Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

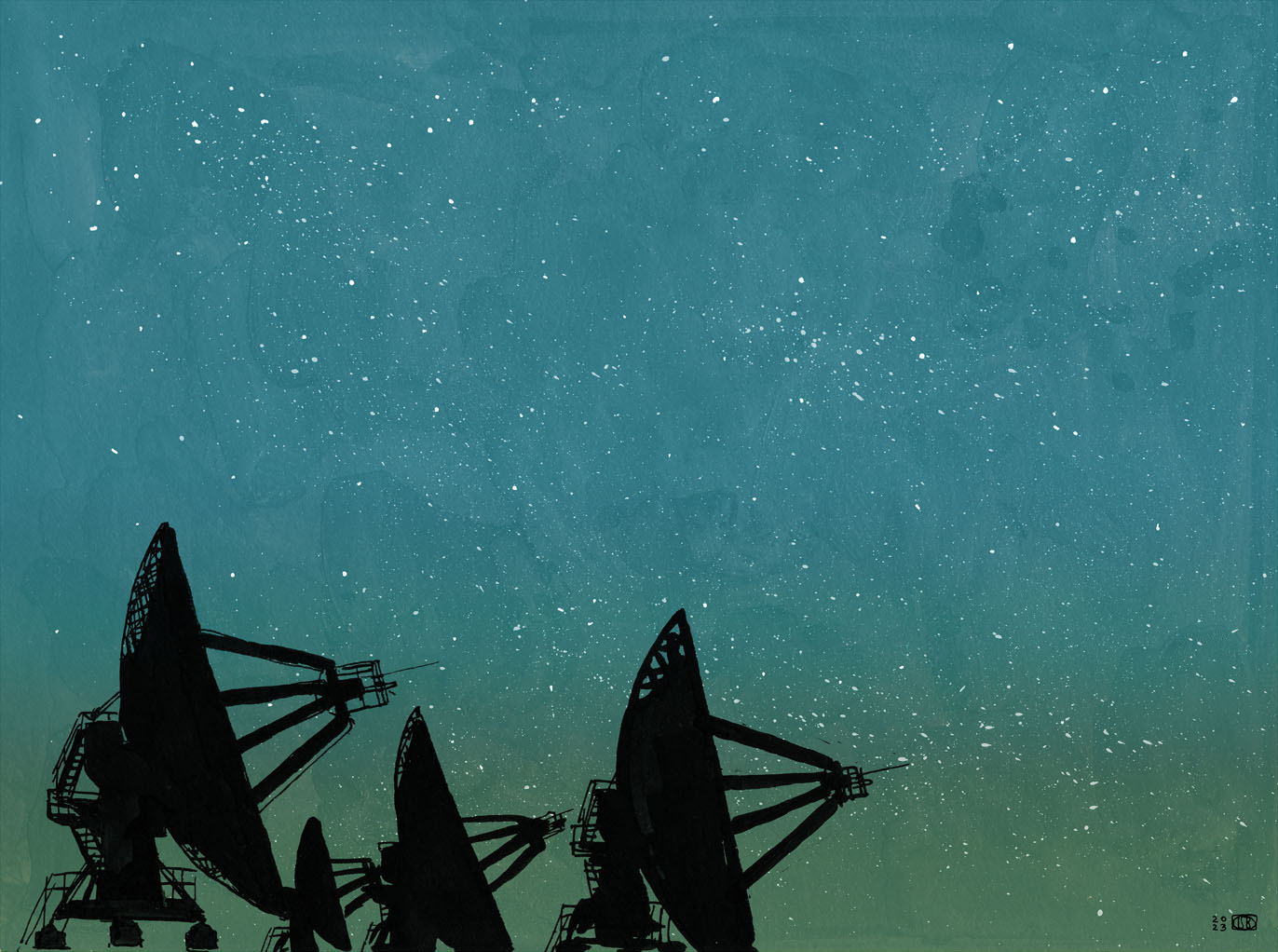

Lauren Simkin Berke is a Brooklyn-based artist, illustrator, and educator whose clients include the New York Times and Smithsonian magazine. Berke teaches in the MFA Illustration program at the Fashion Institute of Technology and in the BFA Illustration programs at Parsons and the School of Visual Arts.