Snowlight

Not an uncommon winter tale. It goes different ways but always starts the same: Two men, friends since childhood, still young and strong, lose their way in a snowstorm that they believed they could out-ski. Night falls; they don’t return to camp when expected. When the storm abates, friends and strangers band together to look for them.

Sometimes they find them, sometimes they don’t.

This time they do, the men huddled against the collapse of an igloo they had attempted to make. Only one is still alive. The other has been gone for hours, his chest too frozen to attempt CPR. Severe hypothermia has rendered the survivor insensible; later, in the hospital, he will say he remembers nothing whatever of the incident—not the rescue, not the long, black night before, not the outing that had begun with such high zest the previous morning.

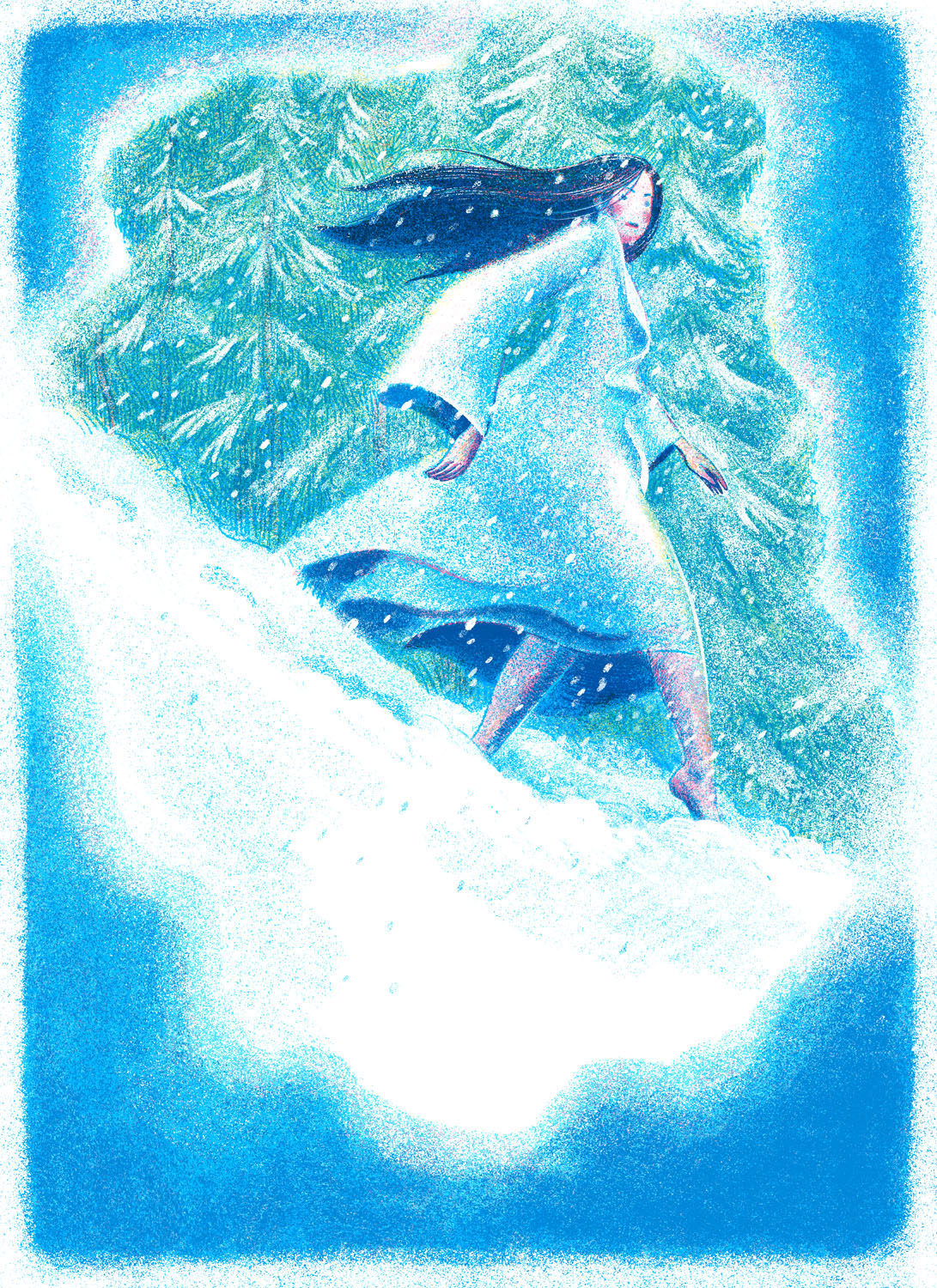

But he does remember something. One thing. Sometime during that night, he had awoken, ignorant of his plight, unaware of the man dying or perhaps already dead next to him, not even knowing his own name. For a while he watched the snow falling through the darkness. He remembers the heavy flakes fluorescing between starless sky and invisible landscape. And a presence, cold but not insensate, a witness to his soundless burial.

He does not mention this in the hospital. He does not tell anyone.

He marries the first woman who does not ask him about that night, who understands his need for silence, who evinces neither surprise nor interest nor pity in the toes he lost or the red frostbite scar on his right cheek, who does not seem to feel ennobled in some way by his trauma. She is, moreover, a beauty, with fair skin and eyes so dark he cannot distinguish iris from pupil.

He is content to remain in the sunlit coastal town where he grew up, a place where it has not snowed for a hundred years. His appetite for adventures far from home has diminished. He will never seek out snow for pleasure again. Still, he loves being out-of-doors, his skin drinking in the warmth, the scar on his face fading to pink, then white. His wife burns easily and prefers to stay indoors. When she cannot, she hides under straw hats and long linen scarves and dresses. Together they raise three children who love the sea.

In all of the stories, the marriage is happy.

In some of the stories, she doesn’t age at all.

In none of the stories does he mourn his friend, the one who did not survive the storm. Not out loud, anyway.

Sometimes the man will stop in the middle of something—hammer poised in midair, a laugh brought up short, a child’s question left unanswered, his body suddenly still while his wife moves above him—and reflect quite involuntarily on the enormity of the close call he survived and the dizzying almost-never-was of now. He cannot hold the thought for longer than a few seconds. He is grateful for the amnesia that leaves the rest of that sad event shrouded and unseen.

