In the Hallowed Place Where There’s Only Darkness

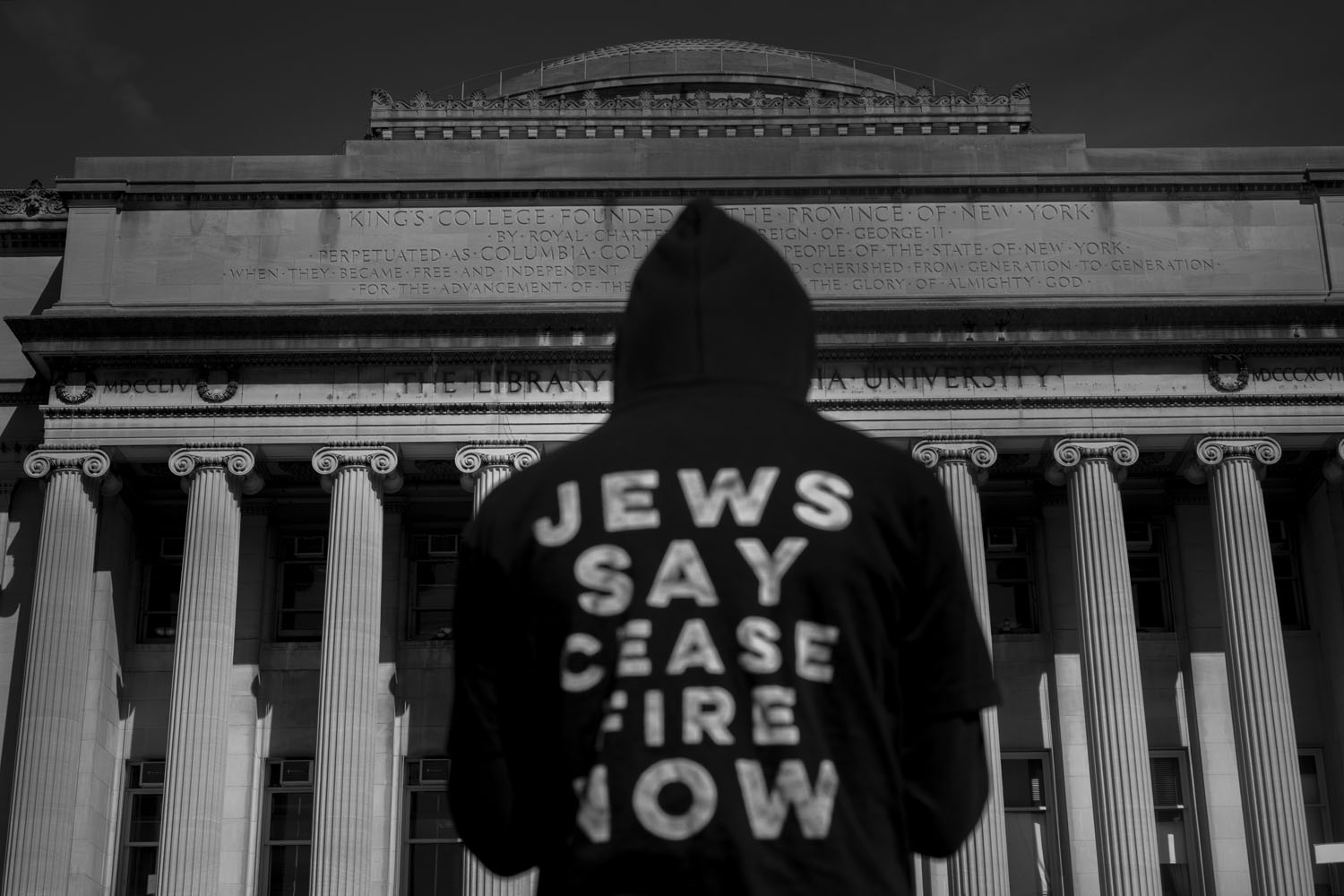

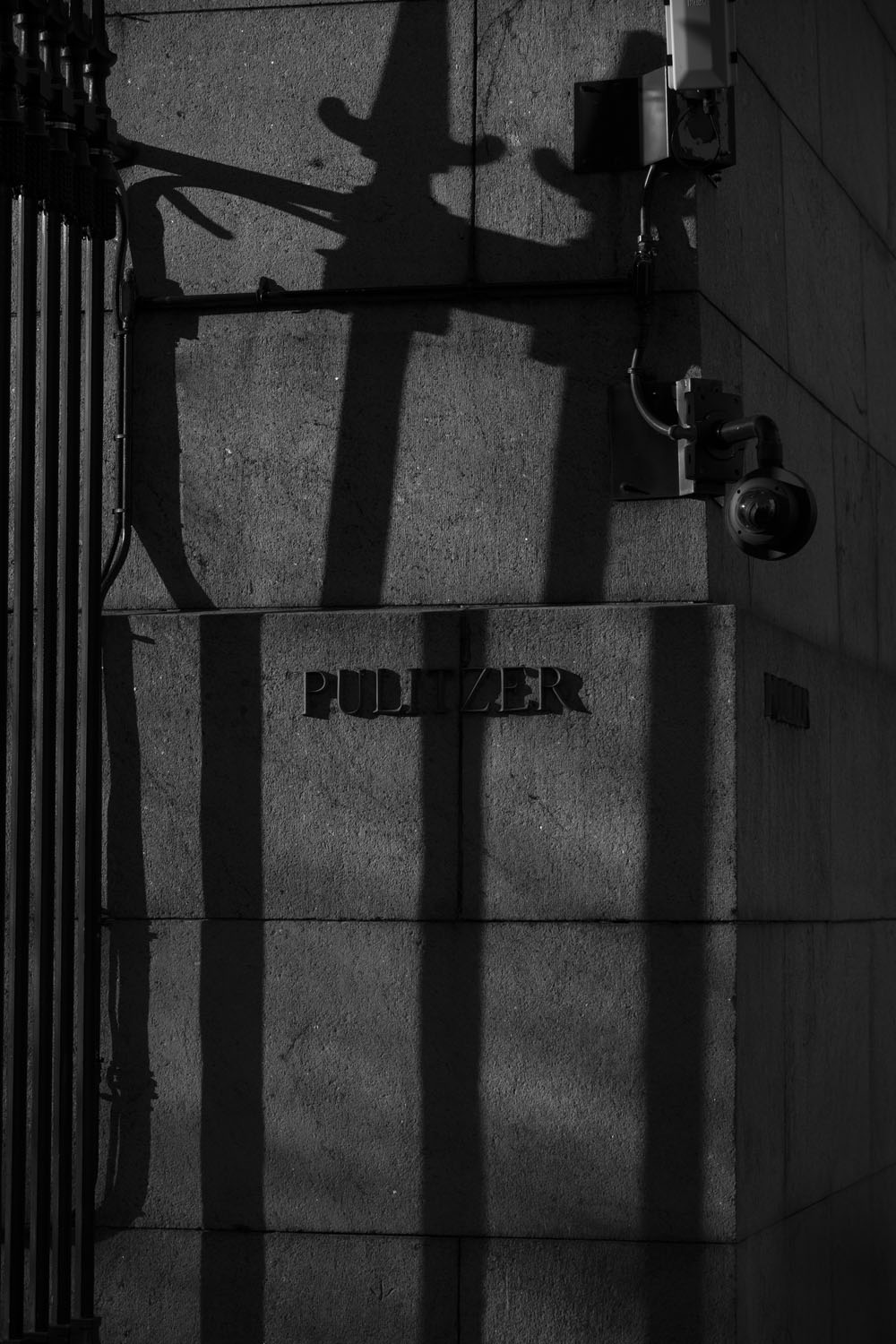

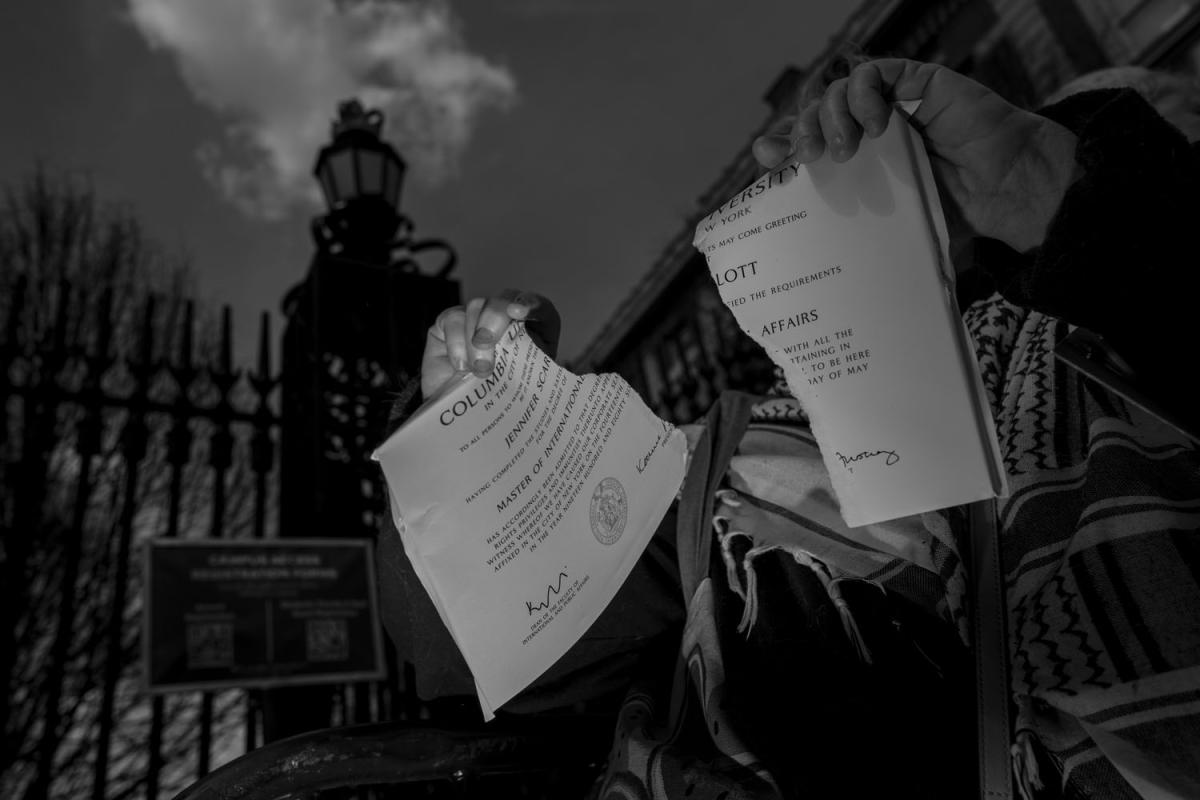

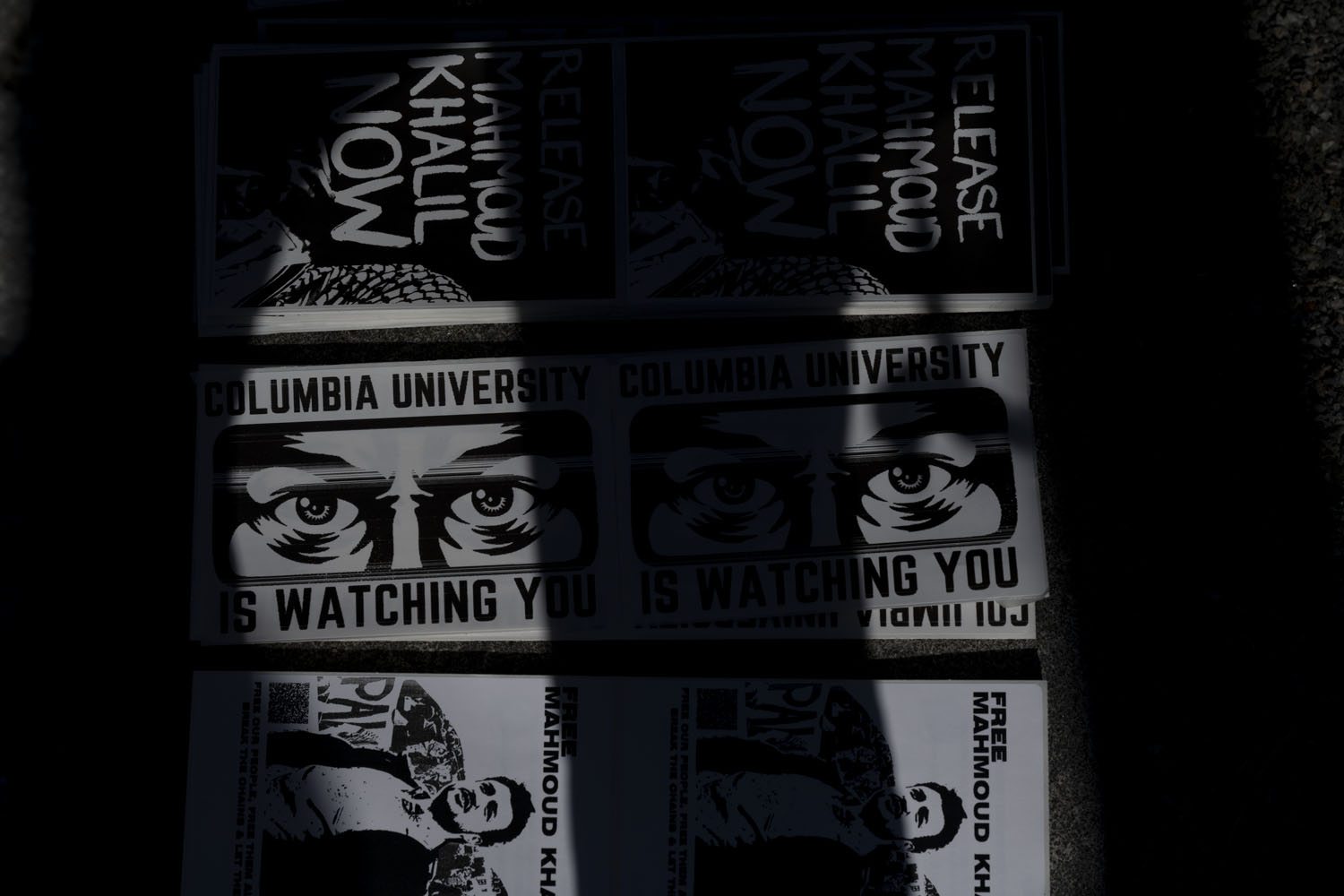

For more than fifty years, I have been studying and writing about political repression and higher education, with a special emphasis on McCarthyism, long considered by historians to be the most serious assault on academic freedom since the emergence of the modern university. But, as Nina Berman’s photographs of Columbia University show, what has been happening to the American academy these days is incommensurably worse. Berman, who teaches in the journalism school at Columbia, has spent decades documenting protests and the like, and naturally did so again in 2024, when pro-Palestinian demonstrations unfolded on the campus where she teaches. In the year since, she has continued to photograph with an almost diaristic discipline, and has amassed a visual narrative of Columbia’s painful transformation. In these haunting images of a locked-down campus bristling with surveillance cameras and security guards, we see autocracy revealed in the form of a restive yet silent space under control. Because Columbia’s leaders have capitulated to the Trump administration, a once-proud citadel of higher learning and independent thought is losing its credibility.

Columbia’s situation is neither unique nor unprecedented. The nation’s colleges and universities have almost always given in to outside political pressures. They did during the 1950s and they do so today. But they have never faced such an existential threat. Despite the academy’s central role within American society, the forces arrayed against it are both more powerful and more focused than ever before. Meanwhile, the structural and ideological transformation that occurred within higher education over the past five decades has rendered it increasingly vulnerable to its enemies.

