Enjoy access to our current issue! For full access to our entire archive subscribe now

The Hottest Border

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

There is no mistaking those paw prints. They’re from a bear—no doubt about it. Tom and his patrol partner, Kersti, often spot the animal on the monitor during their night shifts. From their command center in Piusa, in southern Estonia, border police watch footage from around three hundred cameras placed along the seventy-mile stretch of border. They see the massive creatures rise up on their hind legs and swipe furiously at the steel fence. “Sometimes they manage to bend it,” Tom tells me. “Other times, they get tangled in the barbed wire—we see on the screen how painful it is for them to break free. It’s heartbreaking.” At twenty-eight, he’s already a captain. His thick glasses and handlebar mustache remind me of the young East Germans before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

We’re in a Volkswagen SUV heading south through a snow-covered landscape, sleet lashing at the windows. The road hugs a gleaming border fence—it was hastily put up after February 2022, as fear spread like a shockwave across the Baltic states following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This place is a fault line of geography and misfortune, where old fears have suddenly stirred back to life.

To our left, just beyond the sixteen-foot fence, lies the Russian forest. We see markers painted the white, blue, and red of the Russian flag alongside skull-and-crossbones posts and signs in Cyrillic. They mark the beginning of a space that stretches all the way to the Pacific, an empire stirring once again, and with a hunger for vengeance. To our right is a strip of deforested land and abandoned fields. Then, like a great wall, the Estonian forest, with its towering birch trees, Scots pine, and alder. We are at the very edge of what we call the West, a word that grows less certain and more ambiguous with each passing day.

Estonia’s army guards this border vigilantly, eyes fixed on the tree line, day and night. This is where plans for the next European front are being drawn—a two-hundred-mile line running north to the Baltic Sea, slicing through the expanse of Lake Peipus and tracing the course of the Narva River. Those who believe that Russian President Vladimir Putin intends to reclaim his country’s storied past have marked the line in red to indicate that this is where he’ll start, regardless of NATO’s Article 5, which stipulates that an attack on one member of the alliance triggers a response by all.

Kersti, a lieutenant in her thirties, has long copper hair and nails painted black and blue—two of three colors of the Estonian flag. As she drives, I point out that their troublesome Russian bears feel like a fitting metaphor for the Russian Bear itself, now more likely to arrive not on four legs but with T-90 tanks and hypersonic missiles. She laughs—she hadn’t thought of that. “Still coming from the same place,” she says, tapping a nail against her window. “Estonia has been invaded forty-four times in a thousand years. Always from the east—never the other way around. Same with the bears. I don’t know why, but only their bears cross over. Sometimes whole families come to eat our apples.” She gestures at the woods beyond the fence. “Look at their forest—it’s a mess. They cut without care or a real plan. Ours is different. Here, you’re not allowed to cut more than eight thousand cubic feet per hectare per year.”

Tom comes alive when the conversation turns to animals and nature. He’s more like a gamekeeper than a border guard. His phone is full of pictures of birds he’s spotted on patrol. As he scrolls through them, he tells me about the Russian vodka and cigarette smugglers. The Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (FSB) sends them to test Estonia’s surveillance net or to map out vulnerable sites. He recalls how, at the start of the war in Ukraine, their elite unit in Piusa stopped exchanging nods with the Russian guards across the fence. A small but meaningful gesture.

When we reach a break in the fence, Tom asks Kersti to stop the jeep. “My National Geographic moment,” he says. We step out of the car, with Ärni—the Belgian shepherd Kersti trained to detect Russians, somehow without crossing onto enemy territory—trotting close behind us.

“This is where the border juts east for a few miles,” Tom says. “Before the war, we were in talks with Moscow to simplify it—to draw a cleaner line and trade it for another strip of land. But that ship has sailed. The upshot is that this has become the only point where animals can safely cross.” Two deer appear almost on cue, standing stock still at the tree line at the edge of the Estonian military zone. “I bet they’ve escaped from Russia,” Kersti says. Tom shakes his head and explains that Estonian deer know this is their only way out. “We see it on the monitors—lynxes have figured out they can chase them toward the fence, trap them there, and tear them to pieces. So the deer hole up in this area, ready in case they need to dash off to Russia. But then they come back.”

I tell Tom he should write a geopolitical bestiary. I recount my trip to Russia in the summer of 2023, when I made my way down the Volga from its source in the Valdai Hills, just over one hundred miles from where we now stand. I traversed four thousand miles in a month on the road, and in all that time I didn’t see a single wild animal, save for crows and a few flocks of migrating geese. It was eerie, as if the famous Russian wilderness had been stilled. Tom pulls off his fogged-up glasses and wipes frost from his red mustache with the sleeve of his camouflage jacket. “I wonder if animals sense the tensions among people,” he says. “Maybe they, too, hope for a freer world?”

I think of the Balkan wolves, fleeing the mortars as Yugoslavia went up in flames. They crossed the Italian border to take refuge in the Eastern Alps, where some remain to this day. And I think of storks, who have their own vision of Europe: In 2004, when tracing the eastern frontier of the newly expanded European Union, from Mohács in southern Hungary to here, by the Baltic Sea, the mayor of Ubl’a, a village in northeastern Slovakia, told me I was following “the stork route”—the path these birds take each spring from Africa to return to their nests. One such nest rested atop the pitched roof of the town hall. The only map in the mayor’s office was of stork migrations across eastern Europe, a flight path now uncannily similar to the boundaries of the new Iron Curtain—NATO’s eastern edge. Geopolitics ebbs and flows while the birds simply stay on course.

