Awe and Splendor

The spring of 2005 was one of the happiest periods of my life, even though, at the time, I was miserable. The immediate causes of my misery were my troubled long-distance relationship and a growing realization that my career wasn’t proceeding to plan by transforming me into an internationally beloved best-selling author and millionaire. At the same time, I’d published two books, with a third forthcoming, and was being asked at least twice a month to write for some of my favorite magazines on a wide array of subjects. My dream of being a professional writer, which I’d been pursuing in earnest since I was a teenager, had objectively come true. This wasn’t misery, not really. This was happiness, hiding. Nevertheless, the nagging dissatisfaction I felt made me uniquely seducible by the figure who was about to come, however briefly, into my life.

On the afternoon of March 6, I sat down at my computer in my Manhattan apartment, opened my email, and (probably, likely) gasped when I encountered this:

what a terrific letter you wrote.

the truth is, probably i don’t want to do it.

but if you would like to have lunch and talk

about it, that would be swell. i am gone for

the next ten days, but if you want to call after

that, please do. 212-2 █ █ -1█ █ █

It was signed “bill goldman,” as in William Goldman—novelist, screenwriter, and, by this point, cultural icon to the strange souls who perk up during film credits. I’d written Goldman several days earlier, after a conversation with a magazine editor, who suggested I write something about Hollywood and what was wrong with it. At this stage in my writing life I rarely allowed my ignorance of a subject to prevent me from addressing it at length, but the fact remained that I still had to come up with an interesting angle on this most evergreen topic. Back then, virtually everything I knew about Hollywood had been siphoned from Adventures in the Screen Trade (1983) and Which Lie Did I Tell? (2000), Goldman’s twinned meditations on his life as a screenwriter. So why not approach him?

Goldman and I shared a publisher, which made it fairly easy to sneak his email address. I then wrote him a letter outlining my idea: He and I would go to the movies together for a week and, afterward, he would explain, and I would transmit, exactly what was wrong with Hollywood. Because I was thirty-one years old and self-centered, it never occurred to me what an outrageous ask this was. It helped that I doubted I’d hear back from him.

Goldman’s biographer, Sean Egan, notes that Adventures in the Screen Trade “had a peculiar effect” on its author’s aura. The book was published at a time when Goldman’s screenwriting career had cooled—permanently, Goldman sometimes feared. However, thanks to Adventures, one of the most candid and entertaining Hollywood memoirs ever written, Goldman was suddenly, in Egan’s words, “anointed World’s Greatest Expert on Screenwriting.” Incredibly, Goldman retained his standing as World’s Greatest Expert on Screenwriting for decades and almost always obliged pestering journalists seeking one of his inimitably crabby takes on the theory and practice of Hollywood.

In 2005, I was yet another locust out to gobble up the master’s time, but I wasn’t asking for something so simple as a quote or interview. Goldman would have been well within his rights to tell me to research the latest exciting developments in go fucking myself. Instead, he told me to call him. Exactly ten days later, I did.

Before we settled into business, Bill asked me, with more than a little dread, “Just tell me something. You don’t actually want to be a screenwriter, do you?”

I told Bill I couldn’t imagine writing or wanting to write a screenplay under any circumstances. Which, at the time, happened to be true.

Bill’s response: “Thank God.”

That was what I most admired about him, I said. He still wrote novels, even after, I imagined, he had no pressing financial need to do so. Bill quickly reminded me he hadn’t published a novel in almost twenty years.

But he was rolling now. “If you write a novel,” he said, “and you get x amount of money for your labors, well, that sets up a value system: You put in a certain amount of effort, you receive a certain amount of reimbursement, just like any other worker. However, if you are lucky or talented enough to become in demand as a screenwriter, the amounts you are paid are so staggering, compared to real writing, that it’s bound to make you uneasy.”

“So,” I said, “novel writing is a way to…what? Stay honest?”

“All I know is that just being a screenwriter is simply not enough for a full creative life. If you are the kind of weird person who has a need to bring something into being, and all you do with your life is turn out screenplays, I may covet your bank account, but I wouldn’t give two bits for your soul. Screenwriting,” he said,1 is shit work.”

Which brought us back to why we were on the phone. Was there, I wondered, any chance I could convince him to go with me to the movies for a week?

“My dear boy,” Bill said,2 “if I were interested in such a piece, I would write it myself. I have written it myself. A few years back I wrote a column for Ed Kosner at New York magazine. All about Hollywood. The changes. The fading. And now, maybe, the collapse.”

Just as I wasn’t aware that he hadn’t published a novel in twenty years, I wasn’t aware he’d written a column in New York magazine on the very subject I was proposing we explore. I wouldn’t have blamed Goldman for ending our conversation then and there and braced myself for exactly that. But then Bill asked about my background, my writing, my interests.

I remember his delight when I revealed that I was originally from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. Goldman was a Midwesterner too: Highland Park, Illinois. One of his characters—Jenny Devers from his early novel Boys and Girls Together (1964)—came from a tiny Wisconsin town that, I told him, was likely not far from where I grew up. Goldman laughed and said that was probably true. “How on Earth,” he asked, “did you wind up in New York?”

The answer: like everyone else. When our talk circled back to Hollywood, Bill said it was too depressing to get into. “Movies today are just a blizzard of cuts. The bullshit is increasing. Sometimes it seems to me as if our world is getting buried in bullshit.”

Was that, I wondered, as I grabbed a pencil and opened my reporter’s notebook, an industry problem or a screenwriting problem?

“I don’t know,” he said. “Teenagers today see more movies in a year than anyone of my generation saw during their first thirty years of existence. People are tired of movies. They know too much about them. Including me.”

Goldman’s enthusiasm was beginning to dim. I took my cue and thanked him for his time. But then he asked, “Do you, dear boy, like to walk?”

I told him I did.

“Then let’s take a walk together. Central Park. Two days from now.”

That sounded wonderful, I said. What time?

He told me. Then: “Now, I’m compulsively early. If you invite me to your house at eight o’clock, I am walking around the block outside at five of eight. I will do anything to be early. So please be at least on time. At least. Where do you live, by the way?”

“Downtown, right above Battery Park.”

“In Battery Park City?” I could tell that living in Battery Park City was not a salubrious fate, in Bill’s mind.

“No, above Battery Park and next to Battery Park City. I’m on the good side of West Street.”

“What’s even down there?”

“Lots of stuff. Ground Zero. The fire station from Ghostbusters.”

“And you like it?”

Like it? I was thirty-one years old, living on my own in an apartment in Manhattan. Of course I liked it.

“I’ll see you in two days,” he said.

William Goldman wasn’t a great writer, at least not according to traditional standards. His prose, at its best, was like a milkshake: fast and tasty, with the occasional clog. At its worst, his prose could be both chatty and flat, which, like being interestingly dull, is hard to pull off. Goldman was famous for his writing speed, knocking out novels in just weeks. He was equally famous—or, rather, infamous—for his aversion to rewriting. But there has never been another writer quite like him.

He began his career with a bildungsroman called The Temple of Gold, which, at twenty-four, he wrote with what he later described as “wild desperation” over three weeks in 1956. It was published the following year by Knopf, a firm looking to capitalize on the Salinger-spawned craze for young, disaffected (and, needless to say, exclusively male) voices. In other words, a more-or-less normal beginning to a mid-century literary career. Goldman did, in fact, write more literary novels—a book a year, for some stretches—including one, Boys and Girls Together, that sold a million copies in paperback.3 Later, in the 1970s, he began to publish a variety of high-concept thrillers, some stylish and gripping and others, well, dreadful. In addition, he published two spritely fables, including his most beloved novel, The Princess Bride (1973); a children’s book with the catastrophic title Wigger (1974); and a blistering Hollywood tell-all, Tinsel (1979), that might be his finest work of fiction. On the nonfiction side, Goldman managed to write not one but two definitive books on the entertainment industry: The Season (1969), which dissected Broadway, and Adventures in the Screen Trade, which demystified moviemaking.

