The Woman Wong

The summer I got engaged, I flew from San Francisco to London to see my mother. I had to remind myself during the flight that the engagement’s being a big deal didn’t make the trip a big deal, and that I should treat it like any other visit. Sure enough, my mother and I fell into the same routine as always: morning tai chi in the garden, errands, and evenings absorbed by her favorite soaps and quiz shows. A pile of unmarked student essays sat in my lap while I fidgeted with my engagement ring, wondering why she hadn’t asked to see it yet.

Some mornings we took the tube to Chinatown to her favorite dim sum place, Jade Garden, where we’d sit and read our newspapers, sometimes in silence, sometimes pausing to mention something from an article we’d just read or to murmur general satisfaction with the food. The rest of the time we followed our own agendas: She had her charity-shop volunteering and tai chi group and other social activities, while I had old friends from university days to catch up with. I smiled through their dinners and toasts and their fawning over my modest ring, but would spend the tube ride home feeling oddly empty and restless.

I suppose I’d allowed myself to hope that the engagement might provide a sort of backdrop to our three weeks together. But two weeks in, there were still no inquiries about the wedding, no morsels of matrimonial wisdom or fretful concern. I reminded myself not to begrudge or question her silence on the subject except for when I’d first called her with the news, which elicited nothing more than an “Ah, really? That’s good.”

By now, I was somewhat accustomed to her strange brand of cheerful detachment, which seemed to have emerged after my father’s death two years earlier. I call it strange because, up until then, she’d maintained a rigorous practice of calling her children several times a week without regard for time zones (my older brother lived in Shanghai, the other in New York). During these calls, she would demand detailed updates on our lives—and each other’s—and dispense advice or admonitions about our health, finances, and relationships. Among her many opinions, she found her Caucasian daughters-in-law to be spoiled and inconsiderate, and my boyfriend-now-fiancé, also Caucasian, too immature and therefore unreliable. As kids, my brothers and I often wondered why she couldn’t be more like our kindly, placid father. He never imposed his will when it came to key decisions in our lives—which extracurricular activities to choose, which subject to study at university, which person was or was not appropriate future spouse material—and would respond to any solicitation of opinion with some variation of the same answer: You’re smart or You’re more educated than your father or You know what you’re doing. His noncommittal attitude was a blessing when we were children and rebellious teens, and was occasionally maddening as we grew older. In any case, our father’s implicit acceptance was consistently counteracted by our mother’s interference. For years we tolerated her overinvestment in our lives with complicated feelings of resentment, guilt, and frazzled humor. I don’t think any of us ever imagined living without it.

At our father’s funeral, my mother cried into her tissue, laid weakly comforting arms around me and my brothers, then quietly withdrew from our lives. She no longer asked us for anything, no longer expressed dismay or approval about the choices we’d made, instead migrating to a state of sunny dispassion that my brothers and I agreed was a natural—and, we assumed, temporary—response to bereavement. We thought that she simply needed some time before she could come out of it and be our mother again.

Eventually we had to admit to the possibility that this was who she was now. We had to put aside our expectations of her, my older brother said, and let her do whatever she needed to get on with her life. The only thing we could do, short of moving back to England (none of us seriously considered it), was simply to make ourselves present and available to her through regular phone calls and visits. I agreed—what else was there to do?—but had struggled in recent years to live without claim to her concern.

But on the morning before I was due to return to San Francisco, as I watched my mother pushing and folding air around the garden, I was provoked by a last-minute impulse for change. I suggested that we forgo our usual Chinatown dim sum and told her about Bambu, a fusion place on Goodge Street that a friend had recommended. It was supposed to be a bit pricier, I said, but the food was meant to be lighter, the ingredients fresher, and, well, wouldn’t it be good to try something different? There was a chance she might hate it, I warned.

In one flowing move, she raised her right knee, swung the leg out in a gentle sidestep, and with her loosely cupped hands sliced the air diagonally before twisting her hands like an unfurling flower. I was so transfixed by the quiet force and control of her movements that I’d almost forgotten I was awaiting her answer.

She finished her sequence, let out a breath, and said, “Okay, Daughter. Why not?”