Perhaps it’s only a myth, born of the low, constant tremor that runs through the nerves of those who live on the border—but they say the storks no longer visit the farms of the five thousand or so Estonians who remain on the Russian side, in the Pskov region. “FSB agents don’t let them put prefab nests on utility poles like we do here,” Reín Jävelill tells me when we meet in Värska, on the southern shore of Lake Peipus, just a mile and a half from the border. “They’re afraid someone might use them to transmit radio signals.”

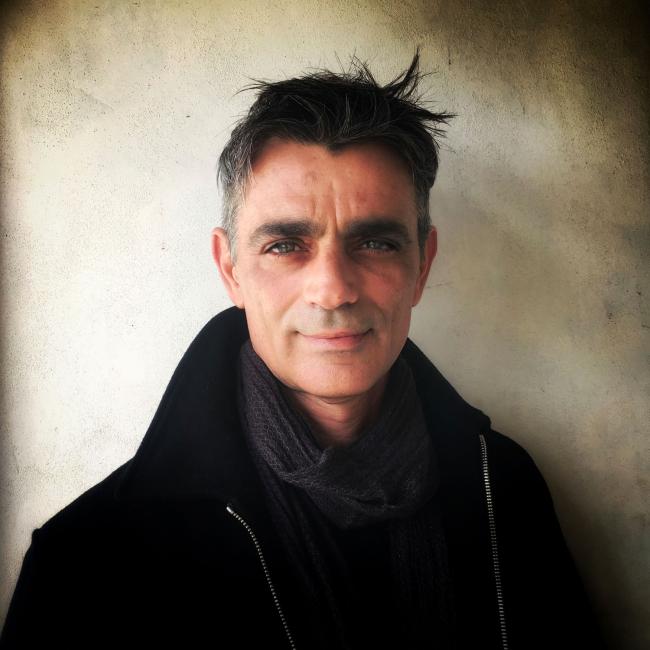

At fifty-eight, Reín still has a youthful face, but he is already the head of the elder council of the Setos—an ancient Finnic people whose Orthodox Christianity is laced with pagan and animist beliefs. He has the physical stature of a deeply rooted tree. His long, unkempt hair is partially gathered in a loose ponytail. Once a social-democratic member of parliament in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, he now devotes himself to the cultural survival of his dwindling community (between three thousand and four thousand Setos remain on this side of the border). Reín speaks of defending his tiny homeland from what he calls “the arrogant rulers of our time,” by which he means global superpowers as well as Estonia’s own government. He neither confirms nor denies that he is the heartthrob of the Seto women, as claimed by his friend, the spa manager at the local resort where I’m staying with my photographer and friend, Alessandro Cosmelli. But it may have helped him land the position of the Setos’ king in 2023 and 2024.

Every first Saturday in August, the Seto people choose a new monarch—an earthly regent for Peko, the fertility god who sleeps eternally in the Pskov Monastery of the Caves just across the border in Russia. Strength and charisma can help a candidate get elected, but what really matters—literally—is his ability to put together an exceptional female choir to sing his praises. On his first day, the monarch can ask for anything—Reín makes a sweeping gesture to indicate the full spectrum of pleasures available to a man in his position. Then, throughout the year, Peko appears to the new monarch in dreams and hands down the year’s political decree, which always includes: Defend the language.

In Estonia, language is an ideological obsession. “We were Russified under the czars,” Reín says. “And since 1991, Tallinn has tried to Estonianize us. They call us separatists because we defend our language. They suspect us of backing Putin because we’re Orthodox. But Estonia didn’t even exist before 1860.”

Reín believes the cultural erasure facing the Setos is foreshadowed by what is happening to Estonia’s Russian-speaking minority, which makes up roughly four hundred thousand of the country’s 1.37 million people. Most live around Tallinn and in the northeast, especially in the border city of Narva, where they form 97 percent of the population. Since the invasion of Ukraine, the government’s stance has hardened into outright Russophobia. Former Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, now High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and a vice president of the European Commission, helped lead the charge. Russian-language schools have been banned, with Russian now being treated as a foreign language like any other. Even in areas where Russian speakers are the vast majority, education must be conducted entirely in Estonian. It’s like banning German schools in South Tyrol. “It’s rash, hostile—and it will only deepen the divide,” Reín says.

Maybe it’s the looks and the words said or left unspoken of the people we meet, the farms falling into disrepair, the interference on our phones, or the feeling of being within striking distance of Russia, but that light further dramatizes the oppressive atmosphere on the deserted roads along the border. Invasion gray is a weathered pallor that drains life from these lands and sullies the snow. It’s an omen of hard times and ruin.

Meanwhile, Moscow has been accusing Estonia and Latvia of discriminating against Russian minorities. Putin has already used that pretext to justify his imperial aggression. “We saw it with Russophones in Ukraine, who no doubt underwent forced linguistic assimilation,” Reín warns.

Still, Reín understands the paranoia. Especially here, so close to the border, where emotions run high—anxiety, fatalism, a creeping sense of historical repetition. “Even the young feel it,” he says. “They talk about invasion as if their turn is up—not if, but when.” It’s a kind of collective déjà vu, a sense of dread passed down through generations. “People say the KGB left sleeper agents all over here,” Reín tells me. “And that some of the Estonians living across the border are informants for our side.”

