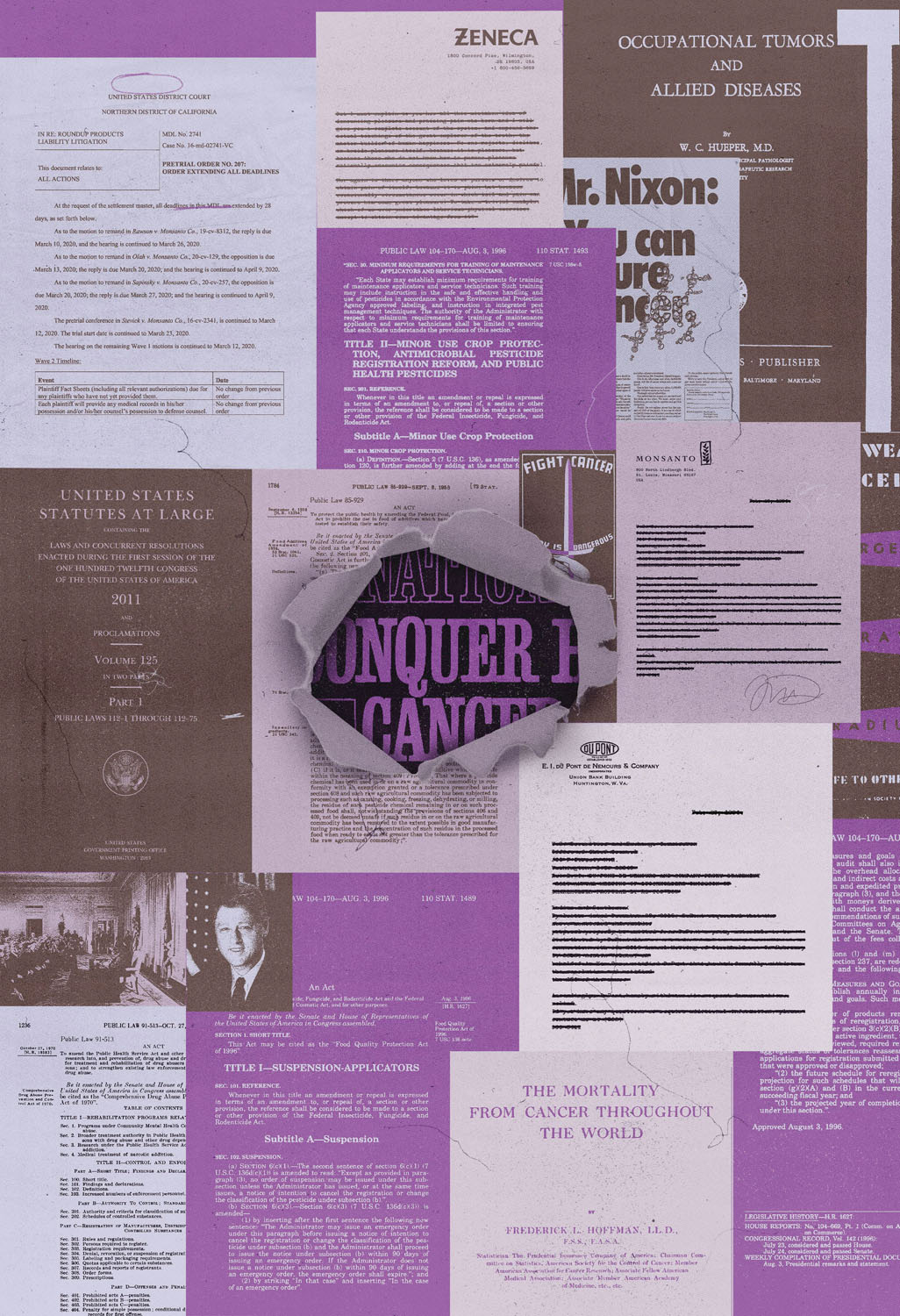

Profits and False Promises

How the war on cancer is good for business.

In the eerie, quiet week between Christmas and New Year’s 2021, halfway through a Fulbright to Hungary, I went to a medical clinic in Budapest to have a lump in my breast examined. I wasn’t too worried. I was young, it was probably a cyst. I just wanted to be sure. But then the ultrasound tech made a face—or, rather, she struggled to suppress one—and thus began my immersion in the cancer treatment apparatus. A week later, I flew back to New York and began my treatment. I was thirty-seven.