As we walked from the tube, I quietly fretted that I’d made a mistake, that my mother would object if the restaurant were too much of a departure from the traditional dim sum experience. To my relief, the place wasn’t too sleek or westernized; instead, its sparse modernity blended easily with familiar Chinese motifs rendered in warm rosewood. Even the young, kung-fu-attired staff was a curated mix of East Asians and dark-haired Caucasians.

We ordered my mother’s favorites: har gow, cheung fun, lor bak go, choi sum, and even foong jow, which I was pleasantly surprised to find on the menu. When the food arrived, I expected my mother would criticize the fussy presentation—the deconstructed har gow was a yin-yang disc of shrimp and pork sitting atop a pleated dumpling skin, and the lor bak go came in delicate radish-shaped slices—but thankfully, she seemed merely amused by it and agreed that, overall, the food was decent. Our only real complaint was that there was nowhere to hang our coats, which kept sliding off the end of our backless circular bench or being knocked to the floor by wait staff rushing past. The choi sum dish, thin and stringy, also got a thumbs-down.

“Grown here,” said my mother, her sorrowful tone suggesting that the poor Chinese vegetable didn’t stand a chance of growing to its full potential on foreign soil. When I was younger, I might have taken this as a veiled slight.

We ordered a plate of mango pudding to share (my mother was watching her sugar intake), and once the waiter had left I said, “So, Mamee-Ah…”—I was attempting something close to a jovial lightness in my tone—“how do you feel about your only daughter getting married?”

It sounded as forced as it felt, and I blushed at my clumsy appeal for her interest. My mother appeared unfazed; she picked up her chopsticks and popped the last har gow in her mouth. She chewed slowly for a while, a thoughtful look on her face.

Then she asked, “How much do you and your fiancé earn?”

“What?”

“Your fiancé works, yes?”

“Yes, yes he does,” I said. I was unprepared for the bluntness of her question and how it elicited from me the same defensive, cagey stance I’d adopted in the past. I took a deep breath, reminding myself that she wasn’t being rude, merely seeking confirmation that my fiancé and I were stable. That it must have meant that she cared. Still, I couldn’t bring myself to give up that kind of detail about our relationship; it would have felt like a small yet significant betrayal.

“Well, we have enough for the house, of course, and basic needs. And some savings?” I sounded like a hesitant contestant on a quiz show. Sensing this wasn’t quite enough, I added, “And we don’t really spend on luxuries.”

My mother nodded, apparently satisfied. She gazed around distractedly for a moment, then picked up a menu from the unoccupied table behind us, a gesture that seemed to indicate the end of the discussion.

“Don’t worry,” I smiled, patting her hand. She didn’t look worried. “He’s very responsible in this way. And he’s very caring. I wouldn’t marry him if he wasn’t.”

She put down the menu, her fingertips lightly resting on it. I felt that I should say more.

“And he doesn’t use his skateboard anymore.”

She looked puzzled. “Skateboard?”

“Remember how you said it was a sign of immaturity? Or that he must be too poor to pay for the bus?”

My mother surprised me with a girlish sort of giggle. “Did I really say that?”

“Yes. But he has a car now. And he got a promotion at work.”

“As long as he treats you well.”

“He does.”

“Well, good then,” she nodded. “Most women aren’t as fortunate as you. Ah, here’s our mango pudding.” My mother eyed the fist-sized orange blob on the plate. “Hmm. It’s not very big.”

“No, it isn’t.” I didn’t know if I was relieved or disappointed that her attention had turned from me to the pudding.

She picked up one of the spoons and gently pressed the back of it against the pudding to test its firmness. “I’ve told you before, haven’t I, about the woman from my old village?”

“Which one?”

“Surname Wong. A very unfortunate woman.”

My mother hadn’t told me village stories for years, but I remembered that they tended to be on the long side.

“Maybe we should eat this slowly?” I suggested.

“Why?”

“Well, if it’s a long story, I’d feel funny sitting here without any food on the table.”

Now that we were approaching noon, the restaurant was busier than when we came in; every table was full, and a small clump of waiting customers had formed in the entrance.

My mother took a chunk out of the mango pudding. “Not bad. Go on, try some.”

I took a small spoonful, then, as the waiter passed us, ordered a pot of green tea from the menu.

“Wong was her maiden name,” said my mother. “Wong Man Kiu. Her family was too poor to keep her, so when she was eight, they married her off to a family from my village. They had her betrothed to their nine-year-old son.”

