Take a deep right, Larry Griggs says, and we do, driving slowly into Baptist Town, a longtime African-American neighborhood in Greenwood, Mississippi, dating from the 1800s. I’ve never heard that term before but know exactly what he means—not least of which because I am here on the hunt of a deeper right, tracing the poles of a story involving food and civil rights that took place in Greenwood. One of the homes of the blues and the county seat, Greenwood sits some ten miles from where white racists killed Emmett Till in 1955, and less than 100 miles from where civil-rights workers Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney were murdered in 1964. Today, despite the changes in the Delta and in our country, the town is still divided by railroad tracks and history, with a stark, visible difference in its sides.

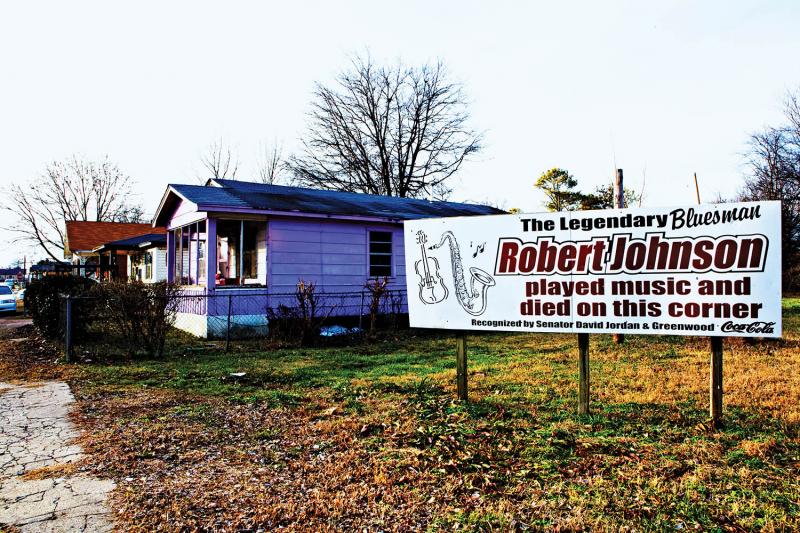

In its few blocks, Baptist Town holds a million visions: a bright blue “Old School Snowballs” truck with flat tires; a Camaro on blocks but with a new license plate; a billboard at the corner where blues legend Robert Johnson died, reportedly from poison, in one of Greenwood’s juke joints. (His grave outside Greenwood is a far more dubious affair.) A Mississippi Blues Commission marker indicates Baptist Town is “known for its strong sense of community” and “anchored by the McKinney Chapel M.B. Church and a former cotton compress.”

Nearby in the adjoining McLaurin neighborhood is the home of an unlikely yet increasingly recognized civil-rights figure, Booker Wright. The area bears two other anchors: Booker’s Place, the bar Wright owned, and Lusco’s, the upscale restaurant where he worked. Though just across the “wrong” side of the tracks, Lusco’s was already a Greenwood institution by the time Wright served there as a waiter. As my daddy used to say, there is nothing inherently demeaning about being a waiter—it demands great skill and little shame. Many a black waiter at a fancy establishment would earn the money that sent a child to college or to a better economic status; like Pullman porters, the role of waiter at an expensive establishment regularly commanded respect within the African-American community.

But serving as a waiter in Jim Crow Mississippi also required daily humiliations for black waitstaff meant to be invisible and unheard in a “whites-only” dining room. Wright testified to both opportunity and oppression for the NBC documentary Mississippi: A Self-Portrait when he said he wanted better for his children—“that’s what I’m struggling for.” After being shown behind the famed bar in his own place (depicted in several of the photographs that follow), Wright spoke straight to the camera about the double standards and racism of Greenwood’s white patrons, many of whom were also featured in the show that aired in 1966. After performing the delicious-sounding menu onscreen, Wright didn’t just speak about, but as, his customers, who must have thought him a good sport until that moment, reenacting their demand to smile even when being called a racial epithet:

Some people nice, some not.…What’s wrong with you, why you not smiling? Go over & get me so & so and so & so.…And I keep that smile. Always learn to smile. The meaner the man be, the more you smile. Although you’re crying on the inside. Or you’re wondering what else can I do. Sometime he’ll tip you, sometime he’ll say, I’m not going to tip that nigger, he don’t look for no tip. Yessir, thank you. What’d you say?…Yes sir, boss, I’m your nigger.…

So that’s what you got to go through with—but remember you got to keep that smile.