Being here feels puzzling. At times, it’s like I’m in an imaginary place. But then I feel like I’m in the exact right place to grasp the mechanisms of this geopolitical gridlock that causes Estonia to remain stuck between imperial legacies: passed back and forth between the German Empire and czarist Russia, then between the Third Reich and Stalin’s USSR. On top of that, amid the chaos of Putin’s war and Trump’s presidency, it is caught up in tensions between Russia and the West, NATO and the European Union.

Inside this larger frame lies the fate of Setomaa, the motherland of the Setos. “A language needs people to speak it,” Reín says, his voice suddenly bleak. “But some of our villages are down to ten people. Everyone leaves. But what saddens us the most, more than the ever-present shadow of Russian aggression, which we’ve always lived with, is the collapse of a world order. Now all that remains is the law of the strongest. In a world like this, if you’re not big and strong, all you can do is put your hands up and surrender.” With that, Reín raises his own massive arms with an air of resigned frustration.

We spend several days tracing the edges of Reín’s severed realm: Two-thirds of the Seto ancestral lands lie on the Russian side, including Pechory, the old administrative center. Today, Obinitsa, a village of around 140 souls, is holding a festival to mark the first Sunday of Lent according to the Orthodox calendar. Young Seto women wear traditional long, cream-colored dresses in heavy, boiled wool and wrap their heads in muslin scarves stitched with flowers. Standing in the snow, they ladle borscht and serve plates of pancakes glazed with rosehip jam and birch syrup.

At Reín’s urging, they begin to sing the Seto leelo, a polyphonic a cappella-style song that has been named by UNESCO as an intangible cultural treasure. Kati, twenty-seven, sings lead, improvising verses that lament severed roots, creating a sound that recalls the sorrowful chants of some Sioux tribes. In the freezing cold, the singers’ breath merges into a single cloud of steam that thins out and disappears, reappearing a moment later, fully formed, as the singing ebbs and flows.

“My grandfather is buried in Tailovo, just two miles away, in Russia,” Kati tells me. “But my grandmother’s grave is here, in the village.” She runs the local museum of rural life. Her red cheeks glisten—from snow or tears, it’s hard to tell. One of the Setos’ oldest rites, she explains, is to bring food to the graves of loved ones on holy days. But since 2022, the border has hardened into a kind of cold permanence. The Setos are often suspected of spying and are targeted for lengthy interrogations by border officials when crossing into Russia. Reín’s own dead lie out of reach across that invisible wall, including his brother.

Until 1918, Setomaa—like the rest of Estonia—belonged to the Russian Empire. But in 1920, following Bolshevik Russia’s defeat in the War of Independence, it ceded a portion of the Pskov region—the entire ancestral land of the Setos—to Estonia. That border held until after World War II, when Stalin absorbed Estonia into the Soviet fold. The Estonian border became merely administrative, and Seto territory became whole again, but only under the illusion of internal unity within the Soviet regime. So when Estonia reclaimed its independence in 1991, the new Estonian state gave up Pskov—though neither Tallinn nor Moscow ever ratified the treaty.

Europe’s hottest border now bears the strain of unresolved claims. “The monastery at Pskov was the only one spared by Soviet atheist fury,” Kati tells me. “Because it was in Estonia, which the USSR saw as the gateway to Europe, a kind of showcase of the West to display behind glass. Putin often visits the monastery with his confessor, Tikhon—a former monk and now archimandrite [a priest in the Orthodox Church] in Pskov. People say Putin goes there because it’s right on the border, to intimidate us.”

There is a certain eerie light that envelops the landscape around us, especially in the afternoons. Cosmelli calls it “invasion gray.” Maybe it’s the looks and the words said or left unspoken of the people we meet, the farms falling into disrepair, the interference on our phones, or the feeling of being within striking distance of Russia, but that light further dramatizes the oppressive atmosphere on the deserted roads along the border. Invasion gray is a weathered pallor that drains life from these lands and sullies the snow. It’s an omen of hard times and ruin.

Koidula station was once a promise. When it opened in 2011, it embodied a vision of East meets West—a sleek, ambitious node for trade between Russia and Europe, particularly Germany. Ten lines of track, each fitted to Russia’s gauge, served trains heavy with fertilizer, liquified natural gas, grain. But when sanctions came in 2022, the rails were switched out to fit European gauges. Now the station lies mostly abandoned, a graveyard of locomotives devoured by rust and weeds. Only one line remains active for the odd local train carrying blue-collar workers, soldiers, and students to Võru or Tartu, in Estonia’s interior.

The desolation cuts deepest for those who watched Estonia claw its way out of Soviet rule. It managed to build a strong economy, a reputation as a global tech hub, and it became a leader in e-government—all within the span of a single generation, and thanks to an abundance of educated and creative young people. I remember a roaring Tallin, a veritable Silicon Valley, boasting the highest number of start-ups per capita in Europe—ten of which are valued at more than a billion dollars. But now Estonia seems to be transforming into a wartime front, its economy shifting to prioritize defense, cutting social services. Preparing for conflict, whatever the cost.

“Our relationship with Russia is like Israel’s with Hamas,” Martin Hurt, a former defense ministry advisor, told me in Tallinn before I headed southeast, by which he meant a total and radical incompatibility. “Russia is our enemy. A hundred percent. That much is clear. But they’re not the ones keeping us up at night. Our friends are. Our allies. We must prepare for the possibility that we’ll have to fight this one alone.” Then, looking me straight in the eye, he added, “We know Russia wants to kill us. So we’re preparing to cause them pain.”