She sighed, shaking her head. Although child brides were a part of life in those days, my mother, herself betrothed at thirteen to my father, could never mention the subject without acknowledging the ache of separation involved for the girl and her family. It usually came down to economic necessity on the girl’s side and preservation of lineage on the boy’s, though sometimes a family just wanted an unpaid servant and farmhand in one living under their roof. From the bits and pieces my mother had told me over the years, I gathered that all three happened to be true in her case, though she maintained that our father (much to my disbelief) had in fact stood up to his overbearing parents in her defense when it counted.

In the case of the woman Wong and her betrothed, she said, rather than wait until they came of age, the boy’s family decided to throw the wedding party straight away. The ceremony was followed by a simple feast attended by guests from their own and neighboring villages.

I asked my mother why the boy’s parents were so impatient to have the wedding ceremony.

“It’s hard to say,” she replied. “Maybe they were superstitious. Sometimes the parents believe that if they don’t do it as soon as possible they might not live to see it happen.”

I pictured the stream of lai see passing into the hands of the parents, each red envelope stuffed with money. I imagined firecrackers, musicians, men full of drink, and boisterous congratulations. And in the middle of it all, two small figures bundled up in their wedding outfits, the girl standing like an extra waiting for her cue, the boy sullenly jutting out his chest, as if he wanted to keep the giant corsage strapped across it as far from his face as possible.

“After the ceremony,” my mother said, “they were officially announced husband and wife, but they slept separately until they came of age. The girl would have been eighteen, the boy nineteen. On the auspicious date that had been chosen, the elders pushed the two of them into the boy’s bedroom, which was now of course the wedding chamber.”

“I suppose everyone was listening at the door,” I said with a grimace.

“That’s how it was in those days,” said my mother.

Some time later, the woman Wong fell pregnant. Her husband kept coming to her for sex, but she was full of nausea. She acquiesced once or twice, but after that she refused him.

One morning her husband announced he was going into the city. When he failed to return at the end of the day, she went to the rice fields and asked her mother-in-law what to do. “Men will go off sometimes,” the older woman replied, not once looking up from her digging. (Her own husband had left several years before, taking with him most of the lai see money from his son’s wedding.)

This was the 1960s, when work was scarce in the New Territories. More and more people from the villages were going into the city to look for work. The woman Wong was probably hoping this was the case for her husband. However, when he still hadn’t returned after a week, her hope and concern gave way to mundane tasks. She occupied herself by looking after the house and working the small family plot, where she helped her mother-in-law grow rice and vegetables to sell at market. The two of them managed to get by on their meager earnings and passed their evenings in companionable silence, mending a garment or rubbing ointment into tired joints while listening to the radio.

Several months went by, and still no word from her husband, although rumors floated around that he was staying with a woman in another village. The woman Wong bore a son, and lived under a mantle of pity bestowed upon her by her neighbors, who came with gently probing questions and, from time to time, donations of a chunk of salted fish or a basket of mandarins.

One autumn night, her husband came back. He looked at the baby sleeping in the bassinet by the fire and marveled at the child’s likeness to him. When his wife demanded to know where he’d been, he fell into a foul mood, started searching the kitchen for his bottle of rice wine, found it, and pushed her into the bedroom. She awoke the next morning to the sound of rattling. Her husband was trying to work the lock of the wedding trousseau chest that he’d pulled out from under the bed. He said he needed money, and couldn’t she spare a couple of gold bracelets for him to pawn? After she chased him out with a broom, he stayed away for almost a year.

Upon his next visit, in late summer, he expressed mild surprise at the presence of two infants by the fire, once more pushed his wife into the bedroom, and left the following morning. This became something of a pattern; the woman Wong had four sons in almost as many years, and a trousseau chest with a broken lock.

“One time,” said my mother, “I saw her chasing the scoundrel up the hill road, crying and cursing at him until she caught up with him, tackled him to the ground, and wrenched her gold bracelets from his hands.”

She chuckled loudly at this recollection, a throaty, gleeful cackle that I hadn’t heard in years, and which made the couple from the next table glance over.

“So you see, she had some fire in her! In fact, she was a smart, capable woman in many ways. When she married into the family, she knew nothing about farming or running a household, but after some time she learned how to do it all very well. She even taught me how to fix the hole in my roof. I really couldn’t understand how a bright woman like that could tolerate such behavior from her husband.”

