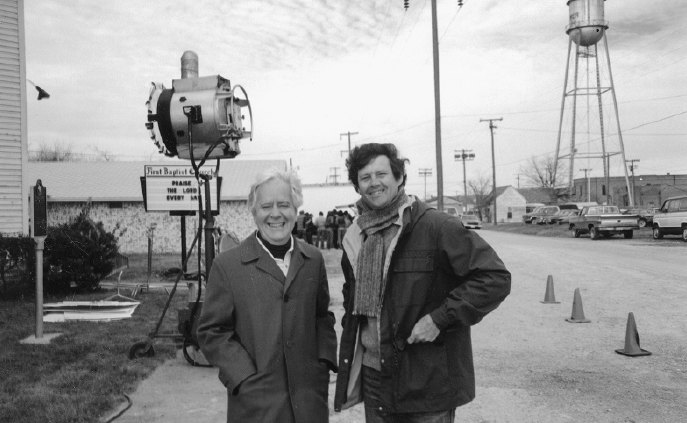

An Interview With Horton Foote

According to our research as the editors of The Voice of an American Playwright (2012), this is the first interview to explore more than Horton Foote’s writing and general biography. Conducted by Professor David L. Middleton at Trinity University, in San Antonio, in 1973, the interview’s academic environment made it appropriate to ask about such essential issues as the contexts (both physical and political) for Foote’s screenwriting, creative process, sense of place, and experiences in film and television production.

This insightful interview explores Foote’s work on To Kill a Mockingbird, The Chase, and Tomorrow (which he had just finished filming), as well as his unwillingness to compromise artistic integrity for commercial success. A few years later, Foote’s desire to maintain personal control of his films would lead him and his wife, Lillian, to create their own production company, which brought The Orphans’ Home cycle to the screen. His film work during the 1970s and 1980s (Tender Mercies, The Trip to Bountiful, Convicts, Courtship, On Valentine’s Day, 1918) would help diminish Hollywood’s stranglehold on cinema and give rise to an independent-film movement. His commitment not only inspired other filmmakers, but his character-based movies served as alternatives to the flash and fast-pace typical of Hollywood films.

Foote explains that getting “inside the structure” of work he adapts is the “essence” of the process, and he uses the metaphor of the composer to describe the role of the writer in film production. Insisting that he is “old fashioned” in being unwilling to write for audiences, he outlines how the politics of filmmaking can take the story from the writer’s hands (The Stalking Moon), how producers, exhibitors, and distributors shift the focus from the art of filmmaking (Tomorrow), and how in some cases timing can be everything (The Chase).

Born in 1916 in the small town of Wharton, in coastal southeast Texas, Foote studied acting in his late teens at Pasadena Playhouse in California and acted in his early twenties in New York before turning to writing as a member of the American Actors Company. In his six-decade career as a playwright and television and film screenwriter, Foote was honored with two Academy Awards, an Emmy, and the National Medal of the Arts by President Bill Clinton. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1995 for his play The Young Man from Atlanta, and was inducted into the Theatre Hall of Fame.

Throughout his long and distinguished career, Foote maintained strong connections to his rural roots in his story-driven plays about family. He adapted a number of works by Southern writers to the screen and television, including Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Flannery O’Connor’s The Displaced Person, and William Faulkner’s Barn Burning. His magnum opus, the nine-play cycle The Orphans’ Home, is a social and moral history based on the lives of his parents. In the estimation of New York Times drama critic Frank Rich, he was “a major American dramatist whose epic body of work recalls Chekhov in its quotidian comedy and heartbreak, and Faulkner in its ability to make his own corner of America stand for the whole.”

Through his words, that corner of America will be remembered and studied for a long time.

Middleton: Would you please describe your composing strategies when writing for film?

