The Devil’s Crown

I.

The third time I go to meet the devil, I pay better attention to the legend and visit on Halloween. The day is either cliché or the deep human instinct that there are times in the year when it is wise to fear. The air has finally turned cold and the windshield fogs as I drive, wending past unhaunted cemeteries and political yard signs, aiming in the dark for the small-town cemetery in Stull, Kansas, that has grown from a minor curiosity for me to a compulsion. Although I doubt the rumors, a slight lick of fear in my chest tells me I might believe the devil will visit the grave of his son tonight.

Although I’ve never come in the dark before, I know the pastures and the road’s difficult curves, and as the signs for town appear, so do flashing lights. On the bridge into town sits an abandoned car, a tow truck in front of it. College kids looking for the devil must have gone past the cemetery gate and run into the bridge, or not known where to park and stashed their car on the side of the road before following the embankment toward the graveyard on the hill. The tow truck driver must have seen the emptied car and gone looking for the students who were surely high and seeking the occult for a terrified laugh or two, and now they are all lost somewhere in the fields trying to navigate their way back by satellites that keep misquoting the polestar.

I park behind the new church and tiptoe through its shadow, studying the abandoned car, the idle tow truck, the quiet stretch of road. Although I have been warned about how the town feels about trespassers, I assume they must know the appeal of this place, this acre of grief that supposedly the pope will not fly over. Tonight is one of the two nights a year that a stairway is rumored to open up so the devil can come up out of the back passage to hell and visit his son, buried for some unknown reason in a roadside cemetery in eastern Kansas. The church sign reads: we meet everyone for a reason. either they’re a blessing or a lesson. If I meet the devil on his pilgrimage to grieve tonight, I don’t know which one he will be. The quote has all of the spectator’s smugness over someone’s new grief, how sure they are that—with time—this suffering will take on the appearance of a plan.

II.

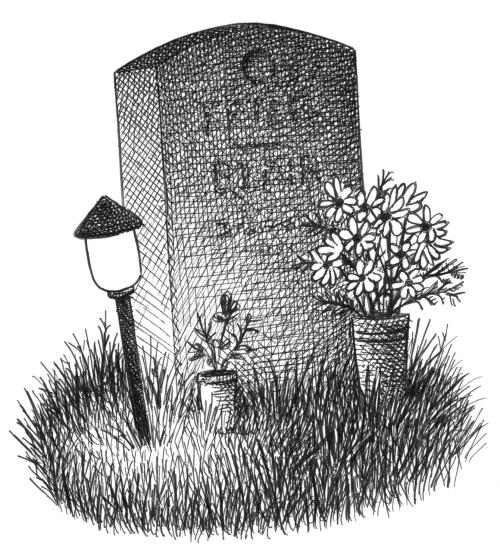

With time, suffering begins to look like a plan, a door closed but windows left open, or so many people reassured me with condolence cards bearing the static flutter of butterfly wings and hummingbirds. When my mother died, my sister and I went shopping for headstones in the cemetery we’d chosen for her burial. Our grief specialist walked us down rows of dead loved ones, solemn, benign in her aesthetic suggestions. My sister, an expert shopper with an eye for color and texture, ran her hand over the buffed granite of strangers’ names and considered fonts before a new monolith would catch her eye, and over the softened mounds she’d bound to get a closer look at the mottled grays and roses within the stone. She ended up choosing a heart-shaped stone, which I found garish, with a vase to hold fake flowers and our mother’s image printed on it, which I also hated. My mother was a devotee of image, though, and I know she would have loved it, if someone can love their headstone.

When I was young, my mother told me some people weren’t meant to survive this life, and I knew she meant herself even though this was before the first time she tried to die. She hated the notion that God presumably had a plan for our suffering, though at times she seemed very attached to hers, always convinced her sensitivity was the same as goodness. I’ve always mistaken strength for honesty with a touch of cruelty. I’ve always been more interested in vices, like the devil, who trespassed in Eden. Like my misdemeanor tonight, how I choose the forbidden even though a sign on the fence warns me I’m not welcome in the cemetery. Part of the chain link has been cut down so an intrepid devil enthusiast could use it as a foothold, swing their other leg over, and drop in. Anxious about the light from the new church, I follow the fence line to a gap where the chain link ends and a barbed wire fence begins. There is an opening and enough darkness to hide me.

III.