A waiter returned and set down the pot of green tea in front of us.

“So then what happened?” As invested as I was in her friend’s fate, I was beginning to wonder where this story was going and what it had to do with my engagement. My mother was telling me about an abused, neglected woman the day before I was due to fly back to my fiancé. Was it amounting to some kind of cautionary tale about the perils of men and marriage? My instinct to take offense softened against my curiosity—was this an attempt at mothering me again?

“Well, I dreaded getting roped into other people’s affairs, but in this case, I really saw her sinking deeper and deeper.”

“What did you do?”

“One afternoon we passed each other on the hill road and stopped to chat. When I asked how things were going, she burst into tears and said, ‘Not good, not good.’ When she’d finished crying, I told her that she couldn’t go on like this, letting him come home whenever he felt like it and leaving her with nothing but another mouth to feed. I suggested that she find a way out, save up some money so she wouldn’t have to rely on his measly scrap of land.”

“How did she take it?”

“Well, she didn’t say much, just listened, really. I told her about my machinist job at a garment factory in Kowloon. The money was decent. I knew she’d pick it up quickly. I told her I could put a word in with the manager. She said she’d think about it.”

The next few times my mother saw her, she asked the woman Wong if she’d given any more thought to her suggestion. Each time, the woman Wong appeared uneasy at being reminded of their conversation and gave the same reply: She needed more time to think.

The months that followed saw no change, until the evening her husband returned. As soon as he came in, he blew out the oil lamp and told her to hurry and check all the doors and windows. Then they sat in the dark. Eventually they could hear footsteps and voices outside.

“No lights here.”

It was a woman’s voice, smoke-heavy and thick with agitation.

“Check around the sides and back.”

“What kind of trouble are you in?” whispered the woman Wong. Her husband pushed his palm over her mouth. Spots of light moved over the windows, which began rattling and thumping. Crying started from the back room where the boys slept. The rattling and thumping stopped for a moment, then started back up, more loudly and insistent than before. Above the din rose the woman’s voice: “Leung Chi Wai! If you’re in there, you’d better come out!”

“What’s going on here?” The woman Wong’s mother-in-law had wandered out into the front room. To the darkened figure of her son, she said, “I suppose this is your doing.”

The woman Wong told her to go back to the boys’ room and make sure they didn’t come out. Then she lit the oil lamp and said to her husband, “Open the door, before they break it.”

At the sign of light, the rattling and thumping died. Her husband edged himself around the front door, squinting against the bright beams that landed on him. Two dull-eyed thugs, each wielding a flashlight, flanked a stout woman in a fur coat. Neighbors had gathered outside, a safe distance from the scene, and their torches cast a faint, flickering light on the house.

“Leung Chi Wai!” growled the woman. “Didn’t I tell you the next time I caught you sneaking back to this dump I’d cut both your legs off?”

The woman Wong’s husband attempted to stand his ground, but when he spoke his voice was thin and wavering. “She’s my wife, Sister Ping. Surely I can come and see her now and again?”

“You have no wife! I’m your only woman!” Sister Ping appeared to be craning for a better view of her lover’s wife, who remained inside the front room of the house. “Now, are you going to come quietly, or do I need to put my boys to work?”

The woman Wong’s husband raised a hand in surrender. He turned in the direction of his wife, his silhouette hunched in fear. Then he stepped, haltingly, toward the throng of lights.

After he had left with Sister Ping, the woman Wong came to the doorway, and the spectators, feeling the incongruity of their presence, lowered their torches and scattered back to their homes. To the woman Wong they looked like stars unfastening from the sky.

“The woman was with some gang or other,” said my mother. “He probably built up gambling debts in the city and had to become a kept man.”

“Sounds like he got what was coming to him,” I said, draining my cup of tea. “I guess that’s kind of a happy ending?”

“Wait, I haven’t finished yet,” she said. “There’s more.”

After this incident, the woman Wong no longer accepted her neighbors’ visits or inquiries. She leased out her husband’s farm, left her sons in the care of her mother-in-law, and found casual work on a Kowloon construction site. The journey into the city was an hour bus ride each way along bumpy hill roads, and the work was tiring and monotonous; whole days spent breaking, hauling, and mixing cement. She worked ably and diligently, though, and after several weeks the boss began giving her regular hours.

