Silent Hero

My grandfather never spoke about his experiences in World War II. After he died, I set out to reimagine them.

RIGHT: Volgograd Region, Russia, 49°02′46.8″ N, 44°08′08.6″ E, January 31, 2022.

In my photographic practice, I work with various technologies in order to engage with certain histories. For years now, I have been focused on a particular history—that of my grandfather, Grigoriy Lipkin, and his brother, Naum, both of whom served in World War II. The technology, in this case, is generative AI, which can be used to create deepfakes, often for nefarious purposes. Instead of leaning into the surreal accuracy of deepfakes, however, I explored the creative potential of AI’s inaccuracies, reinforcing glitches and imperfections to arrive at a different type of image that photography can’t offer—an image from where a camera can’t go.

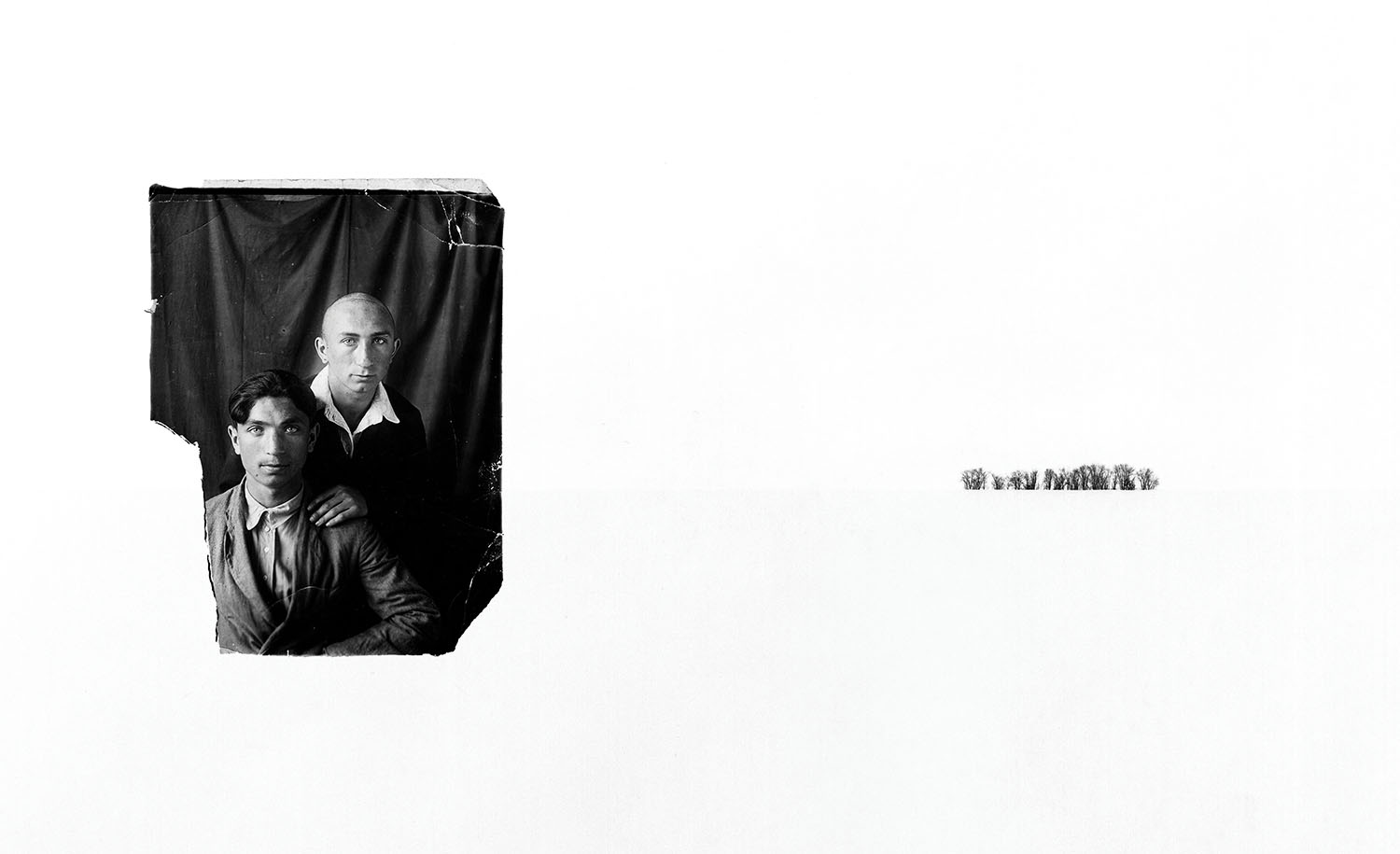

My upbringing in Moscow reverberated with echoes of World War II. What was arguably the worst conflict in human history had irreversibly impacted nearly every family in the Soviet Union, including my own. Growing up, every year on Victory Day I would visit the new monuments commemorating Soviet triumph with my grandfather the war hero. He would solemnly watch me clamber over the commemorative tanks, warships, and planes like a jungle gym before we continued on to the plaques in memory of fallen soldiers. Engraved in granite or marble, the list of names seemed endless. I watched him scan them, line by line, stopping at the letter L for Lipkin—looking for his brother’s name, to no avail. Naum Lipkin disappeared shortly after being drafted in 1941.