I’ve changed over a period of time. I used to love stenographers’ notebooks, but by the time it looked as though my family would have to leave the house, that was the end of that. Then I used big loose-leaf notebooks, and lately I’ve fallen in love with just stacks of loose-leaf paper. Why, I don’t know, except that I can destroy that very quickly if I don’t want to use them. I’m my own editor.

The paper I use is lined because I write very badly. Penmanship was never one of my accomplishments. I think I write in a kind of shorthand. I kind of make it fancy because I write so badly, so I try to make it interesting. It really is a problem to read my writing. I have a young lady near Boston who can read my personal “shorthand” and transcribes my writing.

I don’t smoke any longer. I used to figure I had to have three packs of cigarettes when I wrote and twelve pots of coffee. I’ve tried to give up coffee, but not too successfully. But I don’t smoke. And at times I love music, but only certain kinds of music. When I was a young writer (and now I can hardly believe this) I had to have the radio on all the time. So when my children say they have to have the television on to study, I don’t get too upset. There is something very comforting about just the sound.

As to where I work, well, I work at home, on the third floor of a big house, and I’m always at the end of a day saying, “My God, I’m not getting anything done.” Often I do build up steam, but that steam starts about 11:00 at night, which is not convenient when you have to get up early with children.

You might understand from this that in a way I welcome the breakup of the big studios, actually. I worked for two of them, Warner and MGM, and both times—well, I just can’t describe the oppressiveness of it. You had to be there at 9:00 (and they had ways of finding out if you weren’t there) and you literally punched the clock when you went in and punched the clock when you went out. You stayed until 5:00, and every day, at Warner’s, you sent in what you’d worked on that day.

Now, some writers can function within any system. Tennessee Williams, who’s a friend of mine, although I haven’t seen him for some time, worked at Metro, and I think he wrote The Glass Menagerie during that time. To me it was like the numbing atmosphere of a factory! Twenty writers would work on one story. It just has no meaning, and yet you have to say there was some interesting work done. Evidently [Bertolt] Brecht has to have almost a Hollywood atmosphere. He has to have collaborators, but they would drive me crazy. He needed that kind of stimulus. All I’m saying is that some systems are more difficult than others. Me—I need a lot of privacy and to be left alone a long time.

Working in a solitary way like that, isn’t it possible to become euphoric about a piece, to get whipped into a state during which one’s judgment isn’t as critical as it must be

That’s right, and that can fool you. You think, “Oh, it’s just marvelous, and there’s nothing going to stop me … ” and then … I’ve found that sober evaluation the next day is very valuable. I have this thing about putting drafts in a drawer. I think a drawer is very magical and sometimes there is no point in forcing it. I’m a great believer in the “refrigeration process.” Put it away and sometimes something happens to it; sometimes it sprouts, sometimes it diminishes. Often when you go back it’s amazing how much of the work is done for you if you don’t use your will too much. You see the creative process is a very delicate thing, and too often we try to will it. That’s why I don’t really like commercial setups too much. You’ve got to let your creativity find its own kind of speed.

In anticipation of the demands of film and television, is it beneficial to use as an “audience” someone whose opinion one respects, someone to present the text to, as a means of curbing the self-indulgence one tends to feel for one’s own work?

I used to do that. I used to have great rooms full of people I’d just love to read my plays to. I don’t do that anymore, and I don’t really know why. I think finally you have to be very careful, because I know more writers who have been injured by improper criticism. You know, a writer’s emotion is very delicate, and many writers expose themselves too early too soon to people who will look down at them. And you really have to finally stand on your own judgment.

Often writers associated with the South, such as Eudora Welty, for example, emphasize the absolute importance of “place.” Given the fundamental role played by geography in your own work, is living and writing in New Hampshire a help or a hindrance to a native of South Texas? To be perfectly candid, why have you made the decision to live so far away from that which is integral to the stories you create?