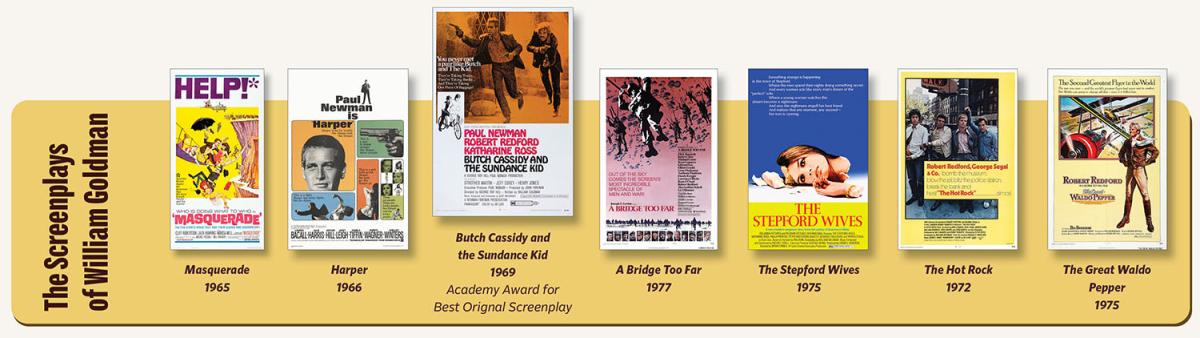

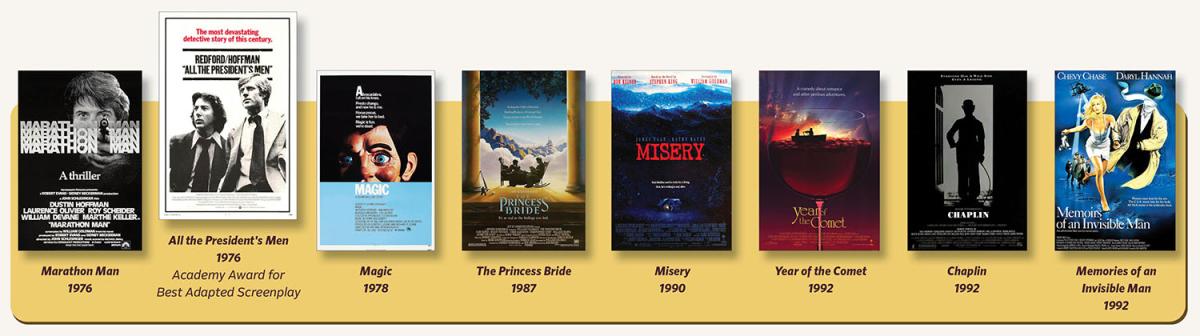

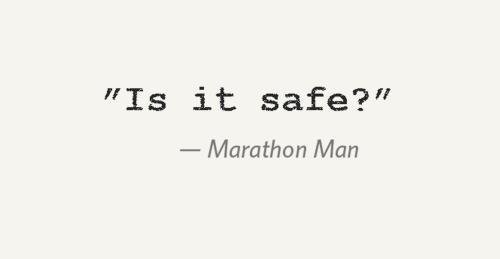

Goldman’s range as a prose writer was formidable—and left choking on gas fumes by his range as a screenwriter. Among Goldman’s film scripts you’ll find Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), which gave birth to the modern buddy picture and helped reinvent the Western; The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), a charming, elegiac, and finally quite dark film about the barnstorming days of aviation; All the President’s Men (1976), which streamlined a true-life story that was both insanely complicated and overly familiar, and, as a difficulty bonus, happened to be about Watergate,4 the most significant American political event of the preceding hundred years; A Bridge Too Far (1977), an old-fashioned World War II story about the Allied forces’ largest military failure, which ran three hours and had at least a dozen starring roles; Magic (1978), a clammy, creepy psychological thriller about a murderous ventriloquist’s dummy named Fats; and Misery (1990), one of the finest adaptations of Stephen King’s work ever filmed.

Most screenwriters, even very good screenwriters, go to their graves without having imprinted a single line of dialogue onto the American cultural consciousness. Goldman did so multiple times. One of his most lasting and influential aperçus wasn’t found in any script. It came, instead, from his book Adventures in the Screen Trade: Nobody knows anything.

In the roughly thirty-six hours I had before meeting Goldman, I read and watched as much as I could, though I’d already absorbed quite a bit of his purely literary output. When I was thirteen, I found a brittle, yellowed paperback of his 1974 novel Marathon Man in a dreary lakeside rental to which my family had been banished during a home renovation. I read it, loved it, watched the movie, loved that, and was happily launched on a long Goldman binge, which perhaps culminated with my discovery of The Princess Bride. But his industry-excoriating columns, which had appeared not only in New York but also in Premiere and Los Angeles Magazine, were litterae incognita to me. As I worked my way through them, I frowned to see how they collectively exposed Goldman’s most Cassandra-ish and least likable side, in which the world was always afire, the movies were all turkeys, and the shores of Hollywood’s former glory were forever receding into mist.

He’d indulged this side of himself as early as Adventures in the Screen Trade, wherein he announced that 1982 was “the greatest time of panic and despair in modern Hollywood history.” Nearly two decades later, at the dawn of the 2000s, he proclaimed the 1990s to be “the worst decade in movie history.” Another column, from 1994: “I cannot remember four months that were so dreary. Not only have American films been awful, they have been timid. If the Oscars were held today, nothing would win.” That year, Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, Barcelona, Legends of the Fall, The Hudsucker Proxy, Natural Born Killers, Nobody’s Fool, Spanking the Monkey, The Secret of Roan Inish, and Pulp Fiction were all released. That’s not such a bad year for film, surely. A year later, however, in 1995, he wrote, “We have just lived through the worst ten months in the history of sound.” In 1996, he admitted, to no one’s surprise, “I don’t much like movies these days.” You sensed he wasn’t mourning the movies themselves so much as his own continental drift from the industry’s volcanically active center.

The quality of the writing and analysis in his columns varied, to put it gently. Goldman was always going on about who was the world’s biggest star and saying things like “Nobody beats Mel.” When he was in that mode, Goldman wrote like a gossip-rag columnist with an emergency IQ transfusion. Yet some of his columns were surprisingly prescient. Of Groundhog Day (1993), Goldman predicted it would one day stand as the “movie most affectionately remembered ten years from now.” Throughout the columns, Goldman was gloriously candid about movies he felt were false. His takedown of Steven Spielberg’s “phony, manipulative” Saving Private Ryan (1998), to give but one example, has the virtue of being both brutal and absolutely correct. He was also withering about what, back in 1983, he’d already started calling “comic-book movies,” while admitting he’d written a number of comic-book movies himself.

Now, what Goldman called a “comic-book movie” didn’t necessarily mean a movie about Lycra-clad superhumans. In Goldman’s view, The Deer Hunter was a logic-defying comic-book movie, whereas Bambi, which dealt with death in a candid and unsentimental manner, was not. In Adventures in the Screen Trade, he decried the films of the summer of 1982 (a few popcorn masterpieces among them: Blade Runner, The Thing) as being “all comic-book movies.” He went on: “Right now—today—comic-book pictures are only breeding more comic-book pictures, something that has never happened to this extent before.”

As I write this, I wonder how Goldman, who died in 2018, felt about Hollywood at the end. No doubt he was fractious: The thing he predicted the industry was breeding had slithered out of the petri dish and consumed the entire planet. This should serve as a reminder of the underlying paradox of being alive in time: While things can always get worse, they’re simultaneously never as bad as you think they are, if only because your time of despair is doomed to be remembered as someone else’s golden age.

Bill asked to meet next to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, one of my favorite places in New York City. I knew what he looked like, or at least what he looked like in his author photos. Early in life, as a young novelist, he had a pugnacious resemblance to Anthony Hopkins. Later, after the success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Goldman slimmed down and grew a superb bandito mustache identical to Robert Redford’s in that film. (He later reported being mistaken for Redford in public.) Over the 1980s and 1990s, his author photos indicated a gradual relaxation into literary elderhood. He was heavier now, and gleamingly clean shaven, but blessed with a male model’s striking cheekbones and a swoosh of silver hair.

