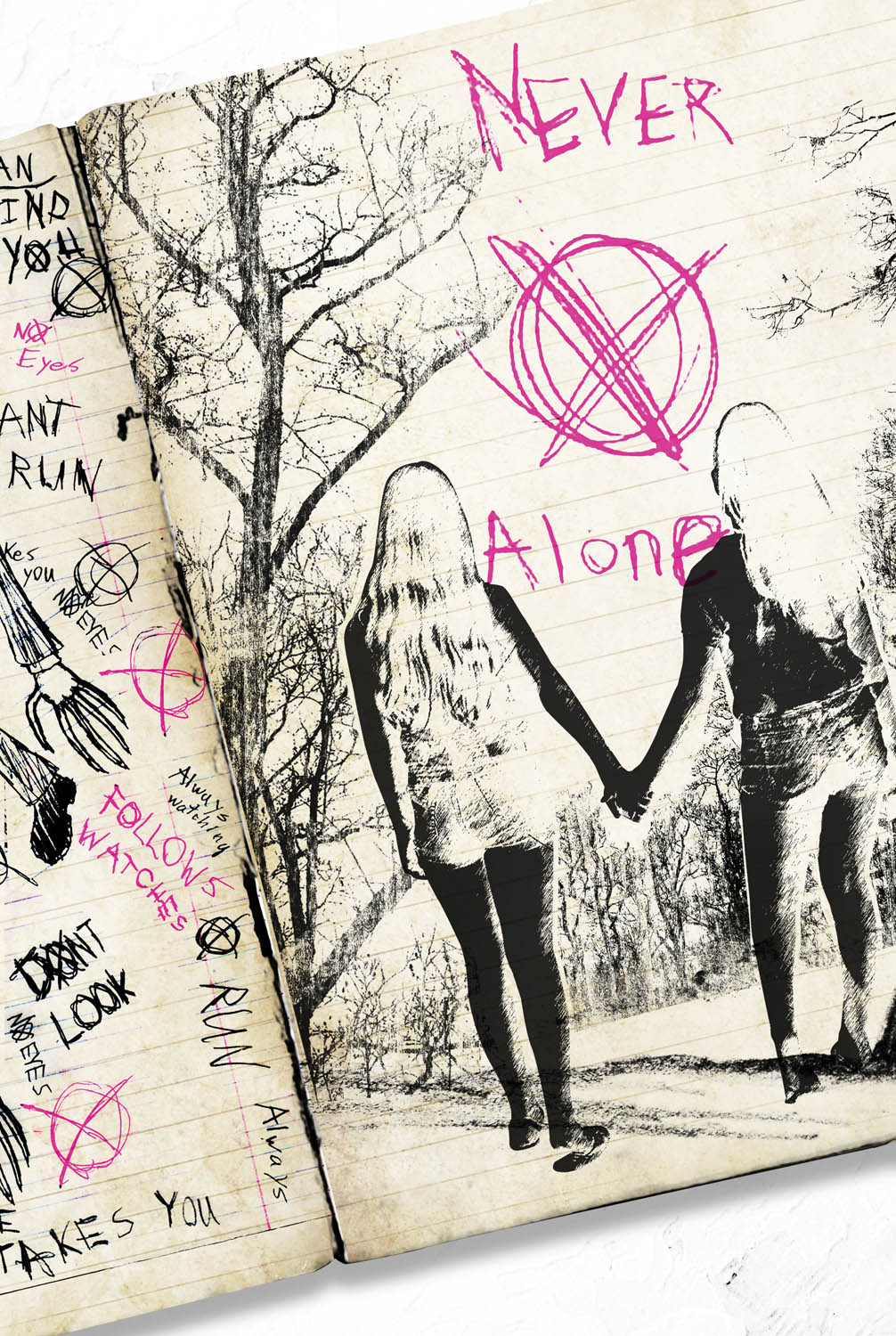

Here is an image, picked from the notebooks of an eleven-year-old girl in a suburb of Milwaukee, Wisconsin: a head portrait, in pencil, of a man in a dark suit and tie. His long neck is white, and so is his face—bald and whited-out, with hollows where his eyes should be.

Here is another: an androgynous kid (a girl, like the artist?) in a sweatshirt and flared jeans leaping across the page. She has huge, glassy black eyes and dark, stringy hair; she reaches out with one hand and brandishes a dagger in the other. Filling the page around her, tiny rainbows and clouds and stars and hearts—all the signatures of the little girl the artist recently was—burst in a fireworks display.

There are cryptic messages, too: a page covered in Xs; another inscribed he still sees you. These notebooks are charged with the childlike paranoia of sleepovers after bingeing on horror movies, of Ouija boards and Light as a feather, stiff as a board…

What is occult is synonymous with what is hidden, orphic, veiled—but girls are familiar with that realm. We have the instinct. Girls create their own occult language; it may be one of the first signs of adolescence. This is a language of fantasy, of the desire for things we can’t yet have (we’re too young), of forces we can’t control (loneliness, an unrequited crush, the actions of our family). This invention of a private language, both visual and verbal, shared with only a chosen few, gives shape to our first allegiances; it grants entry into a universe with its own rationale—the warped rationale of fairy tales. Its rules do not bleed over into the realm of the mundane, of parents and teachers and adult consequences.

But in May 2014, the occult universe of two young girls did spill over into the real. And within days of her twelfth birthday, all of Morgan Geyser’s drawings and scribblings—evidence of the world she had built with her new best friend—were confiscated. More than three years later, they are counted among the state’s exhibits in a case of first-degree intentional homicide.

On a Friday night in late spring of 2014, in the small, drab city of Waukesha, Wisconsin, a trio of sixth-grade girls gets together to celebrate Morgan’s birthday. They skate for hours under the disco lights at the roller rink: tame, mousy-haired Bella Leutner; Anissa Weier, with her shaggy brown mop top; and Morgan, the “best friend” they have in common, with her moon of a face, big glasses, and long blond hair. They are three not-so-popular girls at Horning Middle School, a little more childish than the others, a little more obsessed with fantasy and video games and making up scary stories. Morgan casts herself as a creative weirdo, and she relates to her new friend Anissa on this level, through science fiction—Anissa, who has almost no other friends and who moved down the block after her parents’ recent divorce. When they get back to the birthday girl’s house, they greet the cats, play games on their tablets, then head to Morgan’s bedroom, where they finally fall asleep, all three together in a puppy pile in the twin-size loft bed.

