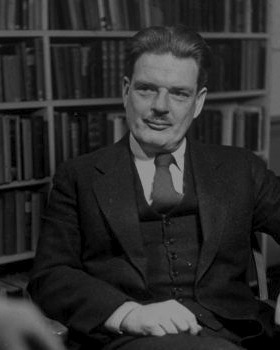

- Sherwood Anderson, circa 1930.

On November 14, 1930—seventy-five years after the Battle of Appomattox and one full year into the Great Depression—Sherwood Anderson stood in front of a crowd 3,500 hundred people in the ex-Confederacy’s capitol to introduce a public debate over the economic future of the South. The Richmond Times-Dispatch was sponsoring the event—a debate, “Agrarianism versus Industrialism,” between VQR editor Stringfellow Barr and poet and critic John Crowe Ransom. Even before Anderson assumed the lectern, the evening had become an intellectual moment that had, in the words of Times-Dispatch editors, “assumed the proportions of national importance.”

At 8:30 P.M., the walls of the City Auditorium lined with latecomers and a “squad of Boy Scouts” who served as ushers, Anderson read a speech he had prepared for the event. Far from a simple introduction, Anderson’s address framed the debate, highlighted the speakers’ main points, and then offered the audience his take on the South’s “new industrial experiment.”

The Times-Dispatch, reporting on the debate the following day, focused mainly on Anderson’s critique of Sinclair Lewis, the recent winner of the Nobel Prize in literature, but the rest of Anderson’s introductory essay tackling the question of Industrialism vs. Agrarianism went largely uncovered. This speech is the work of a literary giant from the industrial North, living in the agrarian South, and introducing the “Agrarian” John Crowe Ransom who “isn’t a farmer” and the “Industrialist” Stringfellow Barr who “doesn’t manufacture anything.” Anderson presented the audience with a middle position. He was both fascinated and terrified by machines.

His words won thunderous approval from the audience, but they have never been published in full—until now.

* * *

A former critic of small-town American life in his native Ohio, Anderson was by then a Virginia country gentleman—though the move represented no idealogical shift. After spending a summer vacationing in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Anderson had simply decided that he “felt at home there.” With its welcoming people and rolling countryside, the Virginia hill country seemed to beckon him—“something had drawn me south[,] something I had felt since boyhood.” Using the royalties from his best-selling novel Dark Laughter, he bought a small farm in Troutdale, Virginia, in 1925, and built rustic log-and-stone country manor he named Ripshin, after a nearby stream—but within a year Anderson grew restless. Learning that two weekly newspapers in Marion (about twenty-two miles from Ripshin) were for sale, he snapped them up—one, the Marion Democrat, a Democratic paper, the other, Smyth County News, a Republican—and became editor and publisher to both. Despite no previous newspaper experience, Anderson immersed himself in his journalistic experiment.

He began keenly observing, recording, and reporting the small-town goings-on of neighborhood council meetings, court trials, boxing matches, and country fairs. He especially looked forward to speaking with the townspeople of Marion. He loved to “wander about … to sit with people, listen to words.” Anderson dug up news on everything from casual town gossip to local exposés on the poor jail conditions or the need for a new Negro school in Marion. Anderson firmly believed there was no better influence than “country papers to get after better country government.”

By the late 1920s, the South’s sweeping industrial movement had piqued his interest. Anderson began visiting various sites of labor unrest across the South, speaking candidly with workers and factory owners about their roles and experiences in the Southern industrial movement. While on the road in January 1930, Anderson wrote to a friend in between factory visits: “I’ve just a hunch, a feeling, that the story of labor and the growing industrialism is the great, big story of America.” While inspired by the rhythmic precision and technical efficiency of industrial machinery, harboring a deep sense of awe for the factories’ lively uniformity, Anderson was consciously aware of the dangerous tendency of industrialization to “throw men out of work, make a few men rich, pretty much destroy craftsmanship.” He often acknowledged industrialization as an inevitable effect of modernization, but he also argued that the “dignity modern men have built into their machines” should reflect the important place of the worker in the community, especially as they faced the accelerating encroachment of industrial standardization

