Plastic Futures

“A stomach…plastic pollution mimicking pink quartz, garnet, turquoise, jade, sapphire, topaz, rose quartz, pink tourmaline, ruby,” writes British photographer Mandy Barker in her research notebooks for her series STILL (FFS). Alongside these words is a black pane framing what looks like a gemstone, green hues with mottled edges. The thing could be nestled against black fabric or suspended in deep space, a mineral fragment hurtling through time.

As Barker’s words suggest, though, the object’s provenance is more complicated. It is one of dozens of plastic fragments extracted by scientists from the stomach of a Flesh-footed Shearwater chick from Lord Howe Island, a nub of volcanic rock in the Tasman Sea.

When I visited the island in 2012, the shearwaters had not yet become synonymous with the global plastic crisis. Each evening, my young daughter, partner, and I—oblivious to the birds’ dilemma—went to Ned’s Beach to watch the birds arrive onshore after a day spent at sea, foraging for their chicks. The island hosts the world’s largest Flesh-footed Shearwater (Ardenna carneipes) population, with more than thirty thousand burrows and over twenty-two thousand breeding pairs.

The shearwaters appeared around dusk, emerging from across the low-lit sea, here one, there another, muted-brown plumage and loping wingbeats, each carving a route back to its burrow dug into the sandy forest floor, amid banyan trees with vast buttressed trunks and dangling aerial roots. They arced from water to land, dark shapes against a darkening sky, discrete, silent, disappearing among the vegetation.

We watched until night fell. Walked home through the forest by the light of headlamps. Here, the birds shifted from distant spectacle to something quite other. To find their burrows, they crashed through the forest canopy, a mix of skill, daring, and clumsiness. The night filled with the sound of foliage parting and shredding, birds dropping through branches, careering between trunks. One landed just ahead of us by the roadside. Another, perhaps disorientated by our swaying lights, collided with my shoulder.

