The Summer Kitchen

1.

When Marg lived in the house, there was a whole other house in the basement where her grandparents lived in the summer. They were from Ireland, the McCabes. They were royalty, Marg thought. That’s how she felt about them.

That summer, she treaded lightly on the first floor when the McCabes were in their rooms. Pap McCabe had a thick accent, and she could hardly understand him. But recently, he’d said to her, “Oh, Marg, you’re bright as a penny.” He’d said it for no reason she could point to. She’d been standing out in the backyard, jumping up and down trying to get her mother’s attention on the upstairs porch.

Until he’d said that, Marg was never sure Pap McCabe quite knew who she was. She had one sister, Elsie; one stand-alone brother, James; and the twins, also brothers—every one of them older, bigger, and louder than she was. Also, out in the wide world, more than twenty cousins. These people had only one Pap McCabe, but he had all of them. She’d heard her mother explain this to Elsie once when Pap called Elsie by the wrong name. That would never happen now; everyone knew who Elsie was now.

Marg wanted Pap to keep thinking she was bright as a penny, and when someone mentioned her, for him to think, Oh, Marg—of all the Healy children, she’s the one that’s best, the one that’s bright as a penny. So she stayed away from him as much as she could. This wasn’t hard in summer because he and Mother McCabe stayed nearly all the time down in the basement apartment where it was cool. They didn’t even need to come upstairs to see her mother, as she was often down in their part of the house cooking in the summer kitchen.

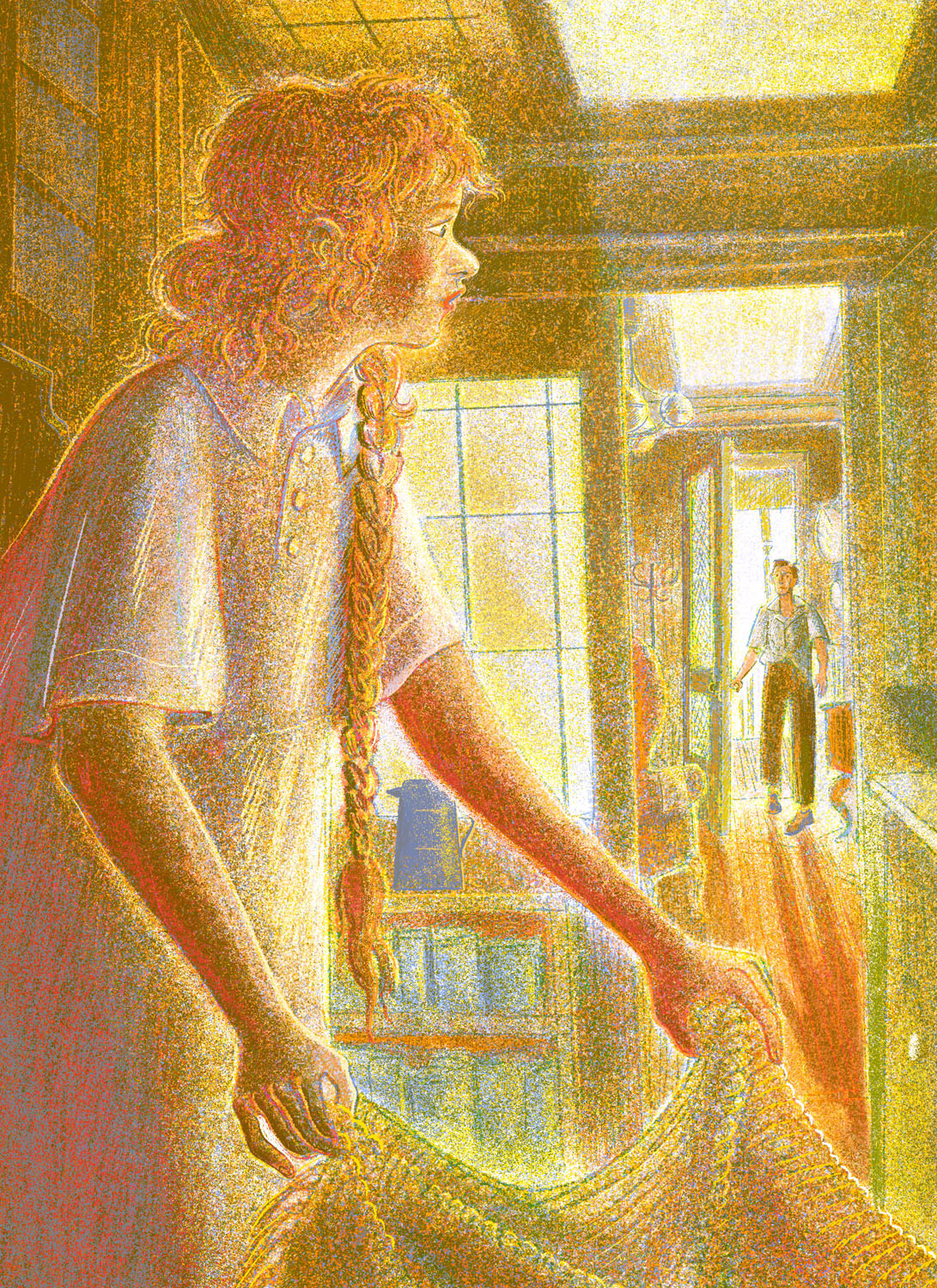

The main business of the house happened on the first floor, in the sitting room and the entry hall. This is where Marg was, folding over a carpet, when she saw the boy on the other side of the screen. He hadn’t knocked, and the sight of him, standing there, looking right at her, no smile or hello, startled her. She dropped the carpet. “Hello,” she said, but too quietly; she wasn’t sure a person could hear that.