I’ve rationalized it. I don’t know whether it helps or hurts. I sometimes get very lonely, personally, for the South, and of course I’m here as much as I can be. James Joyce, you know, felt in exile, and he wrote minute letters to Ireland and hounded his family for details. But he felt that it gave him a certain kind of perspective, and that kind of exile does. It keeps you from being too absorbed by the specifics. Sometimes I get so hungry to get down to what I feel are the sources that I just want to take a plane and go. But then other times I do find that a critical kind of meditation takes place and something happens. The Southern writers that I have known best—well, the one I was closest to was Carson McCullers. We lived together in a little Hudson River town in New York. She was from Georgia, and very Southern, but she felt the need to be away from the South. It upset her.

We have a problem in America in that we don’t really know ourselves. I wouldn’t want to live in New York again or in Los Angeles, because I think that does get to be a very, very inbred atmosphere. Frankly, I’d never analyzed my processes until I began to think about Flannery O’Connor’s suggestion that the better fiction writers, even though they’re not good painters, like to paint because it’s all a projection, a visualization. I do know that my work comes out of a great deal of meditation, and I guess out of that thought comes a particularization of the visual and also of the technical aspects of the visual, if you know what I mean.

Audience: Since you have written successfully for a variety of media and have a substantial body of published material, would you be interested in rewriting and revising any of your earlier pieces?

I would indeed be intrigued to go back into work that I’ve finished and in most cases published, though I’d have to be very, very careful, because writers go through stages and periods and get funny ideas about the work. When you go back to it, it often strikes you as totally different. It is often much better than you thought it was and you can’t improve it.

I used to think that reworking was a bad idea, but men that I respect constantly rewrite, sometimes not to the advantage of the piece. Yet I do feel you grow tactically. See, I’m also trying to develop a lack of fear of silence. So many writers feel they have to write, and I don’t think that it’s a bad thing not to write for a while; and maybe that’s the time to go over things, just to force down that neurosis of having to do, to compete.

See, there’s a school of novelists, Norman Mailer and others … well … I was going to say Truman Capote, but he said he doesn’t need to compete because he’s better than the others, and William Styron. They’re always talking about “the champ,” and “the heavyweight,” and you know, it’s all so competitive. But which of them is like Ezra Pound? Which would take a year of his life and away from his work to give to the work of another man as he did for T. S. Eliot?

How does one prepare for the unique challenges of writing for theater, film, and television?

Formal education wasn’t much help in my writing career, for the simple reason I never went to college. I was thrown into theater as some people are taught to swim. I didn’t want to go to college because I was afraid I’d never get to the theater. When I was fifteen, I thought I wanted to be a great movie star by the time I was seventeen. If I wasn’t, I was a failure. Somehow, this gave me a source of energy and drive to stand up to my parents, and I went to a professional theater school [the Pasadena Playhouse and the Tamara Daykarhanova School]. So I’ve never learned anything about writing except in a very difficult, professional way. Most of my training as a writer came as an actor. I learned certain technical things about plays and about structure.

Would you describe in more detail how you “build a script” on the basis of other original material?

Actually I found that when I began to adapt things, they just assumed I knew how to do it. Well, I didn’t know how, but I’ve found I have a feeling for structure, and if one can get inside the structure of a given work and render that, that’s the essence of the work. But of course it’s important not to be afraid of the work, and that’s why I have a reluctance to take on what I consider very ‘important’ novels; if you tamper with the structure, then the whole thing goes.

There are certain novels that really should exist only as novels. I could name a few of them that I feel that strongly about: Madame Bovary, most of Willa Cather, Tender Is the Night. They are so structured as novels that the minute you start changing that, you lose the essence of it. Other novels have a looser form and you can actually do structural work. That’s really what I think is the business of the adapter: to rethink it structurally, to re-see it structurally in dramatic form.

Let’s use To Kill a Mockingbird as an instance of the problems and possibilities facing an adapter, then. Is it accurate to consider Harper Lee’s material as having been fundamentally changed into Horton Foote’s?