After my second dose of chemotherapy, hundreds of whiteheads broke out across my face, chest, and back. I considered this normal, since absurd and unpredictable things were happening to my body every day. But I dutifully reported it to the doctors anyway, as I’d been told to do with any new side effect. This one was taken more seriously than the others. The chemo regimen was suspended, and I was sent to an allergist.

The allergist told me I wasn’t allergic to the chemotherapy per se but to the steroids required to administer it. Paclitaxel, the generic drug I was on (brand name Taxol), contains an active ingredient by the same name. It also contains castor oil, an additive that improves the drug’s solubility in water, allowing it to effectively target cancer cells without requiring high, potentially toxic doses. Patients can experience hypersensitivity reactions to paclitaxel—anaphylaxis, in some cases—caused by either the active ingredient or the additive. To protect against this, patients are given Benadryl and steroids beforehand, a kind of pharmaceutical highball that puts you into a drowsy stupor during the treatment and keeps you up all night afterward.

My allergist submitted a note documenting my allergy to the insurance company, and I was switched to a different drug, Abraxane. Abraxane uses the same active ingredient as paclitaxel, but it is bound to albumin, a protein found in human blood, which means it is readily absorbed by the body and doesn’t require prophylactic steroids.

Why, I naturally wondered, wasn’t I given Abraxane in the first place? The next time I saw the one nurse who gave things to me straight, I asked her, and she rubbed her thumb and forefinger together. The insurance company won’t cover Abraxane until you have demonstrated an allergy to Taxol, she told me, because Taxol is so much cheaper. Abraxane’s high price tag comes largely thanks to its inventor, Patrick Soon-Shiong, the billionaire doctor, entrepreneur, and owner of the Los Angeles Times, whose successful corporate maneuver to crush the bioequivalent drug Cynviloq ensured a premium price for Abraxane.

There was nothing so surprising in this. Stories of cynical, inhumane decisions made by pharmaceutical companies at the expense of sick patients are commonplace these days. But the raw irrationality of it all, viewed in such close proximity to the real doctors and nurses injecting real drugs into my veins, was stunning.

Or perhaps I was just surprised that they were my veins to begin with. Perhaps I was surprised to be a cancer patient in my thirties at all, even though, as I would soon learn, breast cancer in premenopausal women has become increasingly common—so much so, in fact, that in 2024 the US Preventive Services Task Force revised its recommendations for mammograms to a decade earlier, advising women to start having them at forty rather than fifty. It’s not just breast cancer either. Between 1995 and 2020, overall cancer rates among Americans aged eighteen to forty-nine rose by 1 to 2 percent each year.

To be clear, a mammogram does not prevent breast cancer, so “preventive services” is a misnomer here. The biologist Sandra Steingraber has noted that the refrain “early detection is your best protection,” used to exhort women to receive regular mammograms, is actually a “non sequitur,” since “detecting cancer, no matter how early, negates the possibility of preventing cancer.”

The task force is far from alone in this euphemistic renaming: A much broader linguistic slippage has been at play for decades in the US, including when, in 1983, the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Control and Rehabilitation was renamed the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control; or when, in 1992, the Centers for Disease Control was rechristened the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

By 1995, the historian of science Robert Proctor had noted a growing trend among cancer researchers to talk in terms of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention, with “primary prevention” meaning something close to a traditional definition and “tertiary prevention” meaning regular old treatment.

“Prevention” came to dominate the nomenclature of cancer treatment at a critical juncture: It followed decisive political defeats of environmental legislation that could have put a check on industrial carcinogens. The prevention that would be trumpeted in the 1980s and 1990s was a far cry from the more militant prevention strategy being pursued in the late 1970s. Midwife to this awful pivot was the “war on cancer,” a rhetorical trope first used by the Nixon administration that has since clouded the waters when it comes to cancer’s causes and what to do about them. One could argue that, rather than being a war intended to eliminate cancer, the war has been a spectacularly effective distraction from addressing the influx of chemical and other industrial carcinogens that have become a seemingly ineradicable feature of modern life in the United States.