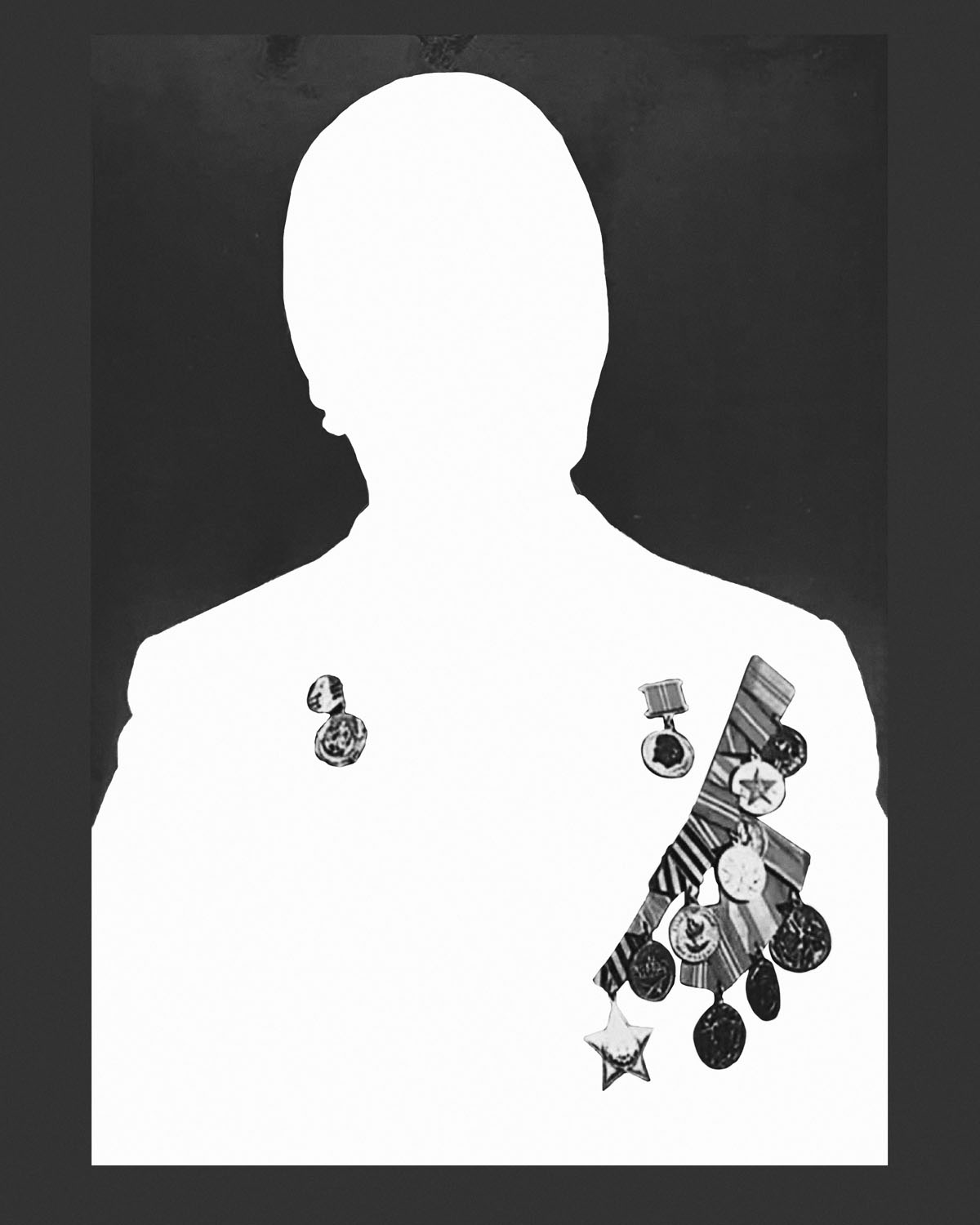

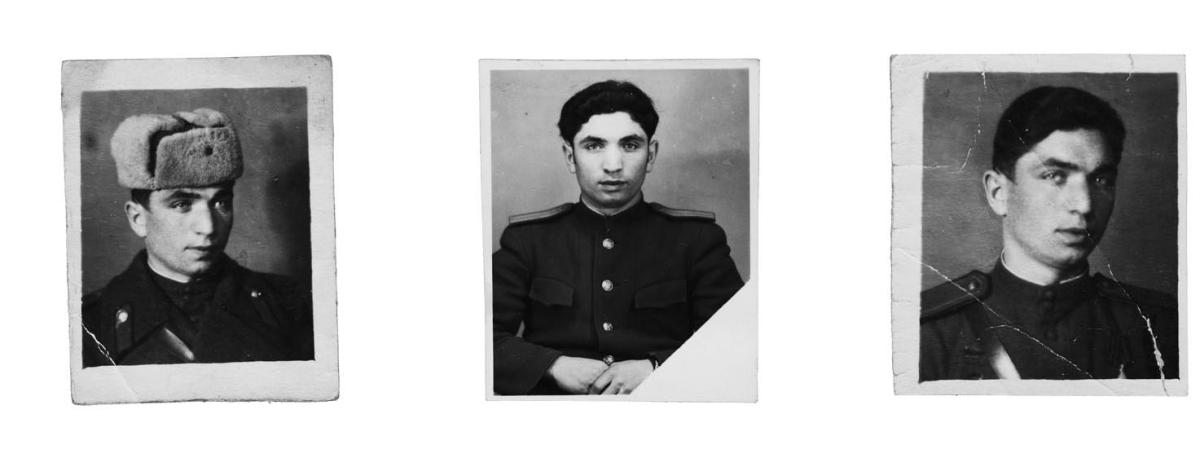

Grigoriy joined the army when he was seventeen, a year before the age of conscription, to search for his brother. He served for the entirety of the war, and was wounded several times. He fought in the Battle of Berlin, in 1945, and took part in the liberation of Auschwitz earlier that year. When the Nazis captured his native Smolensk in July 1941, the members of his family who refused to evacuate were executed. After the war, he wouldn’t speak about his experiences; he would either cry or make jokes when asked about them. He would say to me, however, that, as his only grandson, it was my duty to care for his medals and his memory. When he died in 2009, I received his medals, but I did not receive his memories.

To fill the void left by my grandfather’s silence, I began to renegotiate a narrative of his time at war by combining machine learning, family photographs, archival material, interviews with Red Army veterans, and forensic field work. “Silent Hero” is not only the result of those efforts but is also an inquiry into how different technologies and methods give shape to memory.