Once through the opening, lights illuminate and change the darkness of gravestones I try to hide behind—obelisks leaping into sight from behind trees, the polished granite of upright headstones catching and throwing the light like black mirrors. My boot heels sink into the soft earth, and I apologize in my head to whoever’s rest I am disturbing and to whatever animate shadow governs the quiet of graves. New gifts sit around some headstones that I don’t remember from my last visit. The geraniums look real this time, and a solar light warms the circle of grass around its stake with pale-white glow. A car passes, and I stand against the fence, hoping my stillness is also a darkness. Getting closer to the ruins of the old church also means getting closer to the light at the top of the hill. One of the warning signs that the devil is near is if you see an extra window in the old church, but it’s rubble now, and no one seems to know how it was destroyed.

Although my mom raised me to fear devil worshippers, she didn’t talk about the devil much. She would read me stories of ways satanic parents would torture their children—burning them, locking them in closets, leashing them in basements and letting others hurt them. Now that I have a son, I recognize some of why my mom might have told me these stories. I know why a child makes you more vulnerable to the world and the randomness of tragedy, why it could be important to believe that evil has a master plan and knowledge can protect you from it. Now I also know the ways my mom was hurt as a child and the reasons someone else’s pain might have appealed to her—to not be alone in suffering, to know your hurt was not as bad as it could have been. One man who hurt her said it wasn’t a sin because he was a man of God. When he was dying, he called and asked for forgiveness. I know she gave it, and I resented it, though she said, “finally, finally,” as if all that waiting for his remorse was worth it, and she died so soon after—her heart lighter, graced and ready for resurrection.

IV.

The second time I try to visit a remorseful devil visiting his dead son, I’m ready, traveling on a Sunday afternoon, my heart light as grace in my chest. Earlier, at brunch, a woman told me she and her friends in college would get high and go to the cemetery to meet the devil too. She’d heard that other students had seen a burning man running through a field, but when they stopped the car to help, the man vanished. Supposedly the church had a staircase, and if someone went down the basement stairs, nothing would happen, but when they came up, a week or months would have passed. Maybe this means that the devil’s visiting his son’s grave twice a year really feels to him like visiting every day. Or perhaps it was only something college students tell each other to heighten the pleasures of their fear, the whispers in back seats as they passed each other a joint, coughing and sinking into the nylon and wondering about the nature of time.

I study photographs on my phone of the old church, which was destroyed under mysterious circumstances in 2002, so I could memorize where the stairs used to be so I can stand above them and see what happens to time. I find the foundation slightly hidden in overgrowth, but I don’t know why I didn’t notice it before—the rocks and dirt piled on the square foundation like a grave before it’s healed by grass. I crawl in between the tall bushes and spindly trees—the only kinds that grow on the prairie—and find a rock to sit on among the ruins. There are broken bottles between the crevices, a single flip-flop, a desiccated cicada on its back with its legs drawn in. The sun has bleached the cool mountaintops on beer cans, and the ribs of dead leaves have gone gray and curled into themselves.

I didn’t come with a plan, so I don’t know what I’m waiting for—the rocks won’t magically transform themselves into stairs; a devil with red abs and a cape won’t appear before me; a burning man will probably not streak across the field behind me; and yet, in the pasture just beyond the ruins, above the twists of barbed wire, a turkey vulture turns a slow circle. I want to think it’s an omen, but this is the girl in me, the one who wanted to be brave enough to say Bloody Mary three times in a bathroom mirror in the dark, but just like my girl self, I don’t have the courage. I hadn’t made a plan to tempt the devil to me, so I try whistling, which is supposed to summon him, but it seems I bore the Prince of Darkness and can’t tease, plead, or wish his presence with music, though I thought he might love me for the quality of my suffering.

V.

I wish someone had asked me before I got married how the man I loved suffered. I knew he suffered the way my mother did, confused his sensitivity for goodness, but I thought now I knew how to use my love to fix someone. I used to think that if I had loved my mother in her childhood, I could have helped her. As an adult it seemed so far past that already, my sister rescuing her as she hid in grocery aisles when the panic crept in, counting my compliments when I came home to make sure I loved her, prompting moments for hugs, for touch. Sometimes I fear I see it in my son, this insistence on helplessness, though he is just a boy, an episteme in progress, soft clay for my words and actions, love’s gentlest obligations. I have it, I think, the chance to love my mother as a child, to correct her suffering under my heart’s cautious leadership.