In the morning, the girls make a game out of hurling clumps of Silly Putty up at the ceiling. They role-play for a while—as the android from Star Trek and a troll and a princess—then eat a breakfast of donuts and strawberries. Morgan gets her mother’s permission to walk to the small park nearby.

As they head to the playground, Bella in the lead, Morgan lifts her plaid jacket to show Anissa what she has tucked into her waistband: a steak knife from the kitchen. Anissa is not surprised; they have talked about this moment for months.

After some time on the swings, Anissa suggests they play hide-and-seek in the suburban woods at the park’s edge. There, just a few feet beyond the tree line, Morgan, on Anissa’s cue, stabs Bella in the chest.

Then she stabs her again, and again, and again—in her arms, in her leg, near her heart. By the time Morgan stops, she has stabbed her nineteen times.

Bella, screaming, rises up—but she can’t walk straight. Anissa braces her by the arm (both of them are small) and she and Morgan lead her deeper into the trees, farther away from the trail. They order Bella to lie down on the ground; they claim they will go get help. Lying on the dirt and leaves, the back of her shirt growing damp with blood, slowly bleeding out in the woods, Bella is left to die.

About five hours later and a few miles away, while resting in the grass alongside Interstate 94, Morgan and Anissa are picked up by a pair of sheriff’s deputies. The deputies approach them carefully, aware that they are possible suspects in a stabbing but confused by their age. One of the men notices blood on Morgan’s clothes as he handcuffs her. When he asks if she’s been injured, she says no.

“Then where did the blood come from?”

“I was forced to stab my best friend.”

Morgan and Anissa do not yet know that Bella, against all odds, has survived. After their arrests, over the course of nearly nine combined hours of interviews, they claim that they were compelled to kill her by a monster they had encountered online. When discovered, the girls were making their way to him, heading to Wisconsin’s Nicolet National Forest on foot, nearly 200 miles north. They were convinced that, once there, if they pushed farther and farther into the nearly 700,000-acre forest, they would find the mansion in which their monster dwells and he would welcome them.

Morgan and Anissa packed for the trip—granola bars, water bottles, photos by which to remember their families. (As Anissa tells a detective, “We were probably going to be spending the rest of our lives there.”) Though they were both a very young, Midwestern twelve, they had been chosen for a dark and unique destiny which none of their junior-high classmates could possibly understand, drawn into the forest in the service of a force much greater and more mysterious than anything in their suburban-American lives. What drew them out there has a name: Slender Man, faceless and pale and impossibly tall. His symbol is the letter X.

Girls lured out into the dark woods—this is the stuff of folk tales from so many countries, a New World fear of the Puritans, an image at the heart of witchcraft and the occult, timeless. Some of our best-known folk tales were passed down by teenagers—specifically teenage girls.

When Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm published their first collection in 1812, they’d collected many of the stories from young women—from a handful of lower-class villages, but also from the far more sophisticated German cities of Kassel and Münster. At least one of the girls—Dortchen, a pharmacist’s daughter Wilhelm would later marry—was as young as twelve. In their earliest published form, 125 years before the first Disney adaptation, these stories are closer to the voices of the original storytellers, less polished, blunt.

The common belief is that many of these tales, when told to children, serve as warnings for bad behavior, harsh lessons, morality plays. But on the flipside, they’re remarkable for their easy violence and malleable moral logic, like that of a child. Even mothers are potential villains (converted to stepmothers in later editions); even the youngest protagonists may kill or maim—as in Dortchen’s story of Hansel and Gretel, who burn that evil old woman alive in her own oven. Punishments are meted out, but unevenly; one offending parent meets her death, while the other is forgiven for his sadistic deed—the smoothest path to a happy ending.

The sense that these stories, however peculiar or perverse, rose up from the heart of the culture, seemingly authorless, gives them a unique authority. It is part of why they endure. The same can be said of religious allegories and rituals, or, today, of the new legends that emerge from the internet with the barest of contexts and the illusion of timelessness; timeless elements, those that seem to transcend our moment, are essential to the spinning of myths. The characters are archetypes, blank, faceless—“the girl,” “the boy,” “the old woman”; the settings are those of epics—a faraway castle, a mountain few can summit, a dark forest.

Nearly a third of the original eighty-six tales of the Grimms’ collection feature young people, many of them girls, making their way into the woods—lured out by a trickster, or the need to pass a life-or-death test. In these stories, to enter the forest is to exit everyday life, leaving its rules behind; to encounter magic, and sometimes evil; and finally, deep within the tangle of trees, to be initiated, transformed—maybe even to conquer death—in order to cross into the next phase of life. To enter the forest is to cross over into adolescence.

The woods are also (according to common knowledge) the natural domain of witchcraft, the site at which wayward women gather in the dead of night, naked, to conspire against their neighbors, to blight the crops, to make blood pacts with the devil. They travel out to the edge of town—out into the darkness, between the tops of trees, carried through the night air by demons. At least, this was the Puritan nightmare. In the first American settlements, simple houses stood close together, without streetlights to guide the way at night, and a dark wilderness stretched out just beyond the town limits. The settlers clung for comfort and stability to their vision of a harsh and unforgiving god—but the woods beyond were free from authority.

There are also the woods as they belong to the Pagans of today—those we usually mean when talking about present-day witchcraft in this country. For the Pagan movement, nature is the seat of the sacred, and the black trees the architecture of a natural temple. There the witches—Pagan priests, many of them women, some of them naked—gather for ritual. In that renegade space, they circle out under the moon, chanting, invoking their gods and goddesses.

Then there are the generations of adolescent girls who have experimented with witchcraft—whether some form of Paganism, or folk spells, or totally improvised rites and incantations. For them, the woods have been an occult “room of one’s own,” a site at which to assert that they are separate and unique, a place to be unseen and un-self-conscious. This is an impulse, untrained: As Emily Dickinson writes, “Witchcraft has not a pedigree, / ’Tis early as our breath.” Girls are drawn out from their homes, even in the cleanest of suburbs with their bright glass malls, drawn to seek out some kind of magic; to be surrounded by trees, wrapped in the dark, hidden; to become perfect, if only for an hour.

