Missing History

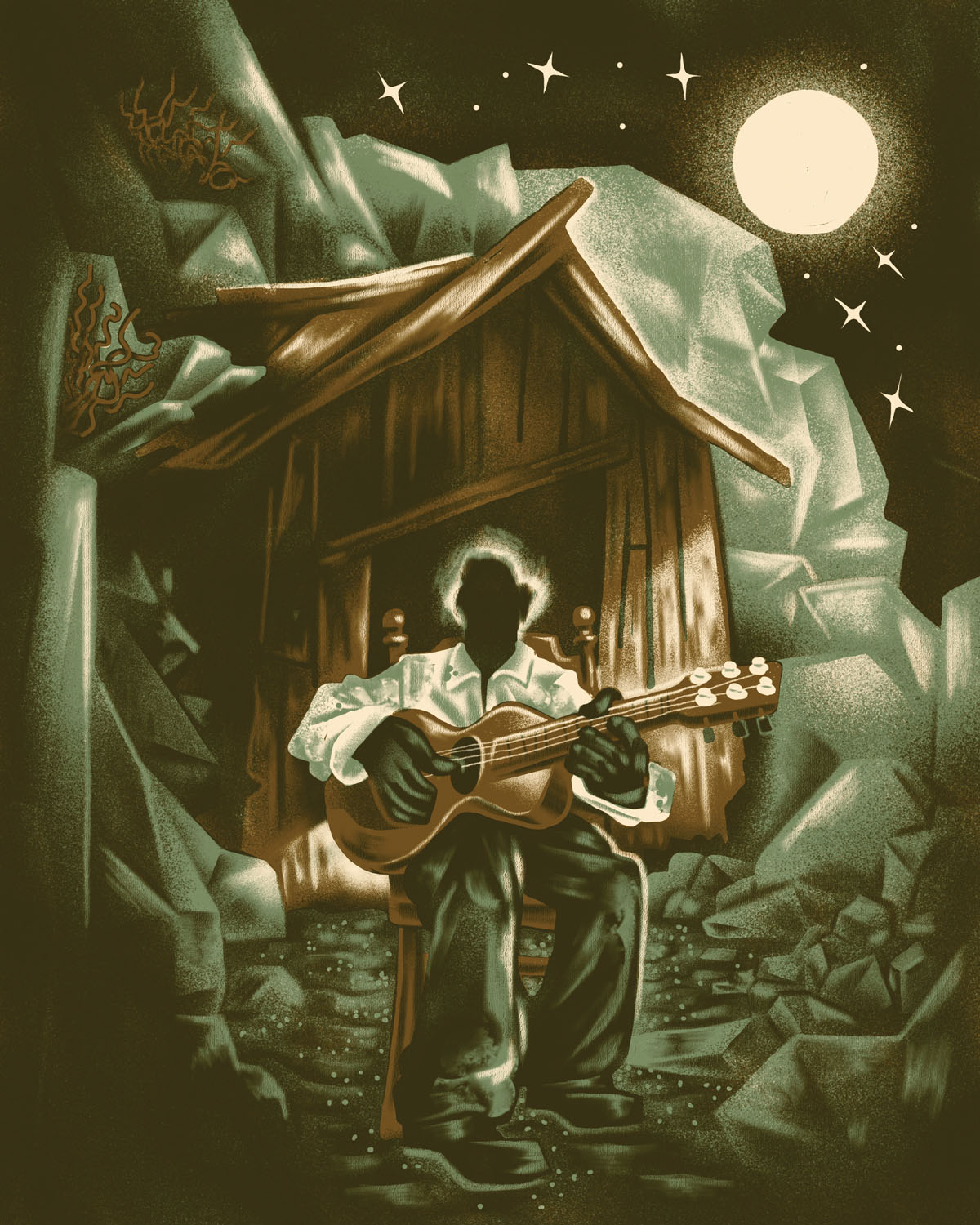

Melon Floyd was born out in the Salts, 1881, in the border country between Winnemucca and Susanville—before they recorded Black voices on acetate, before his knife-throwing contest with Charlie Long, before “Laughing Man Blues.” His father was Terry Floyd, a freed slave and smuggler who hid out in the Salts for thirty-six years before the Reno law flushed him from the mountain crags. His mother was Anne Smith, who died while in labor.

Floyd was a sickly boy, an asthmatic. When he was four, his father sent him to Susanville, a flat country where the air wasn’t so thin, to live with his grandmother. He was schooled out of a single history book, sang in the church choir. By Floyd’s sixth birthday, his grandmother had saved enough to send away for a pine guitar from Sears-Roebuck.

