In the Silences Between Caution and Hope

This project was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. Reporting was conducted between December 2024 and March 2025.

It’s easy to be cynical about Syria. Westerners have become largely inured to the bad news coming out of the country, where, under the brutal Baathist regimes of Bashar al-Assad and his father, Hafez, before him, tragedy had come to seem like a refrain. Hundreds of thousands of people killed or disappeared; barrel bombs and chemical attacks ravaged the country. Over time, the news was enough to exhaust most people’s capacity for empathy.

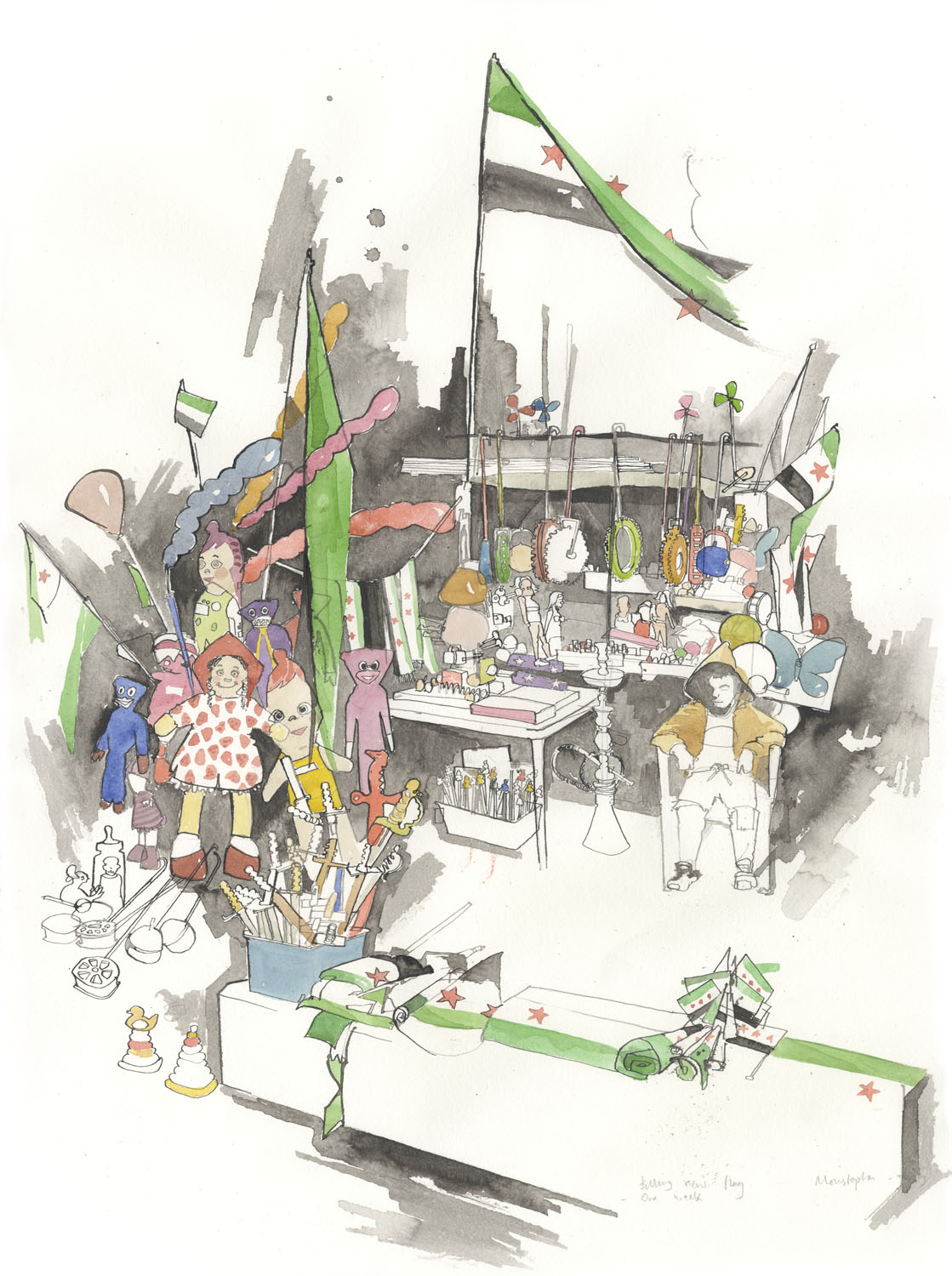

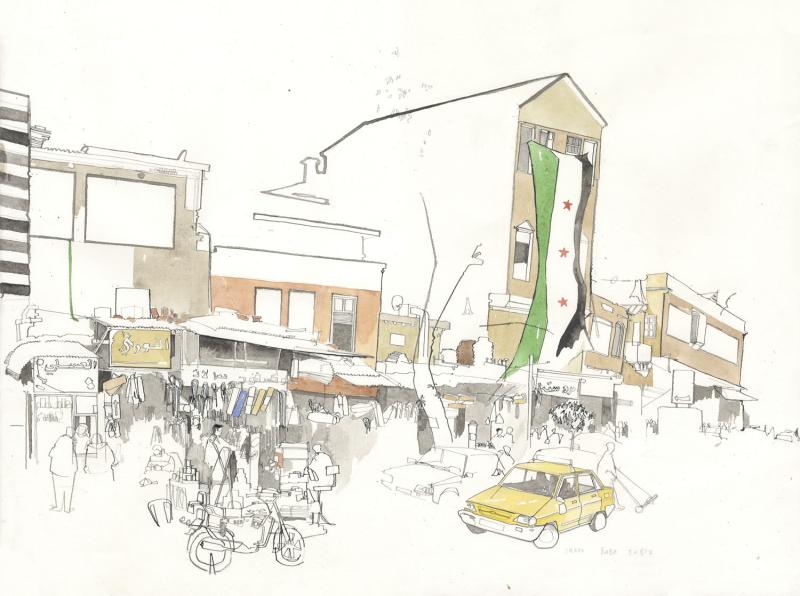

Which is what made the good news, however brief, such a jolting headline. In the early hours of December 8, 2024, after ten days of fighting with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, a rebel group led by Ahmed al-Sharaa (known by his nom de guerre, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani), the Assad regime collapsed. Fifty years of family rule evaporated overnight. Bashar al-Assad had fled to Moscow for asylum. Disbelief turned into euphoria; people flooded the public squares. Jubilation passed from one person to the next as “Free Syria” was shouted in the streets.

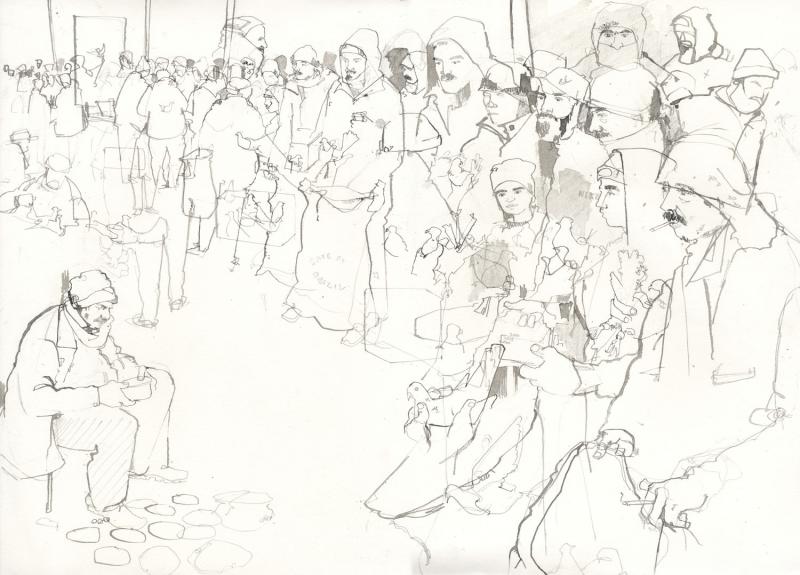

I returned to Syria on December 11—my first trip back to the country since 2013, when I was reporting on the Free Syrian Army in the small, war-stricken town of Azaz. During that earlier trip, I felt such affinity with the civilians I’d met that, upon returning to London, friends and I founded an organization called Action Syria, which raised more than $10 million for humanitarian work in provinces and neighborhoods the regime refused to help. In 2013, working in Azaz, I drew an incongruous