I knew that my grandfather was a war hero, but what does it actually mean to be a hero? In my search for traces of his wartime experiences, I scoured two archives: those of my family and of the state. My family’s archives were underinformed, comprising fewer than two dozen images that mainly showed Grigoriy in a portrait studio, as if he’d spent all his time posing in the flash and smoke of a magnesium charge instead of on the front lines. The state archives, conversely, were overinformed, with epic images of heroism, glory, and honor. Neither set would have helped me arrive at that specific, ineffable scene that would conjure the repressed memories of a relative’s lived experience of war—an image from where a cameracan’t go.

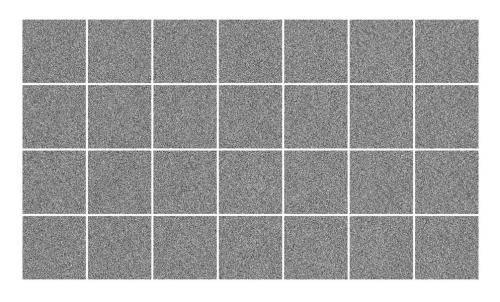

AI became a means for articulating an otherwise subliminal knowledge, filling a gap between archives. To reimagine my grandfather’s war experiences, I collaborated with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), an older form of AI that is fed data, such as real-world images, from which it produces its own synthetic output. A GAN has two components, a forger and a critic. To create realistic, synthetic output, the model goes through an iterative revision process in which the forger produces derivative data in an attempt to trick the critic, which the critic evaluates against its training dataset to distinguish fakes from the original images. This happens again and again, with the forger creating more recognizable images and the critic improving at detection over time.