Since President Richard Nixon launched the war on cancer in 1971, politicians from both parties have consistently supported high levels of spending on cancer research. The National Cancer Act of 1971 unlocked hundreds of millions of dollars every year (mostly funneled through the National Cancer Institute) for research in universities, hospitals, cancer centers, and community clinics. Subsequent Congresses steadily increased all funding for cancer research, such that it rose from $500 million in 1972 to $6.5 billion in 2021.1

As the budget grew, the promise remained the same. Barack Obama encouraged America to cure cancer “once and for all.” George W. Bush campaigned on the promise of a “medical moonshot” to find cures for cancer and other illnesses. Bill Clinton called for a commitment to funding “research that once and for all can win this war.” George H. W. Bush and First Lady Barbara Bush launched “C-Change: Collaboration to Conquer Cancer.” Ronald Reagan defined success in the war on cancer to be a 50 percent reduction in cancer deaths by the end of the century, and set that as a goal. Every time a new president took office, he rallied the troops for this war. The war was premised on a promise: Cancer could be cured.

But buried beneath this evergreen drama of illness and cure, the promise of miracle biotech breakthroughs and heroic survivorship, is the story of how American business interests helped to steer politicians away from stopping the cancer epidemic at the source; how they helped to generate a mania for curing the disease and obstructed the analytic and moral clarity required to prevent it. Actually preventing cancer—far preferable to curing it, if less interesting—would mean asking why our cancer rates are so high in the first place.

It might make more sense to think about the promise to cure cancer less at the level of discursive logic and more as the inscription of a ritual, as an incantation or part of a liturgy. The cycle of repetition and failure has enriched this faith rather than eroded it, the way some cult leaders only consolidate their grip when the date they have predicted for the rapture comes and goes. This would be charming if it wasn’t so deadly.

Much of what animates the political enthusiasm for the war on cancer can be traced back to socialite and art dealer Mary Lasker. Like her husband, the ad executive who crafted the brand strategy for Lucky Strike cigarettes (“Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet”), Lasker had a gift for public relations. She was a New Dealer who turned her energies toward biomedical research as a next best way to get federal funding into American health care when President Harry Truman’s national health insurance proposal failed in 1946. In the 1950s, Lasker assembled experts to testify in Congress about the promising new field of chemotherapy. Their presentations highlighted one, tantalizing message: With adequate funding, a cure for cancer would be imminent. Most contemporary cancer researchers, as well as the scientific consensus of the time, vehemently disagreed. But it was an electrifying idea, so much so that it helped redirect attention from other perspectives on cancer—including what was causing it, and what might prevent it.

By the mid-twentieth century, scientists agreed that American cancer rates had been steadily rising since at least the turn of the century, and that one prominent culprit was industrial exposure to toxic materials. Aniline dyes, made from coal tar, were first linked to bladder cancer in workers in an 1895 study by a German physician. Subsequently, outbreaks of dye-related bladder cancer were found in Switzerland (1905), England (1918), the Soviet Union (1926), the United States (1934), Italy (1936), and Japan (1940). Each outbreak occurred ten to twenty years after the emergence of synthetic-dye production in a particular country, which pathologist Wilhelm Hueper used as evidence for the idea that, ordinarily, there is a certain “latency” period between toxic chemical exposure and the development of cancer.

Hueper, who had synthesized decades of medical literature on a range of industrial carcinogens in his 1942 book Occupational Tumors and Allied Diseases, was put in charge of the newly created Environmental Cancer Section of the National Cancer Institute in 1948. The section came into frequent conflict with corporate influences within government: In a 1959 memorandum, Hueper bemoaned being forced to delete manufacturers’ names from his reports. On the very day of his retirement in 1964, the section was shut down. By then, the public was well aware of the link between industrial products and cancer. In 1962, Rachel Carson had mainstreamed Hueper’s research in her bestselling book Silent Spring. Two years later, the World Health Organization declared that “the majority of human cancer is preventable.” Among the preventable carcinogenic exposures referred to in the report, some could be addressed behaviorally—by quitting smoking or avoiding sun exposure, for instance. But many of the preventable exposures pointed to by the World Health Organization were industrial exposures that lay out of the hands of individual citizens. Mitigating these exposures would require political will and, ultimately, federal legislation.

In 1978, under President Jimmy Carter, the US government took on the task of identifying top culprits responsible for the rising cancer rates. A report by nine scientists across three federal agencies found that the proportion of cancer mortality attributable to asbestos and other carcinogens frequently found on the job could rise to 40 percent over the next thirty years. The federal government seemed poised to leap from awareness to action.