Defense spending now swallows up 5.4 percent of Estonia’s GDP, exceeding the 5 percent called for by President Trump among NATO countries. The debt-to-GDP ratio has climbed to 23.6 percent. Energy, once piped in from the east, now arrives from Finland and Poland at a higher cost, slowing industrial output. Still, in February, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania disconnected from the Russian electrical grid and synchronized with Europe’s—a symbolic gesture, and an indictment against Estonia’s Soviet past.

Estonia then turned to the Scandinavian markets to compensate for the loss of Russian trade, but Sweden’s downturn dealt a heavy blow to Estonian exports. Inflation has since climbed—to 6.2 percent and counting—as the price of consumer goods and services skyrockets. In a country hailed for its digital fluency, where each citizen receives an electronic ID at birth and where 100 percent of government services are provided online, there’s been a jarring return to cash, which is often paid under the table in order to avoid taxes. A bowl of soup costs up to 15 euros, and many restaurants outside Tallinn or Tartu are empty or closed.

Heading north, we stop in Saatse for something to eat. The town seems abandoned and Ilse, a shopkeeper in her late fifties, doesn’t think she’ll be able to stay in business much longer. “Thirty years I’ve been here,” she says. “My clients were Russian. They’d cross the border to buy sausages, beer, sweets. Now I feel the war coming, like a rumble in the distance. Just yesterday I saw Russian helicopters flying there, over those fields. The windows were shaking. At night you hear such a racket you can’t sleep.”

Ilse also lives off of border tourism—visitors drawn by the chill of proximity, the thrill of the invisible line. They come to see the Saatse, a narrow strip of Russian land—close to three hundred acres—that juts into Estonia like the jagged edge of the old empire, cutting off the road connecting two Estonian villages. We crossed it warily on the way in, knowing that if we stopped or even slowed down, we risked arrest.

The Boot’s formation began with a farmer—Ants Uibomäe—who refused to leave his land when the Soviets redrew the borders in 1945. Stalin, implausibly, let him stay. But when Estonia regained its independence in 1991, the Kremlin would not cede the sliver. A grudging compromise ensued: vehicles, even bicycles, would be allowed to pass—but only if they did not stop.

“A lot of people ended up in jail,” Ilse says. “It feels like no one’s there, but then the Russian guards come out of the forest with their guns fixed on you and take you away.”

She tells us of mushroom pickers who were arrested. The former mayor of Värska was taken while jogging. “I think the Russians would like nothing more than to drop a tree across the road and take a busload of Etonians. The perfect excuse to set off mayhem.”

I tell Ilse that after crossing the Saatse Boot, and just before reaching the town itself, we hit another line of barbed wire and weathered border markers crowned with the double-headed eagle—the main element of Russia’s coat of arms, an imperial symbol. It wasn’t clear if we’d left Russia or not—so we erred on the side of caution and held off on stopping to relieve ourselves.

Ilse chuckles as she prepares our herring sandwiches. “That’s just a chunk—size of a tennis court. But yes, technically, another piece of Russia.”

Before the war in Ukraine, there had been plans to trade this geographic absurdity—the Boot—for that protrusion further south, where the deer gather. Instead, Tallinn has decided to fortify the Boot with barbed wire and replace the crossing with an approximately three-mile detour funded by the EU.

This decision seemed all the more urgent after three Russian fighter jets crossed into Estonian airspace for twelve minutes on September 19. On October 10, nearly a dozen Russian soldiers, some disguised in balaclavas, made themselves conspicuous in the middle of the road just on the other side of the Boot’s barbed wire. This immediately brought to mind the so-called “little green men”—special forces without insignia—who had been at the forefront of the Russian occupation of Crimea in 2014.

I meet the man in the gray suit in an upstairs room at the Kohvik Mantelahi, an off-beat pub in Võru, a military hub that until recently was just a sleepy little town about a forty-minute drive from the border.

He has just arrived from Tallin. The tip of his tie pokes out from under his bespoke jacket. He’s younger than I expected, not even fifty, yet he is a key figure in Estonia’s intelligence-and-national-defense apparatus.

His name counts for much less than his words. Arms crossed in front of him, he speaks with a relaxed rhythm—like someone expecting a weekend of sauna and yard work. He tells me that the CIA and Estonian intelligence services believe that once the guns go silent in Ukraine, Moscow will reinforce its western flank with Estonia, like in 2023 in Karelia, when it deployed eighty thousand troops after Finland joined NATO. “A peace treaty in Ukraine means high alert for us,” he explains. “As soon as we mobilize, they’ll call it a provocation.”

He begins to list Estonia’s recent acquisitions: EuroSpike anti-tank missiles, Blue Spear anti-ship system with a 180-mile range, 155 mm self-propelled howitzers from South Korea, Lockheed Martin radars from the US. I ask about boots on the ground. Estonia’s standing army numbers four thousand conscripts, with more than forty thousand in reserve, including the Defense League. On paper, that’s suicide without NATO.

“I’d wait before writing Estonia’s epitaph,” he says nevertheless. “For now, we’re dealing with a rising number of hybrid and intelligence attacks designed to sow panic. Since 2024, the Kremlin has set up a team dedicated to targeting us on social media.”

He remembers 2007, when Russia-based hackers initiated a series of distributed denial of service attacks on Estonia’s public and private organizations—the first cyberattack on a sovereign nation in history. I was in Tallinn that spring, too, when the servers were still smoking. An army of Russian hackers had paralyzed the country, crashing strategic services, websites, and portals in the world’s most digitized democracy. “It’s as if they’ve shut down all our ports at once,” the defense minister told me at the time. The target had been the sovereignty of a country where citizens can use the internet to verify every euro spent by the government.