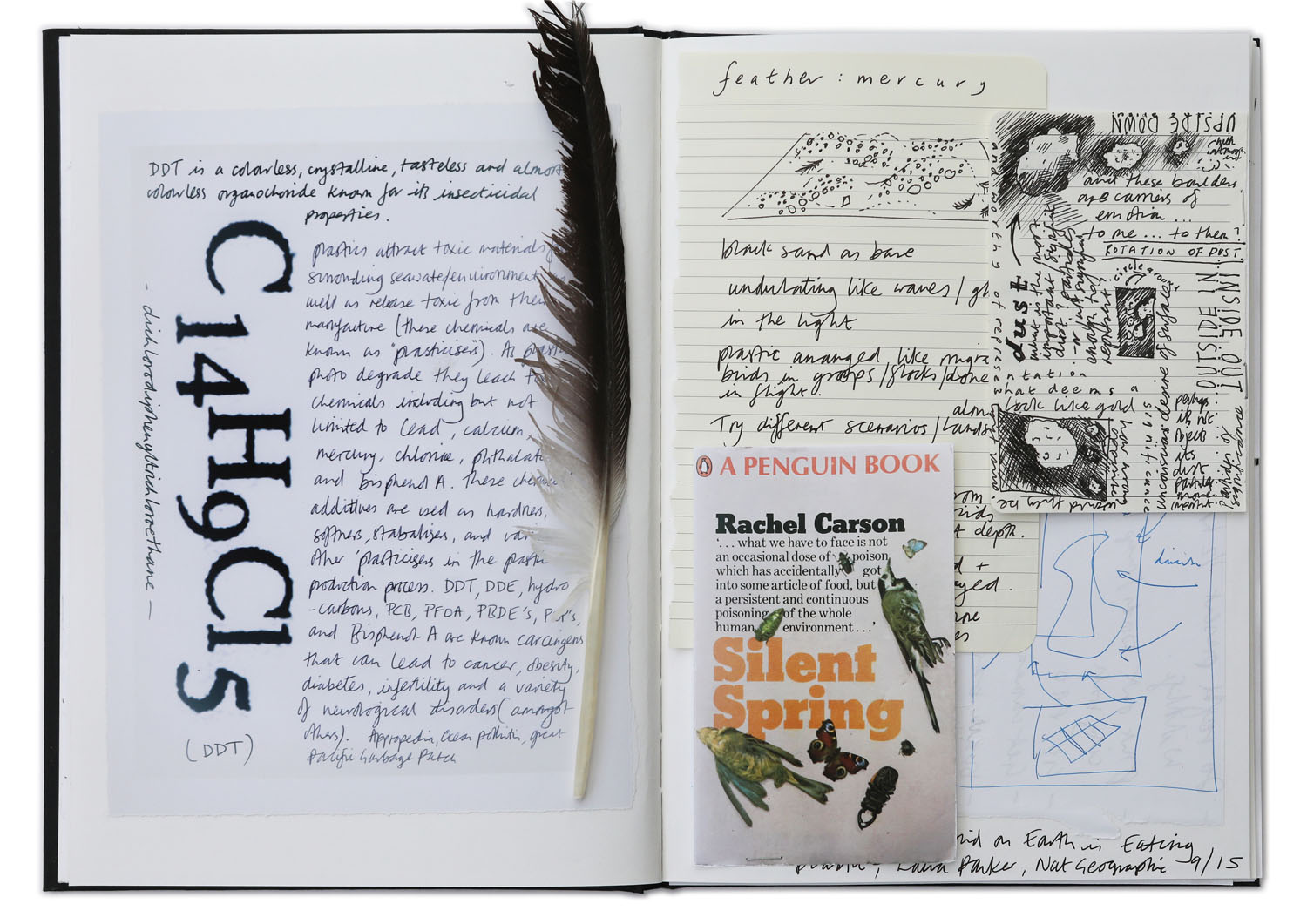

In this dark forest, without us knowing, a tragedy was unfolding—adult birds disgorging pieces of plastic down their chicks’ throats. The consequences are dire, and it is these consequences Mandy Barker bears witness to in STILL (FFS).

