The laws of war make for a brittle pact at best, and can seem like a tragic fallacy up against an army’s nihilistic impulses. Russia’s tactics in Ukraine prove as much: atrocities in Bucha; the bombing of a maternity hospital in Kharkiv; imprisoning and terrorizing children in Yahidne; the shelling of civilian evacuees fleeing Irpin. And what’s to be done after the fact? What justice could possibly suffice? Father Andriy Galavin, of the Church of St. Andrew in Bucha, has no illusions about how far the road to healing runs. “Christ wants us to forgive, but not just to say the words. This should be said with sincerity,” he told the London Times in August. “We don’t know how many decades it will take for us to be ready to forgive.”

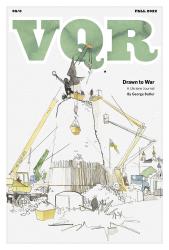

Russia’s crimes will shape how the story of this war is told and retold. It will be molded, too, by Ukraine’s resilience and scattershot victories. Of course, the power in these narratives emanates not just from the plot points but from the voices of soldiers and civilians—of civilians in particular, who are always at the mercy of war’s violence. Voices are key to George Butler’s illustrated reportage, whether in conflict zones or along migration routes, in a Munich courtroom or on an oil rig in the North Sea—wherever humanity is expressed under pressure. Such experiences—especially in wartime—are often found through a second telling of a familiar story, one that captures, through deliberately slower reporting, subtleties that can get squeezed out of the news cycle’s rapid metabolism. “The reason I go to places like this and draw is because I believe that there are many missed opportunities in the storytelling,” Butler told me. “There are many spaces in between—around the fringes of these atrocities—that demand more depth, better stories about vulnerable areas and vulnerable people and trying to tell the truth as they’ve told it to me.”

There is, then, pathos in a drawn line that is distinct from the power of a sentence or a quote from a source. I asked Butler what it is about this medium that allows for such emotional resonance. What is it about drawing inside a crisis that sets it apart from other reporting?

“The process of taking more time and talking, for one thing,” he said. “The piece of paper being available for people to see—it’s less intimidating. It’s slow and it’s open and it’s honest. And it works both ways. For the viewer, the creative language of mark-making, communicating in this particular way, is as old as time. This has been part of how we express the human condition for millennia. And so if you see something that’s handmade or spoken or delivered in this way by another human being, then you spend more time with it. I think the more vulnerable the moment, the more sensitive you have to be, and that’s why drawing works so well.”

Butler has been at this for more than a decade, using ink and watercolor to capture individuals navigating extraordinary and often dangerous circumstances. When I asked him if Ukraine was any more or less risky than other assignments, his forthrightness surprised me.

“They all have their moments of being difficult,” he said. “Ukraine was easy, in a way, because it was easy to get stuff published, because the world was so outraged—particularly in Europe. Ukrainians were white people who were close by and Russia was a big easy enemy to write about. And so we bought into Zelensky’s point of view very easily—and rightly so. In that sense, it was great to have an audience and to know that the work was going to be seen. But from a practical point of view, it’s always sad. The civilian vulnerability is the same in all of these places. They’re the ones who get caught up in it, and they’re the ones who pay the price. That was similar in Syria and Iraq and Afghanistan and other places.”

This suggested an occassional apathy toward his work, which surprised me considering how well regarded he is as an artist.

“I spent a month in Libya, a month in Angola—forty years of civil war, now 1,200 minefields cover it from one side to the other, one of the poorest places on Earth with the most potential. I spent a week with an ex-general in the desert in Yemen, with a militia there. That was meant to get into a newspaper in America that sort of canned it. I spent two weeks in Armenia drawing a country on its knees, beaten up by Turkey and watched over by the rest of the world. But that was sacked off for stories about COVID. So it’s sort of fickle and irritating. And yeah, I contribute to it when I start making news about Ukraine and not about Afghanistan.”

Did he think he was an active participant in that lopsidedness?

“We all are.”

A sobering point. The predictable path for this introduction, then, leads past the atrocities of war, which get plenty of coverage, toward the heroic gestures and bravery of civilians in wartime. This was, in fact, what moved us to assign the project in the first place. But in talking about the war in Ukraine, we’re also talking about the narrative of war itself and how conflicts are remembered, what shapes the paths we use to look back on history. To be reminded that there are multiple narratives of this very same kind that are ignored, whether out of bias or lack of bandwidth, is to be reminded of how history is partitioned by cultures, and how some histories are prioritized at a greater scale than others.

“It’s about truth,” Butler added. “What the truth is in the moment that you’re recording it—the war that you see—is the moment that it sort of disappears into the ether.”