Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

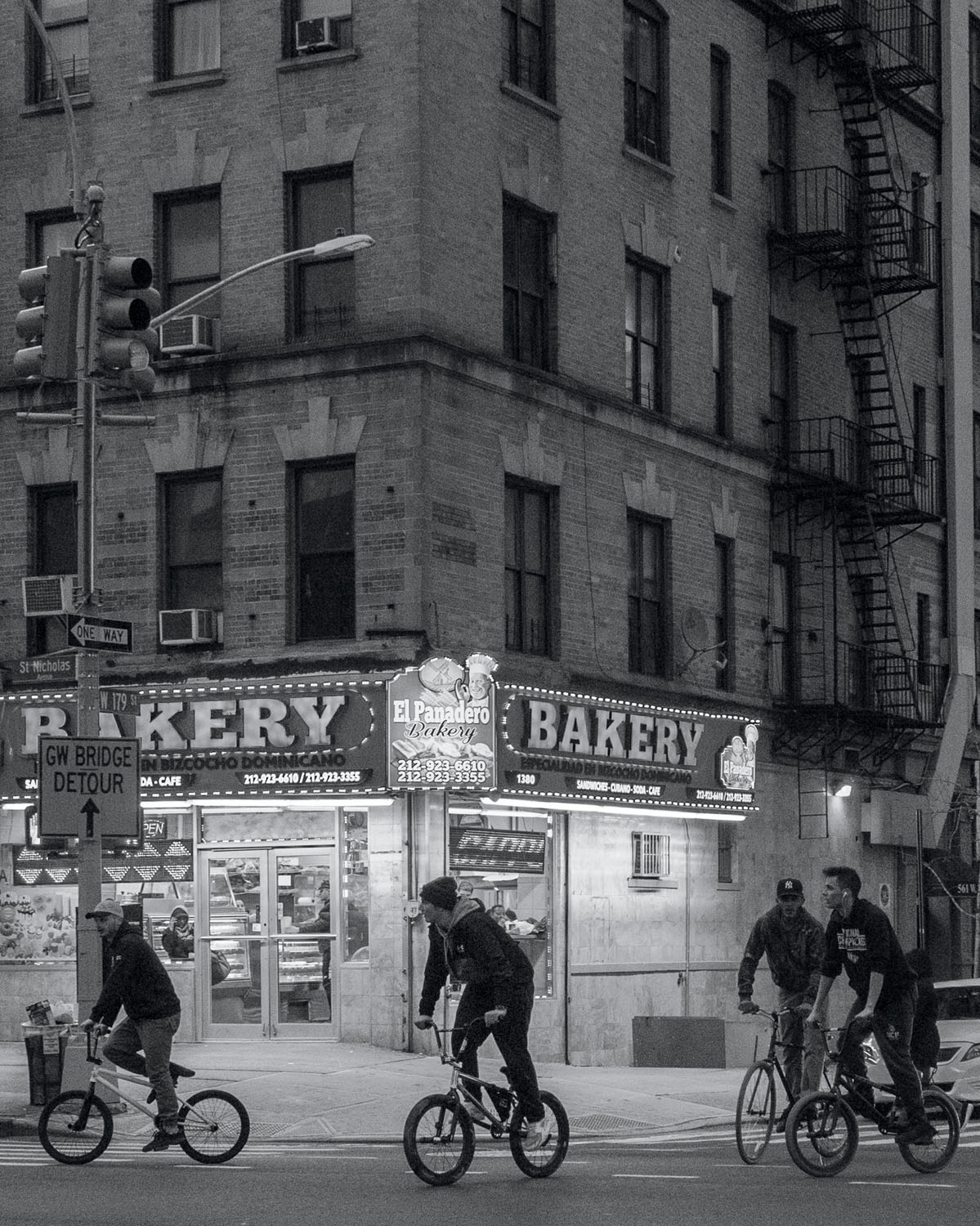

Carlos Rivera is a Puerto Rican–born street photographer currently residing in New York City. His movement, #yerrruptown, has been steadily gaining traction on social media. Documenting everyday life Uptown, Rivera highlights the issue of social displacement that comes with gentrification. Currently his work is being featured in The Codes of...