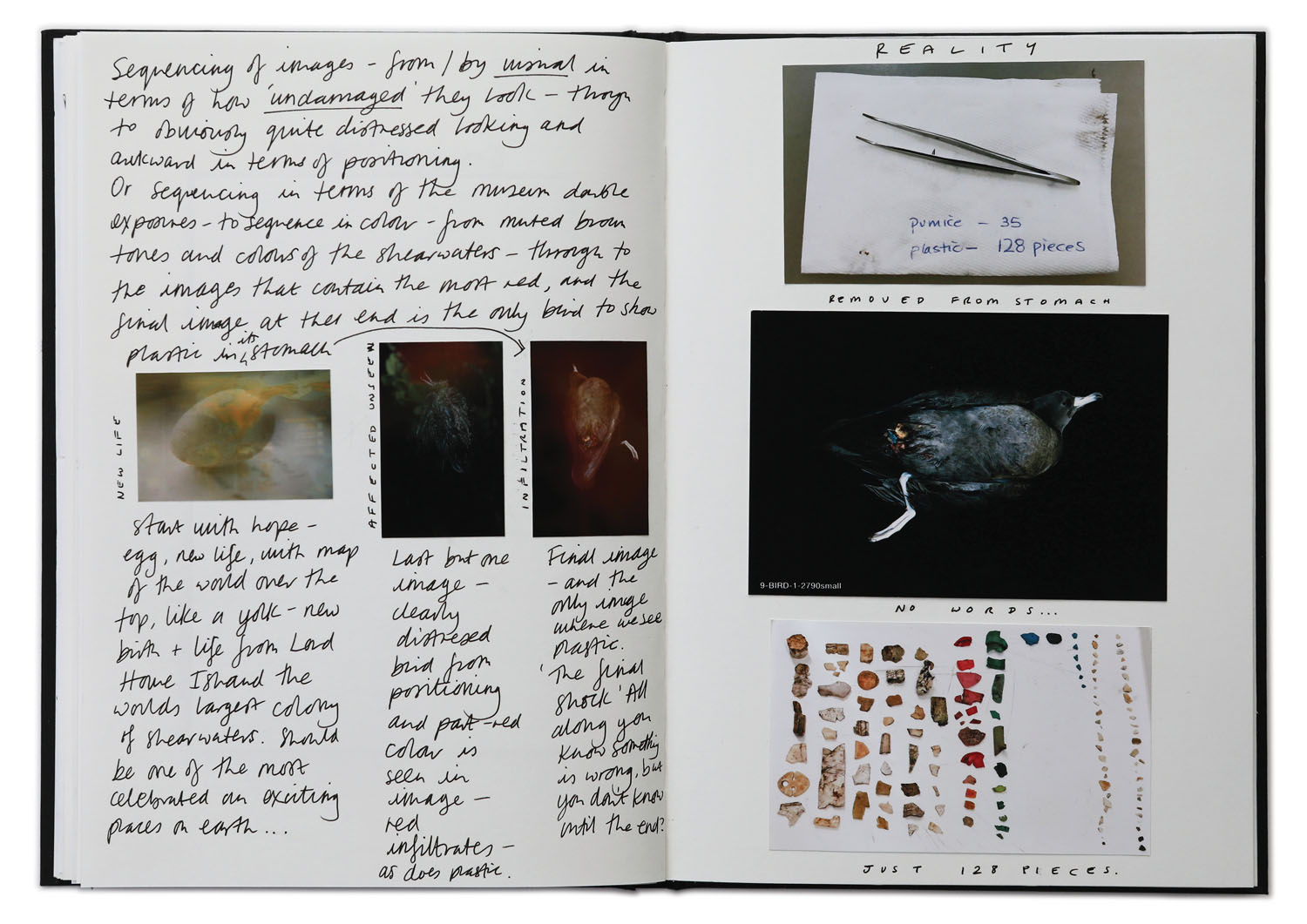

For her first three days on the island, Barker told me, she wasn’t sure how to respond to the dead and dying birds. She stood in the lab watching the scientists at work. “I was amazed at what could come from a bird’s stomach.” Silence fell as each bird was cut open. “No one spoke. There was just the chinking sound of each piece of plastic being placed in a petri dish. It was very respectful. The birds kept their dignity in death. And I wanted to capture that dignity too.”

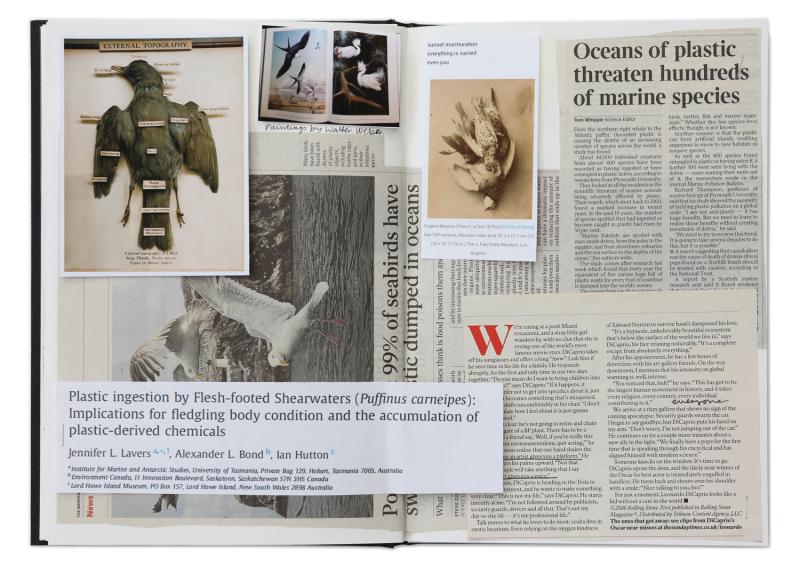

Barker has been photographing marine debris for sixteen years, drawn to this subject by escalating amounts of waste along her local Yorkshire coastline. Her work traces something of plastic’s ubiquity, its refusal to break down or to disappear. An early suite of photographs, Shoal, shows galaxies of plastic fragments suspended against black, collected during the Japanese Tsunami Debris Expedition in 2012, which sailed across the tsunami debris field in the North Pacific Ocean: A tatami mat, fishing objects, petrol container, pieces of flooring; a toy gun found on the shoreline of the Fukushima Prefecture replicated to resemble a shoal of fish; or a great miscellany of colorful everyday objects—toothbrushes, suitcase handles, shoes, rubber gloves, coat hangers, a child’s ball.