For years the woman Wong worked hard to support all the bodies under her roof. The four boys grew, standing head to shoulder. They purged their restlessness by tearing all over the village, clambering along rooftops, throwing rocks at wild boar in the mountains—whatever would wear them out by the end of the day. They seldom heeded their grandmother, who half-heartedly bathed, fed, and scolded them when they returned panting and dirty for dinner. They heeded their mother more; basking in her general, weary affection, her rare outbursts of wrath had much more resonance. Life continued in much the same way, until the arrival one day of a letter:

Dear Wife

I have been in England these last few months. I’m working in a friend’s restaurant. The pay is not bad, and I’m learning some English. Here’s some money for you to buy food and things. Please look after Mother and our sons.

Your husband,

Chi Wai

Inside the envelope was a ten-pound note, the equivalent of half a week’s wages. It was the first time she’d received any money from him. The woman Wong put the letter and the bank note in her trousseau chest and carried on as before. After a month, she finally took the note to the bank. She wrote a brief reply to her husband, telling him that his mother was in good health, the boys were well-behaved, and that she would put the money toward their schoolbooks.

Their correspondence continued for some time, always with the same, slightly shy formality. Past offenses were not mentioned or alluded to, except perhaps the one instance when she gently inquired about his intentions to return to Hong Kong. His reply, written a month later, was that it “wasn’t convenient” to do so.

“I don’t know if it occurred to her that he might have gone to England to escape Sister Ping,” said my mother. “We barely crossed paths during that time; we were both working so much. But when I saw her during the lunar new year celebrations, I asked how she was doing and about the situation with her husband. All she would say was that she didn’t want to dwell on the past. I think she was just happy to hear from him regularly, and to get some practical contribution to the household. Apparently he was talking about bringing the whole family over to England.”

“Don’t tell me she took him back,” I groaned. “I don’t think I could bear to hear it.”

“She couldn’t if she wanted to anyway,” said my mother. “A waiter at his restaurant told him about all these rumors he’d been hearing from the village. People were saying that his wife had run off with another man. A cement worker, from the construction site.”

“Was it true? I’ve got to say, I wouldn’t blame her.”

My mother shook her head and glanced away, seemingly occupied with some new thought. I noticed the music in the restaurant had stopped and realized I hadn’t a clue what had been playing all this time.

My mother pushed the plate of mango pudding toward me. “Finish it,” she said.

“I don’t want it. It’s too sweet for me.”

“Finish it, Daughter. Don’t waste it.”

I gave her a look and grudgingly forced a small spoonful into my mouth. As I washed it down with tea, my mild annoyance subsided; it was the first time my mother had bullied me into eating since my father died.

“I’ve always thought,” said my mother, “that her husband reacted quite strangely to this news.”

“About the affair?” I said.

“He didn’t even write and ask her about it. He just went right ahead and filed for divorce. Another strange thing is that he didn’t tell her himself. He wrote to a female cousin in Kowloon, who had to go back to the village and break the news to his wife. The two women barely knew each other.”

“That is pretty strange. And so the divorce, it went ahead?”

“Yes. And she ended up having an affair after all.”

I widened my eyes in excitement, as if I’d found the answer to a riddle. “The cement worker!”

My mother nodded. “They even got married in the end.”

“Ah,” I said, glad that the woman Wong had finally got her happy ending. I reached for the teapot and gave it a shake. I poured a little into my mother’s cup, and the last of it into my own. The waiter briskly removed the pot before she could turn the lid out.

“Wait—” She caught him as he turned to leave. “Fill it up with water, please?”

“Sorry, no refills here,” he said, not looking sorry at all. “You’ll have to order another pot.”

She frowned at him, and he went on his way, knocking our coats off the bench as he brushed past. My mother waited until I’d picked them back up, then said, “The second husband was pretty bad too.”

“No!”

“He was a feeble-minded man who grew more superstitious the older he got. Soon after they married, he saw a fortune teller who told him he wouldn’t live to see forty-five. The idiot believed it, of course, and that day he went home to his wife and announced that he wasn’t going to do another day of work. What was the point, if he was only going to live to forty-five? And you know what his grand plan was? Stay at home, cross his arms, and wait for his destiny to catch up with him! So from that point onward, the woman Wong had to work twice as hard to support her no-good husband and her kids.