To be an adolescent girl is, for many, to view yourself as desperately set apart, powerfully misunderstood. A special alien, terrible and extraordinary. The flood of new hormones, shot from the glands into the bloodstream; the first charged touches, with a boy or a girl; the first years of bleeding in secret; the startling feeling that your body is suddenly hard to contain and, by extension, so are you. It’s an age defined by a raw desire for experience; by the chaotic beginning of a girl’s sexual self; by obsessive friendships, fast emotions, the birth and rebirth of hard grudges, an inner life that stands outside of logic. You have an undiluted desire for private knowledge, for a genius shared with a select few. You bend reality regularly.

Add to this heightened state a singular intimacy with another girl who feels the same isolation—you’ve encountered the only other resident of your private planet—and the charge is exponentially increased.

There may only be one other crime, committed by girls, that closely evokes that of Morgan and Anissa. It took place sixty years earlier, in 1954, in New Zealand.

Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme met at their conservative all-girls’ school in the Victorian city of Christchurch and became the closest of friends. Pauline was sixteen and Juliet only a few months younger. It was an unexpected friendship, as their families had little in common: Pauline’s parents were working-class (her father ran a fish-and-chip shop), while Juliet’s were wealthier and well traveled, from England, her father the rector of the local university. But the girls had something that drew them together: They’d both been sickly children—Pauline with osteomyelitis (which left her with a limp) and Juliet with pneumonia (which would lead to tuberculosis)—and that brought with it a peculiar kind of isolation. Excused from gym class, the pair spent that period walking through the yard holding hands; they spoke almost exclusively to each other. The headmistress took Juliet’s mother aside to express her concern that the girls might be growing too close—but Hilda Hulme did not want to interfere.

From this closeness the two built a wholly immersive imaginative life. They bonded through regular sleepovers at Juliet’s house, and the swapping of chapters of the baroque novels they were writing, packed with tales of doomed romance and adventure. Pauline was stocky and boyish, with short black hair and a scar running down one leg; Juliet’s hair had blond highlights, and she was taller and slimmer and wore well-tailored clothes. Pauline, who shuffled when she walked, was often ready to lash out; Juliet carried herself with the elegance and easy confidence of an aristocrat. They called each other by secret pet names based on their fiction (Pauline was “Gina” and Juliet “Deborah”). They dreamed of running away together to America, where their work would be published to great acclaim and adapted for film. They rode their bikes far into the countryside, took off their jackets and shoes and socks, and danced until they were exhausted. Some late nights, Pauline would sneak away and ride her bike to Juliet’s house, where Juliet would slip out through a balcony. They would steal a bottle of her parents’ wine and drink it somewhere out on the grounds, or ride Juliet’s horse through the dark woods.

On a bright June afternoon in 1954, Pauline and Juliet took a walk through a local park with Pauline’s mother—the place was vast (about 200 acres), with a few hiking paths cleared between the young pines and outcroppings of volcanic rock. When they’d gotten far enough away from any other visitors, Juliet provided a distraction—a pretty pink stone she planted on the ground—and as Honorah Parker bent down to take a look, Pauline removed a piece of brick she’d hidden in her bag, wrapped in a school stocking, and brought it down on her mother’s head. The woman collapsed to the ground, and the girls took turns bludgeoning her—about forty-five blows to the head, her glasses knocked from her face, her dentures expelled from her mouth—until she was dead.

According to Pauline’s journals, in the year leading up to the murder Pauline and Juliet had created their ownreligion, unimpressed by Christianity and inspired by elements in their lives both secular and sacred. They’d drawn on the Hollywood movies at their local theater for their coterie of “saints” (Mario Lanza, Orson Welles, Mel Ferrer), erected a “temple” (dedicated to the Archangel Raphael and to Pan) in a secluded corner of Juliet’s backyard, and marked their personal holidays with elaborate, choreographed rituals. They believed they could have visions at will—visions of a “4th World” (also called “Paradise” or “Paradisa”), a holier realm inhabited by only the most transcendent of artists, a plane of existence far above that of Pauline’s father, with his fish-and-chips shop, or her undereducated mother. With enough practice, each would soon be able to read the other’s mind. Each made the other singular and perfect.

What eventually drove Pauline and Juliet to kill Pauline’s mother was the fear of being torn apart: Juliet’s parents, who were separating, wanted Juliet to stay with her father’s sister in Johannesburg while they prepared to return to England; Honorah had refused to allow Pauline to go along. If this were to happen, the world they’d built together—over so many daydreamy afternoons and secret nights out among the trees—would collapse. The girls could not permit that.

In April of 1954, Pauline wrote: “Anger against mother boiled up inside me. It is she who is one of the main obstacles in my path. Suddenly a means of ridding myself of the obstacle occurred to me.”And then in June, a series of entries:

We practically finished our books today and our main like for the day was to moider mother. This notion is not a new one, but this time it is a definite plan which we intend to carry out. We have worked it all out and are both thrilled with the idea. Naturally we feel a trifle nervous but the anticipation is great.

We discussed our plans for moidering mother and made them a little clearer. Peculiarly enough I have no qualms of conscience (or is it peculiar we are so mad?).

I feel very keyed up as though I were planning a surprise party. So next time I write in this diary Mother will be dead. How odd yet how pleasing.

And early on the morning of June 22, on a page of her journal labeled, in curling letters, “The Day of the Happy Event”: “I am writing a little of this up on the morning before the death. I felt very excited and ‘The night before Christmas-ish’ last night…I am about to rise!”

For five months before the stabbing, Morgan and Anissa discussed how they would kill their friend. They learned to speak in their own private code: “cracker” meant “knife”; “the itch” was the need to kill Bella; their final destination, the Nicolet Forest, was “up north” or “the camping trip.”

Like those girls in Christchurch, they were drawn to each other out of loneliness. Each saw the other as an affirmation of her uniqueness; they shared a hidden, ritualized world. But Morgan and Anissa’s private universe was spun not from the matinee idols and historical novels of the early twentieth century but from the online fictions of our own time. They had devoted themselves to an internet Bogeyman.