Wright’s words are haunting even today, reenacting not just racism but racism’s necessitated response. In 1966 they inflamed the closed society of whites in the Delta, many of whom frequented Lusco’s—and who were members of the local White Citizens Council, groups founded to oppose the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education’s desegregation ruling.

What’s more, Wright directly contradicted the words of such members shown in the montage before his scene—including the mayor as well as the lawyer for Byron De La Beckwith. Then living in Greenwood, Beckwith was twice tried but not yet convicted of the assassination of Medgar Evers. In the words of the documentary, this august panel “voices the orthodox liturgy”: “The colored people are very happy, extremely happy in Mississippi.” Another chimes in, “That’s a fact. Do you know anybody that disagrees with that?” There is only one answer—one right behind the counter at Booker’s Place, speaking on behalf of many others who could not gain access to the camera. What Wright said in just over two minutes offered a direct affront to the very system the well-to-do white customers of Lusco’s worked to maintain.

After the film aired, apparently with Lusco’s staff watching, Wright was let go from the restaurant. (Some maintain he quit, as if that makes a difference.) He was soon pistol-whipped—by a local police officer, no less—and was sent to the hospital, his own establishment firebombed. Both the man and bar survived. Years later, Wright was shot and killed by a bar patron; as described in the 2012 documentary Booker’s Place, his descendants and others in the community have suggested the shooting had a political motivation.

The following sequence of poems, Repast, honors Wright’s legacy. The title refers to the traditional African-American meal following a funeral. Whether formal or for family members only, held at a house of worship or the home of the deceased, catered by a favorite local spot or a community potluck, the repast is a ritual connected to other foodways, as well as traditions both African and American, Christian and more broadly religious. Where the wake before the funeral is primarily about the dead, the repast nurtures the living who share food and memories. The very word has come to suggest a reflection, not on the past but the future, a final supper after the burial that leaves the circle unbroken.

Wright himself has left a wide wake. These poems are some of the ripples from his defiant act, forming the better part of an oratorio—or musical setting for voice—I was commissioned to write by the Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA) for performance in October 2014. In the libretto, I wish not merely to quote Wright or speak for him—he well can speak for himself—but to sound out an inner life in which Wright, through quotation and the imagination, tells us what it means to wait. I even pictured a bit of staging: Over the course of Repast, his waiter’s serving napkin goes from bar towel to preacher’s handkerchief, as Wright literally transforms from a waiter to a barkeep to an activist—which may prove the same thing.

The music I imagined for the piece was black music from the last century, which still swings: blues (and rhythm and blues) overtones to those of gospel and soul music more generally. There is also church music, with the opening hymn intoning, Let us break bread together on our knees, since these poems represent a communion offering of sorts. I was fortunate to first hear the setting by composer Nolan Gasser at the same time everyone else did; to experience it as performed at the SFA Symposium by artistic director Bruce Leving-ston (piano) and singer Justin Hopkins (bass-baritone) alongside Wright’s granddaughter Yvette Johnson was to conjure up more than Wright, but a sense of a movement—one made up of daily insurrections, of giving voice and not giving up.

