Epistolary Evidence

Correspondence across a century reveals the nuts, bolts, and then some of a magazine.

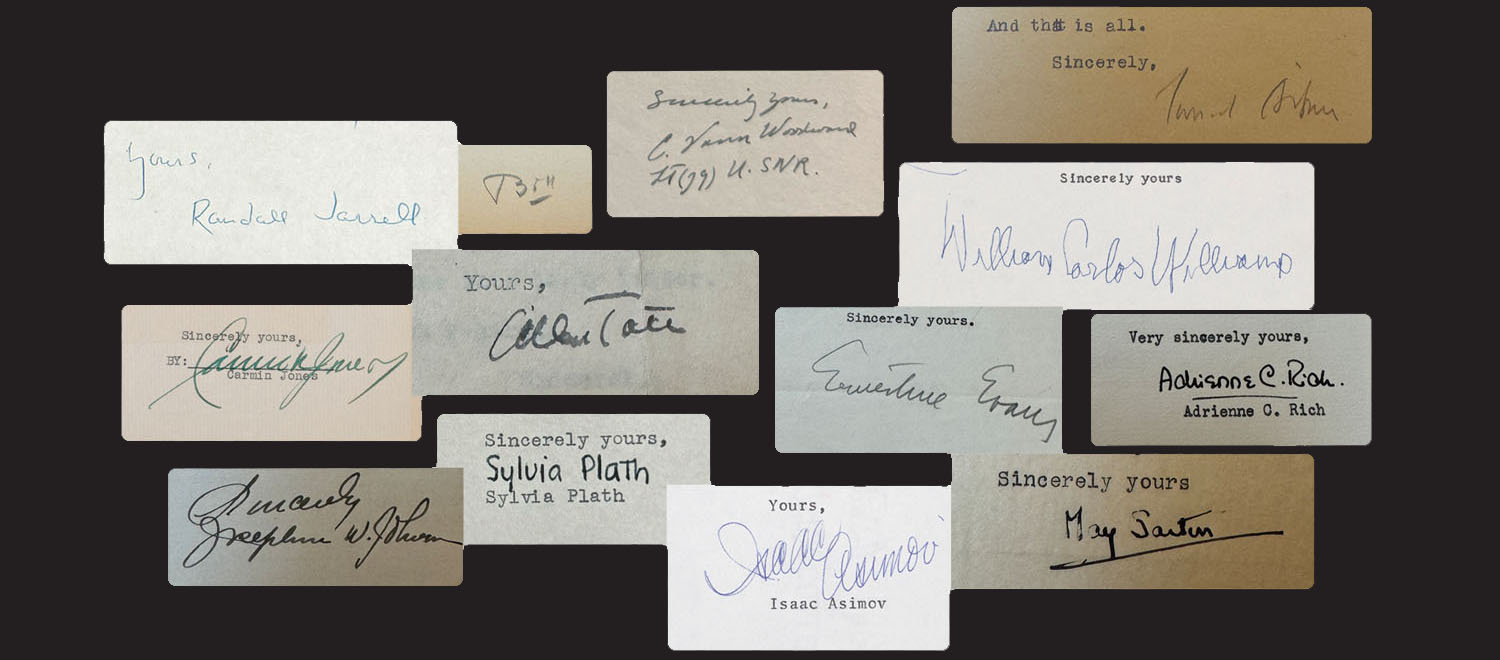

The writer Leslie Jamison is a good friend of mine. She’s also a contributor to this magazine whose work I’ve edited for more than a decade. Future archivists mining the VQR records will find years of emails in which we discuss our growing and shrinking families, a house fire (mine), a new couch (hers), migraines (mine, Joan Didion’s, Virginia Woolf’s), book tours (hers), men in and out of our lives, and “moving to a sleepy beach town and opening a bookstore together.” Of course, we also correspond about story ideas and deadlines, edits and proofs. The hundreds of hours I’ve spent in the VQR archives tell me I’m not alone in enjoying such a warm relationship with an author.

Ernestine Evans wrote to Editor Archibald Shepperson in 1940 that she “went off to New Hampshire for a weekend and have stayed forever,” as a way of explaining why her page proofs had been delayed. Shep, as he was known to her and other close associates, confided that he was “inclined to be jittery when things are late,” owing to his status as a “novice editor.”