Like a fairy-tale monster, Slender Man emerged through a series of obscure clues, never fully visible. He first appeared online, in the summer of 2009, in two vague images that were quickly passed around horror and fantasy fan forums. In the first, dated 1983, a horde of young teenagers streams out of a wooded area toward the camera, while behind them looms a tall and pale spectral figure with its hand outstretched. The image is coupled with a message: “We didn’t want to go, we didn’t want to kill them, but its persistent silence and outstretched arms horrified and comforted us at the same time…” In the second photo, dated 1986, we see a playground full of little girls, all about six or seven years old. In the foreground, one pauses to face the camera, smiling, as she climbs a slide; in the background, in the shade of a cluster of trees, others gather around a tall figure in a dark suit. If you look closely, you can make out wavy arms or tentacles emanating from its back. A label states that the photo is notable for being taken on the day on which “fourteen children vanished,” and as a record of “what is referred to as ‘The Slender Man.’” Making this all the more meta-real, these photos were presented as “documents”: The 1986 image bears a watermark from “City of Stirling Libraries”; the photographers, respectively, are listed as “presumed dead” and “missing.”

These images were created by a thirty-year-old elementary-school teacher (Eric Knudsen, who goes by the name “Victor Surge”) in one of the collections of forums on the website Something Awful. Surge decided to take part in a new thread called “Create Paranormal Images.” The game was to alter existing photographs using Photoshop and then post them on other paranormal forums in an attempt to pass them off as the real thing. The monster was deliberately vague, his story almost completely open-ended—and so the internet rushed in to make of him what it wanted. Bloggers and vloggers and forum members wrote intricate false confessionals of encounters with Slender Man, and posted altered photographs and elaborate video series all predicated on the assumption that “Slender” was a real entity and a real threat.

Over the next several years, the monster spread at an exponential rate, mainly through alternative-reality games—online texts and videos created by fans feeding off the narratives of other users in real time, creating a “networked narrative” that blurs the lines between reality and fiction. And as the story spread, it quickly lost its point of origin, becoming instead the creative nexus, for hundreds of thousands of users, of a dark, sprawling, real-time fairy tale. A sort of 4th World.

All that users knew at first was that Slender had the appearance of a lean man in a black suit, and there his humanoid features ended. He is unnaturally tall—sometimes as tall as twelve feet—and where his face would be is only blanched, featureless skin, stretched taut as a sausage casing, with shallow indentations in place of eyes and mouth. Occasionally, when he shows himself, a ring of long, grasping black tentacles, like supple branches, emerges from his back. Slender Man’s motives are unclear, but he is associated with sudden disappearance and death. And he has a pronounced appetite for children. Like a gothic Pied Piper, he calls the children out and leads them away from their world, never to be seen again. And when he allows them to stay in their suburban homes, he infects them with the desire to kill, and the longing to be initiated into his darkest, innermost circle.

Slender Man, his fans have decided, has a peculiar attachment to the woods. Any woods, anywhere. Elaborate Photoshopped images populate the internet—of Slender lurking in the trees at the edges of suburban backyards, or appearing in the background of snapshots taken by unsuspecting hikers. Scores of YouTube clips show twentysomethings running through the woods, chased by Slender Man (who sometimes even makes an appearance, in a bad suit, on stilts, with a white stocking over his head). And then there are the “archival” photos, of historical Slender Man sightings around the world. One of the most arresting images shows Slender standing among the massive pines of a half-felled forest behind children in what might be nineteenth-century dress: It could be an early photo of Appalachia, or perhaps the Black Forest (some believe the monster first emerged long ago in Germany, the birthplace of some of our darkest folk tales).

For Slender’s hundreds of thousands of online devotees he was a trip, a monster they were crowdsourcing in real time. His many, many fans and cocreators were mostly college-age guys, or guys in their early twenties—people with a lot of time to devote to the unreal. But because the internet is so wide open, and because there were so many avenues leading to Slender—from video games like Minecraft (where Anissa Weier first discovered him) to alternate-reality games, entire YouTube channels, and fan-fiction forums—there was no way to control who was exposed to this new monster and what they made of him. Morgan and Anissa, among the youngest members of the Slenderverse, were quickly consumed by the swirling, open-ended storyline. They latched onto him as a source of private ritual, the linchpin in the occult universe they were building together.

From the beginning, their friendship was forged by a kind of urgency. Anissa, in particular, suffered from bullying after recently transferring to their school (a fact she kept from her parents) and needed this months-old bond with Morgan to last. (Morgan would later claim that she’d gone ahead with the stabbing to keep Anissa “happy”: “It’s, um, hard enough to make friends, I don’t want to lose them over something like this.”) Their bond was only heightened by the alternate reality they inhabited together.

The Slender Man phenomenon actually feeds on the divide between young people’s reality and that of adults: He exists, he grows, in the gap between adolescents’ intuitive sense of the truth—their willingness to embrace the Mysteries—and the cool logic of their parents and teachers. “It should also be noted that children have been able to see [Slender] when no other adults in the vicinity could,” reads one fan site. “Confiding these stories to their parents [is] met with the usual parental admonition: overactive imaginations.”

The girls told each other they could see Slender and hear Slender, and in her notebooks Morgan drew the image of the faceless man again and again.

In Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692, a dark story spun by a cadre of teenage girls had radical real-world consequences.Their false accusations were as fantastic as any folk tale—a form that had become popular in Europe earlier that century—and as starkly good versus evil as the biblical drama that their harsh Puritan community thrived upon.

The “afflicted girls” of Salem—Abigail Williams and ten others—charged their neighbors with consorting with the Devil, and of tempting them to do the same. Abigail Hobbs, then fourteen, openly rebelled against her stepmother and claimed to wander the woods at night. She told everyone who would listen that she had no fear and nothing could harm her—she’d made a pact with Satan! Most outrageous of all, she said that she’d taken part in a gathering of nine witches during which they’d consumed an unholy sacrament. “I will speak the truth,” she told the crowd when called into court. “I have been very wicked.”

As the Slender Man legend evolved, the shadowy figure operated more like the Satan of Puritan times. Posters claimed that anyone who learned about Slender was in danger of becoming obsessed with him through a kind of mind control; increasingly, he killed through others—humans known as his “proxies,” his “husks,” his “agents.” He took possession of them, and they did his bidding.

The fairy-tale concept of evil lurking in the woods may be as old as the idea of Satan himself. And all of them—children’s monsters, Slender Man, the Devil—are kept alive by the stories we tell one another. Abigail Williams claimed to have a vision of elderly Rebecca Nurse offering her “the Devil’s book”; in church, she cried out that she saw another of the village women perched high in the rafters, suckling a canary; she spotted malicious little men walking the streets of town recruiting new witches. Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme’s visions were more mystical and ethereal. Two months before the murder, over Easter vacation, Pauline stayed with Juliet and her family at the beach, and the pair had their first shared revelation. On Good Friday, out for a walk before sunrise, they saw what Pauline described as a “queer formation of clouds,” “a gateway” into the 4th World. They suddenly realized that they had “an extra part of our brain which can appreciate the 4th World…[W]e may use the key and look into that beautiful world which we have been lucky enough to be allowed to know of.”

