In 2011, the writer Yiyun Li and I were both asked to judge a fiction contest for the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. I panicked, that certain swoon-panic of the fellow author who is a fan, at her name next to mine. I was enamored of all her abilities, from mechanical to aesthetic—a certain gelid elegance, sharpness in syntax and diction, fluidity of theme in dark and light with such self-possessed strokes. And I—in my head and sometimes truly with my pen, an impulsive maximalist-stylist, always straddling rough and rougher—studied her register but found it impossible to emulate. So when we judged that contest together, I tried to calmly and coolly interact with her without a stutter. We both had agreed on the same winner almost instantly. I completely agree with you, Porochista. It’s my favorite too, so let’s go ahead with it? she wrote, words I held on to for months. Eventually I realized we had even more in common than I dared suspect: her East Asian immigrant to my West Asian immigrant, English as a second language, nuclear physicist fathers, and California as home.

In 2011, the writer Yiyun Li and I were both asked to judge a fiction contest for the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. I panicked, that certain swoon-panic of the fellow author who is a fan, at her name next to mine. I was enamored of all her abilities, from mechanical to aesthetic—a certain gelid elegance, sharpness in syntax and diction, fluidity of theme in dark and light with such self-possessed strokes. And I—in my head and sometimes truly with my pen, an impulsive maximalist-stylist, always straddling rough and rougher—studied her register but found it impossible to emulate. So when we judged that contest together, I tried to calmly and coolly interact with her without a stutter. We both had agreed on the same winner almost instantly. I completely agree with you, Porochista. It’s my favorite too, so let’s go ahead with it? she wrote, words I held on to for months. Eventually I realized we had even more in common than I dared suspect: her East Asian immigrant to my West Asian immigrant, English as a second language, nuclear physicist fathers, and California as home.

One thing I didn’t suspect we’d share was suicidal ideation. I, of course, had no idea that at the time of our judging she was just months away from a suicide attempt, while I was only one year from the worst episodes of my own lifelong depression.

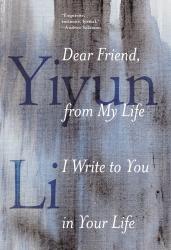

It’s hard to pinpoint the true beginning of Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life’s nonlinear tales, but so much comes back to Li’s arrival in America at age twenty-three. Li leaves Beijing to study immunology at the University of Iowa; a creative-writing class converts her and sets her on the path to becoming a writer. Like me and unlike Nabokov (whose story and wisdom pokes in and out of this narrative), Li spoke but never chose to write in her native language. She is often haunted by the many complex reasons for why she abandoned her mother tongue in her creative writing:

People often ask about my decision to write in English. The switch from one language to another feels natural to me, I reply, though that does not say much, just as one can hardly give a convincing explanation why someone’s hair turns gray on this day but not on the other, or why some birds fly south when the temperature drops. But these are inane analogies, used as excuses because I do not want to touch the heart of the matter. Yes, there is something unnatural, which I have refused to accept. Not that I write in a second language—there are always Nabokov and Conrad as references, and many of my contemporaries as well; nor that I impulsively gave up a reliable career for writing. It’s the absoluteness of my abandonment—with such determination that it is a kind of suicide.

And here one kind of haunting meets another: Just as ones proximity to suicide—whether sporadic failed attempts or sustained suicidal ideation—can forever unsettle a life, in Dear Friend the ghost of suicide never leaves the text. Li’s reflections on it make up the emotional core of this potent, beautifully disqueting meditation on mental illness, identity, and literature in all sorts of surprising ways. The memoir investigates, often in spirals, the source of Li’s depression, and it often lands back on language—what merges her various selves: the writer, the Chinese woman, the American woman, the wife, the daughter, the sibling, the friend, the teacher. The book ultimately grounds itself on one answer to its problems, and it comes in the form of her connection to other writers and literature. Nabokov, William Trevor, Philip Larkin, and Katherine Mansfield (who supplies the book’s title, from a journal entry Li stumbles on) are anchors as Li reads and writes her way out of mental illness.