And there he was—yes, five minutes early—standing at the corner of Fifth and Eightieth, watching tourists float by, wearing a long black overcoat and zippered camel-brown Brooks Brothers pullover. There was something regal about Bill’s small-mouthed face, the way he stood with head tipped back just so. This was a king, yes, but a humane and tasteful king.

“Mr. Goldman?”

His eyes widened, searched, found me. “You’re early!” He started to explain that he was always early, that if I asked him to my house at eight o’clock.…I didn’t bother telling him he’d said the same thing on the phone two days earlier. As we began our walk through Central Park, I noticed him wince a few times. He explained, with another wince, “Weak disc. The L3. It’s the most goddamn unglamorous ailment.” I didn’t understand what this meant, as my own back problems were still half a decade away, but I did know it was an affliction he’d visited upon several of his heroes. Bill’s weak back was also the reason he was trying to walk more. “Moving,” he said, “keeps everything warmed up.”

During our phone conversation, Bill had asked me what movies I’d seen in the last decade that stuck with me. I mentioned a few, only to be met by Bill’s mild scoffs. Since our conversation, though, I’d come up with another movie: Babe (1995), director Chris Noonan’s charming live-action fable about a talking pig who rises above his station. From his columns I’d learned that Bill, too, loved Babe. (He was also friends with Babe’s producer and co-screenwriter, George Miller, whose versatility—Babe, but also the Mad Max films—rivaled Goldman’s.)

“In college,” I told Bill, “I saw Babe five times in the theater. And every time, it made me cry.”

“Me too,” Bill said. “Fabulous film. It’s just so goddamned magical.”

Bill’s ex-wife, Ilene, had once said that her husband loved screenwriting not because he liked the actual work, but rather because it allowed him to socialize and be sociable. As Bill pointed things out to me in the park, I realized this was the man I was lucky enough to be spending time with that day: the voluble, interested William Goldman who liked meeting people. Maybe this was also the William Goldman I could convince to do my magazine piece with me.

Suddenly, Bill stopped and pointed out a Broadway producer, a big shot, whose name I’ve forgotten, walking along with someone. Two minutes earlier, we’d passed by Donald Antrim, the famously dyspeptic novelist and New Yorker contributor. Two quasi-celebrity sightings in five minutes. Not bad. I’m fairly certain a few people we passed recognized Bill, but the kind of person who recognizes William Goldman is also the kind of person who’d be unlikely to approach him. Bill once wrote, “I have been with a lot of famous people over the decades—it is never much fun—trust me please—and I know only this: Very few of them can deal with it.” I told Bill about my favorite New York City celebrity sighting of all time: Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins sitting on the subway next to memoirist Frank McCourt. Obviously, neither had any idea who the other was. Bill then told me about seeing James Cagney get off a bus on Fifty-Seventh Street years and years ago, which he’d written about more than once. Helpless, Goldman said, he followed Cagney for blocks, because how could he not? “That walk!”

I expressed sympathy for the followed, the seen, the noticed. Goldman frowned. “I don’t have any sympathy for stars who complain about being recognized. They chose this profession and knew what might lie ahead.” Bill had been recognized a few times, it turned out. His favorite instance was a woman who asked him—here in Central Park, not too far from where we were talking—what he was doing “in town.” He explained to her that he didn’t live Out There (his ominous synonym for Los Angeles) and that New York City had been home for his entire adult life. “She couldn’t understand,” Bill said. “She thought everyone involved in the movies lived in Hollywood.” Another myth he was eager to dispel: “People outside the entertainment business tend to assume that people in the business all know each other. Not true. Do you know when Katharine Hepburn met Henry Fonda for the first time?” I did know, because he’d written about it, but Bill was rolling again, so I pleaded ignorance. Bill’s answer, delivered with outthrust arms: “On the very first day of shooting On Golden Pond, when they were both in their seventies!”

I said maybe, just maybe, his famous maxim “Nobody knows anything” should be updated to “Nobody knows anyone.” Bill’s laugh was polite, but, I hoped, sincere. It then occurred to me how much fun I was having, and I decided, then and there, never to bring up my stupid magazine piece idea again.

Most screenwriters, even very good screenwriters, go to their graves without having imprinted a single line of dialogue onto the American cultural consciousness. Goldman did so multiple times: “Rules? In a knife fight?” “Follow the money.” “Inconceivable!” “Is it safe?” However, one of Goldman’s most lasting and influential aperçus wasn’t found in any script. It came, instead, from Adventures in the Screen Trade:

Nobody knows anything.

Goldman called this “the single most important fact” about the film industry. He meant that nobody knows why stars bring out audiences for one film but not another, why some stories capture our imagination, while other, similar stories don’t. Tastemakers and financiers can guess and rationalize, but for every seemingly watertight explanation there’s a capsized counterexample. Executives and industry watchers write off such exceptions as “nonrecurring phenomena,” even though, as Goldman points out, they are constantly recurring.

Goldman came by his signature maxim honestly. Nobody knew, least of all him, that he’d ever find success as a writer. Once he did, nobody knew he’d ever turn to screenplays, much less the wealth and acclaim he’d earn writing them. It bears mentioning that Goldman had a preposterously difficult and psychologically damaging childhood, which he almost never wrote about directly. Goldman’s father was, for a time, a wealthy businessman who worked in the Chicago clothing industry. He was also a heavy drinker whose business losses transformed him into a pajama-clad hermit who refused to leave the house. When he was fifteen years old, Bill found his father’s body a few hours after his suicide. Earlier in the day, Bill had thought to check on his father but didn’t, which would haunt him for the rest of his life. Goldman’s traumatized mother, who already had problems hearing, went completely deaf after these grim events, and once cruelly told Goldman that he was the cause of her handicap. Goldman’s older brother, James, whose difficult birth had caused his mother’s initial hearing loss, was always the family’s favored child. He, too, was an aspiring writer, like Bill, but also a star student, very much unlike Bill. When Bill found literary success more quickly than James, he was consumed with guilt: “It was like a Greek crime for me to have done what I so unforgivably did: surpass my brother.”5

After the publication of his first novel, which underperformed commercially, Goldman went into a long creative hibernation, watching movies at the Thalia Theatre on the Upper West Side for the better part of a year while doing occasional script-doctor work for Broadway shows with James. He later called this period his “movie education.”

Over the next few years, Goldman wrote more books, as well as two plays with James, both of which wound up on Broadway. His career trajectory was seemingly quite enviable: While still in his early thirties he’d published multiple novels…that were largely savaged by critics. He had two shows on Broadway…that quickly closed. Goldman always maintained that he “entered the movie business based on a total misconception,” but he was also angered by his drubbing from book reviewers. This preternaturally restless young writer was ready to try something new.

The “misconception” that dragged Goldman into the movies was not his own but rather that of actor Cliff Robertson, who had once starred in a 1961 television-movie version of Daniel Keyes’s short story “Flowers for Algernon,” about a dim-witted man who boosts his intelligence artificially. Dissatisfied with his stalled movie career, Robertson believed the Keyes story could become a feature-film star vehicle for himself. He then somehow got his hands on a publication proof of Goldman’s thriller No Way to Treat a Lady, which was notable for its terse prose and almost comically abbreviated chapters. When Robertson dropped by Goldman’s apartment to tell him how much he’d enjoyed his film treatment, Goldman silently wondered, What film treatment?

Goldman hadn’t read the Keyes story but was eager to adapt it. Problem one was that he’d never seen a screenplay. Once Goldman got his hands on one, he was appalled: “I knew I could never write in that form, in that language.” Goldman wound up inventing his own idiosyncratic screenplay format, which he’d use for the rest of his career. Before Goldman had finished his Keyes adaptation, Robertson called again to say he’d been cast in a spy film called Masquerade that was trying to capitalize on the success of the first James Bond film. The lead had been originally written for Rex Harrison. Now that Robertson was aboard, its dialogue needed to be “Americanized.” Would Goldman be interested?