scene of children playing on a burned-out government tank, which came to mind this time as I watched hundreds of people celebrating on and around a tank parked in Umayyad Square in Damascus. Young men fired Kalashnikovs into the air, people handed out dates. Others put chocolate bars in my shirt pocket. Smiling seemed infectious.

On the streets of Damascus, Aleppo, and Homs I discovered a narrative of cautious hope. As Hadeel Ali, a twenty-six-year-old dentist from Damascus, put it to me, “We are so old that we have white hair on our heads waiting for this moment.” She was paraphrasing a famous statement made by a Tunisian activist celebrating the fall of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, in 2011. “I feel the same way,” she said. “I am shaking with joy. I feel a mourning for everyone who died for no reason, but we are finally free.”

Since those first few weeks, international flights have returned to Damascus, with visas on arrival for some nationalities, and Beethoven has been heard in the Opera House. Murals of Hafez and Bashar al-Assad’s faces have been painted over. But conditions haven’t changed much for most Syrians, 90 percent of whom live below the poverty line of just over $2 a day.

Six months is not long enough to tackle the challenges of a destitute economy, deliver accountability, or mend utilities. However, there are reasons to be optimistic, including the cessation of sanctions by the US, and the fact that Qatar has agreed to pay state salaries for three months, with Saudi Arabia joining in to offer additional financial support. Refugee camps that had been full for more than a decade have all but emptied out, and 680,000 refugees have returned home from abroad. What’s more, civil society—the bedrock of the Syrian humanitarian response—is flourishing across the country.