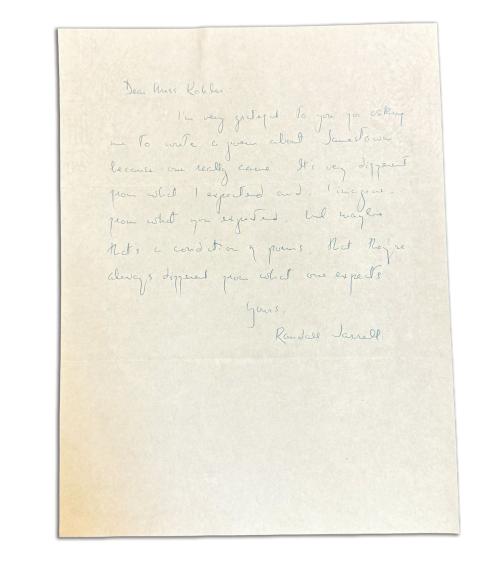

When Editor Charlotte Kohler solicited then–Consultant in Poetry Randall Jarrell to write a poem about Jamestown for the magazine’s Autumn 1957 issue commemorating the settlement, Jarrell claimed to “like the idea,” but he wasn’t sure if he could really do it. He told her he would “try to drive to it” to “see what it's like; perhaps seeing it will work.” The trip must have been successful. Jarrell wrote to Kohler: “I’m very grateful to you for asking me to write a poem about Jamestown, because one really came.”

Then, as now, solicitations could come from the other direction too. “Are you interested in a seventy-five-page novella, plus or minus 35,000 words in situ? Called Chicago? That takes place in 1959? With the Machine as its subject? And where the lady of the story, one Carole Nierendorf, comes from a tidewater town called Blackford, Virginia? My god, how can you resist?” This is from Ward Just to Staige Blackford, in what we’ve come to call the “chicken chasseur letters,” to distinguish it in the volumes of correspondence between the two. Over many years, Just and Blackford shared details of their lives, travels, gossip, comments on literature and culture, along with the business of writing and editing. In the summer of 1986, Just declines to review a book for VQR due to a conflict of interest—the author is “an old friend.” He shares with Blackford the anecdote that this author-friend of his is “the only man I know who hand carries Chicken Chasseur from the kitchens of the Century Club on 5th Avenue to his house in West Tisbury.”

In his response to Just, Blackford expresses admiration at this feat, then goes on to reject the novella on offer—what would ultimately become Jack Gance—for length. But he has some notes: “I must say that if you’re going to name a town in the Old Dominion Blackford, Virginia”—an obvious ode to Staige himself—“you could at least put it in the Piedmont and not in the Tidewater.” Many editors will admit that it’s easier to edit than it is to write. Perhaps Blackford agreed.

“Letters are the great fixative of experience,” Janet Malcolm wrote in The Silent Woman, her book about Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. “Time erodes feeling. Time creates indifference.” But, Malcolm reminds us, “Letters prove to us that we once cared.” Over a century, the VQR archives show just how much the editors and writers cared—about their reputations, and that of the magazine; about the state of the world; about money. Under the editorship of Lawrence Lee, Josephine W. Johnson responded to a query regarding the middle initial in her byline: Might the editors leave it out? “I have been signing all my work Josephine W. Johnson…in order not to be confused with Josephine Johnson of Norfolk, Virginia, who has appeared in many magazines….We are quite frequently confused, so I have tried to use the W as consistently as possible. I hope this will explain it to you too.” (TL;DR: No.)

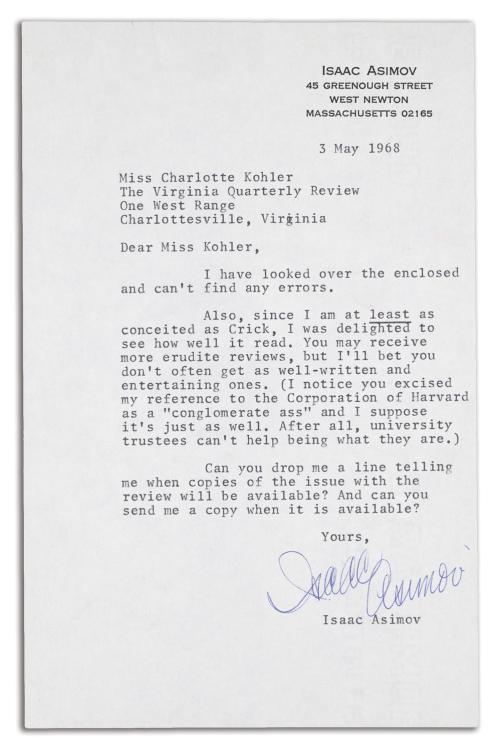

Isaac Asimov showed more self-confidence when he returned the proofs of his 1968 review of The Double Helix by James D. Watson. “I was delighted to see how well it read,” Asimov wrote to Editor Charlotte Kohler. “You may receive more erudite reviews, but I’ll bet you don’t often get as well-written and entertaining ones.” (Men, amirite?)

