Touring the Vault

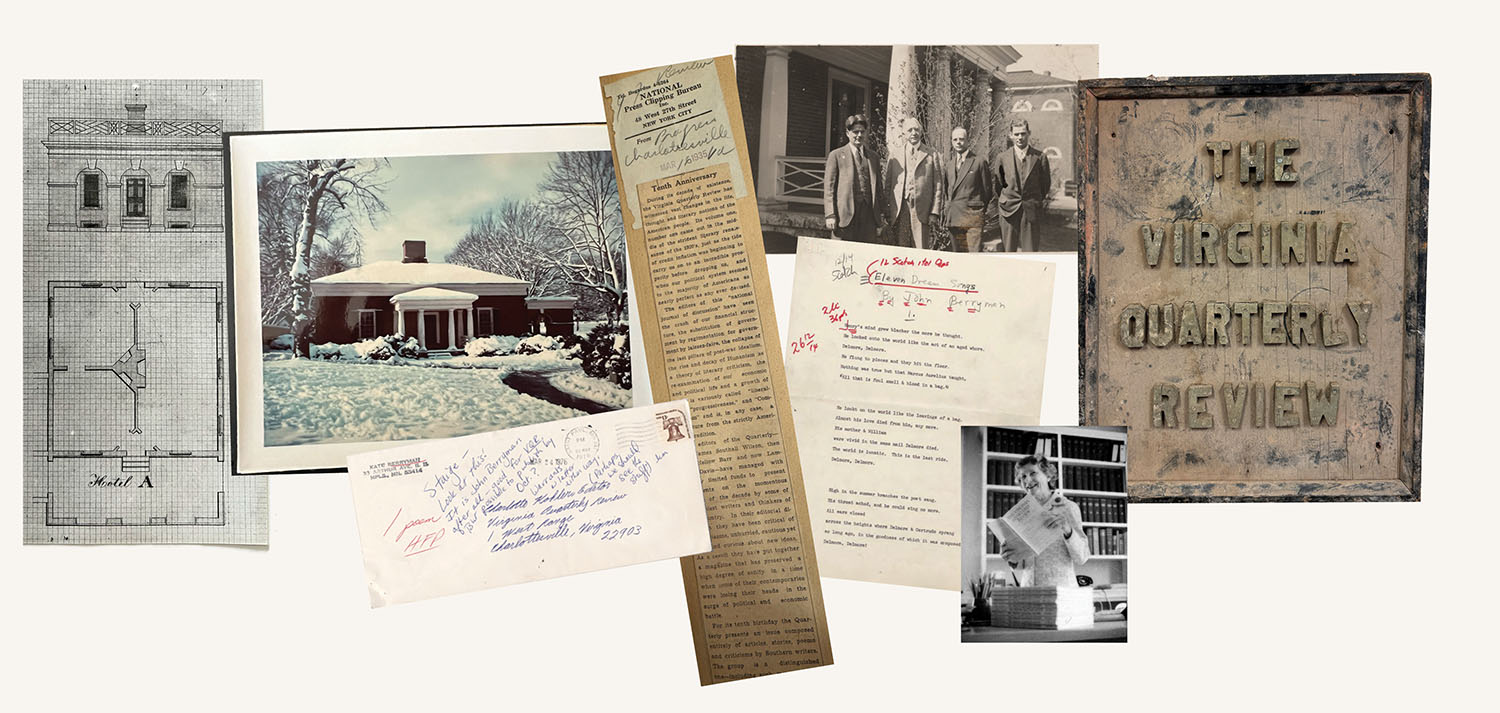

TOP RIGHT: Stringfellow Barr, University of Virginia President Edwin A. Alderman, James Southall Wilson, and Lambert Davis (left to right). Hotel A, One West Range, 1930. (Ralph R. Thompson)

FAR RIGHT: Sign from the first offices of the Virginia Quarterly Review, originally located in Pavilion V, formerly Professor Raleigh Minor’s kitchen.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Charlotte Kohler, 1975. (David M. Skinner)

Since its first issue in 1925, the Virginia Quarterly Review has distinguished itself among literary magazines for its iconoclastic approach to American letters and world affairs. A century later, we’re naturally curious to know what motivated its founders and how they imagined a magazine would complement the mission of Thomas Jefferson’s small but mighty university in the post–World War I era. To find out, VQR’s staff spent roughly 250 hours over eighteen months researching in the archives housed at the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, combing through manuscripts, correspondence, galleys, and other ephemera that brought the early years of that editorial mission into clearer focus.

