Measures of Contact

1.

In 1907, Constantin Brancusi sculpted a kiss. The sculpture suspends questions of individual identity: To observe is to remain at the margins, to walk around a perimeter with no access to its interiority. There, at the limits of the face, only the edges of eyes and lips are visible. In 1926, Brancusi sculpted Bird in Space and shipped it to the US. But US Customs wouldn’t recognize it as art, since (they argued) it didn’t resemble a bird. So the artwork was taxed. A lawsuit followed. Brancusi v. United States (1928) updated what Customs considers art.

I too was curious about the limits of the face, the legal rationale of resemblance, and the objects that, like Brancusi’s work, cross the border separating art and law. Initially, I focused on the US government’s requirements for visa photos. The important part was “to interpret.” Interpretation resists regulation: Sanctions become possibilities. If (after David Graeber) bureaucracy allows for the suppression of interpretive labor, then engaging the bureaucracy of ID images interpretively produces documents too unsatisfactory for law, too derivative for art. But if used to navigate the relationship between art and law—to cross borders—they might be of value. I asked friends to model. A and A said yes.

Naturally, most visa-photo requirements concern the face. Forgoing the face means attending to technical specifications: in color, white or off-white background, evenly lit, sharp focus, the head constrained to fall within a narrow percentage range of the frame’s height, no shadows. Setting up the photo studio creates some historical resonances—these conditions are an interpretation of those defined in 1890 by Alphonse Bertillon, when he standardized the mug shot. He reminds us that the model’s “tranquility” is one of our concerns.

Some days after I presented the project, A and A asked me for the photos to include as evidence of their relationship for a green-card application to United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. I tried to imagine the Customs agents who, in 1913, processed Brancusi’s Kiss. What do they see?

2.

Part of my summer job’s hiring process required a fingerprint scan at an IdentoGo Center. Their fingerprint-based background checks run searches against FBI and state criminal databases to create a complete criminal profile.

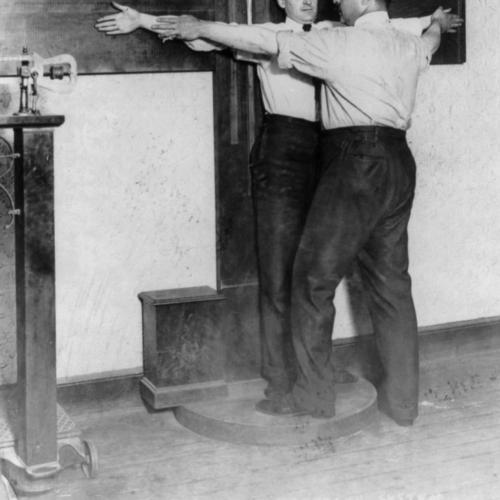

I arrived, waited. The employee called my name, asked for my ID, and entered its information with quick keystrokes. I input my Social Security number twice, less agile, afraid of a mistake. He stood up next to me. He was taller and his lips landed on my sightline. He put his hand on mine and began the digital fingerprinting process. He held my fingers one by one, guiding them into a slow rolling motion on the greasy glass surface. While the computer processed, his hand lingered, our fingers almost intertwined. I recalled the images police stations used to demonstrate how to take measurements of a criminal’s body that would be uniquely identifying. In one of those images, the hands of two anonymous officer-actors are tenderly palm in palm. In another, an officer spreads his arms while his partner measures the spread by opening his own arms, their bodies pressed together, their faces nearly touching. Once, I thought I read a nervous smile and imagined it as a poorly concealed desire. I wanted an image of them in the same embrace, eyes locked this time. After looking at my measurer in the eyes while he held my left hand with both of his, I realized IdentoGo’s security cameras were capturing a version of the image I had fantasized about.

Can desire defer measurement? If he kissed me, would the resulting images render my facial biometric information momentarily unavailable to IdentoGo’s surveillance systems?

Obviously, we didn’t kiss. He asked me to sit in front of a small off-white background, and then he made my image. Photography promised more than a wealth of detail, says Allan Sekula—it promised to reduce nature to a geometrical essence. The archive, then, could establish a standard measure for the criminal, locating each criminal body within a mapped collective.

On my way home, I listened to a guest on talk radio discuss the possibility of Palantir managing a centralized database of citizens.

3.

A label on the gallery wall next to a framed photograph of the couple kissing showed, with the abstraction of a map, that on the other side of the wall—behind the image—there was another image, its reverse. To get to the other side, you had to exit the building.

Someone said that it reminded them of COVID, of a kiss dangerously closing the limit separating two spaces that should remain distinct, bringing the outside in contact with the inside when, at the end of a workday, they kissed their partner. Another person said that the off-white background of the photographs matched that of the walls. It looks, they said, as if they had been photographed in the gallery. Would Alphonse Bertillon, who codified the mug shot, appreciate the diffusion of light here? Others wondered what truths or claims could be derived or refuted from these staged images. Can we know if they’re a couple? Can we know if the kiss is sincere? Can we attach to it words like genuine, real? Can we trust it?

We walk around the kiss with no access to its interiority. This time, however, walking around it means crossing walls. The questions inside the gallery, like the images, have their counterpart outside. Beyond these walls, immigration agents review portfolios containing photographs of couples. We can picture them asking: Can we know if they’re a couple? Can we know if the kiss is sincere? They want to determine, since there is a border to be crossed, whether these images depict something genuine, real, without intent to deceive. With metrical accuracy, they will reduce all sights to one standardized register. And if it’s deemed a ruse? Was it in the gallery or outside of it that someone pointed out that in Justinian’s Digest of Roman Law (6th century CE) there was a prohibition against acting, punished by civil death?

These agents—like Anne Carson would say of Audubon and his birds—understand light as an absence of darkness, truth as an absence of uncertainty However—to use words from Acie Clark, another poet—no amount of light makes a wall a window.