“I miss you,” I say aloud, and I mean my mother, though I think the devil might mistake it for a message for him. It’s not regret I feel as I sit in the rubble of a destroyed church, waiting for the devil to come talk to me about the sufferings he designs; it’s the clean sadness of acceptance. Dragonflies flick their wings and then chase each other among the tall grasses, and a calm emptiness sits in me like yesterday’s light still warm inside the rock. A wasp and I study each other on our separate stones, but this is not an omen either. I don’t have the kind of innocence that could summon a serpent, and I don’t share the same grief as the devil.

As I leave the cemetery, I see two men in chairs in the garage across the road, both with a beer in hand. They look like father and son—the father with a white goatee, the shirtless son tattooed with an eagle and a word in a gothic font. I do not wave; I don’t want to disturb the devil as he visits with his son.

VI.

The first time I try to visit the devil, I bring my son. June warms the roadside graveyard, the first cemetery my son has visited. He does not know what the headstones signify, so he dodges between the small American flags and pinwheels spinning in the hot Kansas wind as I search the names and dates on the stones. False dogwoods and sunflowers, hibiscus and lilies shock the gray stones with their synthetic brightness, bought for their color’s endurance at the Dollar Tree down the road. My son chases down the blooms that have gotten loose and tries to find the settled grave that hosts the matching bouquet with a green plastic nub that lost its flower.

My son gambols down the hill in his Wizard of Oz T-shirt and camouflage shorts, pausing every few feet to complain about rocks in his shoes before resting against a gravestone and emptying them. He loves to wear camouflage because he believes no one can see him if he holds still. I look for the oldest graves as my son collects more fluorescent pink roses to restore to their stem. Lichen wools over a grave marker; moss fills the bellies of the nineteenth century B’s; and a nylon butterfly circles and circles its solar stake, a false visitation.

Of course there is no marker for “Satan’s Son Lies Here,” but pale pink prairie roses shake between the rows. I don’t know why the whole graveyard wasn’t planted with native flowers rather than have garish clusters of dyed hydrangeas arranged in stone vases, though I know my mom’s graveyard has rules, like a neighborhood association for the deceased. I understand no one wants living flowers on the graves because those will age—the peace lilies will brown and drop their petals; roses will wither one at a time and leave a slimy vase full of naked stems.

I haven’t told my son about God or the devil, though I know my plan to try and give him a heart free of guilt and shame is a foolish one. He runs off down the slope of the cemetery to collect a fake daffodil that’s fluttering against the chain link fence. I go back to looking at the names, doing the math of the lives, imagining the death that might go with each age, with each part of history.

VII.

I trace the letters of a name and age lost to history. I think I’m trying to offer whoever is beneath it the tenderness of becoming a memory. Though I don’t go to visit my mother’s grave, I like to think of the devil here, on a sunny hillside in a small town in Kansas visiting his son. The picture of his grief seems so much calmer than mine, more like the scenes I’d seen in movies of the quiet sadness of a death accepted. Something dignified with a tie, his garnet skin shaded under a dark umbrella. I don’t remember if my son was at my mother’s graveside when they lowered her in, but I remember my ex-husband holding him in the lobby while he screamed all through the funeral. I knew he needed me, or at least would calm if I touched him, as he always did, but I let him be hurt and afraid so I could stare at my mother. But I think this may be parenthood—to give our best love to the ones we hurt most.

Although this place seems abandoned, the pink and yellow blossoms my son rescues from the wind is proof we are not alone, that the privacy of grieving has been conducted among these haphazard rows of stones many times before we arrived. Absences leave evidence. My son starts to giggle and watches me, his hand over his mouth. I can tell by his stillness he believes the magic of his camouflage shorts has worked again, so I play along in this game and pretend I have lost him. I cry out his name and grope the air in front of me as if I do not know I have lost nothing. Before my hands discover him and resurrect him with tickles, I want him to have this moment of belief that he succeeded in his grand joke, his childish delight perfect in its conviction that he’s made his mother believe he vanished into a gravestone.

Landis Blair is the author and illustrator of Vers le Sud (Les Éditions Martin de Halleux, 2023), The Night Tent (Holiday House, 2023), and The Envious Siblings: and Other Morbid Nursery Rhymes (Norton, 2019). He is also the illustrator of the New York Times bestseller From Here to Eternity (Norton...