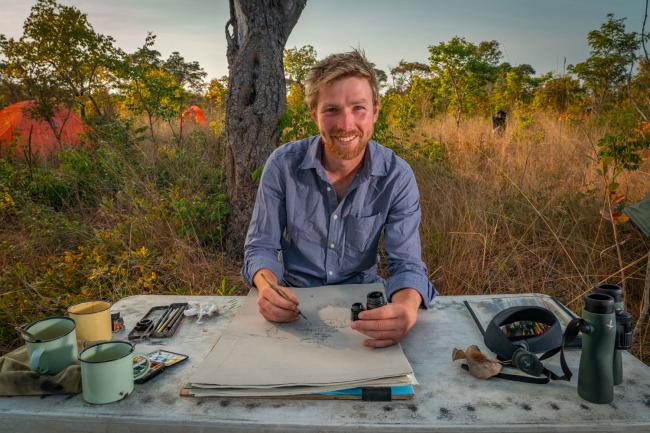

These interviews began as portraits. But as I drew, my subjects talked. They shared memories that carried unimaginable weight, traumatic experiences that had been practically unutterable for a generation. Many had given up the notion that the truth would ever be told at all. And as we talked, in each conversation, there was an undercurrent of tension around a simple question: Could a free Syria really last?

On March 6, I visited Latakia, interviewing Alawites about an incident in the northern part of the city, where several Alawites had been killed by the new government’s general security forces. There was plenty of suspicion that the killings were driven by sectarian tension, something that had been ongoing in small conflicts here and there around the country.

Just as we finished our lunchtime meeting, a Russian jet flew overhead. Mobile phones all around us started ringing with calls from family and friends. Panic set in: Across Syria’s coastal region, Sunni militia forces, comprising both state and non-state actors, were slaughtering Alawite civilians amid their clashes with armed pro-Assad loyalists. The massacre would last for several days—a death toll that would surpass a thousand people, half of whom were civilian men, women, and children. The reality of sectarian revenge that many had feared would undermine the new government’s legitimacy had finally been unleashed.

In trying to tell the stories of the Alawites, members of a sect of Shiite Islam that makes up 10 percent of the Syrian population, and whose numbers include the Assad family, I was reminded time and again of just how complicated it is to differentiate those who were accomplices in a dictator’s violence from those who weren’t. Many Alawites are worried that the new government will either ignore vigilante reprisals against them or, worse, target them for their perceived complicity in the former regime’s crimes. Either way, in a country whose future remains unpredictable, the fate of Alawites is even more precarious.

One story in particular haunted me. Nour—not her real name—is an Alawite woman who lived just south of Latakia. On March 7, armed forces descended on her neighborhood and began looting shops and homes. “They only targeted the areas where Alawites lived,” she told me. “While hiding inside our home, we heard a lot of gunfire, so I peeked out a window and saw hundreds of people being attacked.”

The next day, Nour’s father and uncle headed out to go stay with family who lived elsewhere. At a security checkpoint, they were told to step out of their car, and her father was asked if he was Alawite or Sunni. “I am a Muslim,” he told them, but they knew the answer. They sent her uncle off, and shortly thereafter shot Nour’s father five times, leaving him for dead in the street.

A passerby saw him and, realizing that he was still alive, drove him to the hospital. When they arrived, he told them he was Sunni, for fear that he might not receive care otherwise. He died there the next day.

“Thanks be to God in all things—it was preordained by God, and whatever he wills is done. At least we were able to take my father’s body from the hospital and bury him,” Nour told me. “Not everyone was so lucky.”

It was my intention to reach beyond the tyranny of the Assad dynasty by telling the stories of those who had survived it. I felt that drawing what I saw could better explain what they felt—a rare chance for the tyrannized to tell their truth.

It wasn’t easy. Some people were terrified of what might happen to them if they talked. A Yazidi man who had lost twenty-three members of his family to ISIS broke down in tears when he tried to recount his story, his fear so palpable that we ended the interview. An Alawite who worked in public service for the Assad government, who fled to Beirut and then Jakarta, Indonesia, asked that his name and job title not be published in case his parents were attacked in Damascus.

All too often during the fifty or so interviews I conducted, some of which are collected here, I was met with the same answer when I asked about people’s plans, or their hopes for their businesses or families, what their aspirations were for the future. “God willing,” they told me, again and again. And there the interview would sometimes end. Such was the level of trauma that no one was willing to speak with much optimism about the future. My interpreter explained to me that making such plans, or any form of wishful thinking at all was, for many Syrians, unimaginable. Assad had, in effect, made it impossible to envision better circumstances.

In one interview with a heroic journalist named Hasnaa, I was joined by an English interpreter, named Doaa. Hasnaa and Doaa were women of a similar age living only three miles apart in Damascus—Doaa in Mazzeh, Hasnaa in Eastern Ghouta, a predominantly Sunni neighborhood that was heavily bombed during the war.

At one point in the conversation, Doaa was visibly shocked by the details of Hasnaa’s story. “We didn’t know what was happening,” she confessed.

Hasnaa was direct: “How did you not know?”

It was a sobering glimpse into the complicated truths that an entire country will be working out for years. “I feel like we are meeting each other only now,” Doaa told me after the interview, referring to all Syrians. “The regime divided us all.” Part of Bashar al-Assad’s poisonous legacy is that he drove mistrust and hatred deep into a population that was relatively secular. The current sectarian violence in Syria is the net effect of this tool of control, even after the man who wielded it is long gone.

Transitional President Ahmed al-Sharaa has delivered a fragile freedom through a government that is so far supported by the majority of Syrians. But he will need their patience and time to overcome the country’s overwhelming administrative, economic, and social challenges. How much

time they have remains to be seen.

