A Language for Reinvention

The first time I escaped a language was in spring 1983. I was nine years old and living with my family in Barcelona, the city where I was born. My parents had just been informed that all my classes the following school year would be taught in Catalan, a language General Francisco Franco, who ruled Spain for more than thirty years after winning the Spanish Civil War, had tried to erase from cultural memory. Franco banned the public use of regional languages like Catalan, Basque, and Galician, and declared Spanish the only official language as part of his drive for a nationalist agenda under the motto Una, grande, y libre—“One, Great, and Free.” The slogan was a callback to the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castille and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, who had marked a period of national consolidation after the reconquest of Granada and the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from Spain.

With Franco’s death and the transition to democracy, the Spanish Constitution of 1978 set up the basis for a new institutional and territorial organization of the Spanish state that provided more administrative autonomy to its regions. Reestablishing Catalan as an official language of Cataluña, where Barcelona is located, was a logical consequence of this shift, but it was unacceptable to my dad, the son of a colonel who had fought with Franco. Such was the offense that by summer we had moved to the suburbs of Madrid, the epicenter of Castilian Spanish. It was then, very early in life, that I learned how language is an elemental part of cultural identity—so much so that a dictator would do everything possible to exterminate it with the purpose of enforcing his power, never mind that a man would upend his family to avoid it.

Even though Catalan was banned from public use during Franco’s dictatorship, many families continued to speak it at home, a fact the regime didn’t seem to care about if it happened behind closed doors. As a queer man, I can’t avoid drawing a parallel between the policing of languages and sexual behaviors as ways to suppress identity. I remember clearly when I came out to my father in my early twenties, shortly after having moved to New York. “It’s okay to be gay as long as no one from my circle finds out,” my dad said. So, I could be gay, and Catalans could speak their language if we did it in private. By then Franco had been dead for more than two decades, but not even fourteen consecutive years of a progressive Socialist Party mandate would change that generation’s ideology, nor their intention to perpetuate their power.

The second time I escaped a language was conscious and planned. In the summer of 1997, right after college, I left the suburbs of Madrid for New York City to learn English and the language of my body. This was in the aftermath of the AIDS epidemic, and my obsessive fear of the virus didn’t stop me from getting lost in the back of dingy bars, dark rooms, and in apartments all over the East Village. The Cock was then on Avenue A, the Beige parties on Tuesdays at B Bar were still unbridled fun (before the early 2000s turned them into the dullest see-and-be-seen parties of the week), and the Wonder Bar was so truly full of wonders that I met my first boyfriend there. The world was analog and still mostly offline.

Because leaving my birth country happened in Spanish and coming to terms with my sexuality happened in English (albeit rudimentary), I cannot decouple my coming out from establishing myself in America. English was a language whose words were new and shiny and free, detached from shame. It is hard to believe that nearly thirty years after I left Spain and almost ceased to speak in my mother tongue, the Spanish pronunciation of the word homosexual, which is spelled the same way in both languages, haunts me with the familiar feeling of inadequacy that kept me up at night as a kid, trying to bury under the covers the questions my body insisted on asking.

I often wonder what would have happened if instead of moving to New York, I had moved to Paris. If, instead of English, my adoptive language had been French. Geographically speaking, and given my childhood obsession with Tintin, the Belgian twink reporter whose best human friend is an old sailor (and a leather daddy, as I would later surmise), moving to Belgium or France would have been more logical. But learning to speak and write in another language whose origin is also Latin might not have been enough. Said a different way: The French language is possibly too close to Spanish, too close to home. I also wonder whether actual distance, especially before the internet altered our collective perception of space, played a more crucial role than I had first thought. I needed to have more than just a few hundred miles between my old self and my new self; I needed a whole ocean. Freedom for me speaks a language other than my mother tongue.

I visit Spain a few times a year, which means that in my twenty-eight years living in New York, I have crossed the Atlantic nearly a hundred times. Up in the air, unable to sleep, I question my feelings toward Spain, a country I feel obliged to connect with. The truth is that, unlike many immigrants, I do not miss my homeland. I do not miss the food, the music, the weather, the so-called “quality of life.” But that is not to say that I am not envious of those who speak about their countries of origin with longing.

My sentiments toward my birth country seem always to be changing. Now, after almost three decades abroad, I have become more accepting of the fact that my foreignness is fluid. The last time I landed at the Madrid airport, as I stood on the autowalk gliding past others rushing back and forth, I wondered, with two different passports in hand, when exactly it had happened: the moment I went from being a foreigner in America to being a foreigner in Spain. And whether it matters. After all, to grow up queer is to grow up a foreigner.

