Image

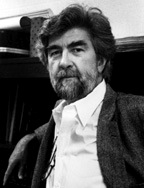

Stanley Plumly’s poetry collections include Now That My Father Lies Down Beside Me: New and Selected Poems 1970–2000 (Ecco, 2000) and Old Heart (Norton, 2009). He has been honored with the Delmore Schwartz Memorial Award, an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, an Ingram-Merrill Foundation Award, and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.