Despite the grim subject, her imagery is seductive, puzzling, lyrical. In another series, a drift of synthetic orange rope with frayed ends becomes anemone or polyp-like. A torn blue plastic bag grows trailing jellyfish tendrils. A cloud of artificial flowers resembles fabric design. In her recent book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Imperfections, scraps of synthetic fast fashion found in rockpools are intricately cut to resemble delicate seaweeds. With STILL, Barker’s gaze shifts from plastic to the creatures whose lives it disrupts. By proxy, the birds also hint at human lives. As nanoplastics infiltrate human blood, hearts, kidneys, brains, placenta, and semen, our bodies, too, are interwoven with the plastics that surround us.

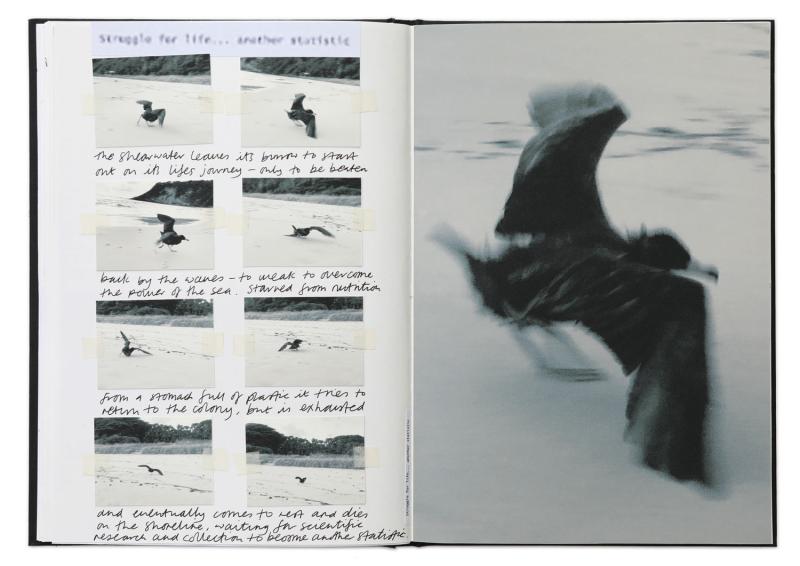

Another page from her notebooks shows a sequence of photographs tracing movements of a young bird on the shoreline. In a world before plastic, a shearwater’s lifecycle went like this: ninety days spent inside the burrow, plied with food until its bodyweight is up to a third bigger than that of its parents, then crossing from forest to shore, taking flight. Shearwaters are pelagic birds, living mostly on the open ocean, like the albatross. Once fledged, the young shearwater spends five to seven years without touching land, migrating to the North Pacific. Occasionally it will “raft” with other birds to feed, but spends most of its time alone, diving for fish and small squid, filtering salt from its bloodstream through salt glands, resting on the sea. After five or so years, it returns to its burrow to breed, landing within meters of the burrow entrance whose location is imprinted in memory through sensory traces. Shearwaters carry intricate maps of ocean and land based on scent.

Barker’s notebook charts what should be the young bird’s first moment of flight. Instead, its stomach is so laden with plastic, its body so malnourished and compromised by toxic chemicals residing in the plastic and heavy metals on its surface, leeching into blood, tissue, feathers, that it struggles to become airborne. The photographs capture moments in this sequence—the bird staggering, wings spread, keeling to one side, like an Eadweard Muybridge study of motion inverted, stuttering to a close.