The clash began with a statue. When the Estonian government decided to relocate a Soviet war memorial from a prominent square in central Tallinn to a cemetery for Red Army soldiers, it framed the move as a way to chase away the shadow of half a century of occupation and thirty thousand Estonians deported to Siberia. But for Moscow, the affront was unforgivable, and the wound still festers.

Russian speakers clashed with police and nationalist groups in the streets. At least six hundred people were arrested, and one hundred and fifty were wounded, police officers among them. One man from the Russophone community was killed. Then came the cyberattack—like a Pearl Harbor, according to the former defense official. After that, NATO set up a cyber defense base in Tallinn. “Unfortunately, we didn’t manage to amend Article 5 to put online attacks on the same level as military ones.”

The man in the gray suit tells me Estonia is preparing to build a “24/7 Maginot Line of drones,” referring to the fortifications the French built in the 1930s to keep out the Nazis. Except this one would be an electronic border wall. “Aside from Ukraine, no one has more experience with drone warfare than Russia,” he says. “We asked Brussels for funding in 2014, right after Crimea, and they laughed at us. They said it was absurd to use drones for defense.”

But Estonia has learned a lesson from Ukraine. “We have a new doctrine now—strike first, inside Russia, with intelligence and military raids,” my source says. “Like Israel. If war seems inevitable, then the safest place to fight is outside your borders. By the time the first Russian crosses into Estonia, it’s already too late. We have to be ready to hit Saint Petersburg, the National Guard, the FSB. It’s what we did in 1919 when we won our independence—we brought the fight to them and kept our population and infrastructure safe. We need preemptive strikes, which require intelligence gathering in enemy territory and maybe mining the front lines with a catapult system. We have to be prepared to escalate the conflict at the first sign of movement from Russia. A small country like ours has to rely on the element of surprise—constant and asymmetric. We have to take the initiative. No tanks? We strike without tanks.”

I point out that what he’s describing sounds catastrophic—like a tiny, heroic Estonia preparing to face the Bear with nothing but catapults, albeit hi-tech ones. “For thirty years, it’s been the only realistic scenario,” he replies.

And what about the nearly two thousand American troops stationed across the Baltic states? Or the nearly one thousand British soldiers deployed in Estonia?

“Did you see what happened in London? Keir Starmer held a summit on the Russian threat—didn’t even invite the Baltic states. And yet Estonia has given more to Ukraine, proportionally, than any other country in Europe.”

He isn’t done yet. “Then there’s Trump. He’s pulling the US away from Europe, flirting openly with Russia. That’s a serious problem for us.”

But none of this is new. “In 1939, the French and British told the Finns to hold on, that they’d send fifty thousand troops to help. They never did. But the Finnish guerrillas wrote a new chapter in history—the Winter War. Hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops were killed. …So when I hear people comparing Starmer to Churchill, I get the chills. Churchill handed us to Stalin at Yalta.”

The Winter War simulation takes place just twenty miles east of Võru. We push deeper into the woods, past Camp Reedo—the first base built in Estonia since 1991, in just a little over a year. From a distance, we spot rows of hangars, sand-colored tanks, and armored vehicles that look more suited for a desert war than a temperate forest. NATO, EU, and Estonian flags fly high above the compound.

A few miles later, we hear the first crack of semiautomatic rifles through the trees. In an instant, we’re in the thick of a simulated battle, surrounded by soldiers fanning out into the woods, ducking behind tree trunks like in a war film. Others move laboriously under the weight of Javelin launchers. Near a half-frozen swamp, a platoon holds its position against a concentric assault, under heavy fire from two armored vehicles, both commanded by women.

“We’re adopting Finnish tactics,” says Colonel Jaan Jessel, head of the exercise. “Our recruits are mentally trained to face enemies ten or twenty times larger and better equipped.”

After two hours of combat, the platoon—despite suffering simulated casualties—breaks the siege and inflicts heavy losses on their attackers. Mock dead and wounded lay in ditches among the bushes, while medics rush in with fake transfusions.

From the sidelines, I spot a few civilians moving awkwardly among the birch trees, their boots sinking into the thawing earth. At first, they look like they are foraging for mushrooms. But as they bend down, I see them collecting spent brass shell casings.

“They’re worth five euros a kilo,” Virgu, a social worker from a nearby village, tells me. “It helps pay the bills. I usually collect around ten kilos after each exercise.” She is the mother of eighteen-year-old twins, both preparing to join the military.

“I’m scared. Russia will eat us for breakfast. We don’t have lithium or oil or anything like that,” she says, leaning in so I can hear her over the crack of gunfire. “But geography—that’s a resource too. We’ll be a great military base again, just like in the Soviet era. It’s not just about knowing how to fight. I have a friend who’s a lieutenant in the infantry. I asked her if she was ready, and she said she already has a plan to escape to Sweden with her son when the time comes. And you know what? At least half the Russians living in Estonia are waiting for Putin like he’s the Messiah. You can see it in their eyes.”

The blue eyes of the young soldiers appear to float on their weary faces, which are streaked in black and green paint. Now and then, someone cracks a joke, and a ripple of laughter briefly breaks the tension. But when I start asking questions, they have no answers. As if the war is too vast a concept to fit inside their twenty-year-old lives. Or too heavy, handed down through generations, too complicated to put into words.

They swallow hard. They speak haltingly about the country they are here to defend, about their sense of duty. About giving it everything they’ve got.

Even their lives?

They all nod. Kris tells me it was simpler for his father, who served in the Soviet Army. “Now he’s afraid for me,” he says.