There were always boys, grown men, ladies, children—all manner of people, really—from the full stretch of Linden Avenue coming to the house and, most often, just walking right in. Sometimes these were ancient people with such heavy Irish or Welsh accents that, when they spoke, Marg thought they were singing. She was embarrassed when she was finally made to understand that they’d been asking her questions, and were waiting for her to say something.

This boy, though, was not from Linden Avenue, or St. Colman’s School, or St. Colman’s Church. Recently her mother had said that Marg had two ways of operating—she thought things over so much that she did nothing, or she did things without thinking them through in the least and made a mess. A problem with being a twelve-year-old girl, her mother had said. Marg suspected otherwise, suspected this was a permanent and immovable condition, what it was going to be like to be Marg for all time.

In the hallway, she waited and hoped someone would come to tell her what to do. The boy shrugged his shoulders, tilted his head to the side. As if to say, What then, Marg? And then without thinking, she opened the door, and watched him walk right past her, as if she weren’t there.

He had curly jet-black hair and too much of it. He wore a kind of blue work jacket, but it was dirty or had been washed poorly, the color of it drained away in places. His white collared shirt was too big for him. The extra material was bunched up at his chest and brushed against his chin.

She watched him take in the room. It was the best in the house, with high ceilings and big windows. A long couch faced the fireplace. And all along the mantle there were pictures of McCabes, her mother’s family, mixed with pictures of Healys, her father’s family—her family. Marg Healy, Margaret Mary Healy, that’s who she was back then. When she grows up and gets married and leaves the house, she’ll be Marg Thompson, Margaret Mary Thompson. But even after that change, when asked her name in dreams, she will always answer, Marg Healy. And at the very end of her life, when the parish priest comes to hold the final oils over her and to announce in a booming voice to a room filled with her own children and grandchildren, “Margaret Mary Thompson, you are gravely ill,” she’ll think he must be addressing someone else. Another Margaret Mary? She hadn’t met one in a good long while.

Marg said hello again. This time she was sure she was speaking loudly enough. Still, he didn’t say anything. There were voices in the back of the house. He headed that direction.

One look at her downcast eyes would have told him that she was a person of no standing. If he’d have come the week before, she thought, he would have been wrong. In Elsie’s absence, Marg had ascended in the ranks. But Elsie had come home; now Marg was back at the bottom of the heap.

She would have liked to follow him but couldn’t because of the carpets. Her mother had been after her for days. Elsie kept getting her crutches caught on them. Marg had been told to pull up the rugs and take them out to the shed in the backyard. How she was going to do this without running into Pap McCabe she wasn’t sure; the way the house was put together, there wasn’t any easy way to get to the backyard and the shed without going through the basement. She knew she wasn’t going to look bright as a penny dragging an armful of dirty rugs through Pap’s rooms. Seeing her like that, he might say, “Ah, Marg, you’re dusty as a traveler.” And she would have to tell him, “No, I’m bright as a penny. You said I was bright as a penny.” But once it got to that, she knew it would be no use. You couldn’t tell someone you were bright as a penny. They had to think it about you on the spot, or they didn’t think it at all.

She watched as the boy disappeared into the kitchen.

A full year before, during the summer that Marg was eleven and her sister, Elsie, was fifteen, the two of them went to the city pool for a swim. The next morning, when Marg woke up, the house was quiet as church, and her oldest brother, James, was sitting on her bed. She was so surprised to see him there that she was sure she must still be asleep. The house was never that quiet, and James, being eighteen and having a job and a girlfriend, hardly talked to Marg anymore. He certainly was never in her room waiting for her to wake up.

“You done sleeping now, Marg?” James said, and with such kindness in his voice. He said, “Something’s wrong with Elsie. I’m supposed to stay here with you, but I can’t. So don’t you go out of the house until they get back.”

“Where are they?” Marg said.

“The hospital.”

“Everyone?”

He nodded.

“Everyone?” Marg said again. “The twins? Mum and Dad? Mother and Pap McCabe?”

“Yes, Marg. Everyone.”

James got up to leave the room.

Marg looked over at Elsie’s unmade bed, just a few feet from hers. “Wait. Wait. What’s wrong with Elsie?”

“If they find that you’ve been out of the house, they’ll murder me. Then I’ll have no choice. You know I’ll feel gloomy about it, but I will have to murder you.”

“From the grave?”

“Exactly.”

There were always people in the house, always. After James left, Marg went into every room. Instead of the thrill she expected, she turned lonely and missed her mother with a fierceness that surprised her. Several times she went to the edge of the porch wanting to leave the house, then thought of James and stepped back. She didn’t want to cross James. Aside from her mother, he was the easiest person in the house for Marg to talk to. She thought of James, and she thought of her mother, but she didn’t think of Elsie. Back then, Marg never thought about Elsie. Elsie was just there, like the door that led out to the upstairs back porch, or a set of stairs, just Elsie, just her sister.

Marg was sitting in a chair watching out the front window when they finally pulled up in the cars and climbed out and looked all wrong, even the twins, and Elsie wasn’t with them, and her mother wasn’t with them—her mother, the person she wanted most to see. Up the front porch stairs they came, into the house, and it was like a great change in the weather, only it was permanent—Elsie had caught polio.

