Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

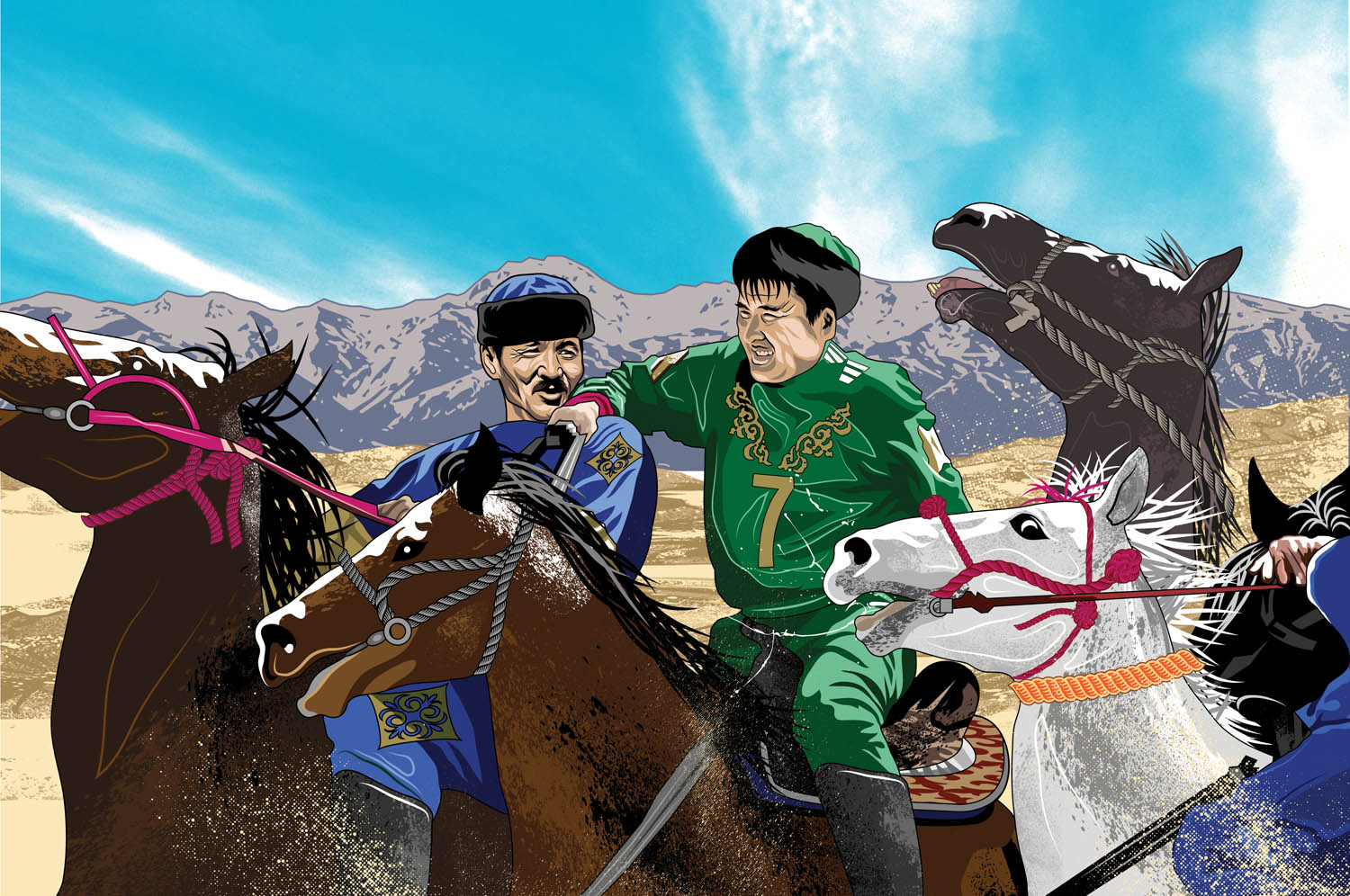

Guy Stauber has recently exhibited work at Hero Complex Gallery in L.A & Comic Con in New York. His clients include Sports Illustrated, DC, Marvel, Lucasfilm, and Disney, among others.