The studio asked Harper Lee to do the script, and she didn’t feel she knew enough about dramatic form. I was her choice, and I had a great deal of sympathy with the work. I had done only two adaptations before, so we had long talks and I said, “You know, there’s going to come a time when this has got to belong to me and I’ve got to take this over.” She was very supportive, and that’s what she wanted me to do. Well, I didn’t use it merely as a “departure” and write something entirely new, but I did write many scenes for the film that don’t exist in the novel. The whole time sequence had to be redone because the novel is sprawling in the sense that it goes over many years and we wanted to find a unity of time.

Obviously the problems one runs into in adapting a novel depend entirely on the novel and on the intent of the filmmaker. Some people buy novels and tell you, the writer, not to read it because they’re going to do it all differently. That, in the old days, meant one of two things: the director was very bad as a writer and could use the novel as his “homework,” or they were buying the title for what they called “box office insurance.”

If the intent is really to make something of the novel, then the problems are primarily technical. For instance, as I said, in Mockingbird we had a major problem with time. Though part of the charm of the novel is its kind of sprawling quality, we thought that would make a very poor film, and we wanted to compress it into a seasonal thing and to bring more sense of the unities to it. To solve those problems took two things: writing scenes that were not in the novel, and in a sense rethinking the whole structure of the work. We wanted to keep the action within this town—as you know, in the novel they go out of town—and within a year. That’s not exactly unity of time in a classical sense, but it’s closer than five years.

There’s a great cry that adapting novels into film ruins them, and of course sometimes it does. But you can ruin them as well if you’re too literal about them and do exactly what is there in fictional form.

And the other side of that coin. Can the adapter do too much to the original and harm it as well? If so, how have you learned to find that delicate point of balance?

Certainly you can do too much. It’s all too easy as an adapter to fall in love with your own effects. For instance, remember the old, mean lady the children were all afraid of? We had a whole section which was actually shot that had to do with her. But in the final structure of the film, it took us too far afield and we cut the entire thing—about twenty minutes. Also it’s possible for an adapter to alter a piece so much that the author would not recognize it as his own, the sort of thing that happened to me when Lillian Hellman worked on my novel of the play The Chase. She told people she was using it as a “departure,” and she did depart. Arthur Penn, a great friend of mine, was directing. They were in deep trouble with the work and called me. At that point, I tell you, I felt a little like Miriam, sister of Moses, who put the baby in the bulrushes at the edge of the stream and saw the Egyptians taking him. She went, then, and became the servant for Moses, but she couldn’t say she was blood kin. When I got the call I thought, “Well, maybe I can help, but it really isn’t mine any longer. I can be a servant in some way, but not the father of this work.” Later when I asked Arthur if he had read my novel, he said, “No, they told me not to.”

Would you describe the relationship between the writer and the many people other than the writer who are partially responsible for the process of creating film? Actors, for instance? They tend to be, at least in the eyes of many filmgoers, the most visible people in the industry and those who exert the most formative influences on the production. Do you take that kind of pressure into account and write a script with particular actors in mind?

I don’t really have any particular actor in mind while writing a script. In the case of Mockingbird, though, Gregory [Peck] co-owned the work. He owned The Stalking Moon as well. Now, it’s very difficult under those circumstances not to think of Gregory Peck, but I literally made myself not do it. I believe to do so is bad. Although some writers are very skillful at this kind of intentional writing, it would stymie me.

I am certainly willing, though, to grant the actor his creative territory. Acting is a creative process; so is directing. My instinct is to really want the actor and the director to re-see my work in terms of themselves because to me it’s like a score of music. I don’t want to have only one interpretation; I want Toscanini and Bruno Walters and Leonard Bernstein each to reimagine the material in their own ways. By insisting on that, I’m bound to get three different effects from the same piece.