Now Marg was in the front yard, the carpets piled up next to her, studying if she could fit herself between the fence and the house to get to the shed that way instead of going through the basement apartment.

The front door opened and there was the boy, talking to her. “I was sent to help you,” he said.

“I don’t need help,” Marg said.

He took one of the carpets and unfurled it on the grass. He lay down at one end and rolled himself up inside of it. And then he just stayed there, hidden inside the carpet.

Elsie came outside and looked over the yard. “Where’d that boy go?” She balanced herself over a chair, lowered herself into it, and put her crutches on the floor.

Marg pointed at the carpet.

“He’s in the carpet?” Elsie said.

Marg nodded.

“He’s from West Virginia,” Elsie said. “He told some McCabes down there that he was coming to Pittsburgh to look for work. They sent him to us.”

When Pap and Mother McCabe weren’t living with them in the basement apartment, they were living in West Virginia with other children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren. (Marg had been going through the rolls every so often. Were any of those other girls bright as pennies? She didn’t think so, though she couldn’t be sure. Also, when she really thought about it, she wasn’t quite certain what it meant—being bright as a penny—was it that she was smart or that she was pretty or was it something else entirely? Some good quality she had and didn’t know about but that was easy to see, was clear as day, to a wise and royal old person such as Pap McCabe?)

Marg remembered the way the boy had snubbed her when he first came into the house. She said, “I hope they won’t let him stay.”

“They aren’t decided,” Elsie said.

“He didn’t bring any suitcase or anything.”

Elsie said, “They might call down there and find out about him. He says he has a letter from them in his bag.”

“I told you already, he doesn’t have a bag.”

The boy called out to them, muffled from inside the carpet, “She’s killed me. Or she thinks she’s killed me, and now she’s hiding me in an old rug. Next, she’ll chop me up.” He came unwrapped. He tried patting down his hair and walked over to the porch. He said to Elsie, “How come you didn’t try to save me?”

Marg looked at Elsie, then at the boy, then at Elsie’s crutches—he hadn’t seen them. Elsie’s slacks covered the braces that went down her legs. Marg opened her mouth to say something. But what? She’d never talked about what was wrong with Elsie in front of Elsie. She said to the boy, “Is West Virginia a commonwealth too? Like Pennsylvania?”

He didn’t answer, just kept looking at Elsie. Was Marg whispering again? She couldn’t tell. “And Virginia. That’s a commonwealth too,” Marg said.

Elsie said, “Why would I save you? I don’t even know you.”

The boy said, “So you wouldn’t have to tell the priest. A sin of omission.”

“What’s that?” Elsie said.

The boy said, “When you could have done something good, but you didn’t. You’ll take the same knocks for it as a sin that you did on purpose.”

“She knows what a sin of omission is!” Marg said.

They both looked at her.

Elsie shrugged. “Marg would never hurt you anyway. She’s a company man. Tows the party line.”

“What are you talking about?” Marg said.

“She does as she’s told, and she’s been told not to hurt people. You could get hurt anyway, though, if she starts telling you about some thought she’s having, some theory she’s working on, and all the oxygen starts leaking out of you.”

Marg said, “Elsie can’t save you. She can’t save anyone. She can’t even walk. She has polio.”

Marg braced herself for more sharp words, but Elsie picked up her crutches, matter of fact, and showed them to the boy. Then she pulled herself up and made her way toward the door. She put the crutches out in front, then leaned forward, and used her hips to pull her legs ahead. She’d practiced this at the Watson Home for Crippled Children, where they’d also given her shocks in her legs. She’d written letters home saying that she’d be walking before she got back to Linden Avenue, because of the shocks. Marg’s father read the letters out loud at dinner. But here she was, dragging her feet along the floor. That new sound in the house that had to be heard a thousand times a day, the crutches hitting the floor.

Marg turned to the boy. “They aren’t going to let you stay. Since Elsie got sick, we have to look after her. They turn everyone away.”

He went back to the carpets, opening and then rolling each one up tightly. He picked one up and set to carrying it into the house.

Marg said, “Pap and Mother McCabe don’t like strange people coming into their rooms.”

“I’m not strange, though.” He smiled at her, then opened the door to go inside.

“I mean strange like they don’t know who you are.” She grabbed the end of the carpet he was holding. “We have to find a different way to the shed.”

They went to the side of the house. She pointed out the way she thought might work. He walked ahead of her, turning sideways between the house and the fence, pulling a carpet behind him. She saw how thin he was. He fit through the space just fine. He wasn’t much older than her, Marg thought. Her dress got caught. Her face flushed red, and she felt nervous and hot and thought she might have to take off the dress and crawl out of it. What if she ran into Pap McCabe then? Or what if he came out right now and saw her stuck to the fence?

The boy appeared at her side, carefully pressed his fingers on her dress, away from her, toward the spot where it was caught on the fence, and she was released. He smiled and she saw that, unlike a lot of people with curling black hair, he had blue eyes, dark blue, like the color of the sea in the drawings at the Byzantine church she went to sometimes with the Romanian woman who lived next door.

But she didn’t want to thank him. Would it be a sin not to be polite? The priests and sisters at St. Colman’s School were never polite, certainly not to Marg. Did having a calling exempt you from politeness? She must have been turning this thought around for a good while, because the boy knocked lightly on her head and said, “You inside there? You want to come up out of there and help with these carpets?”