While Anderson, the farmer-newspaper man from industrial Ohio, was wandering the New South in support of the worker, a group of twelve Nashville Agrarians were plotting a philosophical return to the Old South. Most of the twelve were in some way affiliated with Vanderbilt University and four of them—John Crowe Ransom, Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, and Donald Davidson—were originally members of the Fugitive poetry group that sparked the literary Southern Renaissance. These Fugitive-Agrarians spent the early 1920s disillusioned with and rebelling against the stale, overly-romanticized literature of the South. But by 1925, the southern landscape had changed dramatically: factories were replacing farms, science was challenging religion, and Americans were choosing the promise of mobility and convenience over roots and stability. For the Agrarians, the American celebration of materialism, consumption, and blind progress was at odds with the tradition of the South. This constant “pioneering on principle” was stifling the “full life of the mind” and sinking the spiritual and artistic life of the individual. The Agrarians declared war against Industrialism to save the soul of modern man.

- John Crowe Ransom

As early as 1926, John Crowe Ransom and Allen Tate decided they “must do something about Southern history and the culture of the South.” They began discussing a possible “symposium on Southern letters,” and by 1930, a book of Agrarian essays called I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition was in the works. Ransom began drafting the “Statement of Principles” (originally “Articles of Agrarian Reform”) and there was serious talk of acquiring a county newspaper. I’ll Take My Stand promoted a return to a culture of the soil, a leisurely and dignified life of labor, and argued for a renewed and genuine humanism, “a Southern way of life against what may be called the American or prevailing way.”

- Stringfellow Barr in his office.

Stringfellow Barr, a history professor at the University of Virginia and managing editor of the Virginia Quarterly Review, was initially recruited by the Agrarians to contribute an essay. He wrote back that while he couldn’t sign their manifesto he was still interested in possibly “coming in through the back door.” He sent them an outline of his essay “Shall Slavery Come South?”—a call for regulated industrialism and a sideways crack at the reactionary thinking of the Southern “traditionalists.” The outraged Agrarians rejected Barr’s essay and barred him from the book. They were beginning to realize that their first battle would not be against an army of invading industrial Northerners, but a league of liberal Southerners.

Undeterred, Barr expanded and published his essay in the October 1930 issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review—the same issue he took over as editor of the magazine. In 1930, VQR was a five-year-old quarterly that considered itself “an organ of liberal opinion” and “national discussion” with at least “one article provocative of intelligent interest in Southern problems on the title page of each issue.” In the contributors notes, founding editor James Southall Wilson wrote, “‘Shall Slavery Come South?’ presents the views of a young Southerner who is sympathetic with the older traditions of the South but who believes that the proper attitude toward the industrial situation is sympathetic cooperation and control.” In the early 1920s, after finishing his Rhodes Scholarship, Barr had spent time in Namur, Belgium, studying the calculated and horrifying effects of industrialization. He saw that tired child laborers working ten-hour days would often fall into the machines. Not only were their lives ruined or lost, but the cleaning of the machines would cost factory bosses more than they saved by hiring the children at low wages. But Barr believed that industrialism was the key to the future of the New South and that “the ex-Confederacy has embarked on the Industrial Revolution.” The key for the South was regulating the “new industrial experiment” so that it could “rehabilitate her economically without wrecking her spiritually.”

The essay outraged the Agrarians—and Ransom, Tate, and Davidson sent an open letter to VQR and a Tennessee newspaper claiming Barr had “abandoned the Southern tradition. Its virtues were leisure, kindliness, and the enjoyment of a simple life.” The letter was picked up by the Associated Press and circulated across the country. Barr responded with an open letter of his own and the two sides waged war over the AP wires for several weeks before George Fort Milton—publisher of the Chattanooga News—visited Charlottesville, stopped by the VQR offices, and “suggested in a jocular way that a debate ought to be arranged.” Lambert Davis, VQR’s new managing editor, latched on to the idea. He proposed a debate between Barr and one of the Agrarians in either Nashville, Charlottesville, or a neutral site like Richmond in a letter to Donald Davidson. Davidson agreed and a few days later Davis convinced Allen Cleaton, managing editor of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, to have the newspaper sponsor the debate in Richmond. While discussing the particulars of the event and how to publicize it, Cleaton wrote Davidson that the event was scheduled for 8 P.M., November 14, 1930—two days after I’ll Take My Stand would be released—and that the topic of the debate would be “Regulated Industrialism vs. Agrarianism.” Davidson wrote back saying John Crowe Ransom would be the group’s speaker and that, “We dislike use of the word regulated in question for debate. Prefer sharp statement Industrialism vs. Agrarianism or simply Shall the South Go Industrial.”