This is where I disagree with Paddy [Chayefsky] a little. Paddy is a devil on the set. He wants very specific results; well, I don’t. I would love for twenty different actresses to do my parts, because I think you’d get twenty different interpretations. You see, I don’t think it’s possible to insist on a certain reading. If I were to direct my own plays for theater or television, I would direct them a particular way, but even at that, it would be only my interpretation. Now imagine working with Orson Welles. I would welcome such collaboration, even though I know I would have problems. But he would have problems with me too. I wouldn’t want him to interfere with what I feel is the writer’s prerogative. I feel I have my domain and he has his. Of course I wouldn’t want him to do to me what he does to Shakespeare sometimes, you know.

As a consequence of allowing that kind of creativity to others—or, more accurately, inviting it from them—what happens to the writer’s personal visualization of a story or place? Can the writer ultimately afford to care what the film looks like after being rendered visually by the director?

I do care and care deeply about the look of the final product that results from my writing. I guess in that sense, Tomorrow is my favorite because I had a very strong visual concept of it. And I did too of Mockingbird and of a film called Baby, the Rain Must Fall. The reason I felt very comfortable in Mockingbird was that I simply knew a Southern town in the 1930s. I just knew it. It may not have been Harper’s town, but it was my town.

You’d be surprised how little visual knowledge of America there is in Los Angeles or New York. Robert Mulligan and Alan Pakula, both of whom are sensitive men, just casually showed me first sketches of the house for the children. It was the biggest mansion you’ve ever seen, a cotton plantation. So I said, “Really, you know, this is not possible.” But I guess I had never described how the house would look and Harper didn’t either. I just assumed everybody knew what sort of house the Finches lived in. We finally found a good, usable house in Pasadena. That’s a wonderful story which shows how often things come together unexpectedly in a film to give the effect of truth. The novel was set in Maycomb [the fictional name for her hometown], but it was all gone by that time. Production people went to Alabama and were horrified to find everything had become supermarkets and filling stations. Then they found a little California cottage some freeway was going to overrun and moved it onto the lot at Universal, and it was precisely the kind of house the Finch children would have grown up in.

In the case of Baby, the Rain Must Fall, taken from a play of mine, and I did the screenplay too, unusual chemistry took place. It’s a different version of serendipitous chemistry at work. The film was directed by Mulligan, who loves my work, but visually he saw the South, or my part of Texas, very differently. Yet I was interested and I allowed him to do it because he picked out things you’d really have to go through Wharton County to find. He gave it a feeling of great bleakness, and actually my county is very lush.

But I’m willing to let it change, to take my chances if I’m in the hands of creative men. It’s when you’re in the hands of noncreative men that you’ve got to be in terror.

Coming back briefly to intended effects, how heavily can a working writer weigh audience reaction?

I never think about audiences. This is probably a lack in me. I mean, I really feel, and this is perhaps an old-fashioned point of view, I really feel you write for yourself. If you find certain satisfactions within yourself, that is finally what you are going to be left with.

Audience: How do you view the struggle to maintain artistic autonomy in the face of the material realities of production and distribution?

Have you ever seen the program that Lillian Gish does on college campuses? It’s really about D. W. Griffith, but she takes film clips from all the old films—remember she was truly a pioneer—and traces the development of silent pictures as she knew them.

Well, I remember about twenty years ago when she did a play of mine called The Trip to Bountiful, and she walked into our television studio with all her great energy, and she said, “You know, this can be the great American medium. It can be what movies began to be, but watch out. They’ll take it away from you.” And we just didn’t know what in the world she was talking about. “Unless you fight to control it, you’ll wake up one day and you’ll have no control whatever. They did it to the movies, and they’ll do it to this.” Her main point was that when big money gets involved in anything, and this is almost a cliché, in the arts in particular, usually it’s a corrupting influence.

One of the reasons we had a lot of freedom when I was just starting in television was that the sponsors weren’t putting much money into it. They didn’t think it had much potential, and as a result they didn’t pay much attention to it. They really didn’t look at scripts or care what went into content. But they do now.

