replied, “Neither did I, when I was a family-medicine doctor!”

And then there was “The Dark Side of DPC,” a talk delivered as a monologue from a single chair, by a melancholy family doctor from the suburbs of Boston named Jeff Gold. Essentially, Gold mused on the challenge of being an introvert and dealing with the sheer onslaught of humanity in primary care. Most patients have some core fear they want to express, Gold explained, and part of our role as doctors is to locate and validate those fears. “Only now, I can tell them, ‘You don’t have to pretend you have back pain,’” he said. “Let’s have a cup of coffee, shoot the breeze. I don’t have to worry about what I’m going to code for. And it’s kind of fun to hear stories about the war and other stuff that happened before we were born.”

Still, being the container for those stories takes a toll, which for Gold sometimes manifests as a tongue-in-cheek aversion to people entirely. “One year for my birthday, the ladies at the front desk made me a picture frame with a message inside, which said, Do not book any patients with Dr. Gold for anything, at any time, ever,” Gold joked. “Some days I wake up and ask myself, Why did I go into medicine? Why not get a desk job somewhere, like in Office Space, and talk to my stapler? But deep down, I really do like dealing with people.”

Other doctors shared practical tips for dealing with the small percentage of patients who reach out constantly—like setting clear and realistic expectations, reinforcing those expectations in every email communication, and implementing tools like auto-responses and voicemail transcription software to handle requests that come in after-hours.

For patients who keep breaking the rules, behavioral contracts can help—like limiting phone calls to twice a week. “It’s like parenting,” said Delicia Haynes, a family-medicine doctor from Daytona Beach, who vows to empower, not enable, her patients. She isn’t afraid to dismiss patients from her practice who repeatedly violate the doctor-patient agreement. “I teach people how to treat me. Set boundaries, and remind patients that their choices have consequences.” For doctors who lack these skills, she recommends examining their motivations and insecurities. “Some people are nurturers. They like to be needed. So work on yourself. Can you get that need met some other way, not from patients?”

Michelle and I finally rolled up the gravel driveway to Lassey’s clinic, a gray, barn-like building which abuts a rolling pasture, with cows grazing nearby. Lassey greeted us in a Holton Direct Care T-shirt. “Come on in,” he said, waving us into the front room, which was adorned with reclaimed wood and farmhouse pendant lights. “A friend built the skeleton of the building,” he explained, “but I built everything on the inside.”

As Lassey gave us the tour, it was clear how much care he’d taken in designing the space. The hallway was decorated with a collection of vintage “Doctors Recommend” Camel cigarette ads; in the procedure room, supplies were meticulously organized inside a built-in wall of cabinetry; the phlebotomy area included a small framed sign that said All bleeding stops…eventually.

Lassey’s patients had left their mark on the clinic too. One patient plumbed the entire building; another donated limestone blocks for the retaining wall, and another let Lassey borrow equipment to move those blocks. A lawyer supplied the boardroom table in the staff room. A local artist contributed a painting in the lobby. “There was a smaller, identical version,” Lassey told us, “but I lost it at a charity auction to the hospital CEO—so she painted me another one.”

The clinic felt different than an ordinary medical office. It was brimming with personality, which highlighted another important element of DPC: It allows doctors to express themselves at work. After years of toiling away in a system which homogenizes both doctors and patients, seeing them as little more than “providers” and “consumers,” simple things like choosing a name, designing a logo, or decorating a space are subtle but significant ways for doctors to reclaim their individuality.

We settled into some low chairs in Lassey’s mental-health-counseling area, a spartan room he soundproofed with mineral wool. He told us about the arc of his career: his childhood dream of being a doctor, the impossible job he’d taken after residency, and the winter night in 2016 when he found himself hunched over what felt like the two-hundredth prior authorization of the shift and realized he needed to quit. “I filled it out, put it in my pile, slid a resignation letter under my boss’s door, and went home,” he said.

“I know Qliance failed,” I said. “But do you think DPC could scale across America?”

“I don’t know that it can be scaled up,” he said. “I mean, we’d all like to see that happen. But the truth is, I don’t know.”

And then, for the first time since I met Lassey at the conference, he looked tired. Between caring for patients, building and running his business, serving as president of the DPC Alliance, and being a husband and father, he seemed to be operating in a tenuous place.

“There’s a good chance that in a couple years, I might fade into the background for a while,” he said. “You know, help my kids with some stuff. Because this isn’t a one person, one leader thing—it needs to be a community.”

When I returned to San Francisco, it was cold and foggy. On Twitter, a doctor posted despairingly about his latest misadventures in prior authorization: denials, faxes, dead-end links, phone trees. Back on hold, he wrote. Listen to Hall & Oates muzak; are not soothed; Rick Astley comes on; feel strangely let down. Back home, I scooped up my daughter and inhaled the floral scent of her hair, wondering what kind of doctor she’d encounter when she needed one.

A few weeks later, I got an email from Michelle: What do you think about the name Canyon Oak Care? she wrote. Attached to the email was a three-page summary of the clinic she imagined: There are string lights outside, it said. I can make house calls as needed for homebound patients. I spend at least 30 minutes a day learning. I told her the vision was beautiful, but didn’t tell her that I doubted whether she could do it—whether she could really make it on her own. It seemed like she was standing at the base of a mountain and the summit was immeasurably far away.

Then I remembered the persistence of the DPC doctors. The sense of purpose and community in the hotel ballroom. Something was driving these people up the mountain—the new entrepreneur, doing a pap smear on the floor of an unfurnished exam room; the family doctor, pedaling her Velomobile to work at the crack of dawn with her strobe light on; the mournful introvert, listening to war stories over a cup of coffee, and then heading home to toss and turn in bed. For all of them, the DPC movement is both radical and vulnerable. Being among its people, even for just a short time, had felt a bit like holding a hummingbird—the soul of medicine, delicate and thrumming and inviolable. As one doctor put it, “You could pay me ten million dollars and I’d give it away and keep living in my camper and being a doctor. That’s how much I love medicine.”