* * *

That same October, Sherwood Anderson was working on an article for VQR about J.J. Lankes and his woodcuts. Lankes’ work, to Anderson’s eye, revealed “something significant and lovely in commonplace things,” even during the “spiritually tired time” of the early 1930s. During their correspondence Anderson wrote Barr to compliment him on his controversial article “Shall Slavery Come South?” A week later, while planning and publicizing the upcoming debate, Lambert Davis wrote Anderson to see if he would be interested in moderating the event. Anderson, who had recently turned over the daily operations of his two newspapers to his son, enthusiastically accepted, and on October 30 Davis wrote the Agrarians, “I think, all things considered, the selection of Anderson a very wise one … Anderson has the advantage of being a good person from a publicity point of view and also a man who has first-hand experience of both the industrial and agrarian regimes.” As both a Midwesterner attuned to industrial developments and an “adopted” Southerner participating in rural life in southwest Virginia, Anderson seemed a knowledgeable, nonpartisan choice. While preparing for the event, Anderson read an advance copy of I’ll Take My Stand, calling it, “At least … an expression of something.” He then sent a letter to Stringfellow Barr, enigmatically alluding to “an idea” that he wanted to “spring on” Barr and Ransom during the debate.

On November 14, 1930, the Richmond Times-Dispatch ran the headline: “Speakers to Be Introduced by Distinguished Author and Editor” and promised “Notable Visitors Plan to Hear Arguments Vital to Section’s Future.” Some of the “notable visitors” included the governor of Virginia, the mayor of Richmond, and presidents and faculty members from nearby universities. The debate could not be heard on the radio, but “the entire main floor and balcony of the City Auditorium [would] be thrown open without charge.”

By 8 P.M. that evening, the Richmond City Auditorium was completely full. Thirty minutes later, Anderson rose to introduce the speakers: “It is with a real pleasure that I come here to Richmond to hear this debate, and that is what I came here for … to hear other men talk, not to talk myself. However, here I am.” The self-proclaimed “illegitimate son” of Virginia then read his lengthy and unexpected speech introducing the contenders and highlighting the central question of the debate: whether the South should “attempt to recreate the old Southern life” or “embrace industrialism and try to make of it something better.”

Anderson’s introduction, like his short stories and newspaper articles, demonstrated his keen understanding of the issues surrounding industrialization. Using short, declarative, and often conversational sentences, Anderson simplified the conundrum and reached for the heart of the problem:

We are, as everyone knows, in a time of depression. Well, the depression is not altogether a financial matter. It is deeper than that. This is, I think, not only in the South but throughout all America a time when thoughtful or sensitive people are beginning to question … our American life.

He emphasized the importance of a critical, questioning American spirit and the importance of individualism, especially in a post-boom Depression era reeling from the corruptions of “bigness” and the dehumanizing effects of mechanization. Anderson described how men and women were “beginning to blame this industrial monster … beginning to ask questions” about “the grand manner” of progress. He believed there was “a tendency … for modern industrialized man to lose sense of earth, sun, stars, fellow men and even his own hands,” and that life in the North was “too much the life of the closed fist. There does still remain in the South something that suggests the life of the open hand.”

Anderson seemed to outline a pro-Agrarian stance at odds with the effects of Industrialization, yet he made it clear that he saw the most danger rooted in how the South would respond to and eventually implement Industrialism. Overall, he thought Barr and Ransom were “really up to about the same thing. They have different slants but the same impulse.”

Anderson then turned the meeting over to the two debaters and sat down to a thundering applause. John Crowe Ransom took the stage first and read his carefully written and well-prepared argument for nearly an hour. His presentation was serious and a bit stiff, but persuasive and sincere. He argued that “Mr. Barr nor anybody else will ever succeed in regulating into industrialism the dignity of personality, which is gone as soon as the man from the farm goes in at the factory door,” and closed with an Agrarian “prescription to live by” of “fresh air and sunshine, and contact with the elemental soil, and leisure instead of hurry.”

