The Vermilion Sea

Uffa had been given the boat for free. It was an unlikely story but true nevertheless. Here was the situation: As a kid, he had made a deal with his friend Aaron that the first person to make a million dollars would buy the other one a boat. The friend had gone on to make tons of money, Berg wasn’t exactly sure how—something to do with finance—and had followed through on his side of the agreement. He bought Uffa a forty-nine-foot French sailboat, fully outfitted for cruising, which Uffa took to Mexico right after Berg’s wedding. He had been down there for a year now, cruising, and making enough to live on by doing telehealth therapy sessions via Starlink. But he was done cruising for the time being, and basically broke, and he wanted to get the boat out of the water. His insurance policy wouldn’t cover the boat, however, unless it was above the hurricane line. So this was the mission that he needed Berg’s help with: to sail the boat from Loreto, north up the Sea of Cortez, to Puerto Peñasco, not far from the border, where he would take the boat out of the water and store it, for cheap, in a boatyard.

On this mission, they would be accompanied by Jakob, a German man Uffa had befriended a couple of years ago in Talinas. Berg had never met Jakob, but apparently he had some sailing experience and Uffa liked him a lot. Berg was a little apprehensive about being on a boat for a week with a person he’d never met, but he trusted Uffa and his sense of people—if Uffa liked someone, Berg almost always did too. Jakob had flown in a few days before Berg, and had been helping work on the boat. He needed to be back in San Francisco by the following Sunday, to return to his job, so their schedule was a little constrained. But with one or two overnight journeys, Uffa thought they’d be able to make it up to Puerto Peñasco just fine.

The afternoon Berg arrived, the sky was all one color, a perfect, pale blue, inviting and calm. Uffa and Jakob were waiting for him when he got through customs in Loreto. Jakob was a tall man, taller than Uffa, which was saying something, and very skinny. He had hairy arms and was wearing bright blue sunglasses, like the kind you might get handed for free at a tech office party. Uffa was tanner than Berg had ever seen him but otherwise looked the same. He had a corduroy fanny pack slung across his chest and was wearing a hat that said only CALIFORNIA in red letters. He gave Berg a hug and then looked down at his phone.

“Gotta go to a marine store and get a new connector for my gas tank,” he said. “Some guy stole mine.”

They took a cab into Loreto and Uffa directed the driver to the main marine-supply store in town, which was called Ferremar. Through the window, the landscape reminded Berg of Nevada or Utah. A ridge of jagged red mountains, cacti and creosote, a few wild donkeys along the side of the road. Loreto was an old town, Uffa explained in the car, the former capital of Baja. He’d spent the last three weeks here and said it was one of his favorite places in Mexico. The boat was actually just south of Loreto, in Puerto Escondido, but there was nothing down there except for one very fancy store in the marina, so they needed to do all their shopping and provisioning up here first.

When they got out of the cab, Jakob said he was going to walk down the street to find a tortillería. Berg and Uffa entered the store by themselves.

“That guy loves the tortillas here,” Uffa said. “I’ve never met someone so passionate about tortillas.”

Inside, one of the clerks tried to help them find the connector Uffa needed, but after several minutes of strained communication in Spanish, it became clear that they didn’t have it. The clerk told them to go to “Anicetos.” They walked back outside, and Jakob was there waiting for them. He had two large bags of tortillas, both flour and corn, and he was eating one of the tortillas, plain.

“Good?” Uffa asked.

“Excellent,” Jakob replied. “Just excellent.”

They tried to look up Anicetos on their phones but found nothing. It was not clear to them if Anicetos was a store or a person. Uffa went back inside and asked the man for directions and he told him Anicetos was about ten blocks away, down Independencia. While he was gone, Berg noticed a hardware store across the street, so they decided to go see if they might have the part. The man in the hardware store looked around for a while and then sighed.

“You’ll have to go to Anicetos,” he told them in Spanish.