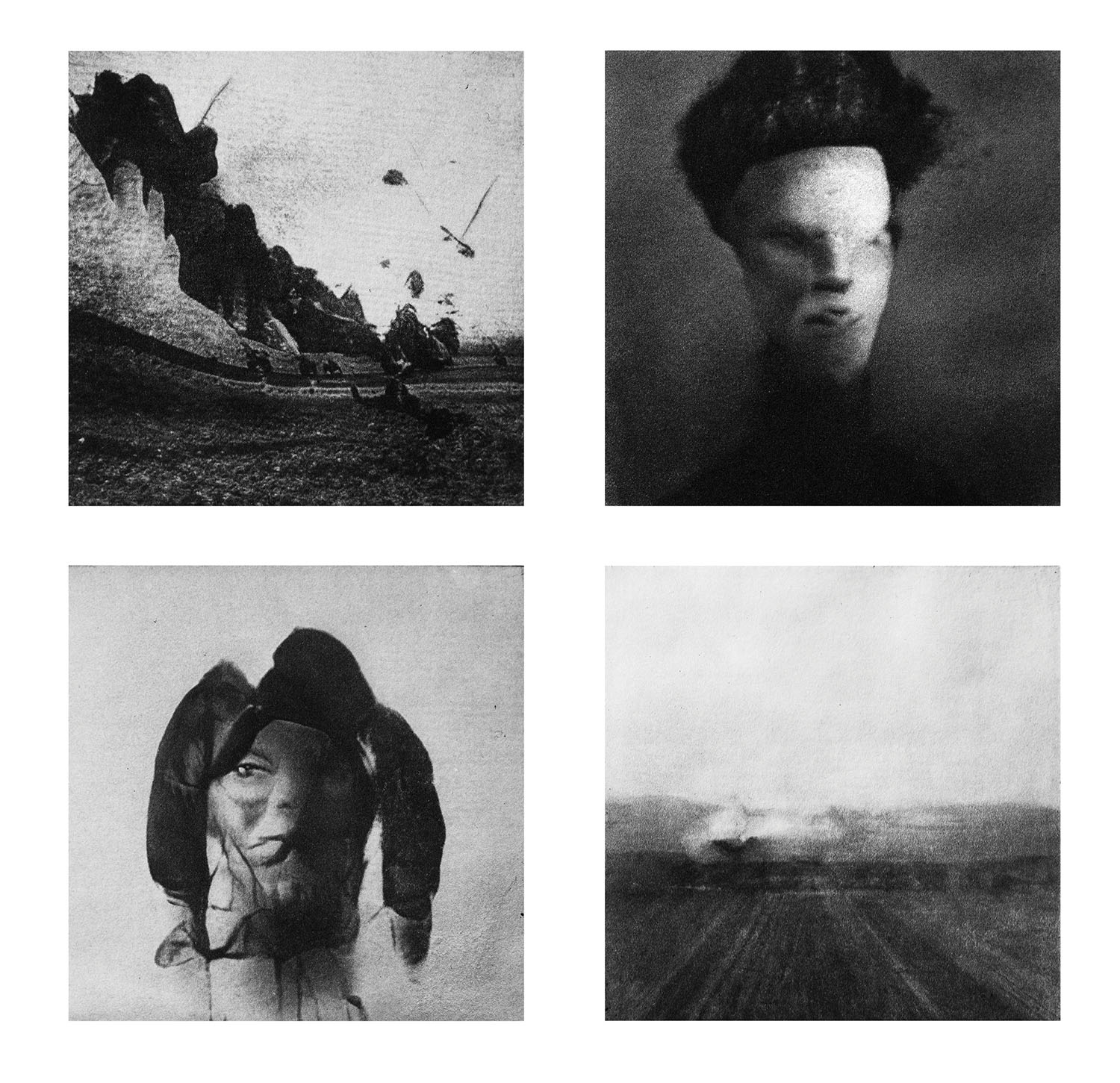

I trained two GAN models—one based on portraits of soldiers posing at a studio or in a field, like those I had found in my family archive, and the other consisting of battlefields in the aftermath of conflict. All told, I used close to 35,000 photographs.1 Once sufficiently trained, each GAN was prompted to produce its own synthetic images. Among the dataset of healthy soldiers posing for their portraits, the figures it produced appeared mauled and nightmarish. The images developed from the battlefield set were abstract but resonant with violence—Rorschachs of war. Throughout the process, the machine spewed out images devoid of any glory or iconic value. AI had created a form of fiction, a fabrication rather than an actual witnessing that nonetheless allowed for new interpretations of war. Unlike photographs, these images aren’t trying to serve as visual testimony for the record. Rather, they express feelings in response to events.

My search for primary-source material also brought me to pamyatnaroda.ru, a database from the Russian Ministry of Defense containing declassified records such as service files, award citations, and casualty and burial records, among others, allowing users to search for their relatives using the digitized documents. While looking for other data, I happened to call up the last known location of Naum Lipkin, my grandfather’s brother. I discovered that he was killed in the Battle of Stalingrad, which lasted from July 1942 to February 1943, but then was subsequently classified as missing in action for nearly eighty years. His decades-long absence was all I had known about him. That historical void defined his existence. To reclaim his presence, I decided to travel to what today is Volgograd, the site of his death and burial provided by the database.

When I arrived, I found myself wrapped in a chilling, silent desolation, the white steppes stretching for miles in every direction. This otherwise featureless expanse was occasionally disrupted by the armature of an electric pylon or a pencil-thin line of birch trees delineating the horizon.