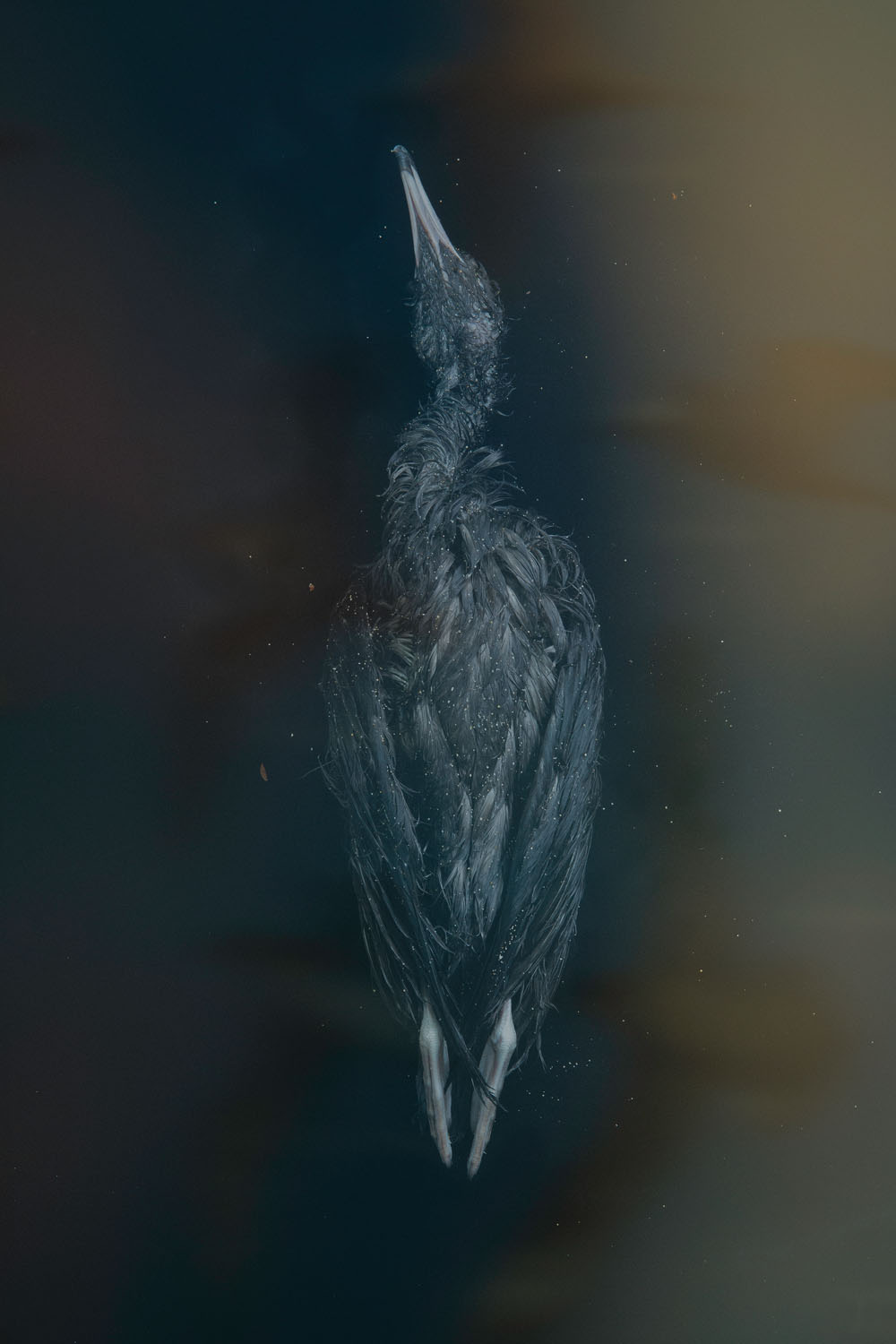

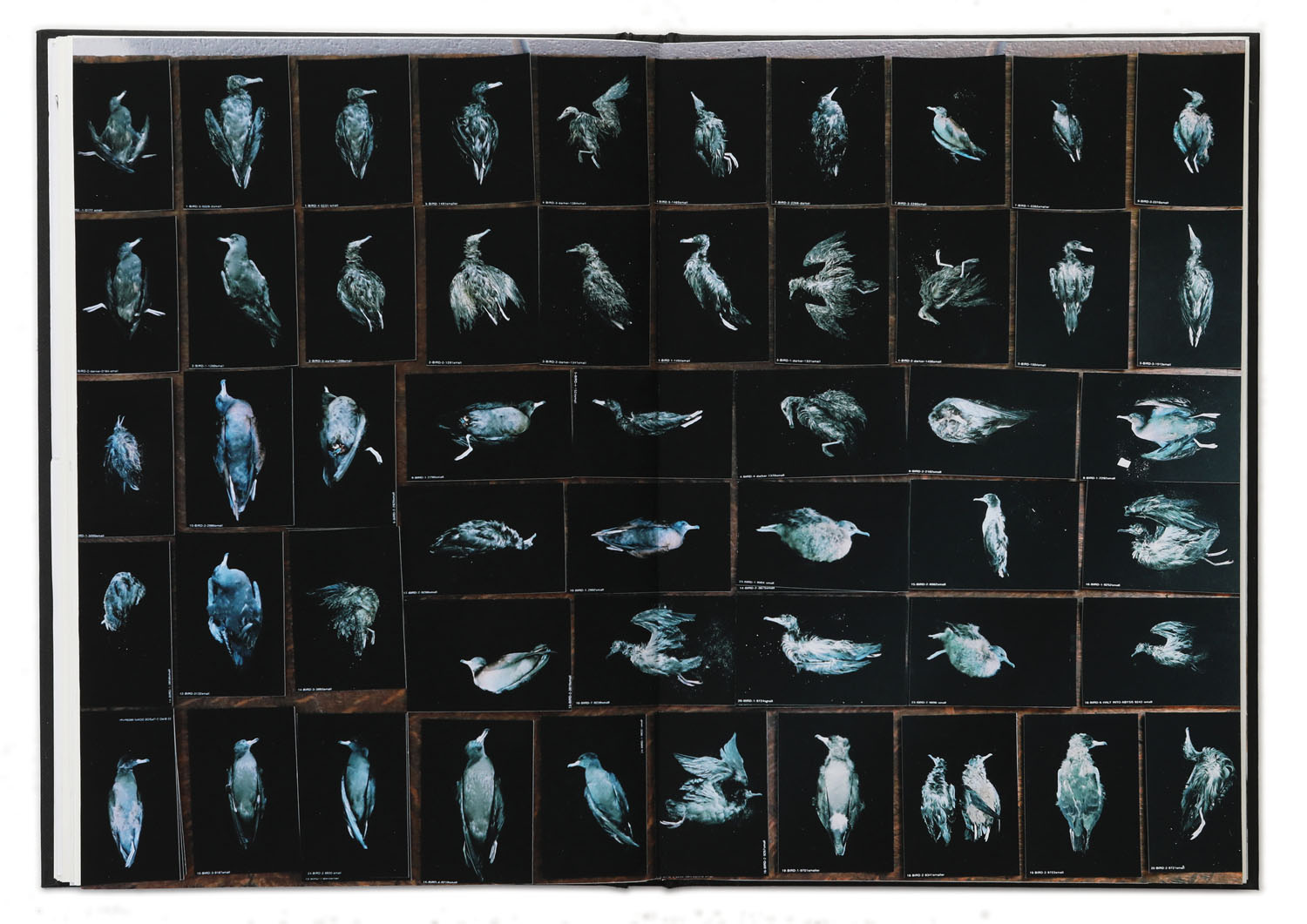

As I write this essay, I find myself skirting STILL’s central images: the harrowing bird portraits with their staccato titles: Wing, Sky, Flight, Soar, Rest, Sleep, Plead, Reveal. They represent all the dead birds collected during Barker’s two-week stay on the island. Each morning, the scientists rose before dawn to collect shearwater carcasses before honeymooning couples and other tourists began roaming the beaches. The island is beautiful. Two volcanic peaks of black basalt tipped with cloud forest; a lagoon harboring Australia’s southernmost coral reef, far from the tropics but sustained by warm currents; endemic birds and plants; local kentia palms hissing in sea winds.