It would be a long walk, but there was no other choice, so they headed off for Anicetos. The day was getting hotter, and Berg’s bag was heavy on his shoulders. He was in decent shape, however, from his daily work as a cabinetmaker, so he wasn’t too bothered. Jakob, on the other hand, began to struggle after the first few blocks.

“How much longer?” he said, dragging his feet along the dusty sidewalk.

“Jakob hates walking in the sun,” Uffa said.

“I have no problem with walking,” Jakob clarified. “It is the heat. The heat.”

After about twenty minutes, they arrived at what they believed was Anicetos. It was a trailer on a dirt lot, surrounded by a chain-link fence. Across the side of the trailer, someone had hand-painted the words MOTORES REFFACIONES Y SERVICIO. Below the words was a phone number, which Uffa called. Miraculously, someone picked up and said they would be there in a moment. Jakob walked over to a corner store across the street to sit in the shade, and Uffa and Berg waited near the trailer. Two dogs, one small and one large, barked and glowered at them through the chain-link fence.

Five minutes later, a man pulled up in a station wagon and introduced himself as Aniceto. He was wearing a blue shirt and square-framed glasses, and his hair was silver and neatly combed. Also in the station wagon was his wife and, in the back seat, his four children. The dogs began to bark more loudly now that the family was back. Aniceto’s wife yelled at them to be quiet. From her reprimands, Berg learned that the small dog was named Simba and the larger one named Luna. Aniceto led them inside the trailer, and Uffa explained their predicament to him. Aniceto nodded and then disappeared into the back.

Berg glanced around while they waited. There were various metal sculptures on the front desk of the trailer, a calculator, pens and pencils, a half-drunk bottle of blue Powerade. Off to the side, he saw several cardboard boxes stacked up that said, ELIMINA 99% DE BACTERIAS. Uffa looked over at Berg.

“You heard from Alejandro at all?” he asked.

“A little bit,” Berg said. “I got an email from him a few weeks ago. I need to write him back.”

Alejandro and Rebecca had moved to Spain to retire a couple years ago. Their daughters, Lizzie and Marie, had taken over the property in Talinas, and their sons, Sandy and Hal, who were now in their mid-twenties, lived in Oakland and San Francisco, respectively. Alejandro had become enamored with Spanish architecture and was spending his retirement researching the designs of various Spanish synagogues and churches. He was particularly interested in the Samuel ha-Levi Abulafia synagogue, in Toledo, and had written to Berg about it in extensive detail. He’d also provided updates on Rebecca and their life more generally in Spain. Berg had yet to write him back. He just wasn’t sure what he wanted to say. His life with Oona had been so dark and intense lately.

“I owe him an update too,” Uffa said. “He wanted pictures from the trip.”

Berg nodded and looked over at Aniceto, who was now emerging from the back of the trailer. He had with him a small blue box that was filled with various metal parts and components. From the box, he took out a threaded fitting, and handed it to Uffa, who beamed.

“Aniceto,” he said. “My man.”

The boat was tied up on the far end of the marina, in Puerto Escondido. It was a modern boat, with a self-furling main and electric winches. Berg had sailed it on the Bay, right after Uffa had been gifted it, but he wasn’t super familiar with how it handled. Uffa and Jakob had dealt with all the relevant pre-trip maintenance already, though they had been unable to fix the fridge, which hadn’t been working for two weeks. Uffa said they were going to try to fix it again that afternoon, before they left, but if they couldn’t, they’d just have to pack a bunch of ice. The freezer worked, at least, so certain things could be kept in there. Bottles of water could also be frozen in the freezer and then transferred to the refrigerator to keep things cold.

“Icehouse-style,” Uffa explained.

The plan had been to leave that night, but once they got back to the boat, Uffa said it looked like a Coromuel was blowing in. This was a specific type of wind pattern in Baja, created by the interaction between the cool temperatures of the Pacific and the warm inland temperatures of the sea. The winds could be quite strong, especially the gusts, and it would be a lot to handle, Uffa felt, particularly at night. Berg had no problem with waiting, but Uffa was worried about getting Jakob back in time for work. Together, sitting at the main table in the galley, they talked through the options. After looking at it more closely, Uffa felt they could wait till the following day and still make it back in time—though they would now have to sail two overnights at minimum. He pulled out a set of charts and showed them a version of this plan: Four hundred fifty miles and five days to do it. Berg and Jakob said they thought it seemed fine, so they all agreed to wait until the next day.