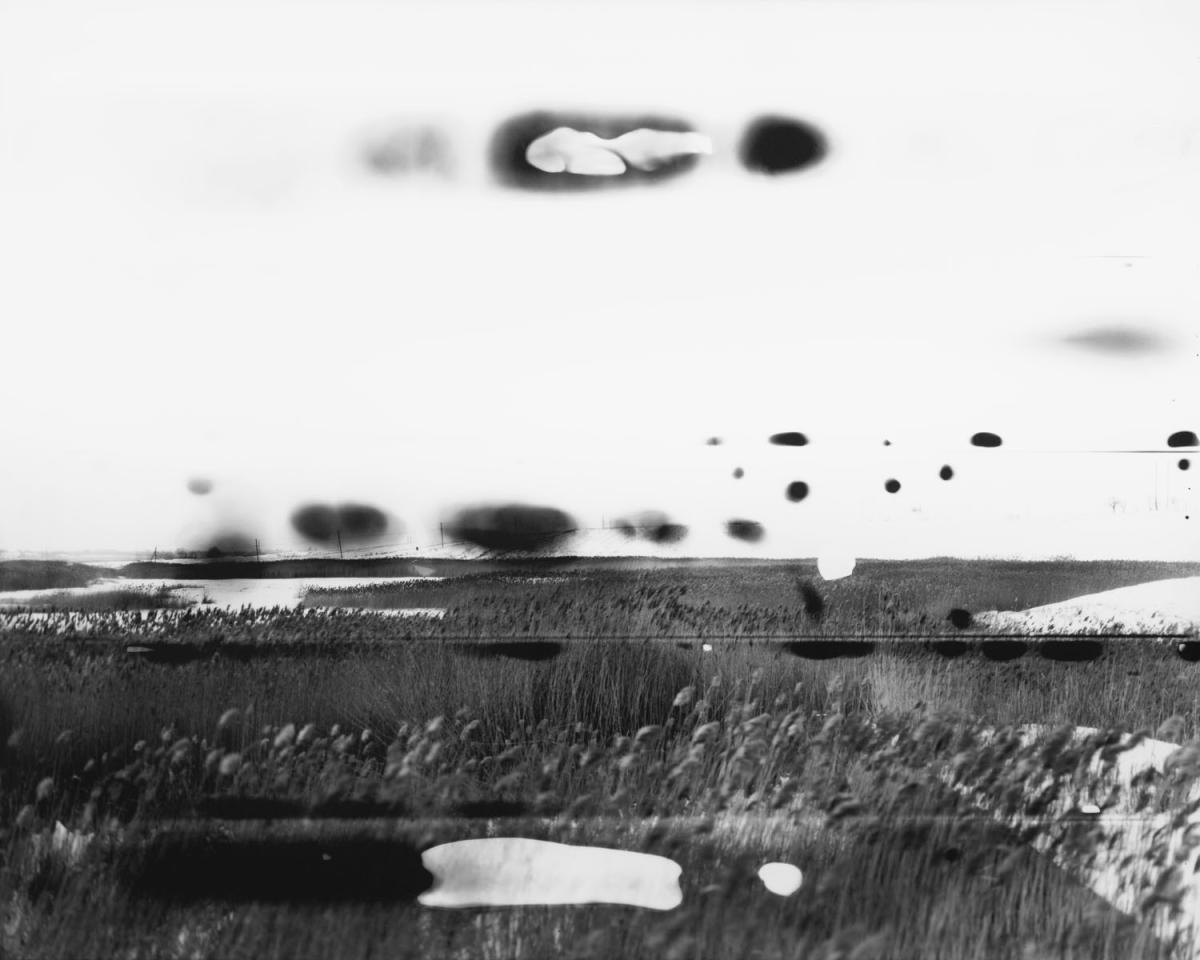

To shoot the landscape, I used an 8x10 technical view camera and orthochromatic film, which is effectively blind to red light and therefore records the landscape in a way fundamentally different from human vision. For me, this photosensitive surface acted as a gestural peeling away of layers of the visible spectrum, not unlike my search for traces of Naum, a way to find, or perhaps summon, specters of the past that could leave an imprint on the emulsion. The images from that trip evoke the voids, the literal and metaphorical wounds, left by war and the abjection of the past.

