Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

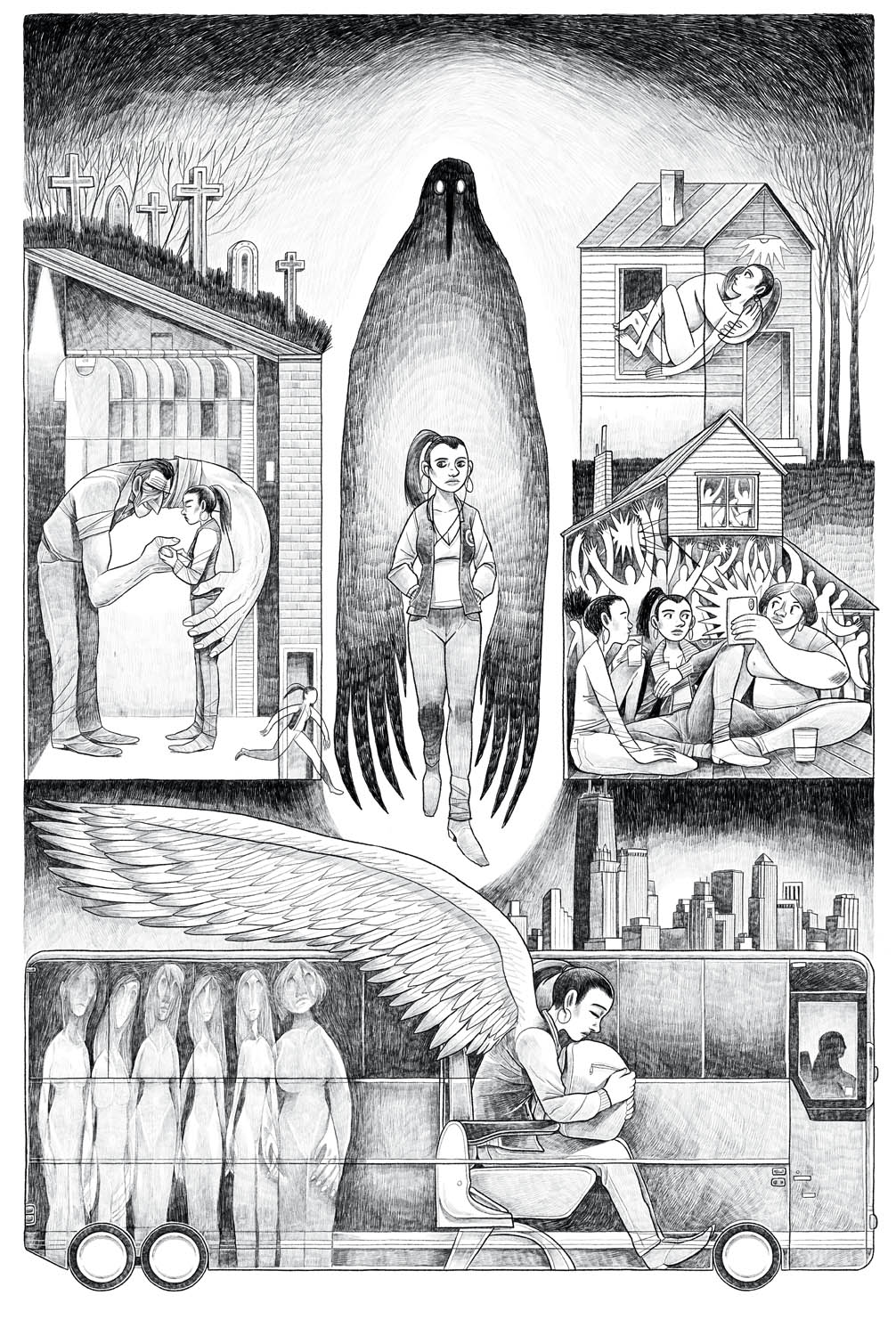

Sergio García Sánchez is a cartoonist and illustrator, and is coauthor, with Nadja Spiegelman, of the graphic novel Lost in NYC: A Subway Adventure (TOON, 2015). His work has been published by the New York Times and others. He teaches at the University of Granada as well as the European School of the...