They spent the rest of the evening troubleshooting the refrigerator. Periodically, Uffa would have Berg ask ChatGPT questions as he worked on it. The first step was to flush the hoses with vinegar and then try to reconnect everything. Berg had never used ChatGPT in this way and was surprised at how helpful it was. Even so, after hours of tinkering, it became clear to them that there was probably something fundamentally wrong with the condenser. Uffa admitted that they wouldn’t be able to get it working by the time they left the following morning. In all likelihood, he’d have to pay to get someone to fix it in Puerto Peñasco.

“A disappointing development,” he said. “Because I have no money.”

As the sun was going down, they walked over to the only restaurant in the marina for dinner. They ordered margaritas and Berg got shrimp tacos. The restaurant had blue plastic chairs and was filled with gringos, most of them from Southern California, it seemed. Uffa was now even concerned about leaving the next morning given the evolving forecast, which, at that moment, predicted 25-knot winds with gusts up to 35. The swell was looking bad too: four-and-a-half-foot waves every six seconds—a bouncy ride. Berg nodded around at the patio full of sailors.

“Maybe we should ask one of these people,” he said. “I bet there’s a lot of collective local-weather knowledge here.”

Uffa grimaced. “You got to watch it with these old heads down here,” he said. “I try to avoid asking them about shit cause you end up getting mind-dicked for an hour.”

Jakob took a sip of his margarita. Berg noticed he had some sort of Eastern-looking tattoo on the inside of his bicep.

“If we have to wait, we have to wait,” he said. “We have a saying where I am from: Vorsicht ist die Mutter der Porzellankiste. It mean: ‘Caution is the mother of the china box.’”

He smiled at them proudly, waiting for the wisdom of this aphorism to sink in.

“I’m sorry, what does that mean?” Berg asked.

“It means to take slow,” Jakob said, still emanating pride. “Take slow when there is something big and important.”

“I see.”

Over by the bar, a man began to play guitar and sing along with recorded music. Jakob seemed to really like the performance, or maybe he was just getting drunk off of one margarita. Every time the singer finished a song, Jakob whooped and hollered. When he yelled, his Adam’s apple strained against the skin of his neck. Berg knew he was from Leipzig—Uffa had told him this—though he didn’t really know what part of the country that was in. He was definitely a little older than Berg, probably in his early forties, if he had to guess. Jakob stopped clapping and looked back at Uffa, his face red from the whooping.

“I want my kids to learn guitar,” he said. “I want them to have lessons.” Then he sighed and turned to Berg:

“Do you have kids?” he asked.

Berg slept in the aft port cabin and Jakob in the aft starboard one. Uffa slept forward, where he always did, in the V-berth captain’s quarters. Jakob snored loudly all night, an irregular snore that Berg could hear across the engine room. Berg couldn’t fall asleep—it sounded as if they were in the same cabin. He tried calling out Jakob’s name but couldn’t wake him up. He grabbed his phone and googled “how to fall asleep while someone is snoring” but this yielded no convenient tips or tricks. Eventually he resorted to banging on the bulkhead, which would periodically cause Jakob to stop snoring for a few minutes. At some point during one of these lulls, Berg fell asleep.

In the morning, he woke to the sound of Jakob and Uffa talking abovedecks. He joined them up there and Jakob poured him a cup of coffee from a French press.

“Very strong,” he said. “Very strong.”

“How’d you sleep?” Uffa asked. He had his CALIFORNIA hat on backward and zinc sunscreen smeared around his eyes.

“Not so well,” Berg said. Then he turned to Jakob: “Did you hear me calling your name last night?”

“No,” he said, surprised.

“I was trying to see if you could roll over so you would snore less.”