Barr then delivered a short, but fiery and animated twenty-minute address using only notes and speaking in sharp, energetic one-liners. Barr thought it was time to stop “creating out of the farm a mystic lost cause.” To deny the arrival of Industrialism was to live with eyes closed. “I accept the weather,” Barr announced, “and I accept industrialism.” Southerners needed to “study industry and devise methods for its control … not go off in the corner and pout, saying we don’t like factories.” He ended his speech theatrically, saying, “When problems are complex, you ought never to cry ‘I’ll Take My Stand’ but ‘Sit Down and Think,’” then quickly took his seat to “roars of laughter.”

The two debaters then gave brief rebuttals and by 11 P.M. the event was over. No official winner was declared, and Sherwood Anderson left Richmond the next morning feeling as though he had “stolen the show”—had, in fact, “been the show.” One month later, after a follow-up debate in New Orleans with William S. Knickerbocker, editor of the Sewanee Review, Ransom admitted that despite his “solid and systematic argument,” he had been given a “thorough trouncing” in Richmond. Barr seemed to agree, later writing, “quite suddenly I turned ironical and ribald … a more skilled debater than Ransom could have made me pay dearly for the intellectual arson I was committing … . But I think many of my listeners shared my desire not to go to Namur while singing Dixie!”

* * *

Despite the immense success of his speech, Anderson’s text never appeared in print. Indeed, until now, only portions of the lecture have appeared—most notably in Southern Odyssey: Selected Writings by Sherwood Anderson, published by the University of Georgia Press in 1997. It appears here for the first time in its totality courtesy of Charles E. Modlin and Hilbert H. Campbell, Trustees of the Sherwood Anderson Literary Estate Trust, and the Newberry Library in Chicago, where the most complete typescript of Anderson’s remarks is held.

Eighty years removed from the debate, Anderson’s speech—and the entire debate between Barr and Ransom—seems more relevant than ever. Anderson’s sensitive exploring of the inherent tension between progress and tradition reveals how intimately he had explored and engaged in Southern life—publishing regional newspapers, farming the Virginia hill country, visiting factories, and interacting with Southern communities. In Richmond, Anderson said, “I would like to be, for a change, a little worm, let us say, in the apple of progress. I’m fed up on progress.”

The Agrarians continued their campaign against the machine-age in scholarly journals, newspaper articles, public debates, and eventually a second anthology—their last stand. They were never able to purchase a county newspaper and only a handful of them ever actually retreated to the farm, but Barr’s vision of a Regulated Industrialism, too, has gone by the wayside. From the distance of history, we can see that Anderson was right: Barr and Ransom were fundamentally after the same thing—preserving a connection to the land and a meaningful way of life. Barr believed it could be achieved through careful regulation. Ransom feared that the factory would overtake culture. Today, in the era of “too big to fail,” the debate continues—and more and more people find themselves in sympathy with Sherwood Anderson’s characterization of himself as “an American who is fed up with bigness.”

* * *

Text of Sherwood Anderson’s Speech

It is with a real pleasure that I come here to Richmond to hear this debate, and that is what I came here for … to hear other men talk, not to talk myself.

However, here I am. I am expected to formally introduce the speakers: Mr. Stringfellow Barr, of the University of Virginia, editor of The Virginia Quarterly, Southerner, gentleman, writer, and, I believe, a good intellectual scrapper; and Mr. John Crowe Ransom.

John Ransom is of Vanderbilt University, at Nashville, Tennessee. He is professor of English out there but he is a lot more than that. Why, I remember some years ago I was, for a season, myself a real speaker. I went lecturing. A lot of colleges and universities had me. I met a lot of professors of English at that time and I remember what a college boy once said to me. This was at a middlewestern university. A professor of English introduced me. Really I ought to get even now that I am here and have this chance at two university professors but I won’t. I will refrain. I have a large Christian spirit.

I was going on to speak that time, after that college professor of English got through with me, when this boy rushed up to me. “Say,” he said, “For God’s sake, don’t judge us by him.”

“It’s all right,” I said, “ they are all like him.”