“I was in England when this was going on. All of this I heard from the village grapevine. About ten years later, I made my first trip back to Hong Kong after emigrating here. This was in the early eighties. I heard things hadn’t been so good for her. She was living in Kowloon with her husband and sons, who he ordered around like coolies. He yelled at them and beat them for the slightest reason. When the oldest son was sixteen, he left home with so much resentment that he broke off all ties to his mother.

“I managed to get in touch with her, and we met up for dim sum. She wanted to hear all about England and about you kids. She kept asking about me and my life, but there were so many things I wanted to ask her. We hadn’t been talking for more than half an hour when she said she had to get going. She said her husband had a temper, and he didn’t like her having friends. She had to tell him she was going to buy groceries just so she could come out and see me. My throat’s getting dry from all this talking.”

My mother took a gulp of tea. “So when she got up and pulled her handbag over her shoulder, her shirt sleeve rode up and I saw the bruises on her arm.

“I called her number the next day and her husband answered. When I asked for Wong Man Kiu, he started shouting and screaming, ‘There’s no one of that name here! No one! Whoever you are, don’t you dare call here again!’ My hands were shaking afterward. I’d never heard someone so angry.”

My mother held up her hands as if in surrender. I clasped them with my own and set them gently on the table.

“Did you ever get ahold of her again?” I asked.

She shook her head.

“I suppose her husband made it difficult,” I said.

“I don’t know, Daughter. I didn’t call again.”

“You didn’t?” I took my hands away. “But why not?”

My mother looked at me helplessly. “I don’t know. Perhaps, after that call, I thought he’d given her another beating. Perhaps I didn’t want to get her into more trouble.”

“You could have helped her,” I insisted. “She listened to you before, right? About working in the city?”

My mother let out a long “Ayy…” shaking her head in what looked like resignation. I wanted her to say something else about her friend—that yes, she remembered now, she had in fact called her again and offered help. I wanted her to remember something hopeful that she’d heard from the village grapevine: that the woman Wong finally escaped her second husband’s tyranny, that she left him, or that he really did meet his destiny at the age of forty-five. That she’d married again, and that her third marriage was a good one, finally. (Or, more likely, another unhappy variation on her previous marriages. No, I didn’t want to think of her continuing like this over the years, each new man adding to her store of struggle and sadness.)

Amid the growing clamor of the restaurant—I realized we were now in the thick of the lunch rush, voices fighting to rise above each other, customers lined up outside—my mother and I sat in silence. I cradled my teacup in my palms, taking lukewarm sips now and then.

If there was no happy ending for the woman Wong, I thought, was she merely a victim of circumstance? Or was it a consequence of bad luck or judgment? Did the woman Wong suffer from too much or too little hope? Or did she, like her second husband, believe in destiny, and that she had to accept hers, even if it was one without happiness?

As I waited for my mother to say more about the woman Wong, not knowing yet that I’d already lost her, she picked up the spoon that was resting on her napkin and gently took the plate of mango pudding from me.

I feel a little foolish when I describe what happened next, but at the time it jolted a visceral, pit-of-the-stomach nausea in me that, on reflection, forced me to accept the terrible fact I’d been avoiding: My mother had stopped truly caring about anyone else—about me—after my father’s death. That was just how it was. I had no power or right to make it otherwise. So the following summer, when I flew her out for the wedding, I wasn’t upset when she laughingly mangled the blessing during the hair-combing ceremony, or when she took the envelope of milk money from her new son-in-law without a single tear or even a small sigh of lament during this symbolic transfer of her daughter’s care. When I had our first child, I didn’t complain that she rarely asked about her granddaughter over the phone or showed no interest in making a visit. A few years later, when I was going through chemo for breast cancer, I wasn’t angry that she didn’t call, except to tell me I shouldn’t plan a visit that summer, as she was joining her friends on a cruise.

So what happened was this. As my mother began scraping the last bits of mango pudding with the edge of her spoon, I saw a strange transformation in her face: Her eyes were shining, suddenly bright and naked with hunger, and her lips were pressed together in a satisfied, girlish sort of smirk as she swallowed the last morsels of sweetness. The woman Wong had disappeared entirely from her mind, which was now occupied with this mango pudding that could not go to waste, and which, confident in her abilities, she knew she’d get clean off the plate with her short, sharp strokes.