His name was Rory Kelly, she learned at dinner. While he ate, he kept almost getting his sleeves stuck with food. The work jacket was too big all over. The twins had no interest in him. James came to dinner with his girlfriend and their eyeballs were stuck to her. James gave them baleful looks.

To her surprise, it was decided that the boy could stay, and that someone would take him to the bus station to get his bag. He had a bag then? The twins would show him to the extra room. But after dinner, the twins vanished, and the boy was left to her.

It wasn’t really an extra room. It was a Shaker bed set down in an alcove in the upstairs hallway, no windows or even a lamp. They left one of the hall lights on when they had someone sleeping there. Marg showed him the bed and then went to her own room.

The men from the countryside who came to the house most often stayed for a week or two and got a job at the steel mill. Then they moved to a boarding house or in with people they met at the mill. They came back from time to time to say thank you, or to bring a gift, or to show them a baby they’d had. Some people didn’t stay more than a few days before they went back to West Virginia, or Maryland, or the big woods in the middle of Pennsylvania. Those people said thank you a couple hundred times and backed out the door like they’d seen a ghost. Marg’s mother liked those people best. “They know what’s what,” she’d say. “They saw the inside of that mill.”

A few minutes later, the boy was in her doorway looking around. “Probably you got a dead brother or sister.”

“What? Of course not.”

“Dead aunts or uncles?”

“No…I don’t think so.”

“Your grandparents?”

“The McCabes? They were there at dinner just now. They aren’t dead!”

“Your other grandparents?”

“The Healys? They don’t live with us, but they aren’t dead.”

“Was the window open the night she caught the case of the polio?”

“‘The case of the polio’? That doesn’t sound right, that’s not what people say. That’s what they say about a mystery on the radio or a Sherlock Holmes story.”

He touched the glass, then leaned his forehead against the window and rested it there, closing his eyes.

“What are you doing?” Marg said.

He shrugged.

He looked to be praying. Marg said, “It was closed. Elsie always keeps the window closed. When she wasn’t here, I left it open. But she’s back, and what she says goes.”

He turned around and pressed his back against the window. Then he walked the length of the room. He stood between the two beds and turned around facing Marg. “The angel that came into the room and gave her the polio stood here,” he said. Then he looked back and forth between the two beds. “Just a couple feet here between the two of you. Why didn’t he give it to you? Or both of you?”

“You don’t get polio from angels.”

“You must have someone, an angel, maybe a dead relative, directing things around, saying, ‘No, don’t give the polio case to the one in the bed on that side of the room—give it over here to this one.’”

“It’s nothing to do with angels. And she didn’t get it here. She got it at the swimming pool.”

“You were swimming too?”

“No,” Marg said, though she had been. In the pool, she’d floated alongside Elsie and Elsie’s friends and then watched them from the sides. Remembering now, she’d swum several times to the bottom of the pool and looked up. Elsie had a new dark blue swimsuit, with a white and blue skirt. You couldn’t miss it. From the bottom of the pool, looking up, Marg had seen Elsie’s legs going back and forth, back and forth.

The boy opened the window the whole way and leaned out. “You know that music coming up from down there?”

“You’re going to get me murdered if you don’t close the window.”

It wasn’t music from a radio. It was something like a band, practicing. Marg could hear them quite often. The houses where the music came from were pretty far away, but the music carried up the walls of the ravine. The band stopped just then, then started up a different song. As far as Marg could tell, all they did was practice and play pieces of songs. She said, “It’s the poor that live down there. That’s what Pap McCabe calls them, ‘The Poor,’” and she mimicked the long pitying face that Pap made when he discussed such things.

“Ah, ‘The Poor,’” the boy said, and he made the long face too, longer than hers. “A sorry batch of humanity.” He leaned out the window again. “Did other people that were swimming at the pool catch the polio?”

“No,” Marg said, though she wasn’t sure. They closed the pool for the whole summer because of Elsie. It had made Elsie something like a famous person, at least for the rest of that summer. Everyone talked about her all the time.

Marg could hear Elsie coming down the hall. The crutches hitting the floor. “You better go back to your room,” Marg said.

Then Elsie was in the doorway talking to the boy. “You know that Rory Kelly is the name of a famous Irish boxer? The best one around here, anyway. Maybe you’re related? There must be a lot of Rory Kellys, though. There are probably even other Rory Kellys that are boxers who aren’t famous yet, and now they never will be because he’s the famous one now. If you wanted to be a boxer, you should just drop it.”

Marg said, “Do we have a dead aunt or uncle?”

Elsie said to the boy, “Or you could change your name. Though it’s a righteous name for a boxer.” She put her crutches down and sat on her bed. “I don’t really know that much about it, boxing, but I read the newspaper every day at the Watson Home. Even the advertisements and the business part, and the stories about the baseball players and all that. I read all the stories about Rory Kelly.”

Marg said to Elsie, “What about, do we have a dead cousin?”

The boy stood up tall and said, “I am the Rory Kelly.” He put his hands up in fists and danced around in the little space between Marg’s and Elsie’s beds, throwing punches at the air, ducking from his opponent. He did it for the longest time, until his face started to turn red, but he wouldn’t let up. Finally, Elsie laughed, then he stopped, stood up straight and still, and smiled at her.

“‘The Poooor,’” Marg said, stretching out her face. But neither of them looked at her.