Freedom counts for a lot, even in the face of desperation. The hope that had emerged in Syria in December has come face-to-face with the longstanding and intractable realities of Syrian life. As Adil, a seventy-year-old money exchanger, said to me outside the Aleppo citadel, “If a person has waited for fifty years, of course he can wait a bit more.”

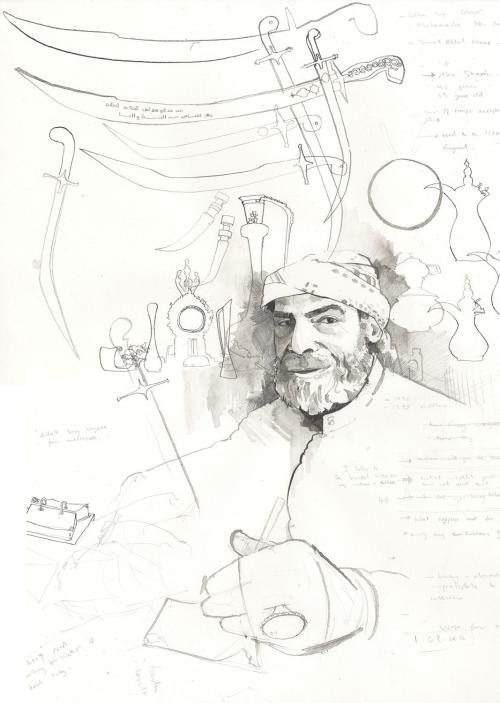

Abu Sham

Caretaker, gravedigger

Homs

I found Abu Sham surrounded by swords and brass pots in his office in the middle of the Tal al-Nasr cemetery. By his estimate, he’d buried more than 150,000 people in his nearly forty years as a gravedigger, a fact reflected in his massive hands. Hands thick as mitts. The grandfather of the graveyard, as he was known.

Under the old regime, he was arrested and beaten many times for disclosing to families the details of where their loved ones were buried, which he considered a moral duty. He would wash and prepare the body for burial and pray over the deceased according to religious tradition. He possessed enough pride (or vanity?) that meant painting his portrait was easier than interviewing him. He was very excited at the prospect of having a picture for his wall. Meanwhile, he told me about some of those he’d buried here and why he remained committed to this job.

As a gravedigger in Syria, it is important to treat everyone with respect, regardless of sect or belief. The dead are first collected by the army or other government security branches and then are transported to the military hospital, after which they are delivered by refrigerated truck to Abu Sham for burial. Sometimes the bodies are just found on the street, he told me. With no ID on them. Some had been tortured. Others died of disease, and some just died in prison. Plenty were executed.

Abu Sham was a wonderful storyteller, and he used it to deflect from the sadness of his role. The phone would ring, or another family member would enter, and the plot would be lost. He was a master of insinuation, which I assumed he had learned from surviving the regime.

We are affected by all these dead, he said, because they are our sons, our people. And they were fighting for us, fighting the regime. Sometimes we would see a whole family arrive here dead—father, mother, and child.

I know a lot of the deceased because I am well known here in Homs. They were friends, they were from families I knew. And sometimes I would go and tell a family: I buried your sons.

There is a religious belief among Muslims, that if you help to bury someone, you will be rewarded in heaven. Everybody is going to die, and no one is taking any money with him. So when I am burying those people, I am reaping rewards from God.

Our goodbye took almost as long as the interview. He kissed me on both cheeks like an old friend. Don’t forget to send the painting. I will be waiting, he said. The recent sectarian violence in Homs has meant Abu Sham’s role as grandfather of the graveyard continues.

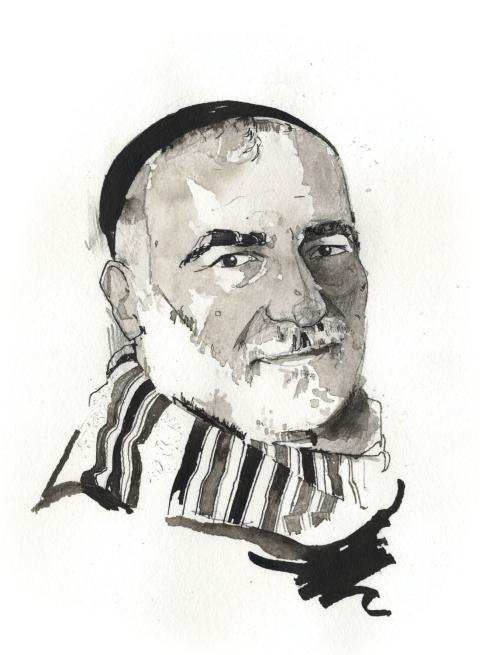

Father Jihad

Superior of al-Khalil monastic community of Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi

Mar Musa, al-Nbak, central Syria

Jihad first visited the Mar Musa monastery in 1996, when he was nineteen. He was mesmerized by the spirituality of the building. Although he didn’t return for another three years, when he became a monk at age twenty-two, his mind was never far. In 2013 Jihad took over the role of superior from Father Paolo Dall’Oglio, a very popular figure who’d been kidnapped by the Islamic State and was presumed dead.

Jihad estimates there to be around 250,000 Christians left in Syria. They are not well armed for self-defense, nor do they carry much political weight. Diplomacy is the strongest tool at their disposal.