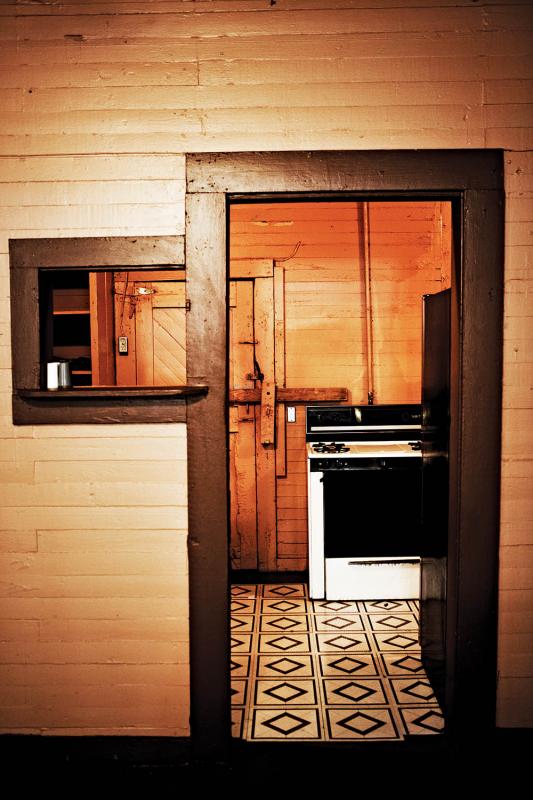

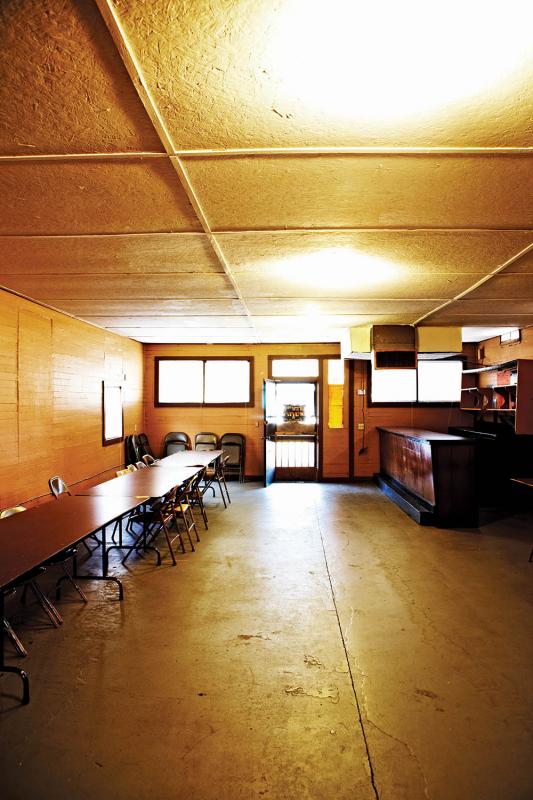

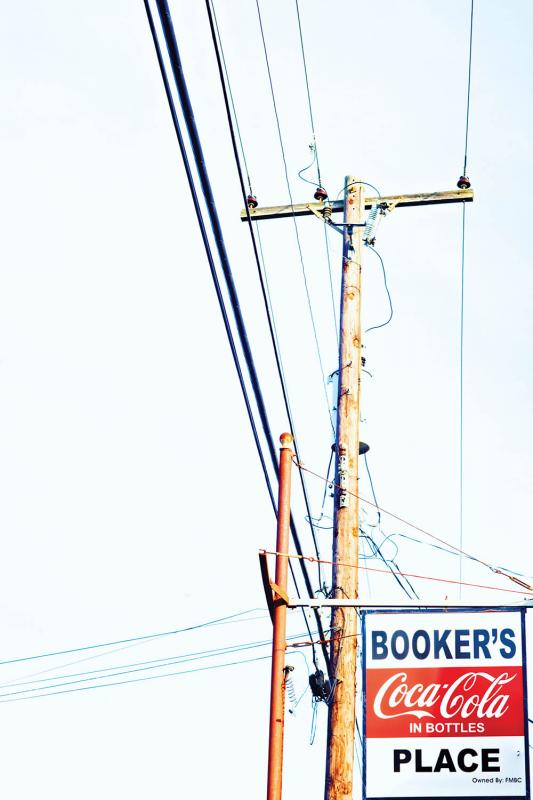

Some of Greenwood’s memory is held by Larry Griggs, who helps maintain Booker’s Place on behalf of his Friendship Missionary Baptist Church congregation next door, which now owns the property. (A photograph of him at Booker’s front door graces the start of this essay.) As in African-American music, the club and the church sit side by side—we joke together that some folks would go straight from one to the other. The area around McLaurin Street used to have many juke joints, whose lively nightlife often proved troubled. Over the past two decades, Friendship Church has steadily bought up and torn down more than a dozen surrounding establishments—leaving standing Booker’s Place, which maintains a place of honor in the community. Friendship Church has repainted and refurbished the space, using it for certain events—but kept his famous long bar. Several original Booker’s signs are kept, if broken, out back—this is no museum, only memory.

Having initially visited Greenwood in the course of writing the oratorio, I returned there for VQR in January 2015 with photographer Melanie Dunea. Melanie and I had been hoping to collaborate since we met several years ago, and this seemed a chance to expand the oratorio into the visual realm. How to conjure Southern life and not just its history—one not only complicated, and at times troubled for even those who experienced it, but one that’s been overdetermined by images of the sharecropper, dust, front porches, and cotton? How to go past a Mississippi only of the mind?

I have always conceived this project as the first of a series of unlikely but necessary civil-rights sites as viewed in poem and picture, one informing the other. In the photo-poem that follows, you will find Lusco’s and Booker’s Place, both of which still stand. Lusco’s continues to serve in its private, curtained booths, begun as a Prohibition necessity and maintained today. (Such booths are particularly popular in Greenwood and grace even newer bars.) Its elegance is my favorite kind—fading, along with the memory of desegregation. If you go, order the spicy shrimp.