“Oh,” Jakob said, a look of comprehension dawning on his face. “Yes, I’m apneotic.”

“You have sleep apnea?” Uffa said.

“Yes, apnea, yes,” Jakob said.

“We got to get you checked out, man, get you one of those masks.”

“Eh,” Jakob said. “I don’t want.”

Then he looked at Berg: “Sorry you couldn’t sleep.”

Uffa proposed that he sleep in the cabin Jakob had been sleeping in and for Jakob to take the captain’s quarters, that way he was far away from both of them when he slept. Jakob agreed to this. Berg was worried that he may have offended or shamed Jakob about his snoring, but also relieved that the situation seemed to be resolved.

It was seven in the morning, and the weather looked decent enough to depart. The mountains were brown and red and the sky was pale blue again. Uffa took out his iPad and showed Berg the wind app he used. He explained that it was best to use the ECM and HRRR models. Jakob began readying the fishing lines, which they planned to trawl off the back of the boat. He seemed to know a lot about fishing, was talking with Uffa about what kinds of lures would be best for what kinds of fish. Apparently he had gone fishing with his dad a lot as a child in the Baltic Sea.

About an hour later, they were on their way, pulling out of the harbor and heading north. Berg stood up by the forestay, at the front of the boat, looking out for other vessels. Now that they were out of the harbor, the breathtaking beauty of the sea overtook him: birds everywhere, the teal-colored water, giant rocky islands covered in cacti. It was unlike anything he’d seen, an almost otherworldly landscape, simultaneously bountiful and harsh, a true convergence of desert and ocean.

He had been concerned about leaving Oona for a week, but she told him she thought he should go. She was unequivocal about this. It would be good for him to spend a week with Uffa. His therapist, too, had encouraged the trip. She said she thought he hadn’t allowed himself to process what had happened. That he’d been too worried about Oona to metabolize how the loss had affected him. Perhaps spending some time away, in nature, truly disconnected from the world, would help bring him some peace.

Uffa knew, of course, about everything they’d been through. He and Berg had talked immediately after the abortion. They had made the right decision, Uffa assured him, there was no doubt about it. Most children with Canavan did not live past ten, and the years they did live were full of strife and pain. Berg knew what they had done was right, and yet he was still heartbroken. They had tried not to get too excited. They had known, from their genetic panel, that this was a possibility—a 25-percent chance, to be exact. But he had hoped the odds would swing in their favor.

Now they didn’t know what to do. The doctors said Oona should wait at least six months to get pregnant again. And when they did try, what decision would they make? They had avoided IVF the first time around because it would have thrown them into debt—Berg’s shop had its ups and downs but never made much money, and Oona only made an average salary working for an artist residency program. But at this point, after what they’d experienced, perhaps going into debt was worth it. The other option was rolling the dice again, praying that they didn’t hit the 25-percent odds another time. The prospect of that made him feel sick. To go through all of that again? The three months of waiting, the abortion at fourteen weeks, the post-partum depression. It was unfathomable.

He took a deep breath of dry salty air, looked off toward one of the islands. The day was languid and warm, and the sun felt good on his face. He tried to bring his attention to the world around him, to be here, in this extraordinary place, to fully see it.

As he was standing there, he heard someone walking up behind him. It was Jakob, barefoot and wearing shorts, inching along the side of the boat.

“Do you want to come to the cockpit?” he said. “I make some snacks.”

“Oh, great.”

His eyes were blue, like the sea, and his hairline was receding faintly around his temples. He looked at Berg for a moment, looked at him in a studious and caring way, as though he perceived something.

“I’m sorry I kept you awoken,” he said.

“Oh, it’s no problem,” Berg said.

“Maybe you can take a nap this afternoon.”

“I’ll be fine.”

They walked back to the cockpit, where Uffa was eating a slice of quesadilla. On the cockpit table there were several quesadillas stacked on a plate, along with a plastic container of fresh green salsa that they’d bought at the supermarket.

“More tortillas,” Uffa said. “Never enough tortillas for Jakob.”

“Never enough,” Jakob agreed.