Of his first day on set, Goldman later wrote, “Probably I have been more excited in my life, but not often.” His excitement quickly gave way to incredulous boredom. As he’d augur years later, “The most exciting day of your life may well be your first day on a movie set, and the dullest days will be all those that follow.” Know this is not necessarily accurate. Watching an army of human beings work intently to bring stuff you wrote to life? Perhaps that gets boring eventually, but it certainly doesn’t happen right away, and it’s telling that Goldman tired of it so quickly.

After his work on Masquerade was complete, Robertson finally read Goldman’s “Flowers for Algernon” adaptation, upon which he fired Goldman, whose replacement was a noted screenwriter with a splendidly Seussian name, Stirling Silliphant, who later won a Golden Globe for the film that became known as Charly. Cliff Robertson, meanwhile, won an Oscar for the title role.

What Goldman called a “comic-book movie” didn’t necessarily mean a movie about Lycra-clad superhumans. In Goldman’s view, The Deer Hunter was a logic-defying comic-book movie, whereas Bambi, which dealt with death in a candid and unsentimental manner, was not.

In 1965, while on Christmas vacation, Goldman decided to write his first original screenplay. It was about the Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy, two members of a then-unheralded criminal posse known as the Hole in the Wall Gang. Goldman had been researching their story for years, reading what little he could unearth about them, with the intent of eventually writing a novel. Then he realized something: He hated horses. He didn’t even like the old West all that much. Reifying the tale of Sundance and Butch in prose meant months and possibly years of ancillary research. But screenplays don’t necessarily require that. In a screenplay, the writer merely plants the corner stakes and lays out the form boards, leaving it to numerous technical artists to pour in the cement. Goldman later admitted that “if I had liked horses, if I had written a novel, the movie never happens.” Yet the first time the screenplay went out, no one offered on it. Some studio heads objected to the screenplay’s long second-act detour into Bolivia. Goldman pretended to listen to their notes, changed virtually nothing, and sent it out again. This time, The Sundance Kid and Butch Cassidy sold for $400,000—the largest amount any studio had ever paid for a screenplay.6 Nobody knows anything, indeed.

Although initially panned by a number of critics, the film went on to become a huge hit—the first and biggest of Goldman’s long career. Bantam even published Goldman’s screenplay as a paperback, something that was commercially unprecedented, especially for a film that was just hitting theaters. After Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Goldman probably could have done almost anything he wanted in Hollywood. Instead, he went down a path that the young, ambitious screenwriter of today would regard as career-gutting insanity: He decided to write a book.

The Season was published in 1969 and chronicled Goldman’s attempt to see literally every show to hit the Great White Way over the course of a year. Some shows Goldman merely attended and commented on as an informed viewer. (Here he is on Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party, which he assailed with particular relish: “[Pinter] is appropriately obscure; he allows intellectuals to theorize.” And here he is, even more brutally, on an aging theatre wunderkind named Mike Nichols: “brilliant and trivial and self-serving and frigid.”) For other productions, though, Goldman went deeper and reported thoroughly on their backstage doings. One of the plays so chronicled was a comedy called Something Different, directed by Carl Reiner. Goldman and Reiner became friends, and for years afterward Goldman sent Reiner copies of his books as they were published.

One day, in 1973, Carl handed his son Rob a copy of Goldman’s novel The Princess Bride, telling him, “I think you’ll like this.” The clear implication was that Carl hadn’t. Fortunately, the younger Reiner was already a Goldman devotee, having read, as he later put it, “literally every book he had ever written.” In 1973, Reiner was still just an actor, playing the liberal son-in-law of Archie Bunker on the most popular television show in America, All in the Family. As Reiner read on, however, he knew, somehow, he’d one day direct The Princess Bride.

The Princess Bride grew out of the fairy-tale stories Goldman told his young daughters Jenny and Susanna—stories his wife Ilene was always urging him to write down. He resisted, perhaps worrying it would dilute the spontaneous magic of his bedtime storytelling. One day, shortly before leaving for Los Angeles on a work trip, Goldman announced that he would write a story for Jenny and Susanna, but only if they told him what they wanted it to be about. When one daughter said, “Princesses!” and the other said, “Brides!” Goldman knew he had his title.

When he first began work on the story, Goldman intended it to be nothing more than a “kid’s saga,” which explains the “silly names” (Goldman’s words) he bestowed upon his characters: a princess named Buttercup, a prince named Humperdinck, a court magician named Miracle Max, and so on. Publication wasn’t necessarily the goal. But the deeper Goldman got into the story, the more it intrigued him.

He then had the brain flash of his career. What if he inserted a false autobiography into The Princess Bride, transforming it from a self-contained “kid’s saga” to a book his father had read to him as a child? That breakthrough was swiftly followed by another: And what if the true nature of this book had been kept from him by his father? The “good parts” abridgment of The Princess Bride was born, wherein William Goldman wasn’t an author but rather a humble editor judiciously eliding long stretches of one S. Morgenstern’s occasionally interminable narrative.

Both the novel-within-The Princess Bride and its film adaptation open proper with Buttercup, who hails from the landed gentry and falls in love at first sight with Westley, her family’s farm boy. Being poor, and returning Buttercup’s affection, Westley sets out to earn his fortune to better provide for their life together. Soon, dire news arrives at Buttercup’s family farm: Westley has been captured by the Dread Pirate Roberts, a fearsome brigand notorious for leaving no survivors. Shortly thereafter, the soon-to-be king of Florin, one Prince Humperdinck, decides to marry Buttercup. She relents to becoming Princess Buttercup of Hammersmith, even though she’s decided, as a result of Westley’s death, to live her life without love, which is fine by Humperdinck. You see, the prince is secretly planning to have Buttercup murdered on the eve of their marriage in order to provoke a war with the nearby kingdom of Guilder. The kidnappers Humperdinck hires—a Sicilian, a master swordsman, and a Turkish giant—are in the middle of their Buttercup abduction when they realize they’re being tailed by a mysterious figure they designate the Man in Black. One by one by one, the Man in Black dispatches Buttercup’s kidnappers, upon which he reveals to Buttercup that he’s Westley in disguise. It turns out Westley wasn’t killed by the pirate who captured him but rather served as the man’s eager apprentice, which allowed him to learn how to fence and fight, among other things. The reunited Westley and Buttercup attempt to flee, only to be intercepted by Humperdinck. Backed into a corner, Buttercup agrees to marry Humperdinck, provided he spares Westley’s life. Humperdinck agrees, but then shuttles Westley to one of his dungeons, in which he ultimately tortures poor Westley to death. Meanwhile, Buttercup’s kidnappers—two of whom survived their ordeal with Westley and are shown to be decent fellows, all things considered—find Westley’s body, have it miraculously restored to life, and attack Humperdinck’s castle on the night of his wedding to Buttercup. Once the Princess Bride has been happily rescued, the foursome gallops off into the night.

This is the narrative of the novel and the film follows it closely. There are differences, of course. Buttercup’s miserable parents, who are never shown in the film, figure heavily in the novel’s opening. “All they ever dreamed of was leaving each other,” Goldman-as-Morgenstern tells us of the pair. One day, Count Rugen—the cruel, six-fingered aide-de-camp of Prince Humperdinck—arrives at Buttercup’s family farm, having been alerted to the beauty of its youngest inhabitant. Buttercup’s “gnarled shrimp” of a mother panics, assuming the count is there to collect unpaid taxes. The count, though, assures everyone that he’s there merely to check on the farm’s cows. “I’m thinking of starting a little dairy of my own,” he explains, ickily doubling an entendre. Rugen then lays eyes on the fabled Buttercup, who, according to Goldman’s narrator, is among the twenty most beautiful women in the world.