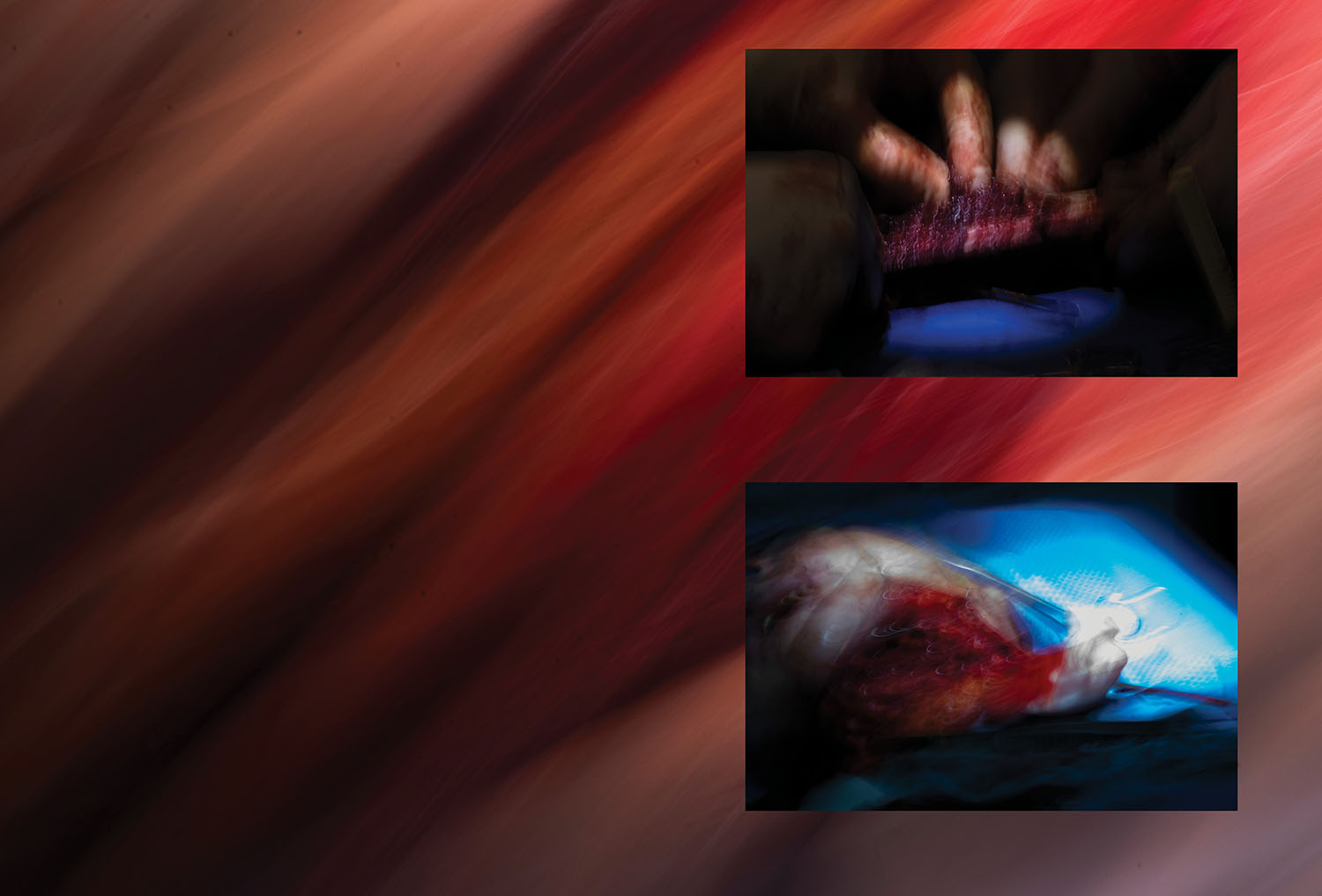

In 1942, my grandfather was severely wounded by shrapnel that pierced his thigh, narrowly missing the bone. As a child, I would drive him crazy begging him to show me the scar. To better understand the unimaginable, in 2023 I traveled to the St. Panteleimon Hospital, in Lviv, Ukraine, as a way to experience an atmosphere similar to what he must have endured as a wounded soldier. I photographed the surgeons at work as casualties of the Russian invasion poured in.