But as this scientific consensus was building, industry groups began to martial vast resources toward shaping public opinion—and crushing legislation that would curtail carcinogenic products. The Council for Tobacco Research financed the work of more than a thousand scientists on basic cancer biology from the 1950s to the 1990s, hoping to introduce doubt into what had been a straightforward scientific consensus: Smoking causes cancer. The Asbestos Information Association worked to pathologize people’s fear of carcinogens, warning against “fiber phobia”; the president of the agrochemical company Monsanto diagnosed America with “an advanced case of chemophobia, an almost irrational fear of the products of chemistry.” The Nutrition Foundation—an industry group representing food and chemical companies—assembled a “fact kit” to repudiate Carson’s Silent Spring and distributed it to the entire membership of the American Public Health Association, as well as to health-care workers, public libraries, and other groups. The interests of the chemical industry were woven so deeply into the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act that one employee of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) joked that the act should have been named for the DuPont executive who combed through each line. The American Industrial Health Council, formed in the fall of 1977 by the Society of Chemical Manufacturers and Dox executive Paul Oreffice, managed to force the Occupational Health and Safety Administration to regulate chemicals individually instead of in generic classes, a method Labor Secretary Ray Marshall compared to putting out a “forest fire one tree at a time.”

But the most valuable weapon in corporate America’s arsenal against being held accountable for rising cancer rates was the war on cancer itself. Corporations took pains to derail the search for cancer’s cause but happily accepted starring roles in seeking its cure. After signing the 1971 National Cancer Act, Nixon named Benno Schmidt, a venture capitalist with strong connections to the petroleum and chemical industries, to head the President’s Cancer Panel. On the National Cancer Advisory Board, pharmaceutical interests made a strong showing; public interest and labor groups were totally shut out. The war, as many corporations saw it, could work magic for getting politicians to abandon a confrontational stance, since scoring political points for protecting American health could now be done far more easily: by funding cancer research. Without doing a thing to check corporate pollution, politicians could be seen as taking the cancer epidemic seriously. Thus, Reagan aggressively dismantled controls on air and water quality, occupational and consumer safety, and declared enthusiastically in 1988: “In the continuing struggle against cancer, Americans have put their trust in research.” The war would provide political cover that was irresistible to every subsequent president, regardless of party.

At a certain point in my treatment, the cancer began to be spoken about in the past tense. Tense is very important in cancer treatment circles, though anything but stable. “Survivorship” is a title technically conferred at diagnosis and lasting until death, perhaps to avoid confusion over whether one will, in fact, survive, and for how long. In my case, I know that tense mattered because it was not until after the chemo and surgery were over, and radiation was coming up, that cancer was being spoken about in the past tense, and that I thought to ask the surgeon, “Why do you think I got cancer?” She thought for a moment and then said, “I think you were just really unlucky.”

Was I unlucky? I think in some ways I was very, very lucky. My own treatment included a drug—Herceptin—that saved my life and wasn’t available to women as recently as the early 1990s. Ironically, given my skepticism over “war on cancer” rhetoric, Herceptin is one of the rare instances in which modern medicine has done exactly what the rhetoric suggests that breakthrough cancer drugs can do: make a diagnosis that was once a death sentence survivable. Most breakthrough drugs in this field share price tags similar to that of Herceptin——tens of thousands of dollars—but prolong life by mere months, not years.2

It might make sense to think about the promise to cure cancer less at the level of discursive logic and more as the inscription of a ritual, as an incantation or part of a liturgy. The cycle of repetition and failure has enriched this faith rather than eroded it.

I’ve come to reject the concept of luck as it applies to my own carcinogenesis. If anything, I have come to prefer the version of the luck argument offered by the epidemiologist Richard Doll: That it is those who are exposed to carcinogens and don’t get cancer who are the lucky ones.

Many people I told about my cancer asked me if I had it “in my family.” The fact that cancer is so random, and so common (about half of us will get it, but there is no way to tell which half), inspires fetishism and blame. These can take the form of an immediate search for ways in which the newest cancer patient you know is somehow not like you—because they grew up in the Midwest, not the Northeast, or because it is “in their family,” or because they don’t exercise. Anything to feel in control. Obviously, I too wanted answers. I did not, in fact, test positive for either of the BRCA genes, which predispose one toward breast cancer.