When he was thirteen, he left home.

There are no known photographs of Floyd. Some sources say he was a mulatto. Others claim Anne Smith was half-Shoshone. Letters from the period describe Floyd as having a fat, abnormally large nose and small, narrow-set eyes. When he spoke, his voice was high and nasal.

I had first heard about Floyd at a cocktail party five years ago; some Top 100 rock star was releasing an album “reimagining” Floyd’s work. The apartment was a five-flight walk up with bad air and poetry graffitied on the bathroom walls in permanent marker. Late into the night, the woman throwing the party took me to her room and played me three minutes of “Laughing Man Blues” on an antique reel-to-reel.

“Is this him?” I asked her.

“No, this is a cover from the late seventies.”

I remember we were sitting on a mound of coats and purses on her bed, trying to get comfortable. There was a guitar playing, and someone slurring something I couldn’t fully make out. The woman had her eyes closed, nodding her head to the rhythm, running her hand up and down her long, white neck. I lay there in my shirtsleeves, sweating, watching her.

After the song had ended, she opened her eyes.

“Isn’t this the saddest thing you ever heard?”

I didn’t say anything.

“No one gets it at first. Then one day, out of the blue.” She smacked her hands together.

From overhead, the Salts looked like clusters of broken bottle glass, nestled along the river trails of the Tohakum and the Fox Range. Deep brown veins ran through the mountain passes. Smuggler traps—narrow, slippery footpaths hemming the mountain wall. Some extended and looped for miles, curlicueing back into itself. “Desperados” like Terry Floyd had memorized the traps to avoid getting lost or swallowed up by the abyss below. In the 1950s, teenagers were disappearing or turning up dead so the state finally walled up the entrances.

The plane climbed above the cloud line; I felt my ears seal.

In 1964, social historian Lester Meeks flew from Minnesota to Wyoming as part of a six-month anthropological project recording oral histories from the area’s native Indian communities. It was in Medicine Bow, Wyoming, that Meeks encountered ninety-two-year-old Charlee Ree, whose account makes reference to an “itinerant outlaw musician” from the Susanville-Honey Lake Valley area. According to Meeks’s notes, he had found Ree “holding court outside the Smith & Smith Drug Store. By her own account, she had moved [to Medicine Bow] when she was thirteen; her father was a rancher and her mother was a school teacher. She has eleven children and twenty-six grandchildren. When I found her, she was diabetic and had claimed to have lost most of her vision.”

I have heard Meeks’s tapes, currently archived in the Hunter College library in New York City. Despite her age, Ree answered Meeks’s questions clearly and in full. She talked in what I would describe as a soft squawk. Her life history in and of itself is underwhelming, except for a fragment of conversation transcribed here from Tape MBWY-012B—00:24:05:

Meeks: ...and what was your father like?

Ree: (laughs) I adored him, of course. Don’t all daughters adore their fathers? But he didn’t like that I was wild. That I had a wild side. Didn’t like any of my boyfriends.

Meeks: You had many boyfriends?

Ree: I wouldn’t say many. Not as many as you think. Just boys, you know. But then there was one...I remember. Talking of fathers, his daddy was a bad man. What you might call an outlaw, from out in the Salts. You know where that is?

Meeks: I don’t. No.

Ree: It doesn’t matter. But this bad man’s son, he had the most gorgeous guitar he’d play for me.

Meeks: That’s sweet. (indistinct)

Ree: He’d play the kind of way where everything kind of sat still. It didn’t matter what it was, what the words were, or how it sounded—every time he took that guitar out, it’d carve me up inside.

Meeks: That sounds beautiful.

Ree: It was beautiful, but it was ugly too. Being seen like that…it scared me.

My first night in the motel, the couple in the next room fought all night. I could hear their voices abstracted through the walls. I pressed my head into the pillow or moved so that my head was at the foot of the bed. It was useless. I went into the bathroom, splashed my face with water. Even with the tap going I could still hear them.

I dug my tape player from my bag and slipped on a pair of headphones.

The recording goes like this:

A woman reads out “‘Laughing Man Blues.’ New York City. 6 January 2009. Track 4829C.”

There’s a low click.

The song starts up all fire and brass. The drums are smashing down and the singer starts singing, “Worry worry worry.” And there are about a dozen guitars all thrumming down at the same time, and there’s even an organ way back there somewhere. From this confusion, the track slides into the B section. Verse Verse Chorus Verse. No hesitation. No reluctance. The singer feigns a Southern drawl and the instruments surge against each other.