It wasn’t really that Marg liked the music that came up from the valley, not exactly. Before Elsie got sick, her father had a practice of reading to the both of them, a few pages from the lives of the saints at bedtime. In these stories, there were often flaming pokers, or pieces of hot metal used to pull the flesh from the ribs of a perfectly nice person.

Or, sometimes, if her father had to work late, Mother McCabe would come all the way up from the basement to tell a story, things she made up, things she said she’d seen growing up in Ireland. She’d lived on a farm by the sea. Her stories were more welcomed by Marg, but they too would deposit strange, unsettling pictures in her head—a pair of riderless white horses running down an empty lane; a fish turned into a man and then back into a fish; a pile of strawberries in a field of snow.

Sometimes the music could make a distance between those stories and her sleep and dreams. She’d lean out the window and listen for a while, and it would seem to wipe the pictures away.

In the night, Marg went down into the kitchen to get Elsie a glass of water. On her way back, she stopped and tried to get a look at the boy. A flash of white. He was taking off his shirt and getting into bed. He had birthmarks all over his back; she could see because of his pale skin.

When she got back to the room, she told Elsie about the birthmarks.

“What do they look like? What shapes?” Elsie said.

“I couldn’t see. The hall light isn’t bright enough.”

“We’ll have to think of something to do to get him to take his shirt off.”

“What? What are you talking about?”

“Keep your head together, Margaret Mary,” Elsie said. “I’ll think of something.”

Marg knew you didn’t get polio from angels. Still, she spent a good deal of the night haunted by the thought of an angel turning away from her and toward Elsie. Also, she found appealing the notion that some unknown relative, some dead relative, a newly minted angel, was about the house, protecting her. But why wouldn’t that angel also protect Elsie? The boy was muddying everything, even angels.

It was Sunday the next morning. Everyone was set to walk to church, except for Elsie. She said she was tired, but Marg knew she wasn’t—she just didn’t want to go to church. Marg tried to get her to say so, but Elsie turned away from her and looked at the newspaper.

When they got to church, Rory Kelly wouldn’t sit with the family. He wanted to stay in back and converse in private with God, is what he said to Marg’s mother.

When Pap McCabe’s head nodded over in sleep, Marg excused herself to go to the bathroom. Her father gave her a dark look, and she almost backed down, but she wanted to see the boy, wanted to know—What did he mean “converse in private with God”? Probably he meant he wanted to smoke a cigarette on the steps outside, and if that’s what he meant, she wanted to see it with her own eyes and tell her mother.

The walls along the sides of the church were crowded with little wooden rooms for confession and statues of hunched-up saints with hollowed-out eyes. Walking past them, Marg felt they could hear every clack of her church shoes.

Rory Kelly was in the last row, and though it was the homily by then—a stretch of the mass when you’re meant to sit in the pew and listen—the boy was on his kneeler, his hands clasped, and he was really, it seemed, conversing with God. What she did in church, she’d suspected everyone else of doing, which is to say that she kneeled and closed her eyes, but not to talk to God! She only did it so no one would notice her.

On the walk home, to stay away from Pap McCabe, Marg walked behind the family. She saw that Rory Kelly was trying to talk to the twins. They pushed him off the sidewalk into the street. He came back and walked with her.

“You have those angels all wrong,” Marg said to him. “Do they keep you from getting polio or do they give it to you? It can’t be both ways at once.”

“The chief creatures of God are angels and men,” he said. That was from the Baltimore Catechism. She waited for the rest. But he paused for a minute and shrugged. “They are so big, anyway, those angels. You won’t believe it, because they step so lightly.”

That wasn’t from the catechism; he’d made that up. But he said it in such a convincing way that she wasn’t sure what to say back to him.

She stopped walking and watched them all stream far ahead of her. James out in front, the twins, the McCabes, her father, and her mother. Marg saw that her mother was stooped over and leaning forward like she was walking into a strong headwind.

The thought occurred to Marg that, whatever it was that happened that night, the work of angels or not, she’d slept through the worst moment in the life of her family—the moment when Elsie woke up and couldn’t move her legs. Elsie had wanted a glass of water, and she sat up to go downstairs to get one and found that she couldn’t move her legs. She’d stayed like that for a while, confused, then she shouted out for someone. And Marg had slept through even that. After a full day of swimming and piercing sunshine, she’d walked that night into a black corridor of sleep and, unlike Elsie, woke up the next day—unchanged.

The boy’s bag wasn’t at the bus station. Marg’s father and Rory Kelly came into the kitchen where Marg was sitting with her mother and Elsie getting dinner ready. Someone had taken the bag, Rory Kelly said. His mistake, he said, being from the country and the woods of West Virginia, he hadn’t thought to put it in a locker or anything.

After dinner, Elsie said, “We’ll have to find you something, at least a shirt. Let’s go into James’s clothes. He’s at work all the time. He’ll never know.”

“James is bigger than me by two times.”

“It won’t be any bigger than the shirt you have on,” Elsie said. “And it will be clean at least.”

James’s room smelt strongly of cologne. Rory Kelly coughed.

“It’s disgusting, isn’t it?” Elsie said. “His girl makes him wear perfume to cover the grease smell from the restaurant where he works. Let’s see if he has any white button-up shirts.” She sat on the bed, directing them around the room with her crutches.

Marg pulled down a shirt, undid the buttons, and handed it to the boy.