This is a monastery, so I’m the superior or the abbot, he told me when we met in the beautiful stone monastery high up in desert hills. But I’m more often referred to as the servant of this place. It is impossible for the Christian Church to survive in Syria if Christians perceive their presence as being against Islam, or even being in competition with it. We will survive and flourish only if we understand that our prosperity is tied to the prosperity of the Islamic world in which we live; that our good is their good.

For many years the Baath regime used us, the minorities—Christians, Alawites, and others—to protect themselves while pretending to protect us. But protecting us from whom? From Sunni Muslims? We have been here for 1,400 years. If Sunni Muslims wanted to kill us, they could have done so already.

The Assad regime disseminated division and fear, which Christians now are not able to overcome. They cannot analyze this fear. They just fear. When the Kurds and the Druze see the Salafists, with their long beards and no mustaches, affirming their identity and humiliating others and also carrying out massacres of the Alawites in the coastal region, they don’t give up their weapons, because they are afraid. But Christians have no weapons.

The Christian community trusted the Assad regime only because it appeared to be a nonreligious regime that would let us eat pork and drink wine and wear short skirts, he said jokingly. But every single Christian person or Syrian person knew that the regime was a hyena—the worst monster to have to confront. But the people supported them for many reasons: for fear, for opportunity, out of ignorance.

There is a tension, and this tension, I think, is temporary. Slowly, slowly, what has boiled over should settle, and this will happen when we have a good economy, when people can work and eat with dignity.

I’m optimistic and positive. It’s not something that will fall from heaven, but I’m hopeful that if each one of us does his best, if we think together, reflect together, reach toward each other, everything is possible.

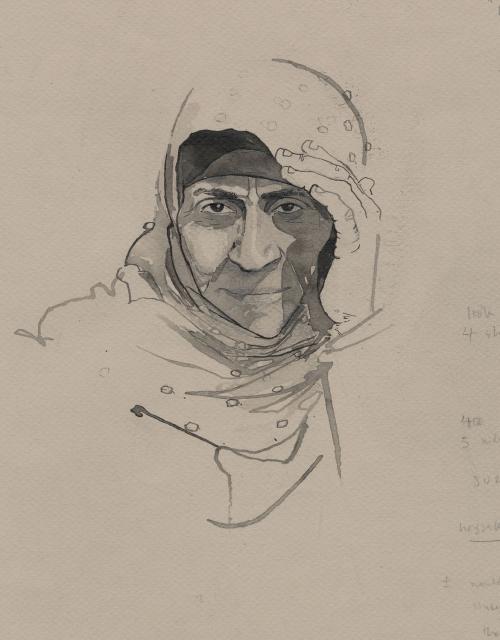

Suria

Bedouin, mother of five

Sweida

I met Suria and her husband, Rasheed, thirty minutes outside of Sweida. They lived with their five children in tents not far from the road on flat agricultural land ploughed or planted with olive trees. They are bedouin. They’d left al-Hasakah nine years ago for fear that their son would be forced to fight in the war, and they had yet to return home.

They enter the house and take your son from you, Suria, forty, said, describing some of the Kurdish forces’ methods of recruitment. Now we’re always looking for work, and we move where we find it. We made a deal with the landowner here: They give us water, electricity, and the space to stay, and they also protect the land. And when we work the land, we get some money.

Nothing has changed, even after Assad, Suria went on. The dollar has dropped a little bit. All the aid gets stolen and none of it reaches the poor. The poor in this country have no advantage.

If I had money, I would leave Syria. I want to go back to al-Hasakah, but only if the Americans and the Kurds leave the country, because they’ve been a bad influence. The only hope is for the [Syrian President] to discuss it and make a decision for the Americans to leave our lands.

I hope I get the chance to speak to those in power, the president included, so that I can tell them to come and see our situation. I want the new government to take over so that the economic situation can improve, so I can have food, she pleaded. The most important thing is to put pressure on the Americans to leave.

Abu Ahmed

Mechanic

Al-Sakkari, Southern Aleppo

Abu Ahmed’s mechanics shop looked ordinary enough. Through the open shutter I could see neat rows of spanners and a workbench. But perched on the vice and on the generators that he was mending sat a dozen domesticated pigeons. Some of the birds had brown markings and elaborately shaped tail feathers. On the walls hung little bird cages with canaries and finches flapping about inside.

I don’t really like talking to people much, so I keep birds instead, Abu Ahmed said, sitting outside his shop, waiting for work. For someone who didn’t like people all that much, it was remarkable how many people walking along this little street in al-Sakkari talked to him. He chatted constantly, providing a chair for anyone who hesitated, including me.

I have found that people who have known suffering often keep animals or gardens, especially after the trauma of war or great sadness. I couldn’t resist making a drawing.

Abu Ahmed (literally, “father of Ahmed”) is one of the more common names in Syria, but it was the way he repeated it that first hinted at the sadness in him. We talked about mundane things: the prices of eggs and the availability of petrol. These were relevant metrics for Abu Ahmed’s life. I have been saving up to build a second room in my house for ten years. I still haven’t done it, but the cost of eggs has dropped to 35,000 Syrian pounds a carton from 75,000, and the Syrian pound is up on the dollar this morning. Sometimes I can sit for five days without work.

