Enjoy access to our current issue! For full access to our entire archive subscribe now

The Madonnas of Librino

In Sicily, a hardscrabble neighborhood is transformed into a veneration of its mothers.

Here is a story from an ill-reputed Sicilian quartiere called Librino. This is neither the Corleone of Totò Riina nor the Palermo of the Mafia wars nor even the Gomorrah of the Savastano gang. Librino is a large suburb of Catania, on Sicily’s eastern coast, wedged between Mount Etna and the Mediterranean Sea. Conceived by an architectural genius but poorly built, it is home to Sicilians driven out of the historic center by gentrification. The result is a mixed neighborhood with made men of old Mafia clans lounging about and territories run by drug dealers with twitchy Dobermans; where the flowerbeds are overrun with weeds, and kids train horses to gallop down the boulevards, preparing them for illegal street races where the Mafia controls the betting. But Librino is also home to thousands of families who simply want to put the neighborhood’s grim reputation behind them.

Here, more than twenty years ago, a strange man arrived: Antonio Presti, heir to a fortune his father had built in the construction industry. The family lived in Messina, on the north Sicilian coast. In the early 1980s, after inheriting his father’s cement factory, Antonio sold the business to avoid potential entanglement with political corruption and the Mafia (nonnegotiable agreements, to be precise, that applied to anyone involved in construction or public-utilities contracts). As he did so, he transformed himself into a patron of the arts.

His first public art project was the Fiumara d’Arte, or “Seasonal Riverbed of Art,” which grew out of his commissioning a sculpture on Messina’s coast. (A fiumara is a distinctively southern Italian feature, strewn with rocks and dry all year except for intense occassional flooding.) For the next twenty years, Presti would commission numerous monumental sculptures at various locations between the mountains and the sea, fulfilling his first vision of integrating art with nature.

In the late 1990s, Presti set his sights on Librino with an ambition to reimagine the neighborhood as an open-air museum. He knew of its troubled history, but he could also see its potential. “Nobody had anything good to say about the place,” he recalls. “But I wanted to restore dignity and pride to Librino’s people.” He was determined to make something important happen there, an impulse that felt not unlike accepting a challenge or a bet.