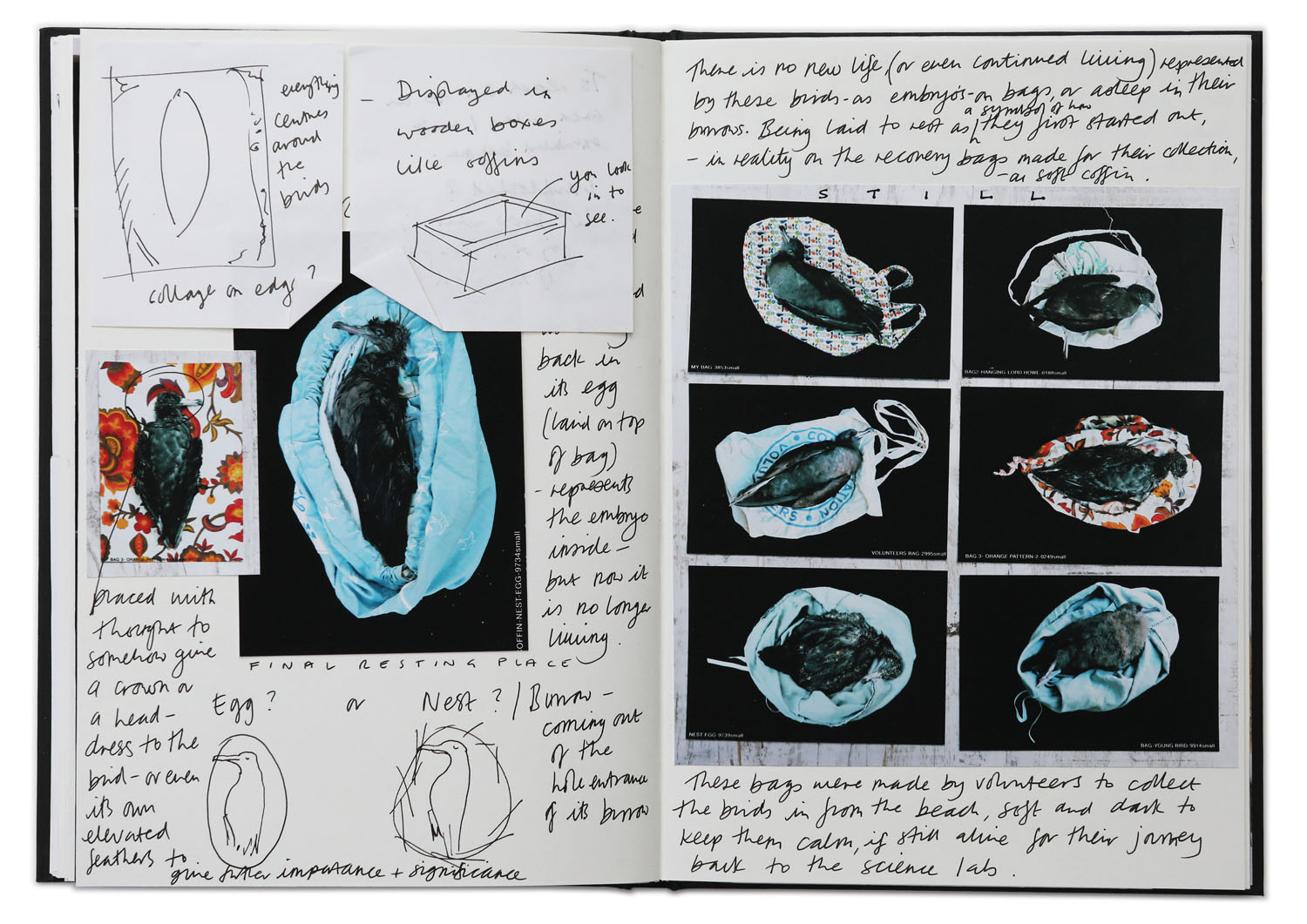

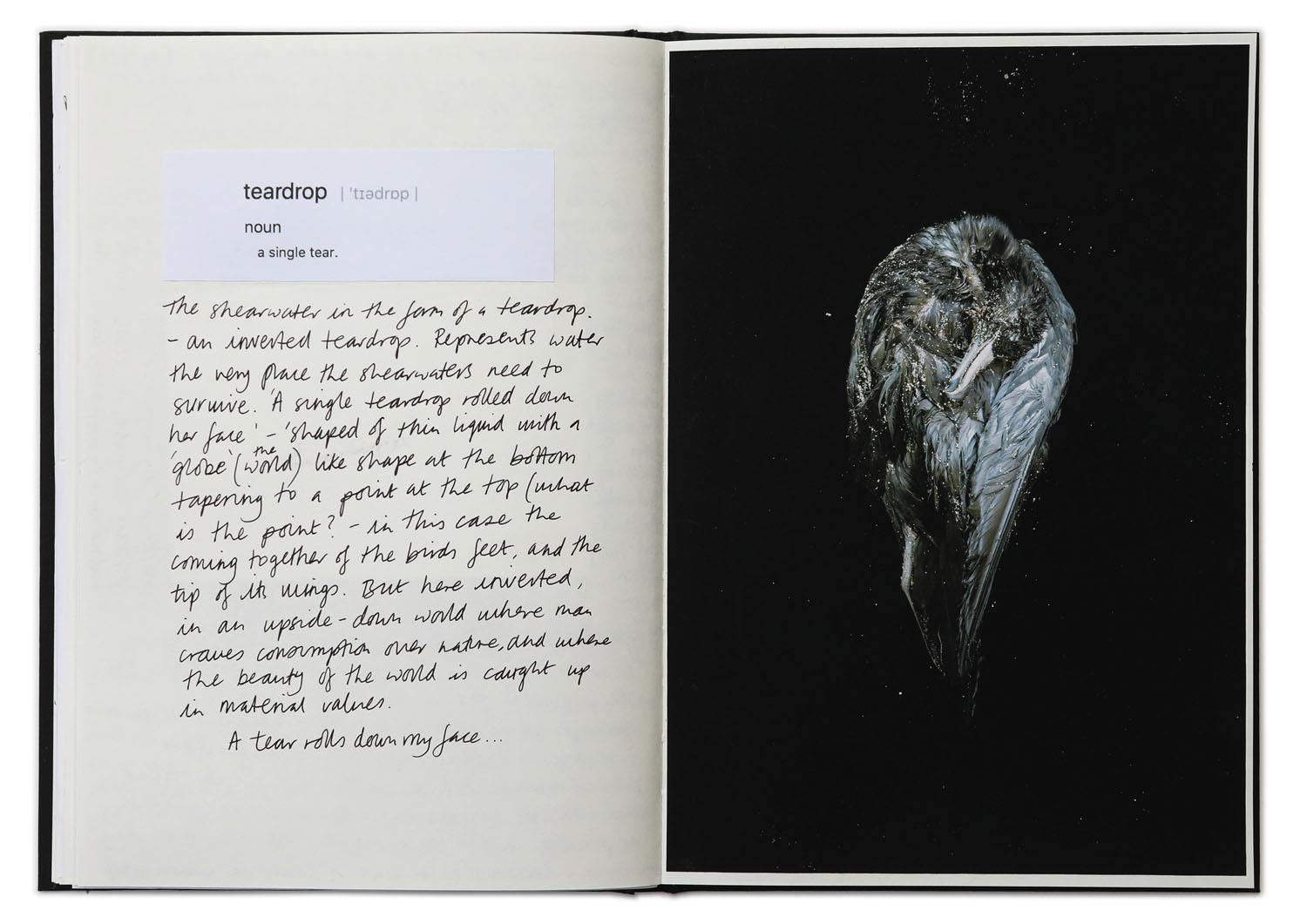

Barker helped collect the bodies, placing them in handmade cloth bags donated by volunteers. She photographed each bird against a piece of black velvet cloth, which she carries everywhere, laid outside the lab before the scientists began their work. Each pose is as faithful as possible to that in which the bird died. Beneath the blackness hovers other images, upon which the birds are superimposed—subdued scraps of sky or water, the Milky Way, edges of foliage, floral fabric of the carry bags or “soft coffins,” basalt, reflections in the lab window. “I wanted to think about the birds interacting with the world around them, going about their lives. I didn’t want the images to be too shocking.” There are no incised stomachs, apart from the final bird, wounded on the shoreline, innards exposed.

The illusion is that the birds are still almost animate—plummeting, soaring, diving, resting—but all the while we know they are dead. The series hints at eighteenth- and nineteenth-century specimen collections, plants and animals arranged in trays or boxes. In the heyday of natural-history collecting—with its practices of discovery, preservation, and naming inextricably linked with colonialism and expanding empires—the world seemed an abundant place, filled with limitless curiosities. Here it is a shrinking world, not a corner of the world’s oceans, or our own bodies, untouched by plastic. And it is undoubtedly a world of suffering and wasted life—caused by our own actions and choices—no matter how much the birds retain their dignity.

For Barker the question is always about change and action. She aims to get under the skin of the unwitting violence enacted upon these creatures and the complicated issue of responsibility. Fragments tweezered from within the birds, brought into sharp relief by her long exposures, are a reminder that they could belong to any one of us, a balloon clasp threaded with blue balloon scraps, a pale-yellow plastic bow you’d find on a child’s hair clip, a white die.

Mandy Barker is an internationally acclaimed British photographer celebrated for her work involving marine plastic debris. Barker was the recipient of the 2023 International Understanding Through Photography Award, the Royal Photographic Society Environmental Bursary, and a National Geographic Society grant, among others.