I have six daughters and one dead son. He was fourteen years old and his name was Ahmed Osama. He was killed by a mortar round twelve years ago, in an area called al-Hamdaniya, in Aleppo. Abu Ahmed explained that the mortar was from the Syrian Army but that they always denied it, saying it had come from “terrorists”—a catchall term for anyone who opposed the Assad regime.

This week has come as a spiritual relief, he said, miming the weight being lifted off his chest and heart. For the first time he will be able to visit his five grandchildren, who live close by but were kept from him by the front line of fighting, which divided Aleppo in two. Such reunions are commonplace now that the Assad regime is gone—thousands upon thousands of people reconnecting with loved ones after many years apart. Some simply couldn’t afford to travel, others were hours away, internally displaced, or refugees.

Abu Ahmed returned to the subject of his son. He was the only one who could support me, he said. He was my wings.

Just then, one of the pigeons perched on the workbench flapped its own wings frantically, and a man pulled up with a generator he wanted repaired. The mechanic got up, smiled, and went about his work.

Ghada & Tyseer

Parents of Ghiath, Hazem,

and Anas

Darayya, Damascus

Ghiath Matar, a tailor, was a defining figure in the Syrian revolution. He was tortured and killed by the Assad regime for organizing peaceful protests and delivering food parcels in Darayya, a suburb of Damascus. The former government considered Ghiath a “terrorist,” but, as his mother, Ghada, told me, he was better known as the “ambassador of roses” for laying out water bottles with roses attached to them as peace offerings for the security forces who came to intimidate protesters. He was just twenty-six when he died, in 2011. His funeral was attended by five ambassadors. The graffiti around Damascus solidifies his leadership position in a nonviolent Syrian revolution.

I spoke to Ghiath’s mother and father, Ghada and Tyseer, who welcomed anyone wanting to talk about their son, reminding me that his brothers were also killed. Hazem was tortured and died in Sednaya prison in 2017; Anas was arrested and never seen again.

Ghiath left behind his pregnant wife; their son would be named in his honor.

The Syrian revolution didn’t start because people wanted bread, Tyseer told me. People rose up in the name of dignity and for their lives. Ghada added, If Ghiath’s fate stopped the bloodshed in this country, or spared other youths their lives, then yes, I could have forgiven. But for me, now, I cannot forgive. My happiness is incomplete so long as Assad remains free. I will never feel satisfied until they bring him to court.

They detained me before detaining Ghiath, Tyseer told me. To put pressure on Ghiath, because they were looking for him but they couldn’t find him. They took me to one of the security branches. I remember sitting in a room with all their torture devices. I can’t deny that that day they treated me well. They didn’t torture me. But they wanted me to send a message. And I remember while sitting in that room, there was a door in front of me. I saw a prisoner inside. He was sitting on a chair that had a hole in the seat and there was a candle under his genitals. He was screaming in pain.

After three days, they called me and they told me, “Your son is in the hospital. You can come and visit him.” I went inside and noticed that there was a bullet that had entered his body on one side and went out the other. And it looked like it was an explosive bullet. It didn’t look like they were taking care of him, because there were no bandages on his wounds. They told me to leave the room, and they went in to try to give him some electrical shock—I remember when they did it. It did nothing. But he took one last breath before he passed away.

We hope for a better future. There is nothing darker than the past, but we hope that things work out.

Hamdo

Weightlifter

Binnish, Idlib

Hamdo was paralyzed from the waist down at the age of five because his parents neglected to vaccinate him against polio. Otherwise, he was remarkably strong—broad-chested, with a fireplug neck. His delicate glasses were perched on his nose. We sat on his rooftop among the bees and canaries he tended. His brother and niece were there; she served us tea. They’d just returned from England, where they’d lived for years under UK passports, anxious to return home. Like many families in Syria, theirs had survived the last decade by the grace and reliability of remittances from abroad.

As a child, Hamdo was well aware of the embarrassment many families of the disabled felt. At that time, parents of people with disabilities would often keep them in the house, they wouldn’t show them to anyone. Hamdo’s family was different. My parents insisted that I should study. And he did so until the age of sixteen. After a brief period running a shop, he returned to school to prove to himself he could do it. I went and opened a little tiny store. I started fixing electronics, alongside selling, you know, groceries and stuff. When he returned to school, he failed his ninth-grade exams six or seven times before finally passing. I did it just because people told me I couldn’t do it.

As a young man, Hamdo began weightlifting as merely a hobby. I was just training casually at a gym when my coach suggested that I compete in a championship, in Latakia. I actually just said yes because I wanted to see the sea. We were so poor we could never afford trips to the sea. In 2006, after six years of training, still dreaming of the sea, Hamdo competed in an international championship in Malaysia. I won my first and only monetary award, which was $500. I came in second place.

For all the championships he has won—one hundred and seventy of them—he never received any support or recognition from the Assad regime. In 2012, as the barrel bombs began to fall, he put his expertise as a competitor to use in another endeavor, opening his home to treat those who had been wounded in the war.

Hamdo now advocates for people living with disabilities. I feel like the disabled sacrificed the most during the revolution. We are now an even greater percentage of the population, because the war created many more disabled people. We gave a part of ourselves, physically and spiritually.