As industry faced fewer and fewer checks, the war on cancer reached ever further into the cultural consciousness. From the mid-1980s to the mid-aughts, as Samantha King writes in Pink Ribbons, Inc., corporate philanthropy was transformed from an unscientific, sporadic activity into a highly calculated marketing strategy—cause-based marketing. The cause par excellence was breast cancer. An alliance of pharmaceutical companies, mammography equipment manufacturers, and cosmetics companies, along with large cancer charities like the Susan G. Komen Foundation, as well as the media, helped to transform breast cancer into a brand, one with which corporations, politicians, and consumers were eager to associate. Buying a Yoplait yogurt or an Estée Lauder anti-wrinkle serum with a pink lid was presented as a way for ordinary Americans to engage in combatting a deadly disease.

For politicians, the fight against breast cancer became a safely nonpartisan issue. It was a women’s issue that wasn’t divisive, like abortion was. Breast cancer’s victims were construed as “innocent.” Their loudest advocacy organizations were led by middle-aged, white, and middle-class women, presented as groups of mothers and wives: women, not feminists. In 1996, conservative, anti-abortion politicians Rick Santorum, Jon Kyl, and Ted Stevens all targeted the “breast vote.” The 1997 passage of the Stamp Out Breast Cancer Act was celebrated as a great bipartisan unifier. “This exhibition of unity is really what this Congress is all about,” said then-Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX). Representative John McHugh (R-NY) spoke of “the bipartisan tragedy that this disease can bring.” For all of its fanfare, the actual content of the act was fairly modest: the creation of a breast cancer stamp, which required the US Postal Service to divert sale proceeds to the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Defense, allowing consumers to directly “fight” cancer by contributing their small change to the federal cancer research program.

Politicians in the age of the war on cancer needn’t take on the difficult work of regulating carcinogens in order to be seen as cancer warriors. A politician who would rather not cross Monsanto/Bayer, Dow, or the American Chemistry Council doesn’t need to. They can just slap on a pink ribbon. In 2023, scores of bills to regulate toxic “forever chemicals” died in Congress with help from Republicans who had also enthusiastically backed a major cancer research funding package in 2016.

If war-on-cancer rhetoric helps politicians avoid hard choices, it helps the rest of us to live with the contradictions of American capitalism writ large—to focus on biotech breakthroughs rather than our abandonment by legislators. We need this coping mechanism all the more acutely because government’s inability to effectively regulate exposures to carcinogens has left the United States drenched in chemicals the rest of the developed world has banned. As of 2019, eleven agricultural pesticides approved for use in the US are banned or being phased out in China; seventeen in Brazil; seventy-two in the EU. The Department of Health and Human Services’ National Toxicology Program publishes a biennial list of about 250 carcinogens to which the average American is exposed—neglecting to mention that, among the eighty-six thousand consumer chemicals registered with the EPA, a majority “have never received vigorous toxicity testing,” according to an investigation by the Guardian.

Even when a substance is known to be toxic or carcinogenic, corporate pressures often delay or prevent it from coming off the market. The most recent and tragic demonstration of governmental paralysis has been the case of PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals.” According to a study published in the Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology last January, PFAS exposure through drinking water is clearly linked to increased risk of cancer. But regulating PFAS has proved difficult. In 2021, industry killed the PFAS Action Act, which would have directed the EPA to take regulatory action on air and water pollution limits for two of these substances, PFOS and PFOA. The act passed the House, then got stuck in the Senate’s Environment and Public Works Committee—two thirds of whose members received campaign donations from PFAS manufacturers. Finally, in 2024, then-President Joseph Biden’s EPA established regulations setting limits for six PFAS in drinking water, but just over a year later the agency announced it was withdrawing those limits for four of the six chemicals and would extend deadlines for compliance on PFOS and PFOA limits in drinking water.

No amount of vigilance, no set of consumer or lifestyle choices, can completely shield us from environmental carcinogens, if only because of the geographic breadth and longevity of these materials. Radioactive debris from the first atomic bomb test in New Mexico ruined photographic film at Kodak in Rochester, New York; in New Hampshire’s Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, researchers found nearly one pound per acre of DDT and over two pounds per acre of PCBs, neither of which were ever used on or even near the forest.