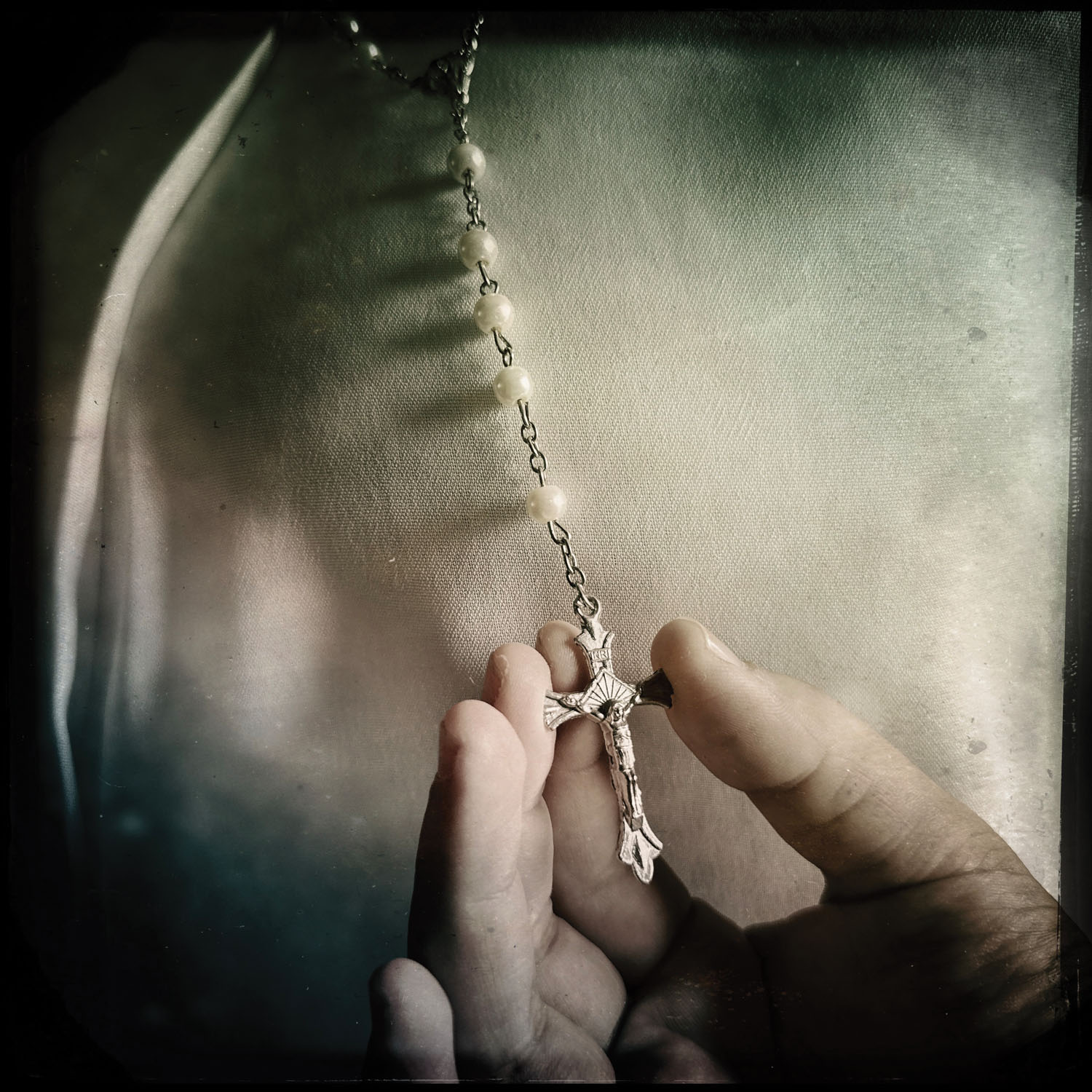

He began by inviting poets and writers—from Paco Ignacio Taibo II to Jonathan Coe—to read at schools and in the streets. Beginning in 2006, he had a portion of the gray highway viaduct that bisects Librino painted Yves Klein blue. He then asked thousands of school children from around Sicily to make ceramic tiles that would decorate it with figures and scenes that told the story of Sicily while paying homage to the figure of the Great Mother, an ancestral myth of Mediterranean civilizations. This was the nucleus of his idea for depicting the women of Librino as Madonnas, natural heirs of the Great Mother.

In 2021, he invited photographer Lynn Johnson to photograph the women of Librino in order to install their likenesses on the viaduct’s north side. Johnson received the invitation through an email from friend and editor for National Geographic Italy, Marco Pinna. “I didn’t even know where Librino was,” Johnson recalls. “I Googled it and read that it was like the Bronx of Sicily. So I said yes.”

Presti persuaded about forty women to meet with Johnson and sit for her, more than half of whom sat for portraits. Johnson traveled to Sicily several times over the course of three years, slowly earning their trust along the way. Among her subjects, Johnson met the daughter of a Mafia boss, but mostly they were housewives, shop assistants, a seamstress, and so on.

