Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

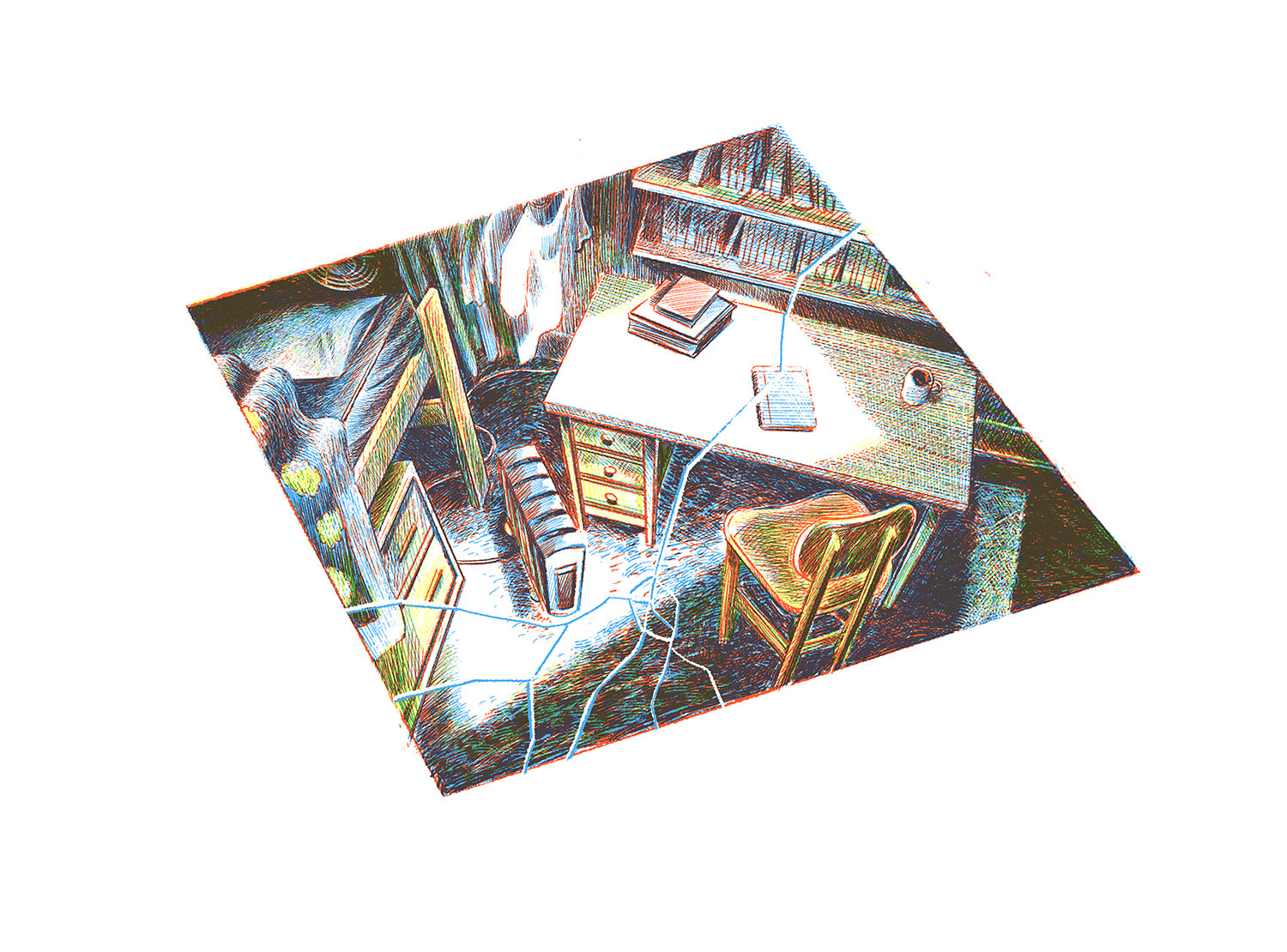

Wesley Allsbrook attended the Rhode Island School of Design. Her work has been recognized by the Art Directors Club, The Society of Publication Designers, the Society of Illustrators, American Illustration, Communication Arts, Sundance Film Festival, Venice Film Festival, Raindance Film Festival, the Television Academy, and the Peabody Awards.