“You better try it on in here,” Elsie said. “If the twins see us coming and going, they’ll tell James.”

“And he’ll murder us,” Marg said.

The boy turned around all the way into the closet and closed the door. A minute later, Elsie tossed a crutch on the floor, and it made a big crashing sound. Rory Kelly jumped into the room. “You okay?” he said to Elsie. He seemed to remember that his shirt was off, touched his arms, and then turned quickly back around and shut the closet door.

“Marg, you’re a moron,” Elsie whispered.

“What?”

“Those aren’t birthmarks.”

But Marg hadn’t been looking at the boy, she’d been staring at Elsie. Elsie always wielded her crutches with such care, it had given Marg a jolt to see her throw one like that.

Out came Rory Kelly in James’s shirt. He looked pale and too thin swimming inside of it. They’d never hire someone so slight at the mill. Did he not know that? Had anyone explained that to him?

“While you’re wearing that one,” Elsie said. “I’ll have Mother McCabe wash your shirt.”

The boy sat down on the floor and stared at his shoes.

Marg said, “What’s wrong with you? You got a nice new shirt now.”

Elsie kept staring at the boy. She said to him, “You know, when I was living in the Watson Home for Flopping Limbs, I’d wait until the night nurse fell asleep, and I’d wheel right out of my room. The night nurse was a heavyset lady who slept like a dead whale.” Marg noticed that the boy had stopped sulking and was now looking at Elsie.

“My bed had wheels,” Elsie said. “I could push it slowly and glide through the hallways like a low-flying crop duster. I’d look in at all the children that had it worse or had it better than me. At the end of the hall was the room with all the people sleeping in the big submarines getting oxygen pumped into them. Inside one of those was the girl who was made to walk down the aisle next to me at my confirmation. She always said that, when we got up to the altar and were meant to kneel and kiss the bishop’s ring, she was going to pull the ring off and make a run for it. I couldn’t think straight the whole mass worrying she was really going to. I mean, she was just the right kind of person for that job. I didn’t know which submarine she was in. I’d just look through the window.”

That was the first time that Elsie had talked at much length about the Watson Home since she’d come back. In their room that night, Marg thought Elsie was asleep, so she opened the window and leaned out to hear the music. But Elsie was awake. “I hate that infernal racket,” Elsie said. “Shut the window.”

Marg did as she was told. “Is that girl dead now, do you think? The one that was in the iron lung that was going to steal the bishop’s ring?”

“How could a girl that smart and steely die? There’s no way,” Elsie said. “And if I’m thinking about her, she’s not dead.”

“What’s that mean? Is she dead or what?”

Elsie didn’t answer.

Out in the yard the next night, pulling apart corn for dinner, Marg’s mother gently said to the boy, “Were you out taking punches like that other Rory Kelly, the boxer?”

Marg recognized the tone in her mother’s voice, like a note in a song. This was the sound of her telling you a thing you didn’t want to be told but telling you in such a way that you had to listen. How was it that her mother knew how to do everything?

The boy shook his head.

Marg’s mother said, “Even a big heavyweight takes a slug from time to time.”

He glared at Elsie. Then he looked straight ahead at their mother and held her gaze.

“You came into some trouble?” she said.

“No trouble,” he said. But he set the corn down in front of him. Everyone stopped what they were at. Marg felt that something was underway, but she didn’t know what.

Her mother said, “Marg, go and help your grandmother with dinner.”

“What about Elsie?”

“Margaret Mary,” her mother said.

She walked into the McCabe’s apartment and into the summer kitchen. It was empty. Mother McCabe must have been cooking upstairs that night. Instead of going up to help, though, Marg hid down behind the counter, then moved slowly up so that she could see out the window that was above the sink. The boy was headed to a dark corner of the yard, and her mother was following him.

She heard something shift in the room and turned to see that Pap McCabe was right behind her. “Marg? What you doing? Oh, I see, I see. It’s you, then, that’s been thieving the cake? Sly methods, yours.”

“What?”

Then Pap gave her his long pitying face, the one he made when he talked about the poor. He opened the cupboard just next to her: Inside was a Bundt cake on a glass plate. “They’ve been shrinking all summer. A great mystery. But you think Mother McCabe don’t have a doctor’s degree in the detection of stolen cake? She could see there’s someone making cuts on opposite sides of the hole, then pushing the cake together. Just the circles in the middles were evaporating like. She wasn’t sure who was the culprit.”

“It wasn’t me.”

He shook his head, then looked out the window. He said, “Mother tells me we got to mind our own business down here.”

“I didn’t steal any cake! Must have been the twins. It wasn’t me.”

Pap appeared not to hear.

“Elsie can tell you. I’m a company man.”

Pap was still looking out the window. Marg looked out too. Her mother had brought the boy back to the patio and they were standing under the lights now. They were not birthmarks, those shapes on his back. Instead, bruises, like nothing she’d seen before. Great rounded fields, purple and black and green. She was not bright as a penny. She was a moron, like Elsie had said. She felt she’d misunderstood something that would have been clear to anyone else. Also, she had not taken any cake. Pap thought something wrong about her, and she could see there was no going back.

“What’s the problem now?” Pap said. He put his hand on Marg’s head. Then he wiped her face. She hadn’t realized it, but she’d started up in tears.

Everything changed when Elsie went away, then changed again when she came back home, and now changed again—the presence of something beyond her understanding in the house. Elsie’s polio, then Rory Kelly, and now his bruises, which also seemed to bring inside the house whoever it was that gave those bruises to him.