Audience: If it would not open old wounds, would you tell us about particular battles and what you learned from them?

I’ll talk about the struggle over The Stalking Moon because it was a “friendly” war. Inadvertently I have been given credit for the film, but I didn’t write the screenplay. I withdrew from it. It’s a difficult novel, basically involving the conflict of two cultures. A white woman has been taken by the Apaches and has lived with the chief for a number of years and has a son, who at the time the film opens is about twelve. Anyway, he’s old enough to know his real father is an Indian. The mother wants to go back to what she calls civilization, so when the Army raids the village she returns with Gregory Peck, a scout, and subsequently goes with him to his ranch. The boy resents deeply leaving his father.

I did use this novel as a departure. The tragedy of the book, I felt, was the tragedy of the boy, who was forced to choose between cultures represented by two fathers. He’d gotten fond of Peck, a white man who had befriended his mother, but he adored his father, a primitive, punishing man. The Indian wanted his white wife and child back, and in the end he has a fight with Peck who kills him.

I just felt there was no way out of this but that the boy would be destroyed. The white man he respected killed the father he adored. What’s to be left for this boy? So the way I viewed the material, the boy was a victim of this culture clash. Today I think my point of view would be accepted, because I think we understand that there is enormous cultural conflict when two different civilizations collide. But they didn’t agree with this at all, so I withdrew. Although I certainly don’t consider them racist people, I think the film tended to be a racist film, because it’s slanted toward the white man and ignored the problems of the Indians.

But I lost that battle. I just took my name off the script. That’s how I had to personally fight the battle over what to me came down to integrity. There’s really nothing else you can do, because they control everything.

Audience: Apparently there was, then, no possibility of a happier compromise solution between you and those producing the film?

In truth, I never dealt with Gregory Peck about the film. I think if I had talked with him—well, you see, I was in a rather difficult position because the people were all friends of mine, and I didn’t want to hurt their project. I talked very openly to Mulligan and Pakula. Oh, it’s a complicated story. They both had three failures after Mockingbird, which was a great success. They were working with an old fashioned setup, National General, I think it was, which owned a chain of theaters. It was their first production and they were banking heavily on the European market and wanted to make an old-fashioned Western. I really didn’t serve them. I shouldn’t have taken the job. It just isn’t my kind of material.

What price does one pay, actually, for this sort of surrender?

Well, you should know that it takes more than the commitment to a moral issue to remove your name from a film. You renounce all rights to it forever. In other words, when a film of mine is shown on television, I get one percent of whatever the film was sold for. For Mockingbird, and for Baby, the Rain Must Fall—which I own the copyright to as well—it amounts to a nice little income. It means I can say “no” to some things I don’t want to do.

After withdrawing on principle from The Stalking Moon, how did you manage to accommodate yourself to Otto Preminger, notorious for his tyrannical methods and autocratic views, on Hurry Sundown?

Clearly that film might have caused the same problem all over again, but I had resolved it before beginning on the project. I wanted to be on the film for very specific purposes, because I never had worked with an old time filmmaker like Preminger. Well, I knew when I got into that that we wouldn’t agree. You go into a Preminger film knowing everything is going to be from his point of view.

Still, I respect him as a filmmaker. His work is high-powered stuff. I didn’t agree with the film, but I left my name on it because he personally asked me to do it and I felt in that case I knew what I was getting into and that I had no right to take my name off it.

So let’s say The Stalking Moon represents a loss, Hurry Sundown a kind of qualified draw. What conditions existed to make To Kill a Mockingbird such a comparatively satisfying victory?