This health crisis, and the average citizen’s powerlessness to fight it, generates immense anger. For more than fifty years, the war on cancer has proved a durable way to channel that anger away from corporate culpability. President Donald Trump has begun to dabble in abandoning that method, cutting billions of dollars in cancer research in the first few months of his second term. This may be because he has found another effective conduit in Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the Secretary of Health and Human Services, who is highly skilled at marshalling Americans enraged by the health-care system and by environmental pollution into crusades that pose no real threat to industry. He has harnessed the suspicion among many that the health-care and pharmaceutical industries prioritize profits over health (true), that the environment has something to do with epidemics (also true), and he has warped this righteous anger and incipient activism into a political force that can accept and even applaud Trump, who in his second term is working at full tilt to make the environment more toxic to human health.

Create an enemy, rally people in the name of that enemy, and never hurt the bottom line of American chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturers. It was the modus operandi of the war on cancer, and remains so for the current administration. It is lethal theater, in some ways a continuation rather than a rupture with the political tradition of paying lip service to public health, while allowing corporate interests to call the shots.

The president’s cuts unfortunately coincide with a new area of focus in cancer research, on what experts call “the exposome”—the totality of environmental exposures one has throughout their life, including while in the womb. According to a recent Washington Post article, researchers are looking back at the 1960s through 1980s—when industrial and other environmental exposures associated with modern life exploded—to explain the puzzling increased cancer rates among young people. This type of investigation, into complex sets of causal chains, is decidedly not the type the president seems to favor. Rather, he is drawn, like many leaders before him, to the more scintillating promise of a miracle cure.

Trump’s second term has also seen Soon-Shiong, Abraxane’s doctor-investor-billionaire creator, rise from the ashes, due in no small part to how adroitly the businessman has rhymed his messaging with war-on-cancer rhetoric, mirroring its relentless optimism and showmanship. Like the war itself, Soon-Shiong has shown an uncanny ability to convert the tragedy that attends this disease into fantastical promises and huge profits. In 2015, two years after then-Vice President Biden’s son Beau was diagnosed with glioblastoma—an aggressive brain cancer linked to burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan, where Beau was deployed—Soon-Shiong met with the Biden family and eventually presented the vice president with a two-page proposal for an immunotherapy initiative that would use genome sequencing to create individualized cancer treatments. He called it “The Moonshot Program to Develop a Cancer Vaccine.” Biden was convinced, and he brought the administration along with him. In Obama’s final State of the Union Address, he announced an anti-cancer initiative called “Moonshot” that would “make America the country that cures cancer once and for all.”

“I’m putting Joe in charge of Mission Control,” he proclaimed.

Politicians in the age of the war on cancer needn’t take on the difficult work of regulating carcinogens in order to be seen as cancer warriors. A politician who would rather not cross Monsanto/Bayer, Dow, or the American Chemistry Council doesn’t need to. They can just slap on a pink ribbon.

Biden, in turn, placed Soon-Shiong on the advisory panel for Cancer Moonshot in 2016, even though a whistleblower lawsuit had already alleged that Soon-Shiong’s start-up NantHealth broke health privacy laws and engaged in “a multitude of fraudulent activities.” Soon-Shiong used his role in the 2016 Cancer Moonshot as a marketing scheme for his business interests even as independent reviews found that “the data don’t back up the hype.” When Biden announced his plans to “supercharge” Moonshot in 2022, Soon-Shiong had faded from the scene. But Biden didn’t question the basic model of partnering with private industry. In 2023, his administration announced the launch of CancerX, a public-private partnership that will work, according to its website, to “harness our collective superpowers.”

Soon-Shiong directed his LA Times editorial board not to endorse for the 2024 presidential election, hoping to cultivate ties with Trump as cozy as those he enjoyed with Biden. In February 2025, Trump’s FDA authorized an expanded access program to ImmunityBio, another pharma venture by Soon-Shiong, allowing it to go forward with limited distribution without the rigorous clinical trials required of new pharma products. In June, ImmunityBio settled a securities fraud case related to misleading statements about the FDA approval changes for one of its drugs. In September, a STAT article noted that clinical trial results touted by the company “do not support” Soon-Shiong’s claim that ImmunityBio’s drug extended the lives of patients with advanced lung cancer.

When I finished chemo, surgery, and radiation, I was put on the drug tamoxifen, an endocrine disruptor with a host of mild to severe side effects, including, ironically, an increased risk for a rare and aggressive uterine cancer. Some of those who are prescribed this medication find its side effects intolerable. So, much like 42 percent of the women prescribed it, I stopped taking tamoxifen within the first two years—even though it had been prescribed for ten—thus forfeiting the benefits of lower recurrence rates it offers. Patients who cannot handle tamoxifen aren’t necessarily people who can’t stand discomfort—most of us have just gone through chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. For me, the last straw was that I lost the ability to find words. Words are my vocation. Their loss brought tamoxifen’s tally to my career, my emotional well-being, my intellectual life, my physical comfort, and my libido. There wasn’t much left to work with.