“Understand now,” Goldman’s narrator tells us, “she was barely rated in the top twenty; her hair was uncombed, unclean; her age was just seventeen, so there was still, in occasional places, the remains of baby fat. Nothing had been done to the child. Nothing was really there but potential.” Watching Rugen watch Buttercup is Westley, the farm boy, at which point Rugen’s wife, the countess, who’s along on her husband’s visit, takes Westley out back behind Buttercup’s farm, apparently to groom him for seduction. The sight of Countess Rugen disappearing with Westley drives Buttercup into a frenzy of jealousy, much to her own astonishment.

Soon after this, Buttercup announces her love to Westley: “Do you want me to crawl? I will crawl. I will be quiet for you or sing for you.… Anything there is that I can do for you, I will do for you; anything there is that I cannot do, I will learn to do.” Westley responds by announcing his decision to travel to America. Yet Buttercup still fails to understand why, exactly, Westley is leaving. To that, Westley laments, “You never have been the brightest.” This is not Buttercup’s only instance of moronism. Her horse, we’re told, is named Horse because “Buttercup was never long on imagination.” After they’ve been reunited, Westley mockingly asks her, “When was the last time you read a book? The truth now. And picture books don’t count—I mean something with print in it.”

I confess, while rereading The Princess Bride, I thought more than once about Goldman’s young daughters, to whom the novel’s genesis can be traced. The Princess Bride’s relentless affirmation of beauty’s importance, its odd resolve to denigrate Buttercup at every turn, goes against everything fathers should teach little girls about what they can and should aspire to. I have no idea whether Goldman was a good father—my hope and suspicion is that he was an excellent father—but my heart nevertheless cankered to imagine any little girl transdermally absorbing the insinuations of The Princess Bride’s opening pages.

It’s useful to compare all this to the beginning of Rob Reiner’s version of The Princess Bride, whose screenplay Goldman provided. Once the film has established its intergenerational framing device—a grandfather (Peter Falk) shows up in the bedroom of his sick grandson (Fred Savage) to read him S. Morgenstern’s classic novel—it cuts to an establishing shot of the rolling green swards of the Florinese countryside. There, below a wedge of powder-blue sky, Buttercup rides her horse through a verdant pasturage lined with hedgerows, toward a small farm. Falk’s Grandfather tells us in voiceover that the favorite pastime of Buttercup (Robin Wright) was “tormenting” the boy who worked that farm. Any possibility that Buttercup’s family abides with her on this land, as they do in the novel, appears to be annulled by the tininess of its two small living quarters. We then cut to the stables, with Buttercup skipping into frame while Westley (Cary Elwes) works. In a bright, imperious voice, she demands that Westley polish her saddle, adding, “I want to see my face shining in it by morning.” There’s more than a tinge of cruelty in this Buttercup, who seems oddly excited by the possibility that her beauty might also be a weapon. Westley, however, holds Buttercup’s gaze as he tells her, “As you wish.”

We then cut to Westley chopping wood. Buttercup approaches with two empty buckets, which she sets down before him. She asks Westley to fill them with water, this time appending a quiet, apologetic “Please” to her request. Again, Westley stares smolderingly back at her. “As you wish,” he says. In voiceover, Grandfather tells us Buttercup suddenly understood that “As you wish” was Westley’s code for I love you. The shaken Buttercup walks away from Westley, only to glance back at him with haunted eyes.

“The camera gives you the actor’s eyes,” William Goldman once told an interviewer, before going on to explain that, oftentimes, “eyes” are all you need in a scene to convince the viewer something momentous has happened. Despite being less than two minutes into Buttercup and Westley’s love story, Buttercup’s spooked backward glance makes us believe something momentous has happened.

When we eventually rejoin Buttercup and Westley, their love affair has progressed, apparently for the worse, for now they’re embracing while Buttercup weeps. Westley, it transpires, is leaving her to seek his fortune. “Hear this now,” he tells her. “I will always come for you.” Buttercup, her voice trembling, asks, “How can you be sure?” Westley smiles and says, “This is true love. You think this happens every day?” As Westley strides toward his destiny, Falk’s Grandfather tells us in voiceover that Westley was soon captured and killed by the Dread Pirate Roberts. We then cut to Buttercup, seated before a fire, her eyes fixed just off camera, saying aloud she will never love again. In a fleet three minutes and twenty seconds, Goldman and Reiner have shuttled us from the vague first stirrings of love to its utter incineration.

It’s easy to understand why Goldman’s script swept aside so much of his novel’s opening: None of it was dramatically necessary and some of it would have endangered the film’s precarious tonal balancing act, which is best evidenced by Westley’s “This is true love. You think this happens every day?” Westley never says anything quite so tartly self-aware in the novel, which, if anything, is far more embittered on the subject of true love.

Or take the film’s incantational use of “As you wish,” which has become one of its most beloved bits of dialogue; Cary Elwes even used the phrase as the title of his making-of memoir. All of which makes it somewhat shocking that “As you wish” doesn’t really figure in the novel. While Westley does say “As you wish” to Buttercup in the novel, and multiple times at that, she never understands why or what he’s trying to say to her. Eventually, the novel’s Westley has to tell Buttercup outright the secret meaning of the phrase.

That deflating exchange occurs on the fifty-eighth page of The Princess Bride, after we’ve learned quite a lot about Buttercup and Westley. Certainly, after three minutes and twenty seconds of exposure, few audience members would claim that the film’s Buttercup and Westley are well-realized characters (Buttercup barely achieves such status by the end of the film), much less that their three-minute love story is some bijou of profound storytelling. What we experience in the first few minutes of Reiner’s The Princess Bride is more of a bright, sunny strophe on the idea of true love than its dramatized enactment. In its review, The New Yorker referred to Goldman’s novel as an “oppressively adorable adult fairy tale,” but oppressive adorability is what the film strives to avoid. Yes, the film tells you in its opening minutes, this is a fairy tale. It will be sentimental, even simplistic. But what could feel cloying instead feels strangely elegiac. You’re moved not by Buttercup and Westley as characters but by some younger, irrecoverable version of yourself.

One day, shortly before leaving for Los Angeles on a work trip, Goldman announced that he would write a story for his daughters, but only if they told him what they wanted it to be about. When one daughter said, “Princesses!” and the other said, “Brides!” Goldman knew he had his title.

While rereading The Princess Bride and coming upon its “As you wish” revelation, which is so pathetically outshined by the film, I wondered whether Goldman had himself backward. What if he was actually a screenwriter who happened to write novels? His greatest strengths as a novelist were almost entirely ideational: structure, premise, pacing. Goldman seemed aware of this, once describing his writing to an interviewer as “the best I can do, but it’s not something that fills me with awe and splendor.” The dialogue in his novels, for instance, while clever, sometimes has the shouty emotional obviousness of mediocre playwriting. Then you watch the better adaptations of Goldman’s work, all of which he wrote himself, and there they are, the same lifeless lines of dialogue, CPR’d to life by world-class performers.

The Princess Bride performs a number of such resuscitations. At one point in the novel and the film, Westley and the Spaniard Inigo (Mandy Patinkin), expert swordsmen both, face off in a long duel. Most notable about the film’s run at the duel is Inigo and Westley’s long, friendly conversation before they fight, during which it’s revealed that Inigo has been searching for his father’s killer, a cruel six-fingered man. Westley is moved by Inigo’s story, but to pursue Buttercup he knows he must defeat Inigo all the same. As they rise, reluctantly, to battle, Inigo says, “You seem a decent fellow. I hate to kill you.” Westley’s answer: “You seem a decent fellow. I hate to die.”

An early draft of Goldman’s script had the film opening with these words spoken over black screen, followed by the clank of clashing swords, after which the film was to cut to the sick Grandson’s bedroom. Obviously, Goldman recognized the exchange as the crux of a crucial character moment, which makes the novel’s framing of the lines so striking. There, Westley and Inigo enjoy of no friendly pre-duel conversation, beyond Inigo curtly granting Westley—who’s just scaled the Cliffs of Insanity—the chance to rest. Once Westley has regained his strength, he and Inigo have their “I hate to kill you”/ “I hate to die” exchange, but it feels like an emotional non sequitur: These men have no reason to admire each other, beyond dramatic contrivance. Once the battle is underway, the novel’s Inigo desperately screams, “Who are you?” when he realizes that Westley is a vastly more talented swordsman than he’d anticipated. But Westley refuses to tell Inigo his real identity. Soon after that, Inigo screams again, “I must know!”