Before Mr. Griggs takes us through Baptist Town, just north of Lusco’s, we drive around the corner from McLaurin to the adjoining park where Stokely Carmichael popularized the term “Black Power” in a famous speech, its history told by a further marker. Its cry seems not just a slogan, but yet another necessity denied in these parts. We circle back to take a picture of Lusco’s lush neon sign, with Coke on it; a man in the empty lot next door is grilling something on an open flame that doesn’t quite smell like meat. I only notice another, faded sign, high above, later—Coca-Cola, the Dark Lady of the sonnet of the South, which also adorns the new, spiffier sign for Booker’s Place.

Repast ends with “Sundaying,” a poem that pictures a redemption through food but also what my childhood congregation would call fellowship—a feeling of fullness, here through witnessing and driving over the waking world itself. As the singer announces before the final poem and song, Those who are able, please rise.

Hospitality Blues

Welcome. Have a seat—

I insist. I’m your host.

Your money is no

good here, no good

here no good

no good

no good.

Your money is no good.

Here. Your money

is no god here no—Glad

to see you all. We don’t

have a written menu

I’ll be glad to tell you

what we’re going to serve

tonight tonight tonight

We have fresh shrimp

cocktails Lusco shrimp

fresh oysters on the half shell

baked oysters oysters

Rockefeller oysters almondine

stewed oysters fried oysters

Spanish mackerel broil whetstone

sirloin steak club steak T-bone

steak porterhouse steak ribeye

steak Lusco special steak mushrooms

flavor of garlic Italian spaghetti

& meatballs softshell crab

French fried onions golden

brown donut style

Best food in the world

the world the world

the world is served at Lusco’s

He nods & rocks

Tell my people what you got.

The Maître D’s Lament

The hardest thing is knowing

when you’re free. Easy

to see when you’re not—

when the wind don’t

make a dent in how the fig

falls from the tree, or your

mouth never fed enough—

or your child-

ren, how much

to tell them? The meaner

the man be, the more

you smile.