And then a cold front presses deeper than it has in a century, and a storm that should bring ordinary wind and rain brings wind and snow. So much for historical weather patterns and forecasting. So much for the safety of forgetfulness. He wakes in the night, alarmed by the muffled howling he has not heard in so long, and opens his eyes to find his wife sitting up beside him in bed. He speaks her name, and she turns to him, her face still luminous, except for those unfathomable eyes. And he suddenly understands that he is not the one who has required silence about the past. She is.

In a rush of sensation, like emerging from the dry cup of stillness behind a waterfall into a violent curtain of water, he remembers everything: the high-fiving as they set off; the sky open and blue everywhere except that gray line in the west; the celebratory beer at the first warming hut; missing the critical turnoff; losing the trail; the first heavy flakes, then the snow falling faster as the light drained away, and with it, the temperature; the clumsy attempt at a snow shelter; the even clumsier attempt at a fire; the indifference of the storm; then waking—waking and watching the snow in its own light, her light, the icy breath she’d cast over his friend, the kiss, the cheek, the burn. He brings his hand to his face.

“Don’t say anything,” she says. Her voice is like winter.

“I wasn’t going to,” he says, although it is not true. He was on the verge of telling her everything.

She smiles at him, and it reminds him again of that night, and the expression, half-amused, with which she regarded him when she decided to spare his life. Only then the amusement had been mixed with pity, and now he sees it mixed with something else—regret, perhaps, or maybe love. Maybe they are the same thing.

“What happens now?” he asks.

She shakes her head. He does not know if that means she does not know or just, No.

He reaches out to her, to touch the lambent skin of her arm, but they both pull away with a start—he from her iciness, and she, he guesses, from his all-too-human heat. Next door, he can hear one of their children stir and murmur in sleep. Outside, the misbegotten snow continues to swirl around the house and against the warming sea nearby. They remain side by side in their bed, the man and the woman, not speaking, and wait for the light of morning and whatever rescue it may bring.

Wesley Allsbrook attended the Rhode Island School of Design. Her work has been recognized by the Art Directors Club, The Society of Publication Designers, the Society of Illustrators, American Illustration, Communication Arts, Sundance Film Festival, Venice Film Festival, Raindance Film Festival, the Television Academy, and the Peabody Awards.