Live on a diet of canonical Western literature as we have, and some clashes with identity and culture are inevitable. It’s interesting to consider how this might obstruct or fuel good writing. There is a way one can feel both more and less alone under such tutelage, but what if feeling alone is a constant anyway? When people ask me what my greatest fear is, I always reply that depression that will finally end me. And it’s not just my actual life of too many bills and too few naps and that great mess of students and friends and lovers and family. It’s that other realm that I cling to more deeply than my earthly life: the creative one. Nothing threatens my creativity, my reading and writing life, like depression. You want mental illness to come and go; you hope it’s not somehow built into your body and spirit, but sometimes you do wonder. And like Li often ruminates on her own relocation, I think about what leaving Iran post-revolution, at the start of the Iran-Iraq War, did to my life—would I have become a writer otherwise? Would I have been, as Li puts it, “calmer, less troubled, more sensible? Would I have stopped hiding, or become better at it?”

Li writes with a sort of unapproachable honesty, like someone who never accepts being liberated of those questions, those obligations, those burdens. I found myself sighing in relief as I read this book, as if I was coming properly unbound but never entirely. Even when Li circles back to the Tiananmen Square massacre, it’s not a loose end she’s tying; as with the 1979 Iranian Revolution, it’s in everything I write in ways I don’t seek to control. Only occasionally do the schematics of the book disrupt in artificial ways—the jagged shifts in structure are not so much the issue as when narrative is interrupted sometimes threefold by multiple layers and projections of historical and literary analysis. I was less interested in her coterie of authors and their truly vibrant rendering than her own life. Similarly, I felt taxed at times by moves that read too defensively, like a disclamatory declaration early in the book that she hates the word “I.” She claims “it is a melodramatic word” and that “living is not an original business.” But another way to see this is that she wants it both ways—here comes the memoirist’s anxiety about indulgences and narcissism, instead of giving in to introspection as the real work of this very real art. Li is always self-conscious and self-reflective, so being self-conscious about self-consciousness seems somehow alien to the book. Authors, of course, want everything both ways, every way, so why not have it all in a slim yet sprawling book like this one, where anything and everything is possible? The anti-structure of this anti-memoir Li has created allows space for all sorts of things, but occasionally in these cases of clogged conscience we lose our steps and hers.

Still, Li is writing to save her own life, an instinct and practice I’ve done much time in. Some of the most heartbreaking revelations surround her mother, whose disregard and inadequacies are as remarkable as they are relatable. Li’s recollections of her military service before coming to America are also hard to forget. But as sentences turn themselves around in sequences, as entire sections obsess over a single question, as all sorts of anecdotes come out stunningly half-baked, it’s the discomfort here that I most love and trust. One would think a memoir about depression would be soaked in emotion, dark and purple and oozing. Not so in Li’s book—and often not so in my experience. “It is hard to feel in an adopted language, yet it is impossible to do that in my native language,” she says, often in several ways in several instances. Feelings are a big problem in this book, but they are also a big problem in the real experience of migration—an ultimate displacement of the body—and depression—an ultimate displacement of the mind. With Dear Friend, the dissociative dances reluctantly with normalcy—it skims the surface of appearing normal—and what you end up with is a dispatch from a barely unscathed cusp of emotional detonation.

In reading Li’s work this winter, I couldn’t help but forecast even more disaster for the two of us, for so many of us, for all of us in this country. With the dilemma of dual identity, of leaving one home for another, of never quite belonging here—no matter what accolades, jobs, friends, family make it seem like—the pain is a constant. Now add to it this climate where I am back to an old childhood fear—could I ever be an American?—and most days I feel like every side of my hyphenated identity is being melted down and frozen over and over, always deformed in new ways. While I’m resistant to filtering everything past and present and future from the lens of our current American dictatorship, I have to admit the context makes a book like this even more vital. One might consider Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life a raw experiment from an otherwise disciplined author who doesn’t do messes, but the willful lack of control, the naked humanity, the willingness to explore every taboo of the psyche, is a peak from which Li most likely can’t climb down. This is a memoir of a breakthrough of mind and body, art and career even. The only dilemma of a rocky masterpiece like this is what next, how next? Where does one go next when you’ve given it your all? Survival means surprise, always—nothing ever quite goes as planned if you are invested in the world of the living, a fact depression forgets for you—and my suspicion is that Yiyun Li will continue surprising us, just as I hope our wounded and confused civilization will.