In the film, Inigo never raises his voice, despite speaking the same lines. When Westley rebuffs him, Inigo responds with a louche shrug and returns to the fight. The film’s Inigo knows he’s about to lose, knows he might even perish at the end of Westley’s blade, but maintains his appealingly rakish composure. The Inigo of the novel is a compelling character—an alcoholic depressive consumed by his desire for revenge—and his backstory is among the more involving parts of Goldman’s story. The film’s Inigo, meanwhile, has become a modern cinematic icon, complete with a mantra (“My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”) that 90 percent of the moviegoing public could probably recite on cue. To whom, then, do we credit the iconic Inigo? Goldman, with his canny retooling? Or Mandy Patinkin, who delivered a committed and intelligent performance? Possibly Rob Reiner, the director? Or was it all of them? Collaborative art can be frustrating, even painful. It can also be transformative when people are working together in good faith. That’s what Vladimir Nabokov refused to understand when he decried filmic collaboration as a “multiplication of mediocrity.” The novel’s Inigo, desperately screaming at his opponent, is a perfunctory first draft. But the more people who touched the character, the more interesting—the more individualized—he became.

On March 31, 2005, a little over two weeks after Bill’s and my walk in Central Park, I received this email:

IF YOU WOULD LIKE, GIVE ME ADVANCE NOTICE WHEN YOUR FIANCE IS UP, S█ █ █ █ B █ █ █ █ █ MY PARTNER OF EIGHT YEARS—PARTNER IS A SUCKY WORD BUT WHAT DO YOU CALL IT?—ANYWAY, WE WOULD LIKE TO BUY YOU AND YOURS A DECENT DINNER. LET ME KNOW IF YOU’D WANT.

BILL G

Bill and I had been emailing on and off since our walk. He’d happened to read something I published in the Guardian about my father (“FABULOUS ARTICLE ABOUT YOU AND YOUR DAD.”), and on the phone one evening—I’d called Bill to thank him for his complimentary email, but also just to talk, because we were living in a mystical era when it was possible to call people, with no forewarning, just to talk—I’d mentioned that my girlfriend, Ann, who lived in Michigan, was coming to New York for a visit.

Ann wasn’t my fiancée, however, and I was puzzled Bill had gotten that impression. When he asked how we met, I told him it was a Buttercup–Westley thing: an inarguable case of love at first sight. It wasn’t, of course. It never is. Yet at this point I believed Ann, an aspiring screenwriter, was going to be the person I finally committed to, having decided to ignore the compelling evidence that Ann had every problem with commitment that I did. Already our relationship was like an ungainly river barge that had drifted down a tributary feared for its brutal rapids. The ride was uncomfortable and often perilous, but the churn was never powerful enough to do the merciful thing and sink us. We just kept floating, bashing into things, and ignoring the waterfall we both knew was coming.

“we will meet you at gotham bar and grill,” Bill wrote a few weeks later, once my strange, unpredictable, screenwriter girlfriend had arrived in New York. And here was William Goldman, whose work she idolized, telling us where to meet him for dinner. How could this not fix us? How could this not fix everything?

Ann was nervous to be meeting one of her idols but made me promise not to mention her screenwriting ambitions to Bill. This hesitance to broadcast her ambition was what made screenwriters, then, such an exotic literary species to me. It’s genuinely hard to get a poet or novelist to not tell you what they do, much less to shut up about it once they’ve told you, but ask a screenwriter—on a plane, at a party—how they spend their days and prepare for an evocative litany of evasions. Bill plainly felt the screenwriter’s congenital embarrassment too, which is why he called himself a novelist first. The question is why—why are screenwriters so existentially discomfited? A theory: Unless you’re a writer-director, there are literally no good reasons to write a screenplay, other than money. Screenwriting is the only form of imaginative writing in which the author’s primacy is chronically downgraded. In exchange for not questioning this state of affairs, the screenwriter is paid, often handsomely. To pursue opportunities actively in such a system is literary stool-pigeonry. Screenwriters are embarrassed because what they do is embarrassing.

“That’s ridiculous,” Ann said in the cab on the way to Gotham Bar and Grill. “I’m not embarrassed. I just don’t want Mr. Goldman to think I’m here for any reason other than the pleasure of his company.”

“You can call him Bill.”

“Nuh-uh. Not until he tells me I can.”

I’d by now been proselytized into Bill’s cult of punctuality. Ann and I arrived five minutes before Bill and S, which I’d predicted, accurately, would be ten minutes before our reservation time.

“Call me Bill,” Bill said to Ann within seconds of meeting her. As for S, Bill’s longtime companion, I realized, while shaking her hand, that I’d seen her picture many times in the New York society pages over the years. S was a widow and had enough personal wealth to have settled into the indolence of a finer Upper East Side existence. But that was not her way. No, S was a woman who did things. A connector, a doer, a donator, a party-thrower for worthy causes, a person of obvious taste and refinement. But funny too. Warm. Rich people I can handle, but wealthy people I almost never cotton to. I liked S from the start. How wonderful Bill had found a partner so eminently equal.

The maître d’ soon spotted Bill. A long coronation began, ending with the crown of a reserved second-floor table, which overlooked the first floor. Bill knew every waiter’s name and they obviously revered him. No one was as “fascinated” by restaurants as he was, Bill had once written, and he was fervent in his belief that New York was the greatest dining city in North America. As he studied the wine menu and asked what we were “in the mood for,” Ann gripped my hand under the table. She’d been afraid Bill would ask about wine. Ann, who knew slightly more about wine than I did—which was nothing—suddenly volunteered that she’d loved Year of the Comet, Bill’s much-maligned 1992 caper flick. As Ann knew, the film was entirely the product of Bill’s adoration of red wine.

“Oh?” Bill said curiously, lowering his wine menu. Ann’s gambit had worked. Rather than press us on our wine preference—“Red,” I thought, would have covered it—Bill began talking about his doomed movie, in which the most valuable bottle of wine in the world is chased across multiple countries. Originally written in the late 1970s, Year of the Comet was Bill’s first produced original screenplay since Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. It was shot when he was still deeply involved with Rob Reiner’s production company, Castle Rock, a relationship that began with The Princess Bride. Despite such congenial portends, Year of the Comet nevertheless became what Bill later called “an all-out fucking fiasco.”

Bill, genuinely curious now, asked Ann what she liked about Year of the Comet. Ann told him she loved its sense of humor and adventure, after which Bill fired a quick, imploring glance (Keep this one) my smiling way. Then he said, “At the first test screening, I realized—and this is absolutely the worst realization a writer can have—that I wrote it for myself. I was literally the only person the movie had been made for.” By this point, S was rubbing Bill’s back: The film’s reception remained for him an emotionally gangrenous wound. “There was nothing we could do to fix it. Not in editing, not by changing the score. Because no matter how and where we fussed, we’d made a movie about red wine, and today’s moviegoing audience has zero interest in red wine. You should have seen the test scores! They hated us.” (During a press visit to the set, Peter Yates, the film’s director, had disastrously proclaimed, “I hope that we prove in the film that wine is better for you than computers.”)

I asked Bill if a film like Comet would have benefited from being directed by, say, the person who wrote it. “No, no, no,” he said. I pointed out how many great directors had started off as writers: John Huston, Preston Sturges.… “No,” Bill said again, gently cutting me off. “Look, I never wanted to direct. I don’t understand actors. Most actors are phony, so there’s not much to understand. I don’t like actors, for the most part. When I was on my hot streak, people kept asking me to direct. It was ridiculous. But I never felt that pull. I always had exactly as much power as I needed. It’s not like writing isn’t hard enough! To pile directing on top of that?”