When do you talk

about it, the men—

never one—who come

for you, burning

& cutting & crossing—

even a pistol

can be made a whip—

just for you saying

what’s true. Not

what you’re taught.

That’s a good nigger.

That’s my

nigger. Brush your

taut dark hair.

Reservations

Some call me Booker,

some call me John, some

call me Jim, some call me—

This is my place

I say, meaning where

I work but more

the green bar I tend

& keep, the mouths I feed

not only my children,

who I want better for

than me—the slenderest

tall trees. The willows

who weep. What should

my place be? It is loudest

here after the black descends,

gathers in the Mississippi

leaves, first green then

dark like me—my first

name’s Mack but nobody

calls me that. I’m named

for a man who made

his name at Tuskegee

which ain’t that

far from here

I hear.

Booker’s Place

It’s the haze that hurts.

Sometimes far worse

than when the sun

spits its rays

all over your face—

them days you brown

& redden, the work

can be like

to kill you—

so a man need

a place to go inside

his head & walk around

& rest. There’s a juke

joint of the soul, somewhere

you can have yourself

something cold, or brown

burning water—we used

to get ice in fresh, cut

from giant blocks,

sawdust, clean glasses

& good good food. I kept

the bar sparkling, shiny

as the teeth of the couples

on calendars behind me

staring into each other’s eyes.

Budweiser in cans, Nehi,

Drink Coca-Cola

Bottled up. This was my place—

a green room, a somewhere

you could twist, maybe spin

a partner on the dance floor

or just set a spell

& tap your foot, mine,

taking it all in.

We never let anyone

carry on too long

& made sure they carried

themselves home safe

beside the tracks

that also kept

their crosses, clanging—

that train red,

an eye,

then blue, bearing

down on you.

Death’s Dictionary

A shack made of ribs.

A house made of out.

A car made of rust.

A smile made of doubt.

A house made of fire.

A magician’s gesture.

Of cards. Of the Lord.

As preacher, pats his brow.

A joint made of juke.

A twist. A night away.

A wood made of green.

Of blood.

The kerchief now a bandage.

A place in the sun.

A home made of railroad.

A shack of shotgun.

Waiting

So this is what I said:

Now that’s what my customers—

I say my customers—

be expecting of me. Booker,

Tell my people what you got.

Some people nice,

some people not.

What’s wrong with you

why you not smiling?

Go over & get me

so & so and so & so.

And I keep that smile.

Always learn to smile

Although you’re crying

on the inside.

Sometime he’ll tip you

Sometime he’ll say,

I’m not going to tip

that nigger, he don’t look

for no tip. Yessir,

thank you.

What’d you say?

Yes sir, boss,

I’m your nigger.

But remember

you got to keep that smile.

Night after night

I lay down & I dream

about what I had

to go through with.

That’s what I’m struggling for.

I’m trying to make

a living.

For this they whipped

me good, but not dead.

A Glossary of Uppity

For please, please read

forget you.

For sun,

read none.

For love, read

money.

For money, read.

For smile, read

Bless Your Heart.

For uppity

read siddity.

For siddity,

read dicty.

For dicty, hincty.

For pleasure.

For unknowing.

For forgetting

read mystery.

For smile

read speak.

For hush

read shush

read shut up

read don’t

you dare.

For dare, read sure.

For speak up

read speak out.

For the future

say now.

For my children.

For ever.

Thy trumpet

tongue.

Thy work

never done.

For Thee,

read We.

Sundaying

And everyone working

the drive-thru is beautiful

smiling just

like the commercial

Thanks, I will

have a good day

& a double

cheeseburger too

And without complaint

the birds wake

you early

sun against the skin

Somewhere smell

of a grill

Cut grass & gasoline

And the church lady

her hat a bouquet

saying Hello

Hello

The sun a giant melon

And we’re not getting

any younger

but today no older neither

And why not

live forever

Why not wait

till tomorrow

to pay the phone

the gas electric

Why not pray

for a tie

instead of a win

for the game to go

long, on & on,

a million innings