As for Morgan and Anissa, in Waukesha, they, too, shared visions they claimed were tangible, hyper-realistic. Like the adults posting on Slender Man forums, the girls told each other that they were able to see “Slendy”—but with a vivid reality that set them apart from any healthy adult fan. According to Anissa, after she first told Morgan about the monster, Morgan claimed she’d spotted him when she was five, in a wooded area near her family’s house. Anissa told Morgan that she’d seen him twice, in trees outside the window of the bus they shared to school.

When a detective questions Anissa shortly after her arrest, she asks, “So back in December or January, Morgan told you, ‘Hey, we should be proxies,’ basically?”

anissa: Yeah.

detective: And you said what?

anissa: I said, “Okay, how do we do that?” And she said, “We have to kill Bella.”

detective: Okay. [Pause.] And do you know why she said that?

anissa: Because we had to supposedly prove ourselves worthy to Slender.

detective: And what did you think of this?

anissa: I was surprised—but also kind of excited, ’cause I wanted proof that he existed. Because there are a bunch of skeptics out there saying that he didn’t exist, and then there are a bunch of photos online and sources online saying that they did see him…So I decided to go along, to tag along, to prove skeptics wrong.

detective: So did you think that you actually had to kill someone to do it?

anissa: Yeah.

detective: Like, for real?

anissa: Mm-hmm.

About an hour into the interrogation, the detective asks Anissa, “When Morgan said to you, ‘If we don’t do this for Slender, our families and loved ones will be killed,’ do you honestly believe that?” Anissa, crying, answers in an astonished-kid voice: “Well, yeah.” More specifically, she believes that Slender Man “can easily kill my whole family in three seconds.” Just hours earlier, during their long trek to the Nicolet Forest, the girls had announced each time they’d caught a glimpse of him along the way—in the suburban woods, among the trees by the highway. They could hear the rustling of him following close by.

Morgan Geyser’s drawings of Slender Man veer from stark, repetitive images evoking a phantom—a page covered in his symbol (“X”), a blank face with Xs for eyes—to the increasingly particular. In one pencil sketch, a girl with kitty-cat ears and tail lies on the ground, eyes closed, a skull floating above her head; looming over her is another humanoid kitty-girl, who looks straight at the viewer, a scythe in one hand. The speech bubble above her head reads: i love killing people! And in the most elaborate image, a slim, bald, and faceless figure towers over a row of children; enormous, octopoid tentacles emerge from his back, like long black fingers.Above this Slender-creature’s head is written a message, as if to the artist herself: you are strange child…it will be of my use.

In that inscription, an adolescent girl, channeling the voice of a monster, exiles herself—she is “strange” and warped—only to accept herself again. The monster tells her, Here in the Slenderverse, your strangeness is unique; your loneliness has a purpose; I am calling you to your destiny. Just as in the 4th World, Pauline and Juliet’s weirdness, their “madness,” gives them psychic powers and untouchable brilliance. By some Brothers Grimm logic, a dark trial, a call to murder, becomes the girls’ only prospect. On ten separate occasions in her interrogation, Morgan calls the stabbing “necessary.”

In another sketch, a longhaired kid in a bloody sweatshirt looks as if she has thrown her arms around the neck of Slender Man, who embraces her in return. She is crying; his reddened cheeks are either bloodied or blushing. The two appear to be close, intimate; they are, perhaps, comforting each other. Here the meaning of that earlier inscription—he still sees you—seems to change. As if following the plotline of a teen romance, perhaps Slender’s message has become, instead, i see who you really are. Slender Man has inspired reams of online fan fiction, some of it romantic or even erotic, about teenage girls involved with the monster. Titles include “My Dear Slenderman,” “Into the Darkness,” “Love Is All I Want,” “To Love a Monster,” “I Slept with Slender Man,” and “Slenderman’s Loving Arms.” A few of these stories have some 150,000 reads.

The occult is orphic, a word meant to evoke Orpheus and his dark romance. An ancient Greek myth tells of how, after the death of the musician’s wife, he followed her into the underworld—only to fail at his one chance to bring her back to life. To build a private, occult world with someone is to travel with them into the dark—and the danger inherent in that is, inevitably, erotic.

Months before her mother’s murder, Pauline Parker was sent to see a doctor at the suggestion of Juliet Hulme’s father: He was concerned that his daughter’s friend might be a lesbian. At their trial, there was much speculation about a possible sexual relationship between the two—a romance perhaps born out of their shared writings and nighttime escapades in the garden. Even putting aside the possibility of a lesbian romance, any sexuality for an unmarried woman, never mind a girl, was liability enough in the 1950s. When the case went to trial, the Crown prosecutor asked his witnesses leading questions about “orgies” and “sexual passion.”

And what of the girls of Salem, and what they claimed to have seen of the dark? Abigail Williams was made notorious by Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible (which premiered, incidentally, the same year Pauline and Juliet met); she became the lead harpy, the great finger-pointer, a seventeen-year-old girl capable of sending men and women to their deaths, embittered by her affair with local farmer John Proctor. But, in reality, Abigail was only eleven in 1692, and Proctor was sixty. Miller made large assumptions about what shaped her; he spun her story into one of young, female sexuality as a corrupting force. In Miller’s play, she has suddenly come into the sexuality of an adult, but with an adolescent’s inability to control her impulses. A new darkness—a dark eroticism and sexual envy—infuses his character’s thoughts, has lured her out into the woods, out past the borders of good society, in search of a hex. And when she levels her accusations, her conviction is as compelling, as unassailable, as that of a child.