Märten, from a border village, says “It’s complicated there. You grow up hearing such stories…” I ask him about his hopes for the future. “I want to be rich,” he says. “Buy a Porsche—even a used one.”

Cosmelli and I are standing under a radar tower in Mehikoorma, a village on Lake Peipus, when Kalle Mälberg, a man in his late seventies, pulls up in an old diesel-guzzling Mercedes. He rolls down his window and starts asking a lot of questions, almost like a spy—which, as it turns out, he was.

“I wouldn’t stick around, if I were you. You’re obviously not from around here,” he says, gesturing at the cigarettes we’re rolling. “The last time I saw someone rolling a cigarette was in Australia. Anyway, it’s a French Thomson [Thomson-CSF]”—he points at the radio tower—“and it picks up every piece of crap that gets said on the radio on the other side of the lake. If a taxi driver in Novgorod calls for a prostitute, NATO command hears about it.”

We’ve just walked for hours under an angry sky, tracing the border that runs through the middle of the frozen lake, a plain resembling a cast-iron Sahara bathed in milk-white light. As we traveled, on the Estonian side, fishermen sat hunched over the ice, pulling chub and roach from holes with rods that looked more like wands. In their heavy coats and lowered hoods, they resembled monks in silent devotion, casting fish onto the ice as it flopped and stilled. None of them seemed interested in talking, except for Ivo, a young man with tired blue eyes—the only part of his face we could see through his balaclava. He warned us not to pass the border markers—spaced maybe one hundred feet apart—jutting from the ice. “The Estonians will come stop you, to prevent accidents,” he said. “The Russians will come to cause them.” Ivo’s mother dried the fish he provided to help her make ends meet. He said his friends were mostly resigned about his country’s fate. “They think Estonia is just an illusion,” he said. “They want to leave. But I still believe in it. Besides, there’s mom, the dogs…”

At the center of the lake, an unfathomable silence held sway. Even though Lake Peipus stretches far wider to the north—it measures just over thirty miles at its broadest point—the emptiness felt absolute, the distance from reality ineffable. It was the stillness of a world in hibernation, the surreal atmosphere of a Fellini film.

A lone fisherman pedaled across the ice on a bicycle. Sound slid across the frozen surface with eerie clarity. You could hear a cough from a mile away. Then came a deep rumble—like that of a leaf blower—though we could see nothing on the horizon.

Suddenly, a Russian hovercraft appeared, gliding along with theatrical bravado, flaunting its mounted guns. I asked Ivo what had drawn the Russians—was it us? He shook his head and pointed at a small Estonian drone hovering above us. “They’re challenging each other,” he said. “It’s a language only they understand. Like animals.”

Under the radar tower, Kalle, the former spy, tells us that the effect of that strange, disorienting sound we heard on the lake—seemingly close, but whose source was still quite far away—was used to create an element of surprise in the Battle on the Ice in 1242, when Russian prince Aleksandr Nevsky routed the Teutonic Knights on this southern stretch of Lake Peipus.

Nevsky had staged a retreat, luring the German crusaders onto the frozen lake with the illusion of an easy conquest. Then the Mongol archers had shouted and slammed their shields from multiple directions, their cries amplified by the ice. Disoriented, the Teutonic ranks clustered together. The ice buckled beneath the weight of their armor.

“At least that’s how Sergei Eisenstein tells it,” Kalle says. “The battle itself was irrelevant, but his 1938 film turned it into a kind of trailer for the Great Patriotic War—Nevsky as Stalin, the Teutonic Knights, wearing helmets resembling Wehrmacht Stahlhelms, as the Nazis. But historically, this is where they fell through. And again, in World War II. The Germans won the Battle of Narva in 1944, but here, in Mehikoorma, they folded, and we became Soviet. My father fired at the enemy until the very end. From the old mill on the edge of town.” He explains that the border on Lake Peipus is the oldest in Europe. “For a thousand years, two worlds have been divided by the same water,” he says.

Kalle invites us back to his house, a farmstead of about one hundred acres of forest. He lives off the wood he sells. Behind his cottage, next to the swing set for his grandchildren, is a bunker he built himself. A sign warns off potential intruders: “If you can read this, I’ve already shot you.” The invaders he fears are not the Russians but the “greens.” According to him, one of the advantages of living on the border is the ban on wind turbines. “Plus, if the Russians start launching missiles, they’ll just sail over our heads, no?”

At his home, he serves us an excellent juniper-smoked perch. We eat with our hands, picking at the large tray. Marika, Kalle’s partner, shows us a photo of him as a young man. He looks like a roguish movie star. “My James Bond,” she says.

He began working for the Swedish secret service in the mid-1980s. “I was a nationalist,” Kalle explains. “I had to do my part. Estonia housed seventy-two nuclear warheads—equivalent to the entire arsenal of France—and my job was to map them, first for the Swedes, and then for MI5, which paid better. I was the one who tipped them off about the intercontinental ballistic missile silos buried in Valga and Viljandi, down south. I also spent years studying Soviet defense systems in the Baltic.”

This led to a stint in Australia, where he spent years recruiting KGB agents. “In 1990, a reporter from Pravda, who had stopped getting his pay from Moscow, begged me to help him defect to Australian intelligence. But by then, they didn’t need him anymore.”

Kalle does not lead a dull life here on the border. He paints, sculpts, smokes, and, above all, since the war in Ukraine began, he spends his time snooping on his neighbors.