After the Burgundy that Bill ordered had been poured, he dove back into this topic: “The first thing I tell young screenwriters”—and here I squeezed Ann’s hand; she was so rapt she didn’t notice—“the first thing I tell them is this: Kids, I don’t know what I’m doing. Because if I knew what I was doing, everything I write would be good. It’s not, as has been conclusively established in the press.”

Eventually, S asked if we’d lately seen any movies we admired. Ann immediately offered up Million Dollar Baby, the Clint Eastwood–directed boxing-flick weepie from 2004. In apparent agreement, S’s hand leapt to her breast. “Fabulous movie,” Bill said. “Marvelous movie.” He didn’t bother telling us that he’d known Eastwood for years and had even worked with him, most recently on Absolute Power (1997), an adaptation of David Baldacci’s 1996 government-corruption potboiler, which, despite being directed by Eastwood, written by Goldman, and starring a number of wonderful actors, is perfectly awful.

Bill wrote about his experience adapting Baldacci’s novel in Which Lie Did I Tell?, explaining that, before he took the assignment, he believed a screenwriter’s decision to adapt a book necessitated “caring for and being faithful to the source material.” Yet Absolute Power—the bonkers narrative of which contains three films’ worth of characters and yet, somehow, no obvious lead—shattered Bill’s devotion to this internal diktat. While flailing on the script, Bill turned in desperation to his friend, screenwriter Tony Gilroy, who urged him to forget about the source material. Goldman resisted such a drastic step. Gilroy’s response: “I haven’t read the novel—My main strength is that I haven’t read the novel—The novel is killing you.” Goldman wound up chucking and altering major elements of Baldacci’s story, which caused him to readjust his thoughts on literary adaptation. A screenwriter, he concluded, “should not be literally faithful to the source material. It is in a different form, a form that does not have a camera.” What the screenwriter ought to do, he wrote, was remain “faithful to the intention of the source material.”

Strange that Bill would go on the record as having learned this only by the 1990s, because the wisdom of Gilroy’s lesson is apparent not only in The Princess Bride but also many of Bill’s finest adaptations: All the President’s Men, Marathon Man, Misery. But were any of these thoughts true? If faithfulness were the point of adaptation, why wouldn’t we simply rest content with the original source material? Why adapt it at all? The word adaptation comes to us through French from Latin: adaptare, “to fit.” The word’s very root implies untested novelty and newness. Surely, the most honorable thing an adaptor could do was maximize the virtues and minimize the flaws of the source material. But honoring its intention? Who could faithfully dowse that subjective phantom from hiding? Adaptation creates its own intention.

We all evidently enjoyed ourselves during the meal, because the next thing I knew Bill was inviting us up to his apartment, which was only a few blocks from the restaurant. I remember how Bill’s heavy, solid-wood furniture seemed like a material counterpoint to the spaciousness of every room. I remember walking through Bill’s bedroom to reach his stone patio.7 (“Look,” Ann whispered, pointing out one of my books on Bill’s bedside table, as though I hadn’t immediately noticed the same thing.) I remember thinking, while standing on Bill’s patio and looking down into his building’s atmospherically spotlit inner courtyard, that this was a place to declare the formation of a new government or announce victory in a short, decisive war. I remember Bill saying, “Oh, hiya, Tim,” after which Ann and I turned to see director Tim Burton and actor Helena Bonham Carter orbed in milky orange candlelight on their adjoining patio.

Before leaving, Bill stood us before what he called his most “cherished personal object.” A tapestry—seven and a half feet tall and six feet wide, made of silk thread and wool, and designed by a textile artist named Carol Burland—that illustrated several scenes from The Princess Bride. These weren’t the famous scenes from the movie; the characters looked nothing like their filmic counterparts. Bill’s choice. There was the six-fingered man in Humperdinck’s castle. A severed rope dangled over the edge of the Cliffs of Insanity. Inigo and the Man in Black dueled—and the Man in Black was wearing a hood, as in the novel, and not a Zorro mask, as in the film. There was Fezzik the giant with the ample mustache the novel granted him, as had Bill’s script.

The night somehow ended in S’s nearby and even more palatial apartment, where I held in my hands a first edition of The Great Gatsby. Tears came to Ann’s eyes when I opened the book and discovered that it had been inscribed by Fitzgerald himself. “In my entire life,” Bill told us, “there was no project I wanted to write as much as Gatsby. It’s such a desperately moving book.”

Bill walked us to the SUV of his personal driver, who was waiting down the block. We were all drunk and happy, which made it too easy to fall into Bill’s arms and thank him for the evening. Rolling down West Street, toward my apartment, in that huge, smooth-rolling chariot, New York City seemed like a blessed cathedral of light and possibility. It would keep feeling that way until the next morning, when Ann and I got into an argument about something that wasn’t in the least important. A few nights later, at an amusingly overpriced restaurant in Tribeca, I told Ann, for the first time, that I loved her. By the time we got home we were screaming at each other. In bed that night, our bickering continued. Finally, I threw the sheets aside, fled my apartment, and wandered New York for hours in the rain. By the time I returned home the next morning, Ann was in the middle of writing the thoughtful, decent letter she wanted me to find after she’d gone. That afternoon, I typed out an agonized email to Bill about what had happened. He wrote back: “sorry about ann and thee.” I realized, then, that I’d overstepped with him. Had been, all this time, overstepping.

Ann, being Ann, soon wound up dating one of the most famous recording artists on the planet. We didn’t speak for many years, but when I called to ask about her memories of the night we had dinner with William Goldman, she said one thing about Bill had stood out to her above everything else: “I’d never met anyone who seemed so playful but also so sad.”

Pauline Kael once commented on the undercurrent of “callous cruelty” in Goldman’s screenplays, and she’s not wrong.8 “I always kill off my most sympathetic character,” Goldman admitted. “I don’t mean to do it. I just do it.”

The most glaring example of Goldman’s cruelty in The Princess Bride is how he allows Westley, as the Man in Black, to treat Buttercup. In both the novel and the film, the Man in Black refuses to tell Buttercup who he really is, even after she’s been rescued. The third or fourth time you watch the film, you find yourself wondering, Wait, why doesn’t Westley just say, “Hey, guess what? It’s me.” In the novel, Westley’s evasions are abjectly malicious. When Buttercup makes a vow, Westley responds (much like he does in the film), “The vow of a woman? Oh, that is very funny, Highness.” When Buttercup is slow moving, Westley tells her to quicken up, or “you will suffer greatly.” When Buttercup tires of her treatment and announces to the Man in Black she’s “loved more deeply than a killer like you can possibly imagine,” Westley hits her. (In the film Westley merely raises his hand to Buttercup—which is bad enough. Even Reiner, in his director’s commentary, remarks that Westley’s raised fist is “pretty harsh stuff for a fairy tale.”) A page later, Westley’s hands are wrapped around Buttercup’s throat. There’s nothing to internally or externally justify any of this, despite Westley’s later explanation that he had to learn whether Buttercup had remained true to him. All of it speaks to the black-eyed sparkle Kael detected at the core of Goldman’s work.

The Princess Bride and Marathon Man were published only one year apart. The first is a joyfully unserious fairy tale; the other a violent, tense thriller. But as novels they’re not so different. In both, a lost father drives the plot. Both have bittersweet endings, complete with a spasm of revenge. And both feature indelible scenes of torture. In fact, the film’s Westley gets off relatively easy. In the novel, Count Rugen goes so far as to set Westley’s hands on fire. Before starting Westley’s “treatment” on a torture contraption known only as the Machine, Rugen delivers a speech that’s all the more chilling in the film for Christopher Guest’s calm, velvety delivery:

As you know, the concept of the suction pump is centuries old. Well, really, that’s all this is. Except that instead of sucking water, I’m sucking life. I’ve just sucked one year of your life away. I might one day go as high as five, but I really don’t know what that would do to you. So, let’s just start with what we have. What did this do to you? Tell me. And remember, this is for posterity, so be honest—how do you feel?