One reason that film worked was that Mulligan was a very young director at the time and Gregory Peck supplied the muscle. He helped them fight so that they controlled the final cut. The studio would have panicked, I’m sure, over the film, but they didn’t ultimately get a chance to cut it or they would have ruined it. For instance, Sam Goldwyn loved the film but didn’t like the dialogue of the children and wanted it all dubbed because it wasn’t technically perfect. That would have spoiled it. Within the studio system, whoever controls the final cut controls the film; that really is the last battle. As a writer, therefore, what you want to do is to so excite the producer and the studio about the material that they will want to reinforce it, not destroy it.

Does the fact that it was independently produced account for your affection for Tomorrow. Does its history indicate a strategy you will use for working outside the system from now on?

First let me tell you a sad but revealing little story about handling the distribution of that film. I came to San Antonio with the film and went down to meet the gentleman who was the distributor. He said we had done very well in Tulsa, to which I replied, “Is that so? What do you mean?” And he said, “You had a very good gross. That’s why I brought the film here. I’ve not seen the film. I know nothing about it. I only look at the grosses. I hate films. I never see them. I only care about how much money they make.”

Well, of course, I find this just … insulting. I went home a saddened but a wiser man, realizing it isn’t just the big studios with whom we’re battling. The oppressiveness now is at the hands of the exhibitors and distributors.

Tomorrow probably wouldn’t have been seen at all except for the film festival at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. It was taken by a man named Kit Carson, who has pushed it so that it’s been shown at a number of college festivals. If it hadn’t been for those festivals, it never would have stood a chance.

Yet it was on the “Ten Best” list of all the New York film critics but one; Judith Crist said privately that it was the best film, in retrospect, of the year. Most Eastern critics picked it as the best film.

In addition, although Duvall was nominated as best actor in Tomorrow, as well as for supporting actor in The Godfather, the producers of my film—who didn’t have a lot of money—had to hire their own theater and advertise it for the Academy members to come and see it. I think about six showed up.

In the case of this film, which is an extremely important instance, I took very little money because I’m trying to establish the precedent of the writer controlling the copyright. I own the copyright of Tomorrow. In ten years all rights revert to me. But with most films, the writer owns nothing. The minute you write, it is in their domain. The only lever you have is the moral one; you can take your name off the film.

Since you were an established author with proven ability to reconfigure both fiction and drama for the movies, why weren’t you given the chance to work on The Chase when that was made into a film? Was that by choice or a fact imposed by the system again?

All right, let me tell you the parable of The Chase, for although it’s a rather long and difficult story, maybe you can see how things do and don’t get done in this crazy world of film writing.

Mildred Dunnock had heard about it, and we were old friends. She wanted to play the mother. Karl Malden had sent it to her, and at that time he wanted to play the sheriff. They couldn’t get the production. Mildred was a friend of Pat Neal, who at that time was having a very close relationship with Gary Cooper. When Pat read it, she said it was a fantastic part for Cooper. So Celeste Holm heard about this and said she’d like to produce it as a play with the Theatre Guild and Cooper in the lead. Cooper, however, when he came to town, asked to buy it for a film, to which I said, “Well … ” and he said, “You know, I’m a very nervous man. I vomit after every take and would go crazy if I had to be on stage. I was on stage once at the Paramount Theater in a personal appearance, and I had a breakdown. I can’t do it.” I was much younger, and just looked at him and agreed he couldn’t.

Well, about six months later, I got a telegram from a lawyer, Arnold Weissberger, who was working for me, saying Gary Cooper has made High Noon and it’s stolen from your play. I recall thinking, “Oh, marvelous. We can sue him and get a lot of scandal.” But when I went to see High Noon, I could honestly say it had nothing to do with my play. If this is what they think my play is about, I’m in deep trouble. It’s about a sheriff, all right, but has nothing to do with my play, so I wouldn’t sue.

Then a producer named Jean Dalrymple had the play and the only really ugly thing I feel I’ve done in the theater occurred, and I’m very ashamed of myself. Jean got it for Franchot Tone, a great actor whom I adored, but he was married to Barbara Payton, or some other young lady at the time, and though he wanted to do it, he also wanted her to be in the thing.