“There’s a big base in Dubrovo, in the Pskov region, with special forces and paratroopers. They were supposed to capture Kyiv’s airport. Thousands died within the first ten days. They buried them in secret, in a mass grave on the swampy, desert island of Kolpina, on the Russian side of the lake.” Kalle points to the east, as if that place lies just beyond his forest. “I know exactly where,” he assures us.

Driving toward Varnja, along the lake’s most poetic riviera, only Russian radio stations get through—both those from Estonian Russians and from Russia proper. The Estonian government may have blocked access to Putin’s state media, but it can’t block airwaves, just as it can’t control the direction of people’s backyard satellite dishes, which seem to merge seamlessly with the fishing nets and onion braids hanging from the procession of spartan wooden houses that line the shore.

Before leaving Kalles’s cottage, I asked him about the Old Believers of Varnja, a sect that broke off from the Russian Orthodox church centuries ago. “They listen to the soul of Mother Russia—certainly not the BBC,” he says.

Three hundred years ago, they settled halfway up the lake, fleeing persecution in Russia for rejecting what they saw as Western reforms to the Orthodox Church—seemingly minor matters, like the proper way to spell and pronounce Jesus’s name or the manner of making the sign of the cross. Yet those small differences threatened the integrity of the empire. Old Believers became enemies of the czar and the church, which massacred them or sent them to Siberia. Later, Old Believer merchant families funded the Bolsheviks, hoping they would overthrow the system that had oppressed them.

By the 1900s, they had scattered across the world—some ended up in Bolivia, others in New Zealand. Finally, in 2017, Putin issued a statement legitimizing them. He allowed them to apply for Russian passports to encourage their return. It was a harsh blow to the official Church, and the heretics were deeply grateful.

In 2023, I visited their strongholds in the lower Volga, where I documented their messianic support for the war in Ukraine. But here in Varnja and the surrounding villages—where it’s rare to even see another human—no one speaks to me. At the cemetery, in the gardens, or as they stack wood, the Old Believers barely look up from their work. I think I’ve found a willing participant in the elderly priest from Kolkja, another lakeside village, when he comes out to greet me in his long flowing beard and wearing a radiant, toothless smile. But he has just one thing to say: The community is vanishing, and now he only gives mass to a dozen faithful. They don’t even have candles.

I ask about a strange tattoo on his right hand. It looks like a military insignia.

“Prague, 1968!” he exclaims, his eyes flashing. “Tank, boom-boom!” The priest, it turns out, is a former Soviet tank operator.

I saw the Estonian dream take shape in the summer of 1991. The Berlin Wall had collapsed and the Soviet Union along with it. There was no internet—I still have a few wire-service flashes, torn from teleprinters. We were young reporters, drifting through eastern Europe, watching history unfold in real time. We discovered capitals, peoples, faces, smells, songs. New nations were emerging, some tiny, almost exotic. In truth, they weren’t new at all. They were simply being released from a life sentence, ready to sing and dance.

In Helsinki, the Estonian consulate had opened just minutes before my arrival. I got visa number six stamped in my passport. Number five was Tõnu Kaumann, a referee for riding competitions. We crossed the Gulf of Finland together—on a ferry where people were singing and dancing—and he asked me if I had a place to stay in Estonia.

Then Tallinn appeared suddenly in the night, completely in the dark, black on black. Smoke was rising from the chimneys, blurring the moonlight. People wandered the streets, high on freedom.

I stayed with the Kaumanns for two months—Tõnu, his partner Anne, and their teenage son, Tõnis. They lived in a two-bedroom apartment in a khrushchevka, a Soviet housing block on Paldiski Prospekt, stacked with records and books. The air smelled of damp cement, and the elevator always felt like it was on the verge of plummeting. I slept beneath the grand piano. The bathtub was used to pickle cabbage.

The Estonian dream was born in a tavern in the basement of the Tallinn Art Hall on Freedom Square. The KuKu Klubi had been a bohemian haunt since the 1930s, first as a refuge for dissent, then as the brains behind the Singing Revolution. Writers, artists, academics, future prime ministers, and ambassadors would spend hours there, plundering Armenian cognac from the cellars of the ousted KGB.

During that time, a set designer for the national theater took me to the off-limits island of Saaremaa, where they hunted deer on horseback, with bow and arrow. Under Soviet occupation, it functioned as a military base. The set designer’s father, a high-ranking Estonian Communist, still had access to the state retreat for one last summer.

One evening, in the sauna, he whipped me with a birch whisk, or viht, a part of the experience that is said to have health benefits. When I told Anne about it later, back in the apartment on Paldiski Prospekt, her reaction was intense. She cried for days. That man had deported a dozen of her relatives to Siberia. Some had never returned.

The blue eyes of the young soldiers appear to float on their weary faces, which are streaked in black and green paint. Now and then, someone cracks a joke, and a ripple of laughter briefly breaks the tension. But when I start asking questions, they have no answers.

Now, some thirty years after the Singing Revolution, Tõnis Kaumann is an established composer. As Cosmelli and I drive along the final stretch of the border, before it dives into the Baltic, we listen to some of his choral and orchestral work. It’s the perfect soundtrack to accompany us into the outskirts of Narva on this rainy and frigid day. It helps chase away the desolation, the same that clings to the edges of many Russian cities: a sense of impending doom, an eternal bleakness that permeates streets, buildings, bus stops, gas stations, puddles. Estonia, in the image of the USSR. Unlike in the rest of the country, there are no Ukrainian flags flying here.