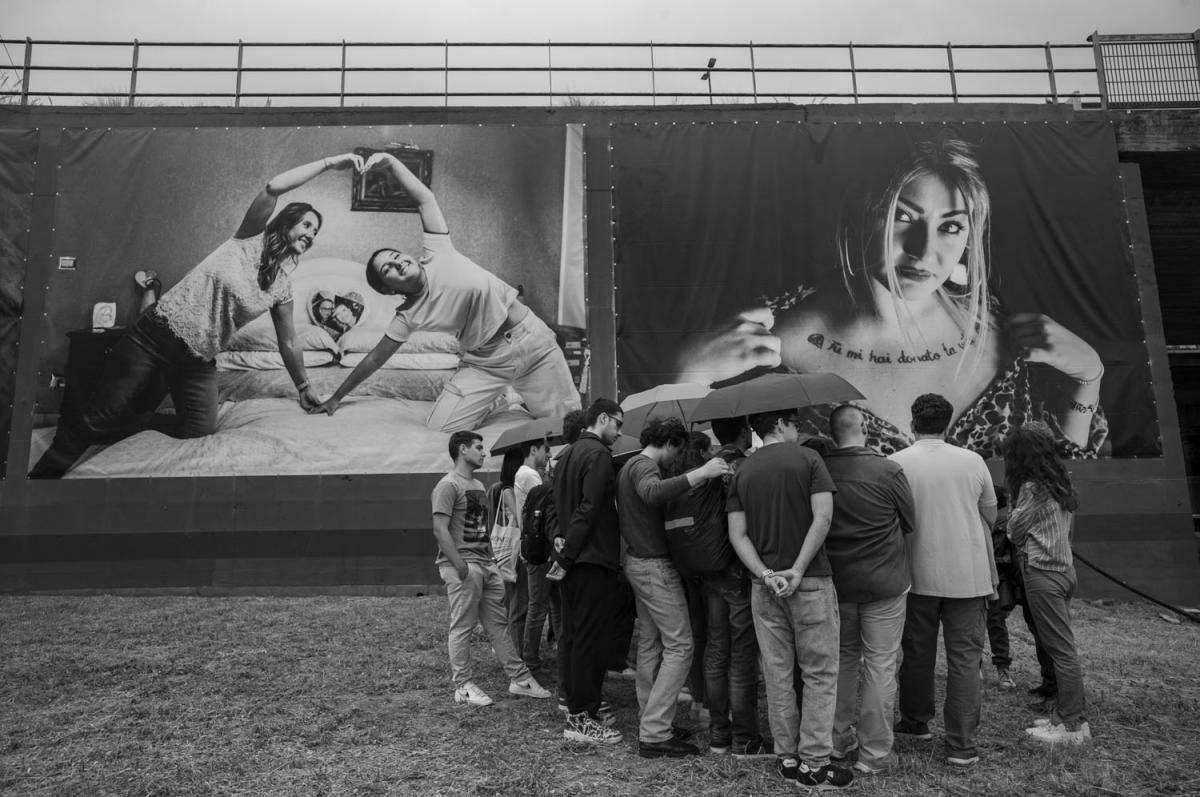

The result is a gallery of photographs, each one measuring more than twenty feet wide and sixteen feet tall, complemented by images projected onto nearby buildings. The women take great pride in seeing themselves there. They see themselves as beautiful. Their children regard them with a sense of importance. Their men have even complained to Presti because now they, too, want to be photographed.

Making men envious of women—especially where the birth of a son is hailed with fireworks in the street and blue balloons released into the sky—is a powerful blow to the chauvinist culture that nurtures the Mafia. The Sicilian writer Gesualdo Bufalino wrote that it takes an army of elementary-school teachers to defeat the Mafia. But a great photographer doesn’t hurt.

“In the periphery,” says Presti, using the term for the seedy outskirts of major cities, “you need to work with mothers if you want to reach children. Just sending them to school isn’t enough. And some of these women have lived or are still living through genuine tragedies—their husbands, fathers, brothers are either serving time or they’ve been murdered.” Some of Johnson’s subjects openly acknowledged their men’s connections with the Mafia; others were more reticent. Some refused even to admit that their husbands were in prison. Johnson says: “I asked one woman, ‘When is your husband coming home?’ She replied, ‘In one or two years.’ Not a word more.”

“These women carry the weight of their families in a society that is profoundly diseased in its consciousness,” Presti says. “I wanted them to feel the full sacrality of their roles as mothers, elevating their images on a wall that now resembles an altar.”

The project was unveiled in a public ceremony last May, with a crowd of thousands attending. “We’ve become works of art,” marveled Jessica Lamburi, mother to her nine-year-old daughter. In her portrait, you can see the tattoo that runs across her chest—you gave me life, flanked by stylized diamonds—which she dedicated to her mother, who carries its correlate on her own body: you gave me a reason to live. Jessica was born and grew up in Librino. “As a kid, coming home from school, I’d have to walk past drug dealers. That was normal for me. Now the place has been cleaned up, some order has been established. The dealers may still be around, but they don’t show their faces in broad daylight. All the same, I’ve never been ashamed to live here.”

Designed in 1971 by Japanese architect Kenzo Tange—the visionary behind the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum—Librino was originally conceived as a model community, complete with parks, museums, theaters, and even an artificial lake for water sports. Today, with a population of 70,000, neglect and private speculation have turned it into a patchwork of dignified apartment blocks and dilapidated public housing. Part bedroom community, part ghetto, it has no movie theater, no bookstore, not even a restaurant. Built three miles from the center of Catania and adjacent to an airport used by 12 million travelers a year, it remains such a marginalized place that it isn’t even included on the city’s official tourist map displayed on Via Etnea, Catania’s main promenade.

Presti, whom many respectfully call “Maestro,” has earned lasting gratitude for his commitment to this community. “Politicians show up only during campaign season, handing out grocery bags and cell phone credit top-ups—twenty or thirty euros to buy a whole family’s vote,” says Paolo Romania, a staff member at the Antonio Presti Foundation.

Disillusioned by politics, many of Librino’s mothers have invested genuine hope in the idea that Presti’s projects might actually improve their children’s future. “Here, girls become mothers at fifteen; by forty, they’re already grandmothers,” laughs Katia Paradiso, a seamstress and mother of two, speaking frankly about the difficulty of growing up in such a tough neighborhood. “When I was a girl, I enrolled at the Art Institute, in central Catania, with classmates who were the children of doctors, judges, and professionals. When they asked where I lived, I’d say, ‘Near the airport.’ If I’d said Librino, they would have judged me. It has a terrible reputation. Some of my children’s teachers confided to me that when they found out they’d been assigned to Librino, they wept.” But Paradiso defends her home. “I once saw a girl being beaten in the middle of the street in downtown Catania, and no one lifted a finger. Here, if your car breaks down, you just raise your hand and people run to help.”