In the fifties, college administrators fired and blacklisted more than one hundred professors, most of them tenured, because of their supposed connection with communism. But they were never questioned about their teaching and research; they lost their jobs only because of their extracurricular political activities and their resistance to the anticommunist inquisition. McCarthyism did not single out the university; its protagonists selected whatever targets would bring them attention. Their ostensible goal was to eliminate the alleged threat to national security posed by the Communist Party. The inquisitors justified their operations by invoking a demonized portrayal of party members as robots under Moscow’s control who sought to betray their country to the Soviet Union. There was enough plausibility to that scenario to allow McCarthyism to dominate domestic politics for nearly a decade, especially after the Republican Party adopted the anticommunist crusade as its main weapon against the Truman administration in the late 1940s.

The Cold War red scare did not rely heavily on violence or criminal prosecutions; its sanctions were mainly economic. It implemented a two-stage procedure that first identified the supposed subversives, and then punished them. That first stage of exposure was usually handled by an official body like the FBI or a congressional investigating committee. In the second stage, the victims’ employers, including the colleges, did the dirty work. The faculty members who tangled with the witch hunt did not, as was assumed, engage in subversive activities, indoctrinate their students, or skew their research. But they weren’t “innocent liberals” either. Most had once been in or near the Communist Party and would have been willing to talk about it, though they wouldn’t agree to name names. The administrators who fired them knew that.

Still, the mere whiff of communism was so lethal that every institution that employed these tainted professors invariably investigated and then usually dismissed them. There was essentially no opposition. Faculties and students kept quiet or supported the purges. In the spring of 1953, just as the main congressional investigators were about to descend on the nation’s campuses, the Association of American Universities, whose members consisted of the presidents of the thirty-seven top research universities in the US and Canada, issued a widely circulated statement claiming that prospective witnesses had “a duty as professors” to cooperate with the committees. Even the ACLU and the American Association of University Professors, a body that protects academic freedom, remained silent.

No surprise, then, that what Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas called “the black silence of fear” enveloped the academy. Professors censored themselves, pruned their syllabi, and no longer taught courses about sensitive subjects. They even changed the words they used in their classes. The eminent literary critic Leo Marx later told me he stopped mentioning “capitalism” in his lectures and talked about “industrialism” instead. And, of course, both faculty members and students abstained from left-wing politics.

The political repression of the 1950s seems like a gentle breeze compared to the category 5 hurricane we face today. While McCarthyism targeted individual professors only for their politics, the MAGA regime has its sights set on all of higher education. Pushed by an authoritarian White House that selected Columbia as its guinea pig, the current offensive interferes with just about everything that happens on the nation’s campuses: biomedical research, courses about controversial issues such as race and gender, syllabi, student discipline, DEI programs, admissions policies, athletics, library books, international students and teachers, accreditation, academic programs, endowments, whole departments like Gender and Ethnic Studies, and even an entire institution: Florida’s New College.

The Trump administration’s assault on the university stems in large part from the carefully crafted efforts of an ultraconservative network of opportunistic politicians, libertarian activists, reactionary billionaires, and Christian nationalists who, in response to the social movements of the 1960s, sought to put an end to the ivory tower’s adherence to democratic learning and free expression. They hoped to destroy the university’s influence within American society. Over the past fifty years, hundreds of millions of dollars have flowed into right-wing think tanks, publications, academic programs, and other organizations, creating the so-called culture wars that have eroded faith in academic expertise in addition to instilling the widespread belief that higher education is dominated by elitist radicals.

Pro-Palestinian heads have been rolling in academe ever since October 7, 2023. Now, the academy’s leaders, blindsided by the breadth and brutality of the Trump administration’s attack on their institutions, if they are not already endorsing its assumptions, concede much of the battlefield, legitimating the government’s assault on their autonomy—as they did during the Cold War red scare. Only this time, because of the ongoing culture wars and neoliberal restructuring of the academy that began in the 1970s—as well as the failure of academic leaders to fight for the value of liberal higher education—their institutions may not bounce back.