I was last in Narva in 2014, after the Russian invasion of Crimea. Even then, this city of fifty-six thousand—where 96 percent of the population speaks Russian as a first language—was the place to take the temperature of the border, and to ask whether Estonia was up next.

The setting is epic, made for the lens: Two medieval fortresses stand on either side of the Narva River—which is just five hundred feet wide here—facing off. To the west, Hermann Castle; to the east, the Ivangorod Fortress. Across the river in Ivangorod, beyond the Friendship Bridge, border posts and the steam from a green textile factory hint at a grim existence.

On this side, I am struck by the long line of Russians waiting to be searched and questioned, one by one, before crossing the bridge. Since 2022, cars have been banned. Only about a thousand to fifteen hundred people a day, on average, are allowed through, many of whom cross with special permits to visit family. There are no benches or roofs. “I’ve been here for six hours,” says a middle-aged woman who is so bundled up it’s almost comical. “I bring groceries and medicine to my mother once a week. Why does it have to be so hard?”

The head of the border police, Egert Belitšev, told me over the phone that humanity and security are incompatible here. “Putin is obsessed with Narva,” he explained. “After invading Ukraine, he mentioned Narva specifically—called it a historic part of Russia. He doesn’t think our independence will last. That makes anyone a potential threat to us.” Indeed, border police face constant acts of sabotage. “Since the beginning of 2024 alone, the Russians have removed or shifted the river buoys ninety-six times,” Belitšev said. “They jam our communications and GPS signals. We can’t let our guard down. Especially not on that fucking bridge. If you’re going to Russia, don’t expect us to roll out the red carpet.”

Lieutenant Tarno Hutt lets me take a peek at an outbound checkpoint. Detection dogs—trained to sniff out currency and electronics—pace nervously among emptied suitcases.

“We’re making sure the sanctions aren’t being bypassed,” says Hutt. He won’t say much about the questioning—which is most intense for those entering Estonia—but the people in line say it rivals the zeal of the FSB.

Hutt and I cautiously make our way across the bridge. He has orders to avoid triggering the Russian guards standing a few dozen feet behind the “dragon’s teeth,” conical anti-tank barriers. He tells me the Russians routinely blast patriotic anthems from the walls of their fortress. Or they paint Zs on the hot-air balloons floating over their side of the river. “They want a reaction. Something they can use.”

One such reaction is that starting in 2023, every May 9—the anniversary of the Red Army’s triumph in World War II—the Narva Museum hangs a blow-up photo of Putin’s bloodied face on its eastern wall, along with the writing war criminal. But according to Hutt, this is still a mild gesture.

For now, it’s just a war of nerves, led in part by Mayor Katri Raik, the former interior minister, whom locals call the panzer mayor. When I meet her at city hall, she cuts me off before I can finish my first question.

“Narva hasn’t been this close to war since 1944,” she says.

That year was like a reverse Stalingrad: German forces dug in against the Soviet advance in the Battle of Narva and tens of thousands of troops were killed—many of them Estonians fighting on both sides. In the end, the Red Army broke through farther south, near Lake Peipus, just as Kalle told us. Narva was leveled, then Stalin built Soviet-style buildings, erasing the local architecture.

I ask the mayor about the impact of the government’s new policies, including the ban on Russian-language schools, the dismantling of Soviet-era monuments, the fact that two-thirds of the city’s Russian speakers remain stateless, unable to vote or hold government jobs.

“The real mistake,” she says, “was not doing it in 1991.” She is more concerned about growing poverty, shuttered storefronts, the cost of heating. “Unemployment here is 15 percent—more than double the national average. That doesn’t exactly foster social peace.”

She returns to the events of 1944. “We won’t allow history to repeat itself. When it comes to defending our independence, we’ll fight to the death.”

Narva is Estonia’s national taboo—the epicenter of the Russian question. It encapsulates all the reasons why the patriotic, romantic spirit of the early ’90s soured into bitter nationalism.

“The rest of Estonia sees Narva as its very own Siberia. We’re their secret shame,” says Aleksei Ivanov as we walk along the river. He is a cultural liaison for the Russian community, though his beard is more hipster than Orthodox. “If you want clicks, just add ‘Narva,’ ‘Russia,’ or ‘border’ to your post,” he adds.

Nearby, a fisherman is wading into the river, casting into Russian waters. On the opposite bank, the same scene appears in reverse.

Ivanov is one of the few Russian speakers who have managed to gain Estonian citizenship, having passed the notoriously difficult exam in language and culture. “Because I had a thing with the teacher, who let me cheat,” he says. Still, when he tried to join a government delegation to San Francisco, the US embassy in Tallinn denied him a visa.

“A lot of young Russians here are trying to change their last names to sound more Estonian. Like if I were to call myself Juhan instead of Ivanov,” he says. “It’s terrifying. The truth is, out here on the border, we’re landless, untouchable—the human rejects of two worlds. Too Russian for Estonia, too Estonian for Russia.”

“I wish I were a crow,” he says, pointing at a flock cawing above us in the invasion-gray light of the late afternoon. We watch them fly across the river, from one fortress to the other, heedless of the border.

Elettra Pauletto is a writer and a translator of French and Italian literature. She divides her time between Italy and western Massachusetts. Her next translated book, Volga Blues: A Journey into the Heart of Russia, by Marzio Mian, is forthcoming (Norton, 2026).

Alessandro Cosmelli is an award-winning photographer who has published five monographs, including Oltrenero (Contrasto, 2009) and Brooklyn Buzz (Damiani, 2012), which were both recognized by Pictures of the Year International as being among the best photography books of the year.