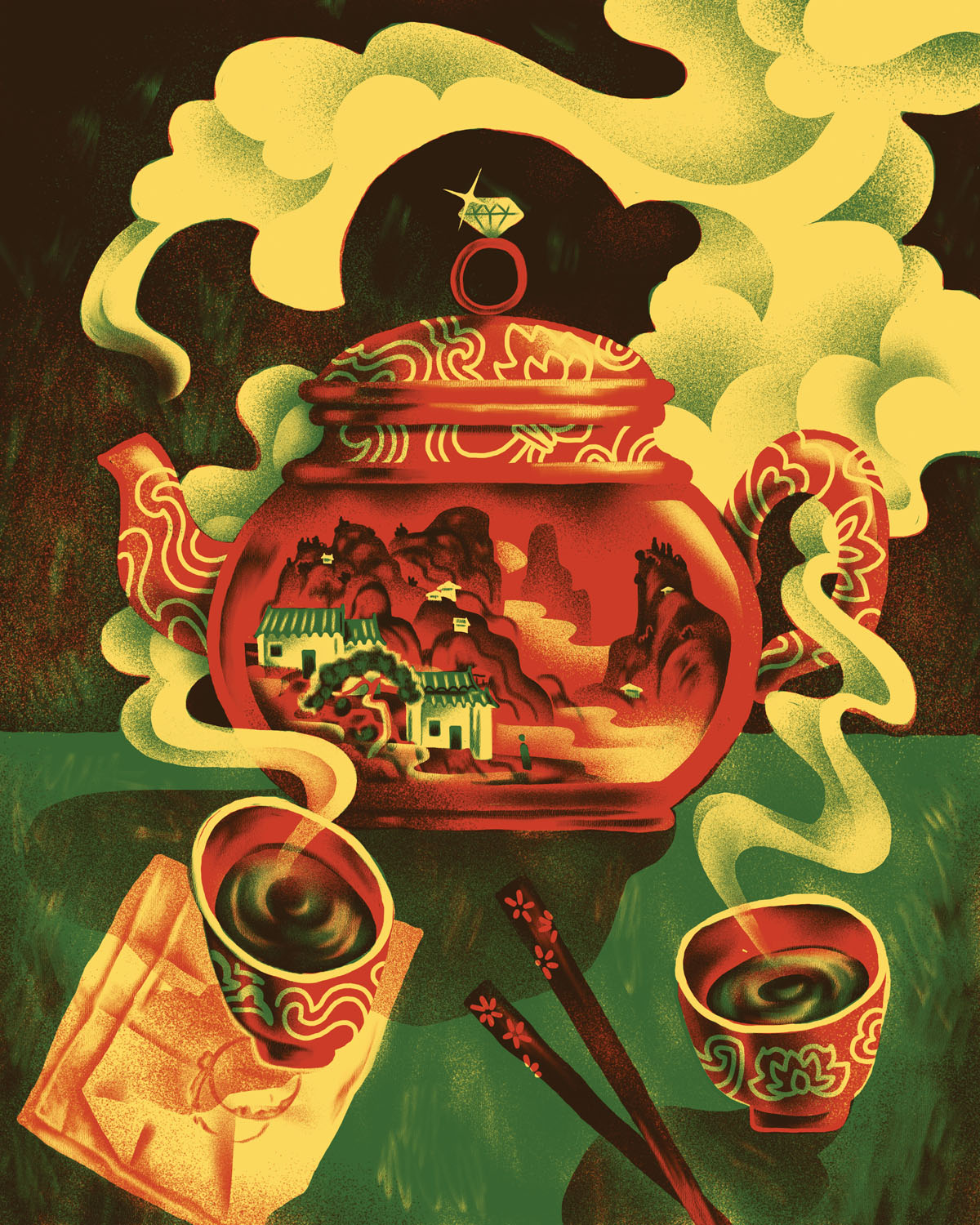

Ricardo Diseño is an illustrator and poster designer based in Austin, Texas, who has done work for The New Yorker, the Criterion Collection, The New York Times, Chronicle Books, and many other clients.