VQR editor Lawrence Lee solicited then-First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt for “an article on the more serious aspects of the liberal woman in the important activities throughout the world today.” Roosevelt forwarded the letter to her agent, George T. Bye, who conveyed that she was “pretty much tied up at the moment,” but that she did feel “so kindly disposed toward” VQR that she was willing to write something. That was in July of 1938. More letters followed. In late October of that year (on my birthday), Bye conveyed to Lee that Roosevelt was “horrified at the idea of doing thirty-five hundred words.” The horror! “A thousand words is about her limit,” the agent said, “but she is going to do her best.” Roosevelt’s “Keepers of Democracy” appeared in the Winter 1939 issue, coming in at just under 1,700 words.

The Nobel Prize–winning German novelist Thomas Mann found Shep’s March 1941 offer of publishing “a contribution in German…moving” and accepted “with particular pleasure.” Upon submission of “Denken und Leben,” Mann wrote Shep, “In these times where I have the obligation to give whatever little assistance I can to the many unfortunate victims of Nazism, demands on me are heavy.” A mere five years earlier, Mann’s German citizenship had been revoked, after which he emigrated to the US in 1938. Mann’s article confronted Nazism in Germany; VQR printed it in German without an English translation, thereby solidifying its internationalist-leaning position.

Lest we forget the transactional nature of the work, Mann also wrote of Shep’s “readiness to remunerate [his] work at a higher than your customary rate of five dollars a page,” saying he did not consider “a recompense of seventy-five dollars” to be “excessive.” Forty-five years later, Staige Blackford would write ICM agent Suzanne Gluck, “The kind of fee I can pay for Ann Beattie’s story ain’t in the same ballpark with The New Yorker. Our policy is to pay upon publication…and we pay by the printed page. In Ann’s case, however, I will probably make an exception and pay a flat fee of $500 or so.”

In response to a request for a contributor bio in 1950, the up-and-coming poet Adrienne Rich wrote, “My literary history is really very slight; I have been writing since I was very young, but this is my first appearance in any major publication.” We have no evidence that Rich corresponded about fees. We do know that the poet H. D. was paid “one hundred francs” for three poems in 1952. She lived in Lau-sanne, Switzerland, at the time. In today’s US dollars, that would be roughly $590, proving every writer’s point about rates having been static for decades. (VQR currently pays $200 per poem—guilty as charged.)

Southern writer Allen Tate had a longstanding relationship with VQR, publishing five poems and as many essays across forty-seven years but submitting dozens more. Tate’s personal correspondence begins with founding editor James Southall Wilson and continues through Stringfellow Barr, whom he addresses as “Winkie,” and ends with Kohler. Never one to mince words and seemingly baffled by the mounting rejections he faced, Tate shared his frustrations with Barr: “You have steadily rejected my best poems…only to print very second-rate work. Do you happen to know the Virginia Quarterly is famous for rotten poetry? Well, it is, and if you haven’t heard it before this, it’s because I’m the first person rude enough to tell you.” To Lambert Davis, Tate emphasized his “poverty” when writing of his “need of cash,” saying, “it would be damn nice of you if you could send me a check right away!”

Soon after his early publications in the magazine (“Idiot” and “Idyl”), Tate sent more work along with a brief accompanying note: “I herewith continue my bombardment.” Other writers submitted once, were rejected, and never submitted again. Sylvia Plath, for instance, whose poetry was “read with a great deal of interest” in mid-October 1958 but ultimately returned to her within two weeks because Kohler was unable to “find a place for them.” Having spent time in the archives, I recognize this as a form letter; having been on the receiving end of submissions for nearly fifteen years, I applaud the quick turnaround. See also: Rudyard Kipling.