They ate the late morning snack and watched the arid mountains drift by. They were going about 6 knots, which was the speed they’d mostly try to make for the entire trip. The diesel engine hummed, but it was not particularly loud. Uffa had his sunglasses on and was looking around at the water, a grin on his face.

“Driving the tractor north,” he said. “Back driving the tractor again.”

The morning wind they were expecting arrived, but hovered around 20 knots, with no dangerous gusts. They shut off the engine, put up sail, and made good progress, buoyed along by a friendly current. Around 1:45, they passed Punta El Púlpito, a giant volcanic rock face, pock-marked with thousands of little crevices, in which many birds had made their home. Off in the distance, they could see a solitary ranch house, bright yellow with a beige roof, alone on the edge of the sea.

The wind had died down by the time they reached El Púlpito, so they were motoring along at 6 knots. As they passed the rock face, which seemed extra alive with bird and animal life, one of their fishing poles began to flex.

“Here we go,” Uffa said.

Uffa told Berg to run below and get his fish knife. Jakob began reeling in the fish, while Uffa killed the engine, unclipped the lifelines, and grabbed the gaff.

“What do we got here?” Uffa said, when Berg came back abovedecks.

“It’s heavy,” Jakob said, straining against the line.

As it got closer, they could see what appeared to be a fin popping out of the water.

“It’s a roosterfish,” Jakob yelled. “Someone film, film, my dad will want to see.”

Berg took out his phone and began filming as Jakob reeled.

“These aren’t good to eat, right?” Uffa asked.

“No,” Jakob said. “Very bad to eat, but prized fish. Very prized. Shit, I think it swallowed the lure.”

“Oh no.”

Uffa reached into the tackle box and pulled out a set of rusty yellow pliers.

“Yeah, it’s got it in its mouth,” Jakob said. “Here, take the reel. Give me the pliers.”

Jakob hopped down onto the lower aft deck so he was almost at water level and began pulling the line toward him. The fish, which they could see clearly now, was quite large, probably thirty pounds or so, with a frilled fin, exactly like—as the name would suggest—a rooster’s comb. It flailed desperately, powerfully, and as Jakob pulled it out of the water, it slapped its body several times against the stern of the boat. Berg stopped filming because it seemed like it was more important to be ready to help.

“You got it,” Uffa called.

“I’m trying.”

Jakob lay the fish on the deck and, as it continued to flail, attempted to remove the hook with the pliers. One pull, two pulls.

“It swallowed the fucking thing,” he grunted.

Blood splattered on the deck, red and watery. Eventually, Jakob managed to wrench the lure out of the fish’s mouth, but by that time, it was exhausted and barely moving. He quickly threw it back into the water, but the fish immediately went belly up, motionless. Blood poured out of its gills and into the water in great sad plumes. The three of them stood there in silence as it drifted away.

Uffa turned on the engine and Jakob crawled back up into the cockpit.

“Why don’t you go down and change,” Uffa told Jakob. There was fish blood all over his shorts.

Then Uffa took a deep breath and shook his head.

“That was absolutely horrible,” he said.

They sat in the cockpit together, mulling over what had just happened. Perhaps they should have scooped up the roosterfish in the net, once it was clear it had died. Berg had taken out one of Uffa’s fishing books and was reading about the roosterfish in more detail. It was bad to eat, the book said, but not inedible. Apparently it was “gamey and greasy,” but some people tolerated it.

In the moment, though, they hadn’t known what to do. Probably the fish had stunned itself by flopping around so much on the deck, Jakob postulated. And yet, there was no way he could have gotten the hook out while it was still in the water—so what could he have done differently?

“At least it will be food for something else,” Uffa said, nodding soberly. He had put on his camo neck gaiter, and he tugged at it with his hand. “That’s one thing I’ve learned being out here,” he said. “Everything gets used.”

They tried to take solace in this, but they still felt guilty. Jakob wanted to see the video Berg had filmed, and the three of them watched it in awe and horror. It was a breathtaking fish, a big-game fisher’s dream, Jakob said.