At the same time, in both Christchurch and Waukesha, the attacks were striking in their childishness. In spite of the girls’ months of secret talks and journaling and to-do lists, when carried out, the attacks were stupid and clumsy; they had no idea what they were doing. Some of the details they had thought through were fairy-tale specific: Juliet’s idea to distract Honorah Parker with a pink gemstone she placed on the park path (Parker stooped down to examine it before Pauline struck); Anissa’s idea to lead Bella into the woods through the offer of a game of hide-and-seek. Think of the fact that Morgan and Anissa could still lure their friend into the woods through such a simple game; the bursts of energy with which that game is played; and Bella “hiding” from people she should truly have hidden from. Picture her attackers out there in the suburban woods, playing in high spirits—and then turning to another game, a dare, passing the knife back and forth between themselves until Anissa gives an order clear enough to bring their play to an end. That morning, Morgan brought the knife with her in the way that she might have brought a wand to a Harry Potter movie screening. And perhaps she believed that she could perform magic with a toy—but that idea brought with it no real-world consequences. Playing with a knife, of course, did.

Their childish incomprehension of the gravity of violence, and the callousness that comes with that, is painfully evident in the girls’ interviews while in custody. When Anissa describes her nervousness as they approached the playground that morning, the detective asks what she was most nervous about. She answers, “Seeing a dead person. ’Cause the last time I saw a dead person it was at a funeral and it was my uncle.” When asked what Morgan was upset about in the park, Anissa says, “Killing. She had never done that before. She’d stabbed apples before—with, like, chopsticks—but she’d never actually cut a flesh wound into somebody.”

Pauline and Juliet continued to behave like immature girls, unaware of what was at stake, even after their arrest. When Pauline was taken into custody alone—at first, police believed Juliet was not directly involved—she didn’t want to break her habit of journaling, and so she wrote a new entry, stating that she’d managed to pull off the “moider” and was “taking the blame for everything.” (A detective on the case quickly seized it as evidence.) Once both girls were at the station, sharing a cell, they were placed on suicide watch—but they spent their first night (a police officer would later report) gossiping in their bunk beds, unconcerned about their new environment. During the trial, about a dozen foreign publications were represented in the courtroom, with most British newspapers printing a half-column daily, often on their front page—rare attention for a New Zealand case. In a courtroom packed with spectators, Pauline and Juliet were out of sync with the tone of the proceedings. Seated together in the dock, they appeared relaxed and indifferent, often whispering excitedly to each other and smiling. One journalist described their attitude throughout as one of “contemptuous amusement.”

Then there is the physical fact of just how young all four of these girls were at the time of their crimes, Morgan and Anissa in particular—something driven home by their regular images in the press. After three and a half years in custody, Morgan’s and Anissa’s faces are recognizable. Their booking photos, published as a single splitscreen image, are iconic: These suspects have the round cheeks and unfashionable eyeglasses of children. Photos from their first hearings show the two in dark blue jail uniforms, their handcuffed wrists locked to shackles around their waists; at the same time, they are petite (the size of twelve-year-olds) and flat-chested. By their 2016 hearings, both girls, photographed in an array of cotton day dresses, have clearly entered puberty, with developed breasts; their bodies are transforming into those of young women right in front of us, their adolescence taking place in captivity. Anissa’s hair, once cut just below her chin, now falls a few inches below her shoulders. Here it is made visible: the uneasy border between “child” and “adult,” between the softness of girlhood, still visible in their baby fat, and the latent sexual threat of early womanhood, newly visible.Did the changes in their bodies increase the chance of them paying a greater price for their crime?

Wisconsin law allows for anyone age ten or above to be tried as an adult for a violent crime. This ratchets the stakes up much, much higher: Both Morgan and Anissa were initially charged with first-degree intentional homicide, facing up to forty-five years in prison (they both pled not guilty for reason of mental illness or defect). If the judge had allowed both their cases to be moved to juvenile court, they would have remained in a juvenile facility, set for release at eighteen.

In the earliest days of this country, American jurisprudence followed the doctrine of malitia supplet aetatem—or, as translated, “malice supplies the age.” Following the example of English common law, a child of seven or older who understood the difference between right and wrong—as if these were simple, stable concepts—could be held fully accountable. He could even be eligible for the death penalty. As Blackstone’s Commentaries summed it up, in the 1760s, “one lad of eleven years old may have as much cunning as another of fourteen.” It was not until more than a century after the founding of the United States, in 1899, that a juvenile court system was established. Industrialization had made clearer the need to protect children as a separate class—or, in Jane Adams’s words, to create a court that would ideally play the role of the “kind and just parent.”

But the biggest shift in juvenile justice has been our evolving understanding of the adolescent brain. Neuroscience research has shown that the prefrontal cortex is not fully developed until twenty-five years old, impairing a person’s impulse control. There is also the lack of emotional development: The Supreme Court has described adolescence as “a time of immaturity, irresponsibility, impetuousness, and recklessness.” As recently as 2005, the court outlawed the execution of minors as “cruel and unusual punishment,” in a case in which the American Medical Association and the American Psychological Association filed briefs on new research into adolescent brain development. The same ruling leaned heavily on a 2002 case that prohibited the execution of individuals with intellectual disabilities: Because juveniles are immature, “their irresponsible conduct is not as morally reprehensible as that of an adult.” The Supreme Court was not arguing that adolescence is a kind of mental disability, but perhaps that both share symptoms in common—vulnerability, instability, a skewed or heightened worldview—that render their actions harder to judge.

One of the earliest entries into the Grimms’ original collection—one that would never make it into the later, popular edition—is a story called “How Some Children Played at Slaughtering.” Like all the Grimms’ folk tales, it is short and terse, and it goes something like this: In a small city in the Netherlands, a group of children are playing, and they decide that one should be the “butcher,” one the “assistant,” two the “cooks,” and another, finally, the “pig.” Armed with a knife, the little butcher pushes the pig to the ground and slits his throat, while the assistant kneels down with a bowl to catch the blood, to use in “making sausages.”

The kids are discovered by an adult, and the butcher-boy is taken before the city council. But the council doesn’t know what to do, “for they realized it had all been part of a children’s game.” And so the chief judge decides to perform a test: He takes an apple in one hand and a gold coin in the other and holds them out to the boy; he tells him to pick one.

The boy chooses the apple—laughing as he does, because in his mind, he’s gotten the better deal. Still operating by a child’s logic, he cannot be convicted of the crime. The judge sets him free.

In the months before Bella’s stabbing in 2014, Morgan Geyser, nearly twelve, was both entering into adolescence (she had just gotten her period) and descending into mental illness.