The song keeps going, and it’s easy to lose my place, trying to lift the noise off the song, trying to find Floyd under all that thrashing. First it was in the horns, and then the bass, and then the singer, but the changes come too quickly and then it’s gone. The noise overtakes the track, smothers Melon Floyd, and already my mind is on something else.

Floyd fell in with Charlie Long wrangling stray cattle on Lake Havasu, on the California side. Long was older, more seasoned, and he managed their wages. They rode during the day and camped at night. It was with Long that Floyd developed his trademark musical style. Before meeting Long, Floyd played mostly gospel songs. It was Long who brought Floyd’s style out of the church, teaching him songs that were “grittier” and “leathered…with some chew” according to some sources. Melon’s songs became fatalistic, revisiting themes of suicide, alcoholism, infidelity, and damnation.

In a letter to his mother, Long wrote:

…and sometimes I could hear him over on his pallet. He was muttering and mumbling dark, mad things. About the rope and the knife. I thought maybe he was having a nightmare and didn’t pay any attention, but the next morning, Floyd would take that old resonator of his and start playing. It was the same words as during the night, put to song instead of fits and mumbles.

Honest to God, Mama, if the man can do that laid down, I’d hate to guess what he’s capable of standing up.

As the months drew on, the relationship between Floyd and Long became more contentious. Long grew increasingly jealous of Floyd’s talent and began to withhold his wages. Tension between the two mounted. They fought constantly over money and women. By January 1897, after their last contract had expired with the neighboring ranchers, they went their separate ways.

Floyd and Long met again in August at Lady Ursula’s, a brothel in Mohave County, Arizona. The story goes that Long had heard one of his songs being played from the inner parlor at Lady Ursula’s. By then, Long had become an opium addict, having fallen in with Chinese coolies who’d worked the railroads in California and Canada. He was erratic and quick to temper. Long charged into one of the rooms and found Floyd with his guitar, entertaining a group of businessmen.

The two fought. Floyd’s guitar was smashed to bits, and Long lost two teeth. When the two men were finally pried from each other, Long challenged Melon to a knife-throwing contest for the sole claim to work the territory between Oregon and Mexico City.

The two men were to stand at opposite posts with a single throwing knife each. Whoever struck the other’s post first was declared the winner. Despite his addiction, Charlie Long was still a crack shot and a fast draw. At the start of the contest, Long pierced Floyd’s throwing hand, pinning it against the post with an eight-inch Bowie. Floyd stayed in the hospital three weeks, as doctors struggled to bring down the inflammation. He ran a high fever and treated the severe pain in his right hand with morphine tablets. By the time he was well enough to be released, the hand was useless.

After Meeks’s death in 2000, his original field notes and tapes resurfaced. By then, the name Melon Floyd, though still obscure, had made the rounds through certain historical and musical circles. A connection was made between the Wyoming woman and the blues musician. Historians and archivists descended on Medicine Bow to flesh out Charlee Ree’s story.

Floyd arrived at Medicine Bow in May 1897 with a secondhand C. F. Martin parlor guitar. He worked as a street musician, playing outside churches up and down the main street, strumming through the tight pack of gauze on his picking hand. He was harassed by local police, arrested twice for “making an unruly display on a public thoroughfare.” During a brief stint at the jailhouse, he was advised by the local attorney that there was “honest work to be done” at the nearby Bascomb Ranch.

He was hired on for three dollars a day haying, but having no prior farm experience, was injured almost weekly. He sliced his hands often and popped his shoulder out on numerous occasions from mishandling a workhorse.

It was John Bascomb’s daughter, Charlee, who tended to Floyd’s injuries, and sat up with him afternoons while the other men were out working. At the time, she’d been married just a year to Louis Steven Ree, a cattle broker eighteen years her senior, whose work took him between Wyoming, Idaho, and Nebraska. Floyd wrote songs for her. Sometimes, Charlee would sing for him.

Rumors circulated about their relationship. The other laborers were irritated by Floyd’s uselessness as a field hand, which left more work for the others. He worked only half days because of his injuries. Some suspected that he took to injuring himself just so he could spend time with the Bascomb girl.

I suppose they at least had the summer. Floyd slept in the cowshed some evenings. On cool nights, the smell of manure wouldn’t be as suffocating, and if there was a wind, it would unsettle the flies and keep them from landing on him while he slept. I imagine she snuck out at night to meet him. Perhaps she’d take him tenderly, mindful of his bruises and cuts and wrenched muscles. Then it’d be arms into arms, legs to legs, their two breaths collapsing together. For a time.