In the novel, after Rugen’s done his infernal work, we’re told that, because of his “humiliation, and suffering, and frustration, and anger, and anguish so great it was dizzying, Westley cried like a baby.” In the film, Westley simply closes his eyes and begins to weep. Goldman’s cliché-hobbled language in the novel forecloses any emotional impact, but actually seeing Westley cry is remarkable, especially in what is, most basically, a family film. That Goldman builds up Westley only to emotionally and then literally destroy him—even after Westley returns to life, he spends the last third of the movie in a state of quadriplegic incapacitation—is evidence of Goldman’s cruelty, yes, but it also speaks to his unusualness as a writer, especially a writer of Hollywood screenplays. Allowing Westley to cry violates of one of Goldman’s core screenwriting rules: Never make your hero look like a loser.

In Which Lie Did I Tell?, Goldman writes amusingly of his experience with Michael Douglas on the action film The Ghost and the Darkness (1996), an original Goldman script that tells the true story of a pair of man-eating lions that terrorized Kenyan railway workers in 1898. Douglas insisted that his (entirely fictional) American character, Remington, have a tragic backstory, which became, appallingly, his having fought on the side of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Goldman resisted Douglas’s idea for many reasons, but mostly because it made Remington “just another whiny asshole who went to pieces when the gods pissed on him. ‘Oh, you cannot know the depth of my pain’ is what [he] seems to be saying to the audience. Well, if I’m in the audience, what I think is this: Fuck you.” In The Princess Bride, Goldman isn’t thinking or writing like a hardened screenwriter burned by movie-star egos. In showing us his tortured hero quietly, hopelessly weeping, Goldman is trying to tell us something about human existence.

“Life is not fair,” Goldman writes in one of his editorial asides in The Princess Bride, “and it never has been, and it’s never going to be.” In another aside directed at younger readers (“Grownups, skip this paragraph”), Goldman goes on: “There’s death coming up, and you better understand this: some of the wrong people die. Be ready for it.…[T]he reason is this: life is not fair. Forget all the garbage your parents put out. Remember Morgenstern. You’ll be a lot happier.”

Rob Reiner’s Princess Bride ends with Buttercup rescued and our heroes making good their escape. We then return to the film’s framing device, a suburban Illinois bedroom, where Grandfather kisses Grandson on the forehead and begins to take his leave. Before he goes, though, Grandson asks if Grandfather can return tomorrow and read the book again. “As you wish,” Grandfather says. It’s a sweet, dopey, perfectly appropriate ending to the film—but it’s not how the novel-within-the-novel ends.

There, Morgenstern’s heroes gallop off into the night:

From behind them suddenly, closer than they imagined, they could hear the roar of Humperdinck: “Stop them! Cut them off!” They were, admittedly, startled, but there was no reason for worry: they were on the fastest horses in the kingdom, and the lead was already theirs.

However, this was before Inigo’s wound reopened; and Westley relapsed again; and Fezzik took the wrong turn; and Buttercup’s horse threw a shoe. And the night behind them was filled with the crescendoing sound of pursuit….

Goldman tells his readers that they will have to judge for themselves whether the story’s heroes made it to safety. Even if he, personally, thinks they did, Goldman writes, “that doesn’t mean I think they had a happy ending.” Goldman proceeds to predict the ways in which life will fail his beloved characters: Buttercup might get ugly, Fezzik might lose a fight, Inigo might be out-dueled, and Westley might be tormented into madness by the thought of Humperdinck’s relentless pursuit. With that, Goldman returns to his book’s chosen theme: “I really do think that love is the best thing in the world.… But I also have to say, for the umpty-umpth time, that life isn’t fair. It’s just fairer than death, that’s all.”

After my debacle with Ann, I wasn’t in touch with Bill for many months, mostly due to my own embarrassment. That summer I went to Iraq to cover the war, then immediately fell in love with someone who promptly moved in with me, then discovered I’d won a literary prize that necessitated my moving to Rome. It was an unusually heady time, to say the least. Shortly before I left New York for Rome, I emailed Bill to ask if we could see each other. He wrote back:

we’d love to see you but it will have to be after scotland. are you familiar with it? please if you are not take a trip to the highlands.

fucking breathtaking. when we get back chances are we’ll take you to dinner.

be well

bill g

Unfortunately, Bill didn’t get back in time before I left New York for what I did not yet realize was forever. Although, in the years to come, I often thought of Bill, I was never tempted to contact him agaxin, if only because we were no longer in geographical proximity.

In 2015, I heard through a mutual friend that Bill’s daughter Susanna had passed away. (Some of the wrong people die.) I wrote a dozen versions of a condolence letter but never sent it. Who am I kidding? I kept thinking. It’s not like Bill and I are close friends—or even, for that matter, friends. I now realize I should have sent the letter precisely because we weren’t close friends. How tragic—how unbearable—to know that the man who wrote The Princess Bride had to endure the loss of one of the little girls whose spirit and light were central to its creation. Life isn’t fair. It never has been. It never will be. William Goldman is one of the first artists I remember who tried to tell me that. I just wish, in this one way, life had been fairer to him.

On the day Bill’s death was announced in 2018, I sat at my computer for hours, wiping away tears while I read testimonials about the man. I discovered that dozens upon dozens—possibly even hundreds—of people had their own William Goldman stories, in which he dropped everything to meet with them, talk to them, have them to his home, take them out to dinner, offer career advice, critique their unsolicited screenplays. I’d spent more than a decade thinking about my whirlwind friendship with William Goldman, always assuming it had something to do with who I was. Bill, despite being gone, had one more thing to teach me. Our brief friendship had nothing to do with who I was. It had to do with who he was.

1 Or sort of said. I don’t remember exactly what we talked about. I do remember outlines, themes—the general carriage of our conversation. I remember how funny, friendly, and alert he was. But anything I’m putting in quotes here is, at best, a half memory. I can justify those quotes because, when I use them, I’m almost always citing or closely paraphrasing something Goldman said in an interview or included in one of his books. Goldman, over his long career, repeated himself frequently—even shamelessly—often telling the same story or making the same observation while using the same timing and language. So he didn’t say this—but I suspect he said something very much like it.

2 Direct quote. He absolutely said “My dear boy.”

3 Many of Goldman’s novels reviewed poorly in hardcover—some of his New York Times appraisers were legendarily harsh, viz “A reasonably gifted child could read Boys and Girls Together long before he could lift it”—and many of his books didn’t find their audiences until they appeared in paperback. Young men were the most avid buyers of most of Goldman’s fiction. Nowadays, there no casual audience for male-oriented popular literature. Video games stole them away.

4 All the President’s Men is the rare movie that can be said to have shaped American history. The film was released in theaters six months before the 1976 presidential election. Support for the Nixon-pardoning incumbent Gerald Ford, who’d been resurgent in the polls, flatlined. Jimmy Carter went on to win the general election with 50.1 percent of the popular vote.

5 James Goldman went on to win an Academy Award for the screenplay adaptation of his 1966 play, The Lion in Winter, in 1969. The following year, Bill won an Academy Award for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Two brothers winning consecutive Academy Awards, much less in the same field, was an Oscar first. James Goldman died in 1998.

6 Paul Newman had originally been tasked with playing Sundance. When, during preproduction, he was swapped for Butch, and a relatively unknown actor named Robert Redford was cast as Sundance, the screenplay’s title was changed in recognition of Newman’s star power. “I know it’s crazy,” Goldman said later, “but I liked the original title better.”

7 A friend who knew Bill too read this description and said, “This is all wrong. This isn’t how Bill’s apartment was at all.” Maybe—almost certainly—not. But it’s what I remember.

8 That said, Kael’s review of The Princess Bride is idiotic. She faint-praised the movie for its “loose, likable slobbiness” but chided its “Americanese” and “anachronistic tone,” which goes to show how capable Kael was of missing the point when she wanted or needed to. She ended her review with a bizarre digression on the difficulty of reading aloud to children.

Joe Gough is an illustrator whose work has been featured in publications such as The American Prospect, The Baffler, NPR, The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Vox.