After her initial five-hour interview came to an end, Morgan, still without her parents, in clothes and slippers provided by the Waukesha police, was placed in the Washington County Jail for juveniles. Anissa was there, too, but they were not allowed to interact. Morgan could have no visitors other than her parents, who were required to sit on the other side of a glass divider; only after a few months into her stay was she permitted to touch or hold them, and even then only twice a month. Over the summer, she became, as her mother, Angie, described her, “floridly psychotic.” She continued to have conversations with Slender Man, as well as characters from the Harry Potter series (at one point, she claimed that Severus Snape kept her up until 3 a.m.); she saw unicorns; she treated the ants in her cell like pets.

In the fall of that year, Morgan was moved to the Winnebago Mental Health Institute for a few months of twenty-four-hour observation, to determine if she had a chance of being competent enough to stand trial. There, she was given a psychological evaluation that concluded that she suffers from early-onset schizophrenia—very rare for someone so young. Her state-appointed doctor learned that Morgan, since the age of three, had been experiencing “vivid dreams which she wished she could change”; and in the third grade, she began “seeing images pop up on the wall in different colors.” She believed she could see ghosts and feel their embrace. At a hearing in December 2014, the judge found Morgan capable of standing trial and ordered her back to Winnebago for treatment—but the facility could no longer take her, now that she had been deemed “competent.” Her parents asked for her $500,000 bail to be reduced to a signature bond so that she could be moved to a group home for girls with mental and emotional issues, but the request was denied because the home was not considered secure enough.

By late 2015, Morgan Geyser, diagnosed with schizophrenia, was still not being treated for her disease. She’d become attached to her visions and feared losing them, her only companions in her isolation. Alongside her “friends,” she wandered through the forest of her thoughts.

Carl Jung took long walks through the sprawling Black Forest as a teenager, during which he improvised his own strain of Pagan mysticism, communing with the trees. He spoke of that same wilderness in a lecture in 1935, as the opening setting of the fifteenth-century romance Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: The novella begins, “At length my ignorant sleepes, brought me into a thick wood,” and then descends, as Jung describes it, “into the underworld of the psyche.” Jung said that forests, as dream imagery, were “symbols for secret depths where unknown beings live.” (His mentor, Sigmund Freud, wrote of his own method of analysis as a walk through “a dark forest.”) In Jung’s Liber Novus (also known as The Red Book), completed around 1930, he wrote of the nature of the human imagination: “Thoughts are natural events that you do not possess, and whose meaning you only imperfectly recognize…[T]houghts grow in me like a forest, populated by different animals.”

Morgan’s hallucinations—magical characters speaking to her, imaginary friends, lifted from the pages of books or the internet—are grounded in something more specific: her genetic inheritance. Her father, Matt, began his lifelong struggle with schizophrenia at fourteen years old (he receives government assistance due to his illness). In a recent documentary, Beware the Slenderman, he talks about his coping mechanisms for living with schizophrenia: He runs numbers in his head and tries to “put up static” to block out his visual and auditory hallucinations. Matt and his wife, Angie, decided early on to delay sharing the fact of Matt’s illness with their daughter until she grew older—why make her fearful of a genetically inherited disease that she might never have to face? She’d shown no clear warning signs.

In the film, Matt Geyser describes a life in which the boundaries between the real and the unreal are painfully blurred and an intellectual understanding of the difference is not enough to protect you. If, earlier on, he had decided to share his burden with Morgan, this is the picture he might have drawn for her: “Right now there’s, like, patterns of, like, light and, like, geometric shapes that’s like, always racing—like always, like right now. Everything seems normal to me ’cause this is my everything; this is how I’ve always seen things.” But the more threatening hallucinations—including, he says, a “glaring demon-devil”—are more complicated. “You can, like, see it, and, like, you know it’s not real. But it totally doesn’t matter because you’re, like, terrified of it,” he says, becoming emotional. “I know the devil’s not in the backseat, but—the devil is in the backseat. You know?”

In January 2016, after nineteen months without treatment, Morgan was finally committed to a state mental hospital and put on antipsychotics. By spring, her attorney claimed that her hallucinations were receding and her condition was improving rapidly. But in May of that year, after two years of incarceration, Morgan attempted to cut her arm with a broken pencil and was placed on suicide watch.

Late this September, Morgan accepted a plea bargain, agreeing to be placed in a mental institution indefinitely and thus avoiding the possibility of prison. Just weeks earlier, Anissa had also accepted a deal, pleading guilty to the lesser charge of attempted second-degree homicide. A jury recommended she be sent to a mental hospital for at least three years.

The joint trial of Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme also hinged on the question of their mental health. Were the girls delusional? Clinically paranoid? Or had they been completely aware of the consequences of their actions and chosen to go ahead with their plan regardless? The defense argued that the girls had been swept up in a folie à deux, or “madness between two”—a rarely cited, now-questionable diagnosis of a psychosis developed by two individuals socially isolated together. The crime was too sensational and the defense too exotic for the jury to be persuaded. They deliberated for a little over two hours before finding the girls guilty.

Juliet got the worst of it. She was sent to Mt. Eden prison in Auckland, notorious for its infestation of rats and its damp, cold cells (particularly bad for an inmate who’d recently suffered from TB). There Juliet slept on a straw mattress and had one small window she could not see out of; the bathrooms had no doors, and sanitary napkins were made from strips of cloth. She split her time between prison work (scrubbing floors, making uniforms in the sewing room) and writing material the superintendent called “sexy stuff.” She gorged herself on poetry: Byron, Shelley, Tennyson, Omar Khayyám. She taught herself Italian—she dreamed of making a living as either a writer or a singer of Italian opera—and she bragged in a letter that she and Pauline were exquisite singers. She also bragged about her studies, even her talent in knitting—she bragged incessantly. In a letter to a friend, Juliet’s father worried that she was “still up in the clouds…completely removed and occupied with herself and her grandiose ideas about poetry and writing.” Five months after the crime, Juliet was “still much the same as she was immediately after the event. She feels that she is right and others are wrong.” She remained unbowed, still immersed in literature and a vision of the great artist she could become. These were “delusions” she was not willing to let go of.

In spite of the harsh conditions of Juliet’s incarceration, the girls’ sentences were ultimately lenient. After five and a half years, both were released by order of the executive council, and each was able to start her life over under an alias.