Now what I want to say to you is that I was wrong. They aren’t all like that. Stringfellow Barr isn’t like that and John Ransom isn’t. He is a man. Like Barr he is a gentleman. More than that he is one of the really significant American poets. A poet, if he is “like that,” isn’t a poet and John Ransom is a poet.

And right here, while I have this chance, I would like to speak of a book, just published and of which Mr. Ransom, together with eleven other Southern men, is the author. The book is called “I’LL TAKE MY STAND”, and it is an attempt to express what thousands of young men in America are feeling now-a-days. I wish every one in this audience would read that book. I wish every young man and woman in American would read it.

These two men, Mr. Barr and Mr. Ransom, are to have an intellectual scrap out here before you. They are to debate the question: … industrialism vs. agrarianism. They are going to debate that question although John Ransom isn’t a farmer and Stringfellow Barr doesn’t manufacture anything.

That’s good.

There are a lot of things about this meeting and the speeches we are to hear tonight that are good. Here we are in a period of hard times. For years now industrialism has been sweeping over America. It has crept out of New England and other Atlantic coast states of the North, has pretty much covered all the middle western states, and is invading the South.

It was brought to us with, you all know, what promises. The machine, that marvelous and often beautiful product of man’s brain, was to do everything for us. All we had to do was to get aboard. We were to be sent whirling and pitching and flying into a new heaven. We were to live in peace and happiness on earth, loving each other. We were to have plenty and the books, I dare say, still show we have plenty. We are still, I fancy, the richest nation on earth but are you—individuals here tonight—personally rich? Have you got any of this money? Are you happy and contented?

What is wrong.

That is the question people are asking now-a-days. Why, they aren’t really blaming Mr. Hoover. They are beginning to blame this industrial monster to which we, as Americans, have surrendered. They are beginning to ask questions. There is a movement started in America and, thank God, it is a young man’s movement.

We have all been enamored of bigness. It has been the American disease, the American passion. Everything here has been judged by bigness. The book that sold the most copies was the best book; the man who got the richest was the wisest man. In literature, we have been in what I think I might call the Wise-Cracker age. To be serious about anything was absurd. There has been no interest in public life. The best of our young men were taught, almost from the cradle, to think of bigness. To stay put for example, living you life in the country or in a small town, was to be a hick, a fool, a boob.

Why, we have recently seen something that I think you will all agree with me is pretty amazing. We have seen the Noble Prize for literature given to Mr. Lewis, the author of “MAIN STREET,” a man who has always hated the American scene … the man who has perhaps done more than any living American to make life, the life of the average American and in particular the life of the American of the farms and the small towns, seem altogether mean and ugly. They have given this prize to Mr. Lewis after considering, we are told, the work of a man like Mr. Dreiser, a tender man, a man full of human sympathy for the life about him.

We have at any rate an amazingly interesting spectacle, the Nobel prize given to a hater, not to a lover of American life.

There are a lot of things about this meeting and this debate. Personally, I am not much worried about these two men … Barr and Ransom. I think they are really up to about the same thing. They have different slants but the same impulse. That is about it. This debate is being held in Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the Southern confederacy and that is good too. Now I want you here in this audience to take a look at me. I’m not so young. I’m a post-Civil War man, not a Post-World War man. I’m not a son of Virginia. If there is any connection between a man like me and the state of Virginia it will not bear going into too closely. If I am in any sense at all a son of Virginia I am an illegitimate son.

And I am here, a middle-westerner, as I have suggested, whose father fought on the Northern side during the Civil War and I am introducing these two men who are both interested in combating the effects of the Northern victory in that war.

The South fought that war and lost it but do not be confused by that fact. The North fought and lost it too. They got something they never knew they were fighting for or they wouldn’t have fought. They got industrialism. Do not be confused about that. There are a lot of Northern men not so sure now-a-days that the results of the Civil War in America were exactly the glad joyous things we have all, North and South, been told they were.

This debate here concerns, as I understand it, primarily the South, what attitude the South shall take toward this strange perplexing new life into which we are all now-a-days plunged because of the machine.

We are, as everyone knows, in a time of depression. Well, the depression is not altogether a financial matter. It is deeper than that. This is, I think, not only in the South but throughout all America a time when thoughtful or sensitive people are beginning to question, as perhaps it has never been questioned before, the tone and effect on all of us of our American life.