Meantime, José Ferrer was touching everything, and whatever he touched was working. I got a call at 11:00 at night. He had just found the play. He said, “Get right down here”—he was playing in The Shrike—and it was all very dramatic. But although he wanted to do the play, he didn’t want to use Franchot. The upshot was that although I was supposed to meet with Dalrymple the next day, my agent told me not to answer the phone, and I never did. I just took the play away from her and gave it to Ferrer. Franchot and I later became close friends and he forgave me, but I felt quite shabby.

So Ferrer took it. Remember he was the great actor-producer-director, and the first thing he did was ask for coauthorship, to which I said, “Oh, no, I’m not going to do that.” This was the old practice in the days of strong producers. They would not get line credit, but they would get forty percent of what you made. He insisted he was very good on script, and I said I was delighted to hear that. And he told me he was like a coach, that on Stalag 17 he had come back between the acts and given the cast pep talks and it worked miracles. Anyway, he had a contract ready, and my agent was very eager. Ferrer said that I could stage the play and he would come in and get us really working.

Since I had never been on Broadway, I thought I’ll just make this trip. I got John Hodiak, who had never acted, and began to direct. The one thing we had in it was a girl named Kim Stanley whom my wife had seen off Broadway. We’d fought like tigers to get her in it, and I knew we had something great there. Anyway, we got bad notices in Philadelphia, and we began to rip the play, rip the play, change, change, change. So what we finally saw was not my play.

Hodiac didn’t know how to act, but there was an assistant stage manager in the play named Jason Robards, understudying Hodiac. He adored the work.

Finally about two years later, my agent said, “Let’s do it as a novel,” and that’s why I wrote it in fiction. It was well received, well reviewed, and Sam Spiegel bought it. The day he bought it, Jason called me and wanted to revive it off Broadway, but the die was cast. So the play really has never been done.

This is the old kind of Broadway story, but now that Broadway doesn’t make much money, playwrights have a better chance to stick with their material. For what it’s worth, that’s how you get into different mediums. If the creative life of The Chase had evolved differently, I probably would be writing only plays.

Despite having grown disillusioned when live television gave way to videotape, would you consider coming back to television if it were possible to do exactly what you wanted?

I don’t believe so. There just isn’t the possibility of being that free. We had the leisure and the great gift, when I worked in television to be able to fail. At that time, if we failed, Fred Coe would say, “Pappy, if you fail it doesn’t really matter.” He was from Mississippi and used to call everybody “Pappy.” That was not true, completely. You failed twice and Fred found a way to get rid of you. But there wasn’t actually the terrible disgrace—you were welcome to experiment. Let’s see, what did a show cost—$100,000? Now they cost $2-3 million. When I worked in New York there were these dictums from producers saying, “One set, few actors. Keep the cost down.” You know when my first play was done, it ran for $12,000. When my last one was done … well, right now it would be $300,000. So you can tell you’re right back to dollars and cents again.

If the bottom line is what a discussion of screenwriting often comes down to, it must be difficult for hopeful writers to accept.

Though I feel you write ultimately for yourself, many people of great integrity don’t agree. I’ve heard Truman say he couldn’t write if he didn’t know he was going to be paid for it. And some people have the ability to do things for money and then go on to do something else. That’s Gore Vidal’s point of view. Although you rarely see Gore’s name on Hollywood films, he’s done a lot of them, and he gets replaced on most of them. He feels it is all hackwork, that it’s all ridiculous. He really is a man of letters, in the old-fashioned, Victorian sense. He writes two or three hours a day, is extremely disciplined, lectures a lot, writes articles, and also fiction under another name, doesn’t he.

It’s all a great mystery to me how a writer can handle both commercial projects and those terribly meaningful to himself. I have been advised by the Screen Actors Guild and the president of it, that if I continued to work in Hollywood, I should have two names: one for the things I didn’t care about, and one for myself.