By the end of the hay harvest, John Bascomb was fully aware of what had been happening between his daughter and Floyd. Those who knew Bascomb say he was an even-handed man but had a volcanic temper. When he was agitated, he could be a taskmaster, even cruel. He’d insult his field hands as a whole, berate them. Did he see his daughter returning from the cowshed one early morning? Did she stroll in that dreamy way people do, loping, back to her house?

On the last payday of the season, John Bascomb assembled a posse comprising six of the sheriff’s men and half of his field hands. They waited for Floyd at the front of the house. Charlee watched from her bedroom. One of the men fired a shot—some say into the air, some say at Floyd.

Floyd fled, guitar in tow, and the posse pursued. Somehow he gained enough distance to lose them. After spending the night and the following morning hiding in a culvert, Floyd caught a mail train out of Wyoming. He returned to Medicine Bow two months later.

What happened next with him and the Bascombs and Louis Steven Ree—that account is available, along with Meeks’s notes, at the Hunter College library on 68th Street and Lexington Avenue, third floor. You can find out yourself. That’s not really the kind of story I want to tell.

September 12, 1900, Floyd’s name turned up in an account book with the Salvation Army stationed in Galveston. According to a chart filled out by Lieutenant Cora Mayhew, M. Floyd was treated for lacerations of the neck and face, and an abscess of the tooth and gums. He was administered doses of morphine and a topical antiseptic, but a misdiagnosed eye injury resulted in the degeneration of the retina in both the left and right eye.

It is unclear if Floyd was already in Texas when the hurricane blew in from the Gulf or if he went to Galveston to take advantage of disaster relief in the area, but the flood of tens of thousands of refugees and injured strained the resources of the Salvation Army crisis center. Records show that Floyd complained of an “eye-ache.” Nurses applied a salve of mercurochrome. Two days later, his day nurse reported an 80 percent loss of vision.

It was during his recovery that Floyd wrote “Laughing Man Blues.” He sang in the wards and in the halls for nickels:

I turn my head and what a sight there is to see.

I turn my head and what a sight there is to see.

I want to be a laughing man

So no man turns his head to laugh at me.

His singing came to the attention of Private Ernest Low, of Canton, Massachusetts. Low was a volunteer in the Galveston disaster-recovery effort, filling out damage assessments and survey charts for various districts in the city.

There is a picture of him in the Library of Congress—young, shaven, wearing rubber waders. The gray water reaches just below his waist. A clipboard and small pencil are balanced on top of his head. He faces the camera, and his cheeks dimple as if he’s unsure how to smile. Behind him is a small wood-frame church—the boards ripped apart, exposing its skeleton in parts.

On weekends, he played the cornet in the Salvation Army band. He met Floyd in the ward, and soon they would spend their time together writing songs and talking about music. None of their collaboration survived the years except for “Laughing Man Blues.” Low was credited for the original instrumentation of the song but was later censured for his involvement with secular music.

After Floyd was discharged, he relocated to Houston. Three months later, Low quit the Salvation Army and followed him.

I drove past the motel to a bar in Susanville, a nowhere kind of place in the basement of a pizza parlor. There were pipes on the ceiling, and every now and then I could hear the water rushing overhead. The radio from the pizza parlor was tunneling down. I was the only one there, and the bartender didn’t pay me any attention. He just put a bowl of peanuts in front of me, took my drink order, then went over to the other end of the counter and stayed there with his paper. I took out my notes and started going over them.

I unfolded a map and spread it on the counter. In pencil, I drew a line tracing Floyd’s path, scratching out his name in capital letters out in the Salts, then a line to Susanville, Lake Havasu, Medicine Bow, then Texas.

The door opened and a kid with slicked-back hair and a leather jacket looked around the bar. He waved to the bartender, then sat down next to me. He was talking to the bartender, who grunted but didn’t look up from his paper. He turned to me.

“You here for the show?”

“No,” I said.

He explained how he was the manager of a punk band. He talked excitedly about changing the sonic landscape, about Joe Strummer, Black Flag, the Misfits.

I nodded but didn’t say anything.

The bartender came back with a beer and the kid upturned it into his mouth, wiped his lips with his sleeve and said, “What are you, on vacation or something?”

“Not really,” I said.

He put a finger down on the map, on the Salts.

“Melon Floyd.”

“You’ve heard of him?”

“Shit, yeah. He’s like my distant grand cousin or something.”

I looked at the kid. He was white with green eyes and gelled blond hair. He took a fistful of nuts and pushed them into his face.