Lino Secchi, former principal of the Campanella-Sturzo Institute (which has a student body of 900, from preschool to middle school), recalls that when Presti arrived more than twenty years ago, “people wanted him to fix the sewers, to bring streetlights. They grumbled: ‘He says he’s bringing beauty, but you can’t eat beauty.’” In the years since, however, the public art has become a cherished fixture. “In the school playground, workers lay down synthetic grass in the morning, and someone comes to steal it that same night,” says Paradiso. “But the tiles on the viaduct wall have been there for years, as pristine as the first day.” After the portraits were unveiled, Paradiso assured Presti that they’d be just as safe. “Don’t worry about maintaining the photos,” she told him. “No one will deface them. We’ll stand guard over the Madonnas ourselves.”

Like all the other mothers who sat for Johnson, Teresa Guglielmino, known by friends and neighbors as Cettina, was asked to choose her favorite image from the session. Hers shows her with headphones on, singing next to her laundry on the clothesline. “Ever since I was little, I’ve loved singing and dancing. I wanted to go to a music school, but my father forbade it.”

The daughter of a shopkeeper, Cettina lived with a brutally authoritarian parent until she married at twenty-nine. “He sometimes hit us,” she says. “My mother was submissive; she lived in fear. What should she have done? Report him? That would have been a disgrace. I couldn’t rebel either. I was attending vocational school with both boys and girls, and my father didn’t like that. After a year, he made me drop out. I took a few training courses to learn a trade, but he believed only men should work, not women. So I returned home.”

Her story could have ended tragically. “The mind hangs by a hair,” she says, recalling the time when, at twenty-two, she attempted suicide by overdosing on blood-pressure pills. “But the Lord saved me.” Now a mother of two sons, she says she’s proud to be one of the Madonnas. “It’s a word with a beautiful ring to it—Madonna,” Cettina said. “It feels good to hear it, to see yourself up there on the wall.”

“These women have changed the way they see themselves,” Presti insists. “Before, when they looked out their windows, all they saw was miles of bare concrete wall.”

Alessandra Galeano, a widow and mother of four daughters, agrees. “Librino was a dull place,” she says. “Antonio brought light and color to it, and he gave us the sense of being someone.”

As Presti puts it: “When what you see of the world changes, your life changes with it.”

Among the twenty-three massive portraits lined up along Librino’s viaduct—and another twenty-seven installed in five-foot squares on the overpass parapet—only one features a man: the husband of Gaia Impegnoso, mother of two with a third child on the way. “You can feel the trust in that photo,” Impegnoso says of her group portrait. “It’s as if my whole family is leaning on me.” A tattoo curls along her shoulder and arm: a bright red thread connects us for good, it can’t be seen, but it’s understood.

When she was young, Carmen Brancato worked in a bakery, then in a cleaning-supplies shop, and later as a preschool assistant. After getting married, she chose to devote herself entirely to her family. “I feel very close to little ones—and not just my own. There’s always a special magic between children and me.” Of her balcony, she says: “That’s my little corner of heaven. When my husband saw my image on the wall, he asked me, ‘Why aren’t the kids in it?’ And I told him, ‘Sometimes, it’s just nice to think about yourself.’”

While still in middle school, Lidia Arena won a poetry contest arranged by Antonio Presti. “My neighborhood is beautiful / my neighborhood is grim” she wrote of Librino. The award drew particular notice because Lidia is the daughter of Giovanni Arena, a notorious Catania Mafia boss who spent nearly two decades on Italy’s most-wanted list until his capture in Librino in 2011. He was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Two years ago, Alessandra Galeano’s husband died in his sleep, lying beside her. “At one in the morning, our whole world collapsed. He had always treated me like a queen. He was a truck driver and made sure we had everything we needed. My life consisted of waking up in the morning, making breakfast, walking the girls to school, doing the shopping, cooking. When he died, I thought, I can’t go on. I didn’t leave the house for a year. But now I work—I clean house in four different places, bring home our daily bread, raise my daughters, and I feel proud.” She pauses, then adds: “I believe that, with or without a man by our side, we are the Great Mothers. We are the Madonnas of Librino.”

Lynn Johnson is a regular contributor to National Geographic magazine. She was a Knight Fellow at Ohio University and teaches at the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University.

Antony Shugaar is a writer and translator of Italian and French works. He has translated dozens of articles for The New York Review of Books and close to forty novels for Europa Editions. He has translated many novels that were awarded Italy’s highest literary award, the Strega Prize. He is...