Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

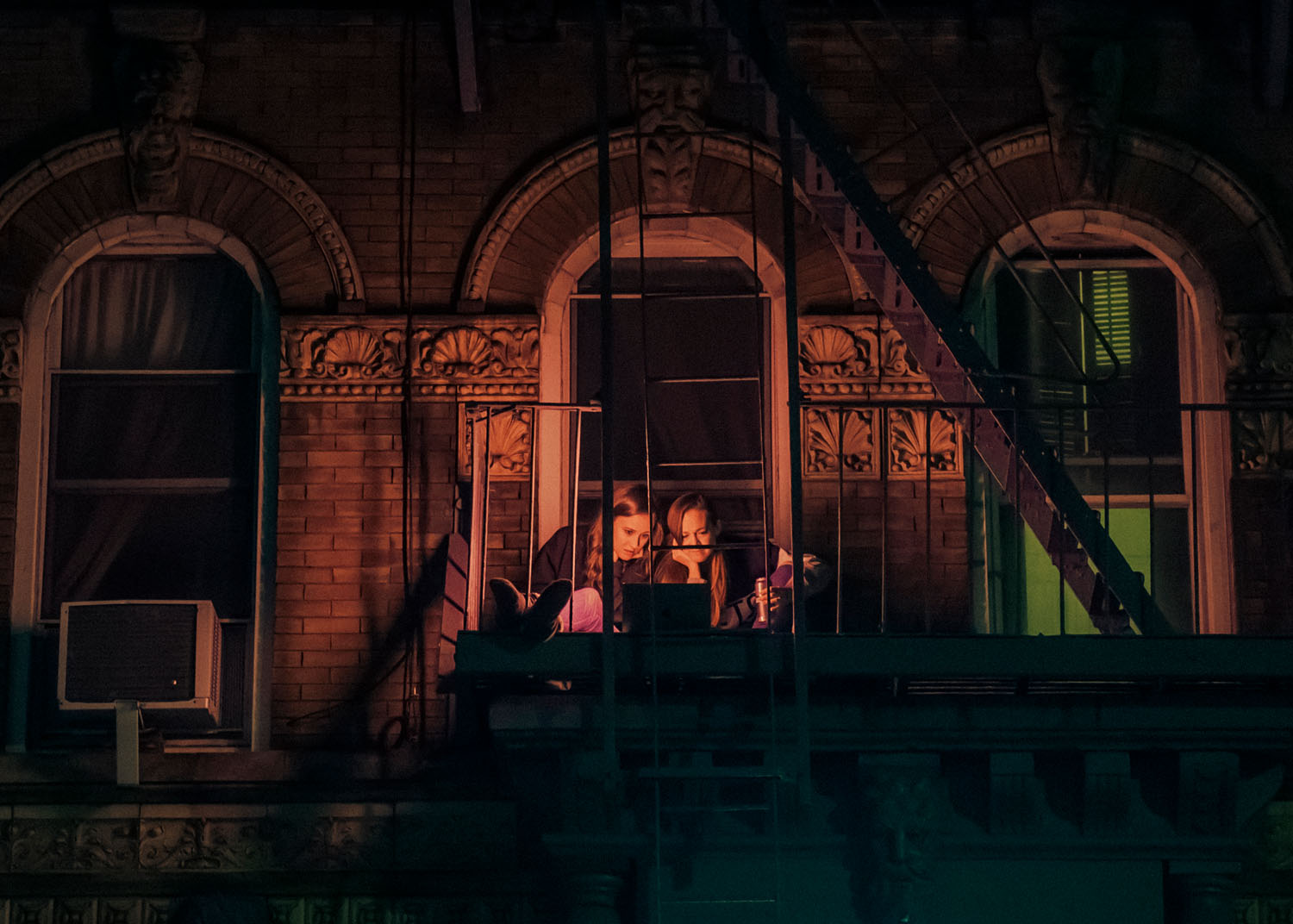

Dina Litovsky received her bachelor’s degree in psychology from New York University and her MFA in photography from NYU’s School of Visual Arts. In 2020, she received the Nannen Prize, Germany’s foremost award for documentary photography. Other awards include the PDN 30, New and Emerging Photographers to Watch; Picture of...