That night, Marg’s sleep was fitful. She woke up sweating and saw that it was late in the morning. She dressed and walked down the stairs. The family was all in the living room having some kind of conclave. Outside, Rory Kelly was sitting alone on the front steps. She sat down next to him. “What happened to you anyway?” Marg said.

“A farm animal got wild mad at me.”

“What kind of farm animal?”

He shrugged and pulled his work coat closer around him. She saw that he’d put his own shirt on; it was yellowing at the collar. She thought to ask what he’d done with James’s shirt but decided against it.

All the other kids from Linden Avenue were out in the street. In the windows behind her, she heard the McCabes in the front room talking to her parents and Elsie. The front windows were opened. It seemed they were going to make a phone call to West Virginia, to see who knew the boy and find out what had happened to him. But which McCabe they would call, they couldn’t decide.

“I’ll be right back,” she said.

She went down into the summer kitchen and took two slices of cake. Pap McCabe thought she’d done it, so she might as well have done it. Though, it must have been the twins. It was over, Pap thinking she was anything special. She wrapped each piece up in wax paper. Then she went back out to the front porch and walked past Rory Kelly out to the sidewalk. “Come on,” Marg said to him.

The two of them perched on the bending lawn in front of a neighbor’s house. They sat in silence and ate the cake.

Then the boy stood up and said for Marg to follow him. They walked up Linden Avenue to the end, crossed a few more streets. “Where are you off to?” Marg said. She followed him into a patch of woods where there was a set of stairs set into a hill. Dogs barked then trotted out from the sides of the hill, sniffed them, and went away.

The trees got thicker. The houses stuck into the sides of the hill seemed to disappear behind the trees. Marg’s legs started to burn up from all the climbing. She stopped. As soon as she did, the noise of her shoes hitting the steps disappeared, and she could hear her father’s voice, echoing up the hill. “Marg!” he was yelling.

“Wait,” she said. But Rory Kelly didn’t listen. When they got to what she guessed was the top, the end of the stairs, there wasn’t much there: a small meadow, a metal bucket where people burned their garbage. “What is this place?” Marg said, feeling a little afraid and also disappointed; she was hoping for something better after all that walking. The boy carefully put his hands on her shoulders and turned her around away from him, toward an opening in the trees, then he let her go. She saw that she’d been facing the wrong direction. Now, in front of her, was everything—her whole neighborhood and, out farther, the tops of the tall buildings all the way downtown, the smoke pouring out of the mill, going up and up. But closer, her neighborhood, piled with steeples. How different, almost unrecognizable it was, as if he’d taken her to a foreign country. When she was down on Linden Avenue everything was houses, houses, houses, St. Colman’s School, St. Colman’s Church, backyards, the porch in front of the house, the upstairs porch in the back of the house. But from here, everything was trees and bell towers, steeples, neatly arranged shingles and roofs. It all appeared, to Marg, surprisingly grand.

While she was thinking all of this, the boy was standing next to her. He’d known that she’d like such a thing as this view. But how? She hadn’t even known that herself. Then another thought. Marg said, “How did you know this was up here?”

“I just know things.”

“But I didn’t know it was up here, and I live here.”

They faced each other. Marg could hear her dad shouting from down the hill. The boy’s face had turned pale, and he looked sad, angry, jealous? Marg couldn’t know. A live electric wire seemed to come loose in her stomach.

She’d think of this at the strangest times, this moment, the boy’s face, the afternoon Pennsylvania sunshine angling through the trees. He held her gaze for the longest time, as if he were about to say something, to tell her, perhaps, one way or the other, if she was a good or bad person, bright as a penny, worth anything. Or maybe he’d tell her what had happened to him. But then he walked away.

“Where are you going?” Marg said.

He went through the trees and down the other side of the hill.

She was all alone. They were shouting for her, not just her dad, now her mother and the twins. She stood listening to them, looking at the place where he went into the woods.

2.

A book was open on the table in the school library on an afternoon when Marg went to pick up one of her grandsons. A book about Ireland, mostly photographs. She turned the page and saw the same statue that leaned over the door of her church growing up. St. Colman, his long wavy hair. She read in the book that this was a cathedral with his namesake at the edge of Ireland. Often this cathedral was the last thing people would see from the ships as they left. Their last sight of home. Pap and Mother McCabe long dead by then, and no one else to ask. Was it the last thing they’d seen? And why had no one told her about this?

Things came back. St. Colman, there he was with his staff and miter, and his spooky eyes. That was him all right. Other things too. Her brother James, for one, after a long absence. He married the girl he was dating that summer, and that girl had not cared for Marg. Years passed when they did not see each other. Then, at their mother’s funeral, James got up to say a bit of eulogy and he broke down into pieces. He couldn’t read even the first word. He just stood there looking at the paper, shaking. Up Marg’s husband went. He guided James away from the lectern to their pew. Marg took James’s hand and held it while he wept. Their grief, she could see, was equal. Their siblings would go on as before, but not them, she knew. They’d been done in.

Afterward, at the wake, Marg refused to help Elsie and the twins with the caterers and the guests. She and James sat at a table in the backyard and plowed through the whiskey. Her brother, restored to her.

Things came back: James, St. Colman. Though, not everything. Not Rory Kelly.