McCarthyism, despite its inroads against academic freedom, coincided with the start of what came to be known as the “Golden Age” of higher education. Colleges and universities enjoyed considerable public support as they expanded exponentially, while state legislatures and the federal government practically threw money at them. That generosity, however, came to an abrupt end in the 1970s amid a worldwide economic upheaval, in addition to a right-wing backlash against the student unrest of the 1960s. Suddenly the once-prestigious and well-funded system of American higher education encountered austerity. State politicians cut budgets, and feder-

al funding became harder to get. Influenced by the political elites’ adoption of a neoliberal economic regime that prioritized the market and sought to shrink the size of the state, academic administrators responded to their newly straitened situation by implementing purported “reforms” that restructured their institutions to accord with the corporate business model they believed would protect their bottom lines.

As a result, their schools’ mission became growth, not the production and dissemination of knowledge for the betterment of society. As they sloughed off such supposedly inefficient accoutrements of the traditional academy as faculty governance and the preparation of undergraduates for something more than a job, colleges and universities emulated the business community’s highly competitive top-down practices. They centralized their administrations and took on so many new functions to meet the demands of the market and federal government that sometimes administrators came to outnumber faculties. They also paid more attention to attracting tuition-paying students and courting wealthy donors who demanded more control over the schools, while directing their millions to football stadiums and name-brand architects’ flashy buildings rather than instructional costs and the maintenance of older classrooms and offices.

As administrators cut costs, they usually did so without input from the faculty—until, that is, its members were told to compile lists of which professors and departments would get the ax. These cutbacks have become increasingly common since the COVID crisis and directly impact the academy’s core educational operations. A particularly deleterious practice is the university’s increasing reliance on non-tenure-track contingent faculty members. These poorly paid part-time and temporary workers now make up over 70 percent of the nation’s faculties. They are as well-credentialed, experienced, and competent as their more economically secure colleagues, but, unless they are covered by strong union contracts, they are second-class citizens—often without benefits, professional support, or academic freedom. Many are hired at the last minute and can be let go at any time, for any reason, or for no reason at all. And they have little if any voice in their institutions’ faculty governance—as if full-time tenured professors still have a say over such decisions on their campuses.

All these changes have undermined the willingness and ability of the highly polarized academic community to fight the authoritarian campaign against the American mind. In response to the wave of pro-Palestinian demonstrations, campuses have become battlegrounds, though few may be as militarized as that of Columbia, which has augmented its security apparatus with “special officers” empowered with the ability to arrest students, and has multiplied its system of gates, cameras, and ID cards such that it sends a forbidding message to the surrounding community—and an even more hostile one to its students and teachers.

“The thing that really chills me and other faculty is that Columbia hasn’t defended itself,” Berman says. “They haven’t defended their students, and they haven’t defended their faculty. We see no accountability for those at the top. Instead, what you see is micromanaging and going after students, spending who knows how much on a security infrastructure that is completely opaque.”

And, yet…

There is hope. McCarthyism encountered no serious opposition. But today, students and professors are mobilizing on Morningside Heights against Columbia’s crackdown on dissent, failure to protect its students from ICE, and other forms of collaboration with the Trump regime. Similar resistance is springing up throughout academe as students and faculty members seek coalitions with like-minded groups both on and off their campuses. Their activities are making a difference. Even the president of Harvard, despite his ousting the leaders of its Center for Middle Eastern Studies and conceding more than he should have to the hypocritical campaign equating criticism of Israel with antisemitism, refused to capitulate entirely. Other institutions, including the Association of American Universities, are also speaking out. A broader resistance movement may be in sight.

It may take years to create enough pressure to end the war on higher education, but it can be done. As the historian Carolyn Eisenberg’s recent prize-winning book about the Vietnam War, Fire and Rain, reveals, the antiwar movement that began on American campuses in 1965 was a key factor in forcing President Nixon to bring it to an end. Solidarity is essential. Only a united effort for a common cause will make it possible to save a free, just, and inclusive system of higher education—and the democratic polity that needs it.

Nina Berman is a documentary photographer, filmmaker, journalist, and professor at Columbia University. She has written three books: Purple Hearts: Back from Iraq (Trolley Books, 2004); Homeland (Trolley Books, 2008); and An autobiography of Miss Wish (Kehrer Vlag, 2017). She is a 2025 Guggenheim fellow in photography and lives in...