Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

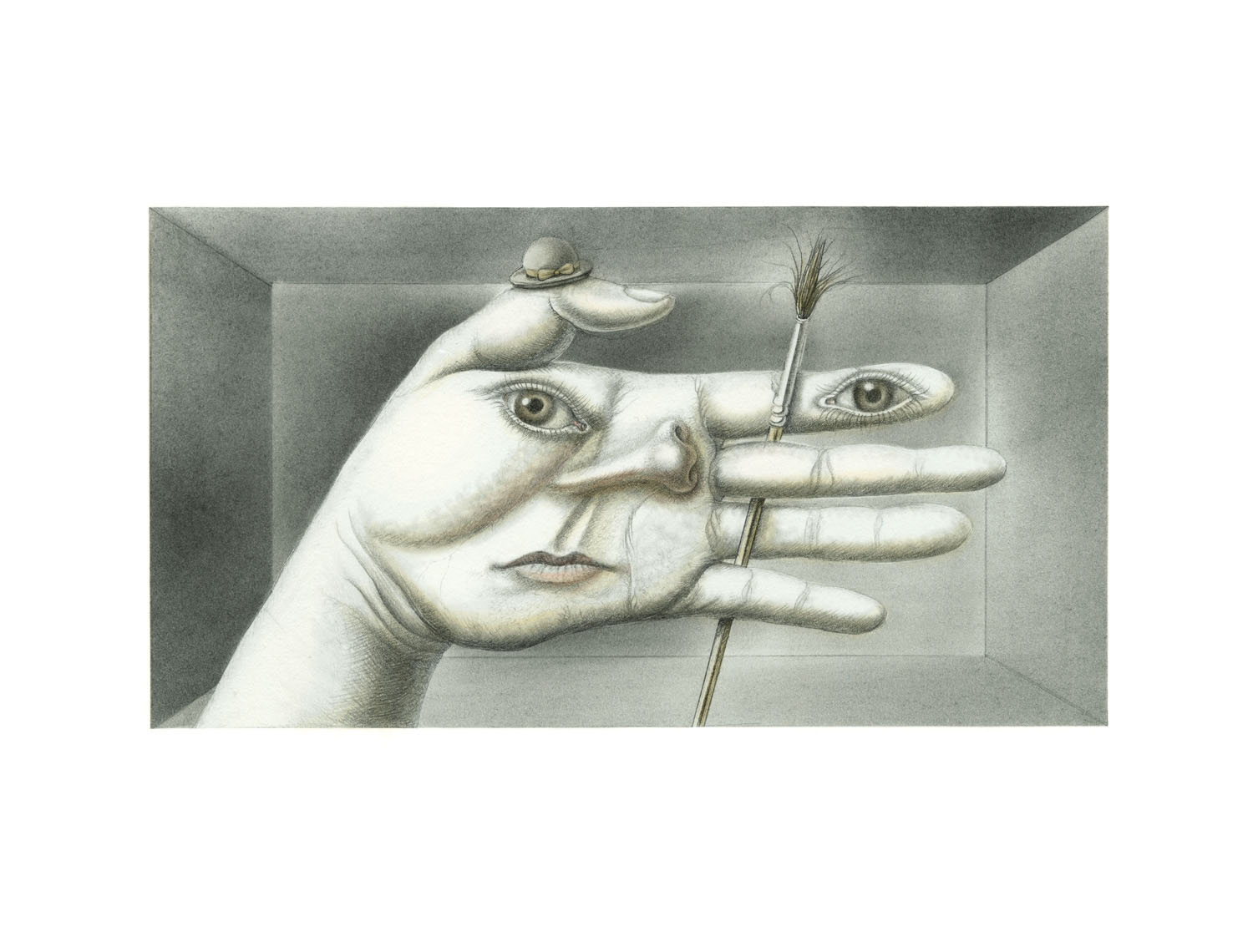

Armando Veve is an illustrator working in Philadelphia. His drawings have been recognized by American Illustration, Communication Arts, and Spectrum, and awarded gold medals from the Society of Illustrators. He was named an ADC Young Gun by the One Club for Creativity and selected to the Forbes 2018 30 under...