She made the twins walk with her up those winding stairs to the meadow lookout a few times, but they never did see him. Of course, his name wasn’t Rory Kelly. He wasn’t from West Virginia. He’d never met any McCabes until he’d walked into their house.

She was to take her grandson to see a special dentist in downtown Pittsburgh, an hour’s drive from where she lived now. This is why she was in his school waiting for him, looking at the book with the photograph of St. Colman’s Cathedral. She had not been to Linden Avenue or anywhere near the old house in many years. After her mother’s death, she couldn’t bear it. She’d made Elsie and Elsie’s husband take care of everything, removing their mother’s possessions, selling the house.

The drive to the dentist’s office did not require her to go through the old neighborhood, but it wasn’t exactly out of the way.

As they got closer, the streets and their names started to get familiar and Marg drove slower and slower. At the intersection where she would need to turn if she really was going to drive down Linden Avenue, she stopped, undecided.

“What’s happening?” her grandson said. He was ten.

The person in the car behind her beeped, then drove around her.

“Nothing,” she said. But she still didn’t put her foot on the gas.

She had a good number of grandchildren. With this one, though, she sometimes had a sense, or maybe more of a hope, that if she met him at a bus stop, they would have become lifelong friends. He called her sometimes at night to talk to her about things that had happened to him during the day. He was bright as a penny, she liked to tell him.

“Do you want to see the house where I grew up?” she said.

“Oh, definitely,” he said.

She turned down Linden Avenue. So changed, and yet it was as if the numbers on the houses and the names of the side streets were stitched within her, indelible. She told her grandson the names of the families who’d lived in the houses they passed, and what kinds of people they were. Generous people, mostly, or very funny people. Or people you had to be careful around for one reason or another.

When they reached the house, her house, it was much smaller than she remembered. That was to be expected; houses were bigger these days. But really it was quite small. They must have been shoehorned in there, especially in summers with Pap and Mother McCabe, though it had not felt like that, not to Marg.

Rory Kelly’s real first name was Emil. She found it written in pencil on a half-completed job application he’d left back in the alcove. Her father took him for his word, that he’d come to town to get a foothold, and must have set to helping him find work. But the boy hadn’t even written in his last name. For the address, he’d written the address of the house on Linden Avenue.

After he left, the family stayed together for the rest of the day, even James, as though some outside threat had come and gone, and banded them all together. They’d called the McCabes down in West Virginia. None of them had met him or heard of him. And this was what had set Marg’s family out looking for her and the boy that day.

He’d made up a story and snuck into their house, a stranger. What a thing to do. They spent all day talking about him, piecing it together. He’d seen the name on a piece of mail? He’d read about Rory Kelly in the newspaper and, finding himself in an Irish household, pulled up the only Irish name he could think of? Her father and her brothers checked to make sure that the silverware was all intact, the liquor, the little bits of money and change in various bureaus. Her mother kept insisting that he wouldn’t have stolen anything, that he was out looking for a safe harbor, some solace. She would not participate in the checking of the silverware. She didn’t care about silverware. Her mother would never say a bad thing against the boy. Once at church, months later, she leaned into Marg and said, “Pray that that boy found a port in the storm.”

They ate dinner late that night, at the picnic table in the backyard. They didn’t speak of him at dinner. They’d run out of things to say. After she was through eating, Marg left the table, went and lay down in the grass. She watched the tops of the trees blow around, a kind of roof opening and closing over the yard. She listened to them talking. Pap McCabe sang a little Irish song that made her mother laugh, and her mother laughing made the twins break out laughing. They did this all the time, laughed until they couldn’t breathe. At the end of it, one or the other of them would lie pale and heaving on the ground having frightened himself from laughing too hard. Her mother leaned over and smiled at Marg, as if, in the wide world, only the two of them understood everything.

In some ways, the most surprising thing was that the house stood, solid, real, and here right in front of her. So much of her childhood seemed ephemeral. Also, by now, distant—further and further away. Though of course, sometimes her childhood felt quite close, as if she were still locked inside its puzzles.

She thought of the staircase hidden in the trees, her burning legs, the view, Rory Kelly. He slipped into the house, then disappeared into the trees, but he’ll stay with her to the last.

She’ll think of him, of something he said to her, in that final room, the parish priest leaning over her. When the priest says to her, and so loudly, “Margaret Mary Thompson, you are gravely ill.” After a while, a few minutes to think it through, she’ll sit up and say, “No, Father. You’ve got it wrong. It’s not me that’s ill. It’s Elsie. It was decided among them, the angels.”

“Why are we stopped?” Marg’s grandson said. “Is this the house?”

(Marg isn’t wrong about this grandson. They’ll be close for the rest of her life. He’ll be there with the priest and his clutch of oils. By then, he’ll be a grown man, and among all that full room of people gathered there, it’ll be him with the presence of mind, the straightforward devotion to his grandmother, to step forward and close her eyes for the final time in this world.)

Marg took in the old house, the small porch, the short windows, the crooked fence. “No,” she said.

She pointed ahead, a few houses up, to a larger home, with a wide porch. “There,” she said. “That’s my old house.” A Welsh family had lived there; a family that had sailed through those times. A house untouched by illness.

Wesley Allsbrook attended the Rhode Island School of Design. Her work has been recognized by the Art Directors Club, The Society of Publication Designers, the Society of Illustrators, American Illustration, Communication Arts, Sundance Film Festival, Venice Film Festival, Raindance Film Festival, the Television Academy, and the Peabody Awards.