Can a camera measure someone’s perception of horror? One sedated man lay with a swollen, deformed face, his jaw in pieces, teeth wired shut, eyes covered. A team of surgeons and nurses moved in unison. One of the doctors cut into his leg to remove the fibula, a portion of which would provide bone for his new jaw. Another opened the skin around his chin. The room filled with the nauseating stench of burning flesh as body parts were cauterized. I used a digital camera with a bulb-time exposure, holding the shutter open only as long as I could bear to keep my eyes on the traumatic scene. The longer I looked, the longer the exposure, rendering a more abstract image. The shorter my gaze, the shorter the camera exposure, producing a more realistic recorded image.

These photographs, like those from the battlefield, act as cuts—both the literal incisions from the surgery and the visual interruptions in the wartime landscapes. I look at landscapes as wounds, and at wounds as landscapes. What is usually pushed out of view is confronted directly, revealing fragmentation in many forms. Through the visual language of voids, abstract landscapes, and cuts, photographic technologies can alter the distance between historical and contemporary horrors, uncovering the profound impact of war and its collateral damage on memory.

I discovered my grandfather’s medal-decoration orders in his file in the Russian Ministry of Defense archive. The file contains details about one of his medals, an Order of Glory, 3rd class, awarded for an act of bravery in the face of the enemy. The document states that on July 17, 1944, at the age of twenty, “during a counteroffensive in Western Ukraine, Grigoriy killed a sniper and a machine gunner, captured an anti-tank unit of six, and killed four more who resisted, enabling the Red Army to advance and expel the enemy outside the borders of Soviet Union.”

On that same day, my grandmother, Faina, sent a postcard to Grigoriy, made from a photograph she had taken with her girlfriends in a studio. That she and her friends would be posing for a portrait on the same day he was killing enemies in combat speaks to the dissonance of history. Can such a thing be renegotiated? Can technologies bridge imagination and bring together these events, separated in space but proximate in time? Tracing Grigoriy’s footsteps in a Ukraine invaded by its Russian neighbor, standing in a place geographically accurate but temporally dislocated by eight decades: A quantum potential of sorts opens up through the capacities of technology—whether emerging or outdated, whether photography or AI—as I seek to close the loop.

On the back of the postcard, Faina wrote Grigoriy a poem:

The leaves will be reborn again when it gets warm,

The softened earth will sing with streams.

We’ll call for youth’s return

But will not get an answer back

From either fields or groves.

1 One main resource was waralbum.ru, an archive curated by war aficionados, military-history enthusiasts, and independent researchers who work together to identify and contextualize World War II images, recreating chronologies of events based on close analysis of uniforms, equipment, terrain, and other material-culture details.

Starting from gray noise, the generator (“forger”) and discriminator (“critic”) of a GAN advance through early stages of machine learning. After the first one hundred rounds of training, the images produced begin to coalesce into forms that are not yet recognizable, but which already carry visual references to the war archive.

The training data for the AI consisted of 35,000 images collected from public archives of World War II. From this collection, two datasets were used to train two distinct models: Battlefields/Aftermath and War Actors. The former was trained for 1,000 epochs and the latter for 5,000 epochs.

Can a camera measure someone’s perception of horror? Images of facial-reconstruction surgery on a wounded Ukrainian soldier at St. Panteleimon Hospital. Lviv, Ukraine. November 23, 2023.

The images were produced using a digital camera with a bulb-time exposure, holding the shutter open only as long as I could bear to keep my eyes on the traumatic scene. The longer I looked, the longer the exposure, rendering a more abstract image. The shorter my gaze, the shorter the camera exposure, producing a more realistic recorded image.

Top image: 3 seconds

Bottom Image: 10 seconds

After the war, he wouldn’t speak about his experiences; he would either cry or make jokes when asked about them. He would say to me, however, that, as his only grandson, it was my duty to care for his medals and his memory. When he died in 2009, I received his medals, but I did not receive his memories.