One of the more perverse features of making endocrine therapies like tamoxifen the centerpiece of “prevention” strategy is the fact that many of the known, legal, carcinogens present in American life are endocrine disrupters to begin with. Certain common insecticides are designed to disrupt the endocrine function of insects. Other synthetic organics (synthetic as in engineered in a lab, organic as in contains carbon) are endocrine disrupters by accident, a fact discovered by two cell biologists who were studying estrogen’s relationship to breast cancer. The scientists noticed cancer cells in dishes to which no estrogen had been added dividing rapidly, as though they had been hormonally stimulated. The culprit turned out to be nonylphenol, a chemical added to plastic to prevent it from cracking, which had shed into the blood serum from its plastic storage tube, and which turned out to be estrogenic.

The risk of dying of cancer has declined in the past thirty years, the American Cancer Society tells us. But the good news about survivability tends to be misleading. Heightened testing regimens mean that many nonaggressive or indolent cancers (those tumors destined to remain small and harmless over the life of the patient) are detected and also produce diagnoses earlier than by symptom development, both of which juke the statistical “survivability” of cancer in a positive direction.3 Lung cancer, which remains as deadly as ever, is less common because of concerted anti-smoking campaigns. These campaigns were arguably the most effective intervention into cancer rates of the entire war-on-cancer era, and they focused on eliminating the carcinogen rather than submitting the patient to gruesome, expensive cures. The steady rise in cancers among young people will hold the real answer to where mortality rates are headed. Will the young people survive their cancers, or won’t they? And at what costs?

Let’s not forget that inventing a cure isn’t the same as giving Americans access to one. Miracle cures mean little for the uninsured. Many Americans diagnosed with cancer cannot pursue treatment, or pursue it only at the price of bankruptcy, since cancer disproportionately affects the poor, whose neighborhoods are more likely to be zoned industrial, to be downwind of air pollution, to have contaminated water. (A 2016 paper in the Journal of Clinical Oncology concluded that going broke paying for treatment “appears to be a risk factor for mortality.”) The poor are also more likely to serve in the military, which brings the potential for high-level exposure to carcinogenic agents, or to do agricultural labor that demands proximity to cancer-causing pesticides.

We will continue to seek innovative cures for cancer, because we are going to keep getting cancer. If all chemical plants ceased production tomorrow, if the whole load of carcinogens already dumped into the environment could be magically removed, preexisting exposures to carcinogens would still cause millions of new cases—cases stored in bodies now—that deserve medical treatment of the highest order. Re-evaluating the war on cancer does not mean simply letting the sick die. It means coming to understand the “race for a cure” as utterly senseless without a parallel race to stop dumping carcinogens into soil, water, air, bodies, and lives.

1 Adjusted for inflation, this represents an increase from $3.3 billion to $6.5 billion.

2 Another way to describe this luck would be to say I am lucky I am white. Despite the white, middle-aged face of the 1990s breast cancer efforts, it is disproportionately young Black women who die of breast cancer, who are more likely to have the diagnosis “triple negative,” which simply means the cancer is negative for estrogen receptors, negative for progesterone receptors (in other words, not eligible for treatment with hormone therapy), and negative for HER2 (not eligible for Herceptin). It means there are two powerful ways doctors know to treat breast cancers (outside of the standard suite of chemo, surgery, and radiation), but neither of them applies to this type.

3 The false perception of improved cancer survival rates often stems from two related biases: lead-time bias and length-time bias. Lead-time bias creates an illusion of longer survival because earlier detection starts the survival clock sooner. For instance, two patients who develop and die of cancer on the same days may appear to have different survival times if one was diagnosed early through screening and the other later by symptoms. Length-time bias occurs because screening disproportionately detects slower-growing, less aggressive, or indolent tumors, while rapidly progressing cancers are typically diagnosed once symptoms appear. The result is that screening can seem to extend survival when it actually identifies cancers that already have better prognoses.

Max-O-Matic is a designer, illustrator, and collage artist based in Barcelona. His clients include BMW, Netflix, and Panenka. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, National Geographic, The Washington Post, and New York magazine.