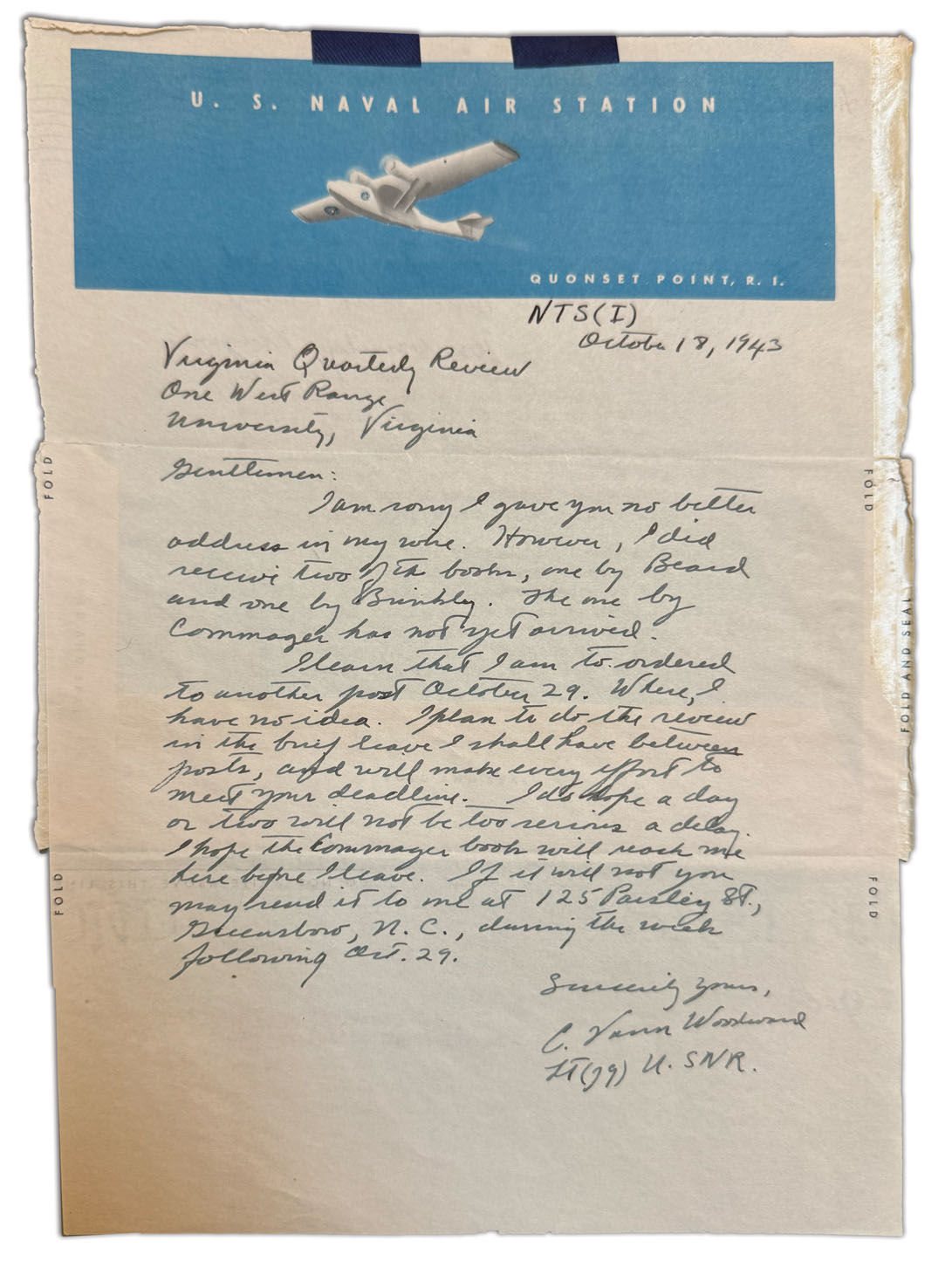

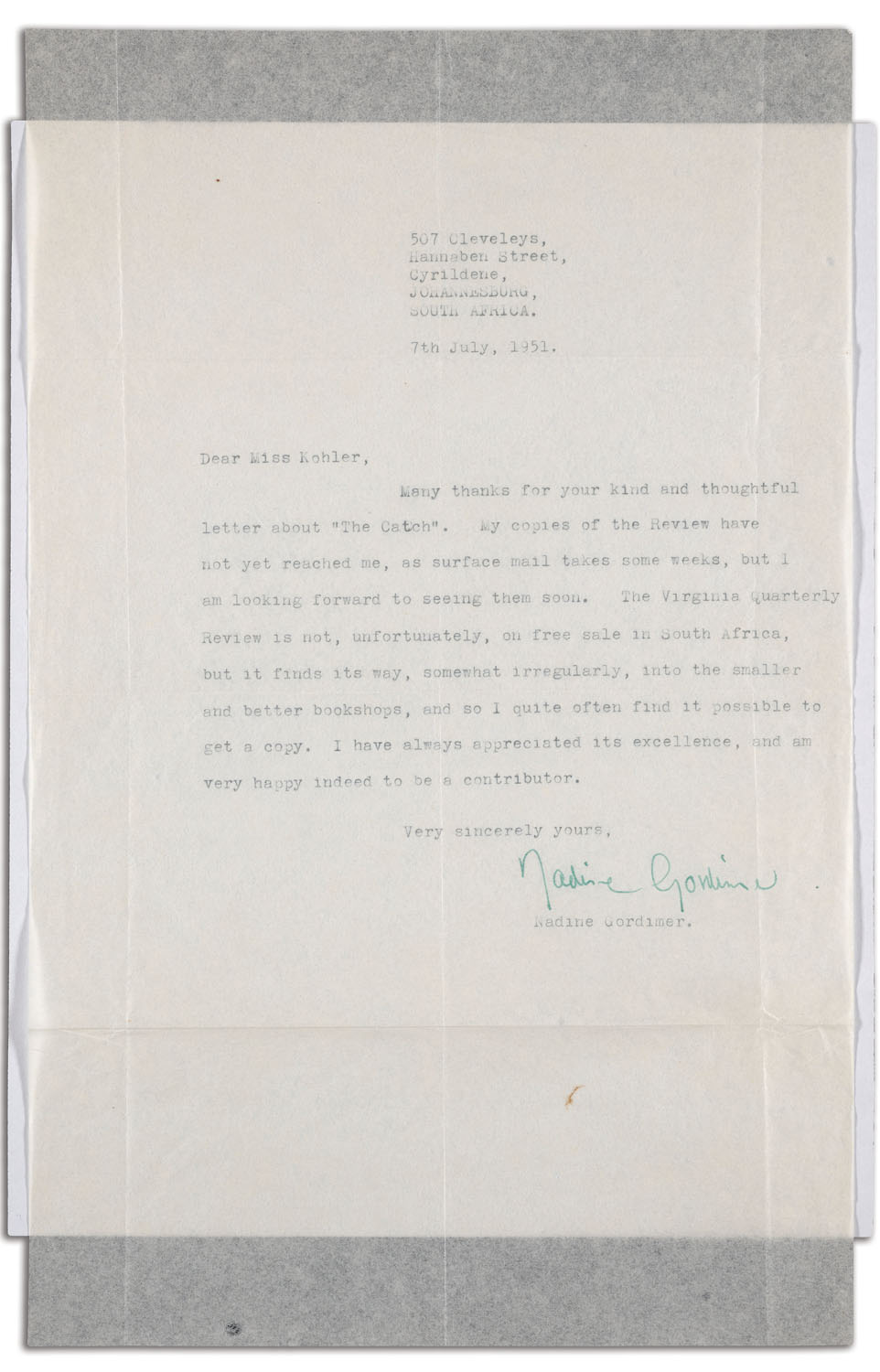

A century’s worth of archival material takes many forms: hastily dashed-off notes on onion skin paper; Western Union telegrams; dispatches on US Naval Air Station letterhead; typewritten letters from the Library of Congress. Photos. Postcards. Scrapbooks of press clippings from one hundred years ago. Proofs marked up in red or blue ink.

Someday, long after our tenure here, the archives will even hold a greeeting card and a jar of syrup. Upon publication of her story “Cold War, Hot Mess,” reporter Lois Parshley, who is based in Alaska, sent Editor Paul Reyes a note of thanks, along with a mason jar of homemade fireweed syrup. The story had been spiked by another publication but, after being published in VQR, went on to become a finalist for the National Magazine Award in Public Interest. In her note, Parshley points out that fire weed is Alaska’s unofficial state flower. “It’s resilient,” she wrote, “one of the first pioneers after a burn. You often see a carpet of shocking pink rising between blackened stumps, or poking out of cracks in concrete.” For the writer, the flower’s stubbornness pretty much summed up the dogged spirit of a publication so ardently dedicated to cultivating talent with the long game in mind. “I love the idea that, its tiny seeds can, against all odds, transform a landscape.”