As early as 1904, when he first became president of the University of Virginia, Edwin A. Alderman set his sights on establishing a magazine “of national scope.” Alderman’s project came closer to reality in 1919, when he convinced UVA English professor James Southall Wilson to edit what was then the Alumni Bulletin, promising to replace it with the more ambitious publication over time. By the spring of 1924, Wilson was ready to step down from the position in order to focus on his biography of Edgar Allan Poe. This gave Alderman the incentive he needed to move forward with founding the Virginia Quarterly Review—on the condition that Wilson remain its editor for the next five years. The first letters soliciting funds to underwrite a journal with “the aim to print articles of general interest to people of thoughtful habits” went out to potential donors in mid-July of that same year.

The inaugural issue of VQR was published in April 1925. Alderman and Wilson selected a dark shade of blue for the cover stock, on which they printed the table of contents. The contents of the first several issues demonstrates that Wilson followed through on the goal he stated in the introduction to the first issue: “to be liberal but reasonable; open to the discussions of all topics and to all stimulating and engaging points of view.” Essay topics included international relations, nationalism in the US, foreign policy, democracy in America, social revolution, and literary analysis. Poetry has been a mainstay since the very beginning, featuring a selection of poets and also Chinese poetry in translation.

Praise quickly followed. The archives contain scrapbooks full of press clippings celebrating the inaugural issue, a “dream finally realized,” as the Roanoke Times put it. In a letter dated December 4, 1926, Richmond-based author James Branch Cabell praised the editors for “producing a magazine which appears quite unworthy of the best literary traditions of the South.” Rather, Cabell wrote, the editors were “producing a magazine which can be read by civilized persons with actual pleasure.”

The very fact of the magazine’s existence eight years later was a “minor miracle.” Assessing VQR upon its tenth anniversary, the Baltimore Evening Sun found it “not merely unburied, but really alive.” Its founding had coincided with the post–World War I Southern Renaissance, but it soon faced economic headwinds with the arrival of the Great Depression. By 1935, VQR had “consistently exhibited courage, honesty, and intelligence.” And it had “commanded the respect of discriminating people not merely in the South, but wherever good writing in English is appreciated.”

Charlottesville’s own Daily Progress marked the young publication’s anniversary by noting that in its first decade, VQR had “seen the crash of our financial structure, the substitution of government by regimentation for government by laissez-faire, the collapse of the last pillars of postwar idealism, the rise and decay of Humanism as a theory of literary criticism, the re-examination of our economic and political life, and a growth of what is variously called ‘liberalism,’ ‘progressiveness,’ and ‘Communism’ and is, in any case, a departure from the strictly American tradition.”

Once Wilson had completed his promised five years of editorship, he returned to teaching and writing full-time. He was followed in quick succession by four editors over the next decade. Wilson recommended part-time managing editor and UVA professor Stringfellow “Winky” Barr (1931–34). The first full-time managing editor, Lambert Davis (1934–38), took over upon Barr’s departure. UVA professor and frequent contributor of poetry Lawrence Lee (1939–40) briefly helmed the masthead, as did Archibald Bolling Shepperson (1941–42). Shepperson had served in the US Army during the First World War; by the end of 1941, the US had entered another global conflict. In August 1942, Shepperson wrote to the VQR Advisory Board to say that his “commission in the Navy has finally come through.” At that point, managing editor Charlotte Kohler served in an unofficial capacity until 1947, when she was named editor.

In the introduction to the twentieth anniversary issue, Kohler wrote, “In a changing world, the Virginia Quarterly has held steadily to its purpose as a journal of independent thought.” And indeed, the first twenty years were foundational for the magazine, establishing its reputation as one of the nation’s foremost literary journals, and home to the work of such luminaries as Fyodor Dostoyevsky, T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, André Gide, Josephine W. Johnson, D. H. Lawrence, Luigi Pirandello, Katherine Anne Porter, Diego Rivera, Eleanor Roosevelt, Vita Sackville-West, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren, among others.

Over these many months, we’ve found inspiration and solidarity in the magazine’s archives as we’ve sought to understand and come to terms with our own past. In the issues that follow, in various forms, we’ll be highlighting what the archives reveal about how this magazine was made across the years, including a feature on our favorite correspondences (although VQR was not “on free sale in South Africa,” Nobel Prize winner and contributor Nadine Gordimer reported in 1951 that she was able to find it in “the smaller and better bookshops” and “always appreciated its excellence”) as well as a profile of the magazine’s longest-serving editor, Charlotte Kohler, who guided VQR from 1942 to 1975. We hope you’ll join us on this archival adventure.

Visit the Special Projects page of our website to see more archival material in honor of VQR’s centennial.