Some people say that I’m the embodiment of contradiction, he said. How can I be paralyzed but also travel? How can I be paralyzed and weightlift? I’m proud of that. I think we should go out and feel things and see things and experience things, because no matter the hardships we go through life can always be more beautiful. There’s this phrase I always used to say: Spring is coming. And when we finally toppled the regime, I kept saying it to everyone around me: Spring finally came!

He looked at the canaries chirping from their cages, gestured to them. These are the wings that I fly with, he said.

No matter the path I take, I can’t deny that I lost thirteen years of my life to war, to the regime. If this hadn’t happened, and if I continued training, I could be lifting at least 250 kilograms. And yes, that’s a dream of mine, to lift again, but it’s a dream after all. And I do believe that my own spring is coming.

Ibrahim & Manal

Parents of Tariq

Damascus

Ibrahim and his wife, Manal, sat next to each other, apprehension on their faces—not so much out of fear for what might happen but for how the story they were about to tell me would make them feel. Ibrahim spoke gently, on their behalf.

In late 2000 Ibrahim was imprisoned in the al-Fayhaa security facility, charged with delivering sensitive information to staff members at the Turkish embassy. What he had actually done was make them a grill for their embassy barbeque. He was sentenced to solitary confinement for three months, then “interrogated” for fifteen days: No questions were asked of him; they simply beat him.

After that, they started administering electric shocks through my feet. They took my clothes, leaving me in my underwear, and I was always blindfolded. He was then subjected to the notorious torture method called the “flying carpet,” in which the victim is strapped to a collapsible wooden board, which is then folded shut, forcing the victim’s feet and head closer and closer together. This was at the beginning of 2001. After nearly a month, my hands became paralyzed. One man told me, “You will wish for death,” because the torture was constant, every moment of the day. I started saying whatever they wanted to hear. I told them I went to see someone from the PKK. They imprisoned me in Sednaya and then transferred me to Adra at the end of 2011.

Four days after Ibrahim’s arrest, Manal was arrested. She was eight months pregnant at the time. She was held at the al-Fayhaa security branch for five months, where she was interrogated about her husband and his suspected affiliations. During her interrogation, the guards tried to make her miscarry. She was allowed out for one day to give birth and was returned to prison immediately thereafter. Manal kept her son, Tariq, for a year and a half, but was then told he would be sent to an orphanage. Manal told them she would kill herself if they went through with it, so they sent Tariq to family members instead. For years, Manal had no news of Tariq’s fate. Ibrahim, meanwhile, wasn’t even aware that his wife was in prison. More than a decade later, the couple were allowed to meet, as they were held in the same prison, but they weren’t reunited as a family for another decade after that—not until December 2024, after the regime had fallen.

My father died before we were allowed visitors, Ibrahim told me. When he got out, he recalled, everyone was older. I didn’t recognize anyone from my family. I saw my mother once, and then she passed away. Tariq lives with us now. He studied IT and is working.

When I got out of prison, it felt like a dream, a different world. I still have the same shop. I saw my wife on that same day. I wished I had been tortured instead of her suffering. I wish I had died rather than knowing she had been in prison.

Janseet

Journalist

Damascus

Janseet worked tirelessly, and secretly, to expose the crimes of the Assad regime. Her disguise? Simply being a twenty-two-year-old Circassian woman the government assumed would be no threat. When the revolution started, she told me, I was eleven, living in Damascus in a very safe area called Rukn al-Din. We heard the bombs dropping, but it didn’t affect us. And because we lived in this safe area, many displaced people came here. So I wrote short stories about them when I was thirteen. Then I decided to study journalism.

During my studies, I realized that I had two choices: work for the state media or the Iranian media. That’s when I started communicating with foreign media companies. They started to give me many assignments, working on investigative projects. I was only in my third year of college. Most of the time, they would tell me to interview victims and get them the information that they needed.

Many of these investigations resulted in sanctions against Assad’s regime. For example, there is a psychiatric institute in Syria that also treats drug addicts. I found out, however, that illegal drugs are smuggled into the treatment center with the full knowledge of its manager. And of course these drugs would interfere with the patients’ rehabilitation. My priority now is to document the crimes of the Assad regime because there were so many that weren’t documented.

No one ever suspected me. In many people’s minds, there are certain standards you’d have to meet to be part of the revolution. In their view, to be a revolutionary, I would have to be from a certain sect, or a certain religion, from a specific minority.

The thing that made me feel the most sorrow was when I felt alone. You’re convinced that no one else thinks the way you do, that you can’t share your ideas or feelings with anyone. That was the hardest thing.

The new regime is still unpredictable, but it’s definitely better than Assad. But after what happened on the coast, the massacres in Latakia, I’ve started wondering if we’re simply dealing with a new version of Assad.

So yes, the situation is unstable, but at least I can finally say out loud that I’m a journalist. I’m not alone anymore. I am surrounded by journalists who work for the same causes that I do. I once saved 400 euros to leave for Germany as a refugee. Now I will never leave.