“Most people don’t know who he is,” I said.

“Most people are idiots.”

We tapped our empty glasses together.

“Are you really related to him?”

“Sure. Grew up on the family legend. Pops was a punk original. Even the way he went out.”

I knew the story. Low went to Houston to record three songs for the United States Gramophone Company, “Laughing Man Blues” among them. He found Melon panhandling in a bus station in Jeanetta. Passengers waiting for their connection would throw change at him and Floyd gained a reputation for being able to find his coins by sound alone, diving to the floor, underneath chairs and benches, or pressed under some man’s boot. He looked by listening, they said.

Floyd was living out of a YMCA on Fannin Street. His clothes and linens were in tatters and infested with mites. Low reported the ammoniac smell of cat urine in his room.

Low took pity on Floyd. He promised to take Floyd to the radio station and split the proceeds for the recording. He pressed some money into his hand for a cab and made plans to meet him at the studio the next day.

It was June and a freak snowstorm blew in from the east with a record snowfall of over four feet. Three days later, after the thaw, they found his body outside the YMCA, four dollars crumpled in his good hand.

“Are you really related to him?”

“My mother’s side,” he said.

“You don’t look it.”

He shrugged. The band came into the bar, each of them in leather and chains, and bright glowing loops in their ears, or chins, or eyelids. They started setting up on the other side of the bar. The kid excused himself.

They played an hour set. What they lacked in talent they made up for in volume. Midway through, they turned the dial all the way up, and they smashed down on their instruments hard, and the air crackled in my ears. I drank a few more beers, but I couldn’t get into it.

After the set, the manager bought everyone a round, me included. I sat and drank with them, not really saying much but not really listening either.

They asked about me. How I liked the show, where I was from, what I was doing here, how long I planned on staying.

“Not long,” I said. “I’m thinking of leaving in the morning.”

“Have you been up to the mountains?” the manager asked.

I told them I hadn’t.

They all made a noise like what a shame.

“You gotta go before you leave,” the drummer said.

The manager looked at his watch. “It’s only two. We can get up there before dawn.”

The band seemed to think it was a good idea. They raised their glasses to it.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Drink up,” the manager said, opening his wallet and signaling to the barman.

We left my car where it was and piled into the back of their van. I was wedged behind a large amp while the band members took pulls from an emergency stash of vodka. The air was muddy with smoke and it was getting hard to keep my eyes open. I could feel the pressure change as we curved up the mountain.

“Almost there,” the manager said from the front seat.

The band members cheered.

We drove for maybe another hour when the engine cut.

“We’re here,” he said.

We were parked by the side of a steep road, up against a guard rail. The manager had a flashlight and he flicked it on, cutting the beam across the ground a few times.

“This is it?” I said. I looked around. Our breaths exploded from our lips. There were pines drooped over the road and the mountain wall rose up thick and black.

“No, no. We’re going into the traps,” the bassist said. He finished off the vodka and threw it into the dark. I heard it smash.

We followed the manager’s light over the guard rail and into the shrubs. The trees whipped a little at us, and sometimes we had to stop for a band member to piss. We could hear the wet hitting the stones, running. Then we’d continue. Soon the path met the mountain wall again.

The entrance was boarded up with wooden beams with the words keep out stenciled over it. The manager tucked the flashlight under his armpit and vaulted over the top. We followed him.

The footpaths were not as narrow as I imagined. Two of us couldn’t walk shoulder to shoulder across, but it was comfortable enough for one with maybe a good foot of leeway on either side. The manager went first, cutting off the flashlight.

“It won’t do us any good here,” he said. “Just keep your hand on the wall.”

I did like he said and followed behind the rest of them.

There was nothing to hold onto along the smooth rock wall. I listened to their footsteps ahead of me, tried to picture their bodies moving through the dark. One of them sang a song I didn’t recognize, one their own songs, I guessed.

It went on for hours, me following behind them, tracing the cold, gripless wall, the crunch of sand and dirt under my shoes. The dark stretched out forever. My back was covered in sweat, and when the wind blew down on us, I could feel my muscles wanting to seize. “We’re lost,” someone said. “Shut up, no we’re not.” Another said, “Just admit it.” But none of them would admit it. At some point we stopped moving and waited for someone to say something. I could hear them breathing. I stood there staring out into the blackness, my back against the cool rock face, not knowing how far down it went or for how long.

Ricardo Diseño is an illustrator and poster designer based in Austin, Texas, who has done work for The New Yorker, the Criterion Collection, The New York Times, Chronicle Books, and many other clients.