We are to hear debated here the question as to whether it is better for the South to definitely attempt to set its face against industrialism and attempt to recreate the old Southern life, an agrarian life, or whether it shall embrace industrialism and try to make of it something better … more fitted to the needs of Southern people.

The two men who are to speak to you here are both highly intelligent men. They are both poets and scholars. They are both men who are in earnest and, on the whole, I think it rather a happy chance that I have been asked to introduce them.

I am myself, as I have said, not a Southerner. I was born in the industrial North, under the shadow of the very kind of factories that are now invading the South and so profoundly affecting Southern life. At present I live in the South and I shall spend the rest of my days in the South and I can truly say that since I have been a grown man there has always been in me something that has called me South.

And it is not because of the climate or the soil down here. It is not because of your Southern aristocracy. I don’t believe in that in one way but there is a way in which I do believe. I am, I hope, not the kind of man, so commonly found in the North, … a professional Southerner. In so far as you born Southerners become pretentious, in your Southerness, thinking that your own cotton raising fathers were better than my corn and steer raising middle-western fathers, I am against you, but in so far as you hold up the ideal of an aristocracy as meaning a desire for gentleness, for sympathy, for tenderness toward life, I’m for you.

What I like about the South is that I think that you do hold onto something like this.

I have been coming South since I was a young man. I am a writer and almost every book I have ever written has been written in the South. There is yet (who with any knowledge of American life can doubt it) a difference in the tone of life in the North and in the South.

It is because of industrialism, these factories sweeping across the country, invading cities, invading towns. They have changed things.

But I am not going to cut into the field of these speakers here tonight. What I am trying to say to you is that in the North, in my day, life has been too much the life of the closed fist. There does still remain in the South something that suggests the life of the open hand.

Well, I like the life of the open hand. I think it is the only decent life. I think success has been overdone in America. I think bigness has been overdone. Personally, I would like to think of myself as not primarily a Northerner or a Southerner but as an American who is fed up with bigness, with the grand manner. I would like to be, for a change, a little worm, let us say, in the apple of progress. I’m fed up on progress, represented only by money, too.

I like also the idea of the Southern man, Mr. Stringfellow Barr of the University of Virginia and Mr. John Crowe Ransom of Vanderbilt University, coming here to debate a question like this. Why, as to what we shall do with the machine, with industrialism, it is overwhelmingly the biggest question men and women are now facing.

Not so long ago, in my own lifetime at least, and at least in the North, no man would have dared question industrialism. It has a lot to answer for. It has killed or is killing, many of us believe, some of the finest and most basic of man’s impulses.

There is a tendency, who can doubt it, for modern industrialized man to lose sense of earth, sun, stars, fellow men and even his own hands. The machine, so blithely accepted by most of us, is doing all sorts of obscure and hateful things to men. Why, the very automobile in which I drove here to this meeting from my home in Virginia’s Southwest does something to me every time I drive it.

And there is something else. You will find everywhere in American now-a-days thoughtful men who believe that industrialism, unchecked, must lead straight into communism. They do not want communism. They believe that individualism should have yet another chance. Communism and Industrialism are really brothers; in both of them there is implicit the same patronism, the same determined regimentation of life, the same determinism to crush individualism.

For one thing there has been released, into our hands by industrialism, all of this new power. Now power and in particular this sort of vicarious power, unearned, uncreated by man, is dangerous to us. That we accept it so blithely shows a kind of stupidity in us and, in as much as we accept the vicarious power released into the world by the machine as our own power and become proud and vain because of it, we are fools.

Real power is something very different; I mean imaginative power, creative power, power of the hands and of the head. It is a long slow job coming at that kind of power and the effort to get it commonly makes a man more humble, not more arrogant and proud as does the power we are getting now-a-days so cheaply from the machine.

But I think we are all beginning to understand this. We understand that every man and woman now living is in danger. What is endangered is our real manhood and womanhood.

Both of these men who are to speak here tonight, Mr. Stringfellow Barr and Mr. John Crowe Ransom, have as clear a vision of the danger of which I speak as any two men in America could have. They have different ideas as to how to meet the situation. I will therefore turn the meeting over to them and do what I came here to do, that is to say, sit and listen.