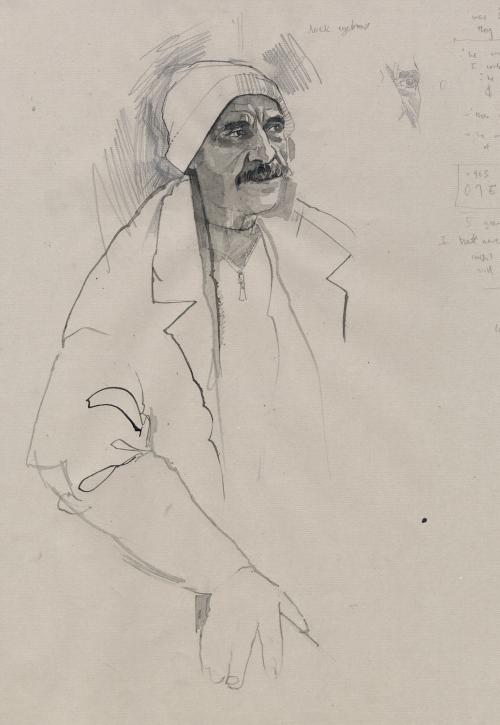

Mohammed

Stable hand

Kefraya, Homs

I met Mohammed at the stables where he made it his business to care for the two dozen horses here better than he was ever treated in prison. He sat on a chair in a concrete corridor, with the stable doors open to allow the horses to exercise and feed in peace. Light pushed through small, grated windows high up the walls, an eerie resemblance to all the photographs of Syria’s prisons that flooded the news in early December.

Mohammed was arrested at sixteen while trying to flee Kefraya village with his family caught in heavy fighting between the rebels and the government forces. He was injured in the violence, and at a security checkpoint, Assad’s forces assumed he was a rebel. He was put in solitary confinement, tortured until he provided a false confession, and then sentenced to twelve years imprisonment on terror charges.

What they call “interrogation” happens at night. They would call my name, blindfold me, and I remember that it smelled like diesel. They took me to the interrogation room and I was hung by my hands and beaten up. I was beaten in my crotch. It’s called a “confession,” but I didn’t confess truthfully. I just agreed to the crimes they wanted me to admit to—attacking security checks, shooting at the army, abducting soldiers from the checkpoints, killing, raping, whatever they wanted. I was so young that I didn’t know anything other than home and school and coming to the stables to work with the horses. I knew nothing beyond my world at the village. Their investigation took one week, until I agreed to everything.

Mohammed’s brother was killed fighting against the regime. His father was kidnapped in 2013, never to be seen again. Five other men in his family were also killed, presumed dead, or disappeared. Since the fall of the regime, I am extremely happy, but my happiness is incomplete because we were hopeful that the rest of the family would get out. I was hopeful that my father would turn up.

Mohammed talked about the ways in which the prison and the stables appeared eerily similar but was quick to distinguish them. When I open the door in the morning, the horses start neighing. They keep on neighing until I get to them. When the cell door opened in prison, people would push their backs up against the wall. That’s the difference between terror and love.

There would be no life without horses, he added. I see in them hope and optimism and happiness. Hope exists.

Hasnaa

Teacher, activist

Eastern Ghouta, Damascus

In 2011 Hasnaa was pregnant with twins, living in Eastern Ghouta, a Sunni area of Damascus. By the time she was full-term, her husband, a Palestinian Syrian who worked for the state, left her, accusing her of being a “terrorist” because the students she taught came from Sunni families. Not long after giving birth, she began joining protests against the regime In 2015 she was arrested. She was transferred from one security branch to another—five in all—the most notorious of them being al-Khatib, where she was beaten and forced to watch others being tortured. She shared a two-by-two-meter cell with fourteen other women.

Hasnaa suffered from chronic health problems but couldn’t receive treatment during her confinement, which led to her having a hysterectomy after her release three months later. When she returned home, she lived under siege for three years. Finally driven from her home by the government’s bombing campaign, Hasnaa moved her family to a nearby shelter in Harjalleh. It had five thousand rooms; no one was allowed to leave. The twins were seven. We spent the last two months of 2018 living underground, she told me. My children didn’t know what a banana was, or an orange, or chocolate.

Hasnaa discovered her name was on the list for arrest by many security branches and decided to escape the camp with the twins, spending two days in the village of Qatma near Aleppo and bribing her way through checkpoints in order to start a new life in Azaz, in north Syria. She worked to establish a network of several dozen female journalists reporting only on women’s issues in Syria, known as the Akhbarna Network (“Our News Network”).

Every sect, whether Alawite or Sunni, has made its own mistakes. For example, those who oversaw my torture and my brother’s torture in prison were both Alawite and Sunni men. But not all Alawites are bad; I have Alawite friends who oppose the Assad regime. Even though Alawites killed my brother and imprisoned me, I do not want to become like them by seeking revenge. I want Syria to be a country governed by law, where I can obtain justice by holding them accountable through a fair and impartial judicial system.

I do not want Syria to remain in a state of constant fighting among its own people. I do not want my daughters to grow up in a country at war or to lose them due to ongoing cycles of vengeance and killing.

Even my other brother, who lost his legs because of Assad’s crimes and the actions of the Alawites, does not want the war and fighting to continue between us and the Alawites. He wants a better future for his children.

In December of last year, Hasnaa returned home for the first time since fleeing in 2018 with her daughters, now thirteen. Her commitment to the Akhbarna Network remains as tireless as ever. Syrian women should not accept leadership, social, or political positions that are less than what they truly deserve, she told me. Women must support each other by forming alliances, groups, or unions through which they can advocate for their rights and stand up for oppressed women’s causes.