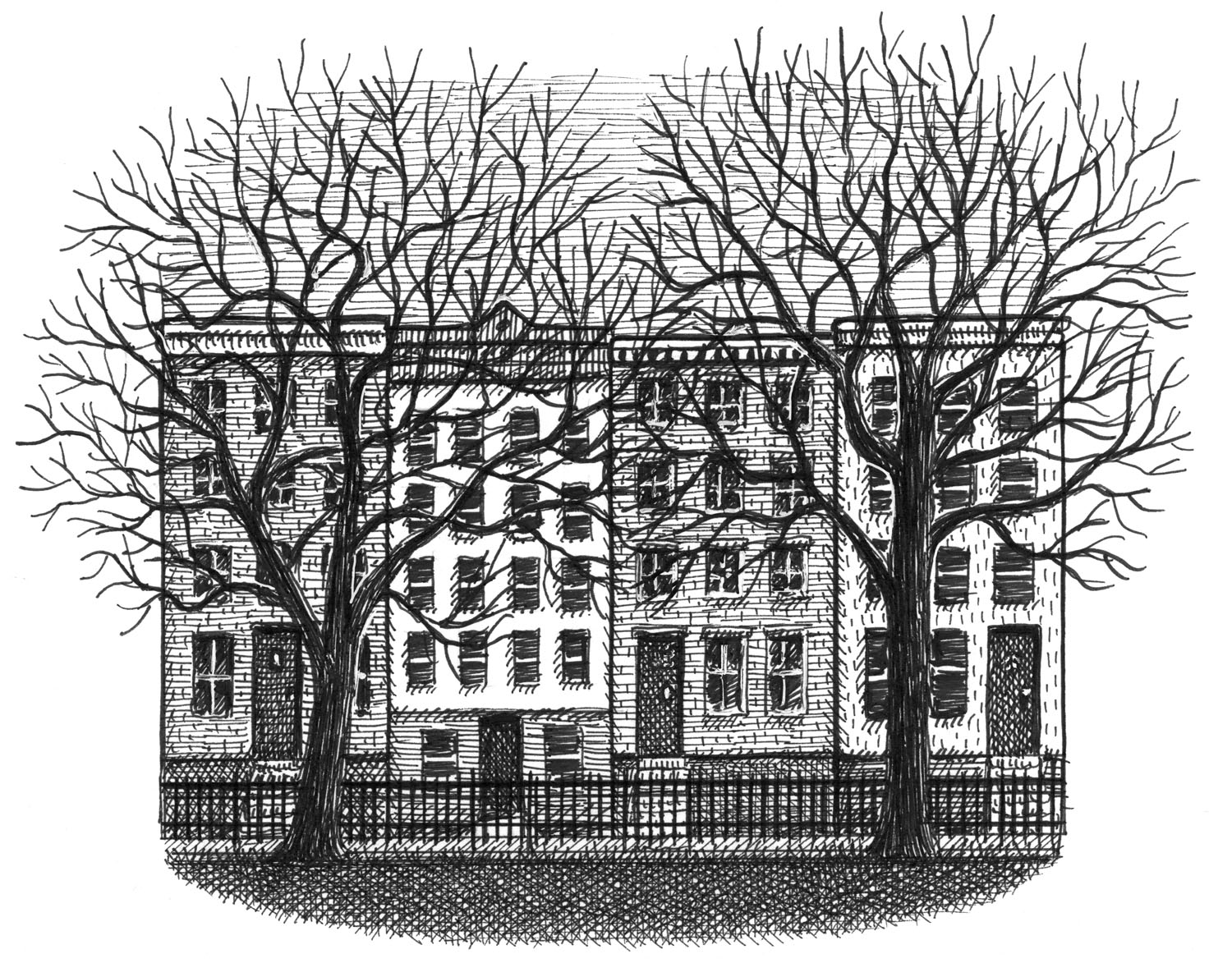

It is perhaps not a coincidence that I have lived most of my life in New York City, in which a staggering 38 percent of the population is foreign-born, in a city bathed by the same ocean as the Cadiz coast, where I learned to swim as a child. I am beginning to accept that I exist more wholly in between countries, in between places. Transitional spaces like airports, bridges, an empty lobby, or a lonely country road have always comforted me. In this pleasing nostalgia, triggered by anonymity and a feeling of aloneness as I travel across them on my way to a destination, the possibilities to reimagine who I am and who I could become manifest themselves naturally. It shouldn’t be a surprise, then, that I feel most at home in the liminal spaces. Is there a better metaphor to express liminality than an empty sheet of paper on which characters will eventually emerge and react to an inciting incident, navigate through different plot points and experience a climax?

Memories of my adolescence, when I fabricated a more masculine version of myself, echo in my mind. Even now, listening to myself talk to my childhood friends, I still notice in my voice an inherent performative masculinity that I detest, a masculinity only present in Spanish. It reminds me of the years when I didn’t have the freedom to be who I truly was. My conservative upbringing and my dad’s unreasonable request that I render myself invisible forced me to leave the place that was supposed to be home, transforming my relationship to my mother tongue and my homeland. But, in searching for that new space in which I could safely be me, I found a new language where I finally feel at home.

Landis Blair is the author and illustrator of Vers le Sud (Les Éditions Martin de Halleux, 2023), The Night Tent (Holiday House, 2023), and The Envious Siblings: and Other Morbid Nursery Rhymes (Norton, 2019). He is also the illustrator of the New York Times bestseller From Here to Eternity (Norton...