Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

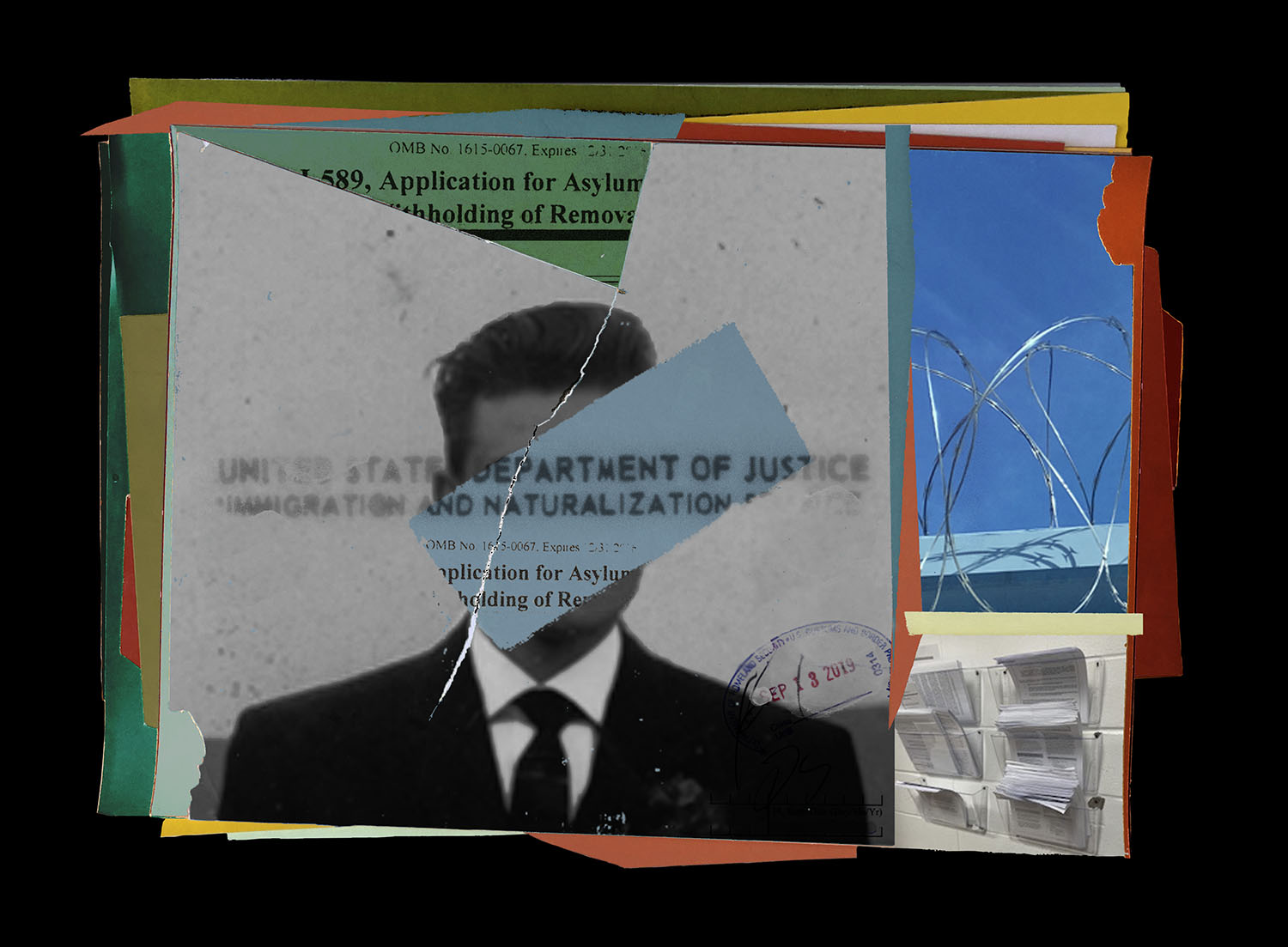

Jen Renninger is an editorial illustrator who works in collage and painting. Her illustrations have been featured in the Washington Post, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Harper’s, and Chronicle Books.