Juliet Hulme, now Anne Perry, moved to England; using the shorthand she learned in prison, she got a job as a secretary. But she hadn’t lost sight of her and Pauline’s plan to one day move to California. When she was turned down for a visa (her criminal history was hard to overlook), she began working as a stewardess for an airline that often flew to the United States. One day, upon arriving in Los Angeles, she disembarked and never got back on the plane. She rented a lousy apartment, took on odd jobs, and wrote regularly. By her thirties, back in England, she’d launched a career as a crime novelist. She has since published more than fifty novels, selling over 25 million books worldwide.

In one of her earlier novels, the lead murder suspects seem inspired by Pauline and Juliet: a slightly androgynous suffragette and the taller, radiant, protective woman with whom she lives. They are brilliant and fearless; the suffragette’s partner is exalted as having “a dreamer’s face, the face of one who would follow her vision and die for it.” In a later book, the detective-protagonist seems to speak for the unconventional mores of the author herself when he states that “to care for any person or issue enough to sacrifice greatly for it was the surest sign of being wholly alive. What a waste of the essence of a man that he should never give enough of himself to any cause, that he should always hear the passive, cowardly voice uppermost which counts the cost and puts caution first. One would grow old with the power of one’s soul untested…”

The next chapter of Pauline’s life was not marked by such bravado. She became Hilary Nathan and eventually moved to a small village in South East England. There she purchased a farmworker’s cottage and stables, and taught mentally disabled children at a nearby school; she attended daily mass at the local Catholic church. After retiring, she gave riding lessons at her home. When her identity and location were revealed in the press in 1997, Pauline, then fifty-nine, quickly sold her property and disappeared.

She left behind an elaborate mural, on the wall of her bedroom, that the buyers believed she had painted herself—a collection of scenes that are part fairy-tale illustration, part religious allegory. Near the bottom, there is an image of a girl with dark, wavy hair (like her own) diving underwater to grasp an icon of the Virgin Mary; in another, the same girl—as a winged angel, naked and ragged—is locked in a birdcage. At the mural’s peak, a beautiful blonde (a girl who resembles Juliet) sits astride a Pegasus—glowing, exuberant, arms outstretched. And the blonde appears again, on horseback, seemingly about to take flight, as the Pauline figure tries to bridle the animal.

On display in these images is both the narcissism of adolescence and the remorse of adulthood, the penance of a woman who has resolved herself to receive the sacrament every single day. And what bridges these two elements is an image at the mural’s center: the Pauline girl seated, head bowed, under a dying tree against a dying landscape. The occult language of nature—those late nights in the garden, those dark plans in the woods—had nothing left to give her. It had lost its pagan power.

A powerful narcissism is in full view during the interrogation of Anissa Weier. After being arrested for the stabbing of Bella Leutner, the first question Anissa asks the detective is not about her friend’s condition (that would not happen until two and a half hours later) but about how far she and Morgan had walked that day—“’Cause I’m not usually very athletic and I just wanna know.” She seems very impressed by the challenges they’d faced on their long walk after leaving Bella, harping on the distance, the threat of heat exhaustion and mosquitoes, going without an allergy pill all day (“Is it bad?”), and the limited snacks (the granola bar she’d packed was “disgusting”; the Kudos bar was much better). She recounts with incredible precision everything she and Morgan ate that day, including free treats at a furniture store (a glass of lemonade and two cookies each). Near the end of her interview, she seems about to share a revelation with the detective:

anissa: I just realized something.

detective: What’s that?

anissa: If I don’t go to school on Monday, that’ll be the first day that I miss of school.

Anissa was later diagnosed with a “shared delusional belief”—a condition that faded the longer she was separated from Morgan. Her parents had gotten divorced just the year before and, along with the bullying at her new school, she’d been upset, unmoored—but otherwise mentally stable. While it is fairly easy, based on the video footage, to believe that something is wrong with Morgan—she is detached, spaced-out—it seems quite clear that Anissa is not ill. She appears more frightened than Morgan, more in touch with the reality of the situation, crying occasionally throughout. She doesn’t read as flighty; she doesn’t speak in a distant, spooky voice; she seems upset, but grounded. She answers questions with the eagerness and precision of a girl who wants to be the best student in class. And this is precisely why it’s so upsetting to watch footage of the following exchange, about the immediate aftermath of the stabbing:

detective: So [Bella] was screaming?

anissa: Mm-hmm. And then, um, afterwards, to try to keep her quiet, I said, “Sit down, lay down, stop screaming—you’ll lose blood slower.” And she tried complaining that she couldn’t breathe and that she couldn’t see.

detective: So she started screaming, “I hate you, I trusted you”?

anissa: Mm-hmm.

detective: She got up?

anissa: Yeah. She got up and tried to walk towards the street… It led to the other side of Big Ben Road.

detective: So she tried to walk towards the street and what happened?

anissa: And then she collapsed and said that she couldn’t see and she couldn’t breathe and also that she couldn’t walk. And so then Morgan and I kind of directed her away from the road and said that home was this way—and we were going deeper into the forest area.

detective: So she said—she fell down and said she couldn’t breathe or see.

anissa: Mm-hmm. Or walk.

detective: Or walk. And you had told her to—

anissa: To “lay down and be quiet—you’ll lose blood slower.” And that we’re going to get help.

detective: But you really weren’t going to get her help, right?

anissa: Mm, no.

At this point in the interview, Anissa is wrapped in a large wool blanket. The detective handed it to her because the space is chilly. Perhaps she was trying to gain Anissa’s confidence, or perhaps it was simply instinctive, offering comfort to a young girl being held in a concrete room. Anissa has been crying—but whether this is from genuine remorse or a kid’s fear of getting into trouble is anyone’s guess. The look on her face does not tell us enough. And now the detective reads it back to her, the story of two girls who led their friend into the woods.

1 Comments

This article is a fascinating read that I was led to from the Guardian. I do have to say that their shortened version has left out enough detail that it does the original a slight diservice, I think the Guardian version is cut in a way that muddles violence, mental illness and menstration in a slighlty confusing way that seems to mistify female adolesence and feels to me like it could contribute to a feeling of alienation rather than dispell it? I think this is exaccerbated by the lack of a clear author and omission of the opening paragraphs where the author says 'we' as it makes the story feel devoid of personal experience or understanding. I should say that this is all from the viewpoint of a young man so could be way off the mark but would be interested to hear what anyone else whose read both thinks?

Found it a fascinating read though and enjoyed it much more when I clicked through to here and read it in full.