“People fly across the world to be able to catch that kind of fish,” he told them.

They pulled the lines out of the water for a while. They were all a little rattled, didn’t have the spirit to catch something again soon. They kept motoring and also put the sails back up. There was a gentle 12-knot breeze coming across the beam, and the boat lurched over the swells, propelled by both wind and motor. They passed islands covered in white guano, a small pod of humpback whales, a large tanker huffing along.

As the sun began to go down, all the birds, especially the pelicans, came out to dive for fish, plunging into the water with great joyous splashes. It was still warm out, and the evening breeze was invigorating. Berg took the helm alone for a bit, while Uffa and Jakob went downstairs to cook dinner. They were about three hours from their destination, in Punta Chivato. Soon it would be nighttime, and they would need to navigate by radar.

As he was steering alone, Berg noticed a ripple to starboard. Then, suddenly, a whole bloom of ripples, and he realized he was surrounded by dolphins. Scores of them, perhaps a hundred. They sidled up next to the boat, leaping along in its wake. Berg called down below to Jakob and Uffa, and they ran up abovedecks. The dolphins were on all sides of them now, in front of the bow and behind the stern. The three of them watched as they dove beneath the boat, and shot out of the water, their movements spring-loaded and confident and pure.

The anchorage in Punta Chivato was calm, if not particularly beautiful. When Berg pulled up the anchor the following morning, the chain was covered in a brown muck, which slopped all over the decks. The previous night, Uffa had put up the Starlink and Berg had texted Oona some pictures from the trip so far. He told her about the roosterfish but found it was hard to convey how intense of an experience it had been.

“Is everyone getting along?” she asked.

“Pretty much.”

“Send more pics.”

They were underway by 7:30, heading north again. Today they would sail through the night and make it all the way to Isla Ángel de la Guarda, a large and very remote island. From there, they had one more all-nighter to reach Puerto Peñasco by the morning of the fifth day. Outside Punta Chivato, the cliffs were orange, and pelicans flew low across the sea. After a brief discussion, they put the lines back in the water, and it wasn’t long before they caught a small thresher shark, which Uffa was able to effectively cut loose. He held the shark with a beach towel in one hand, so it didn’t slip, and pulled the hook with the yellow pliers in his other hand. It swam away unharmed.

In the morning and into the afternoon they all drank Jakob’s very strong coffee and talked. Berg learned about Jakob’s dad, who was an American studies professor, focusing on twentieth-century film, and his mom, who worked in advertising. Apparently Uffa had met Jakob’s mom when she came out to visit him in San Francisco.

“Intense lady,” he said.

“My mom,” Jakob said. “Super intense. Super.”

“Intense in what way?” Berg asked.

“Uffa nickname her ‘the dragon.’”

“Like a fire-breathing dragon?” Berg asked.

Jakob thought about this for a second.

“No,” he said. “She is more like Komodo dragon. She bite you and you don’t realize and then, like, seven days later you are dead.”

“I see,” Berg said, laughing.

In the afternoon, they decided to stop in Santa Rosalia for fuel. It was, according to their cruising guidebooks, the last place to stop for fuel before Puerto Peñasco. They probably could have made it all the way without extra fuel, but why risk it, Uffa said. When they pulled up to the fuel dock, however, they were told that there was no fuel in Santa Rosalia, that the fuel dock hadn’t been operational for years. The only option was to bring tanks to a gas station in town, fill up on diesel there, and carry the tanks back to the boat.

It was decided that Berg and Uffa would go ashore while Jakob stayed on the boat. They headed down the pier, toward the town, and it was nice to be alone with Uffa. As they walked, they talked about Jakob. Uffa asked about Oona too. They’d become friends in their own right, which was touching to Berg, and they even texted sometimes. But they hadn’t talked in a little while, Uffa said. Berg told him he thought she was, in general, doing better, though it was hard to say. She had her moments. He did too.

“Of course,” Uffa said. “Of course.”

In town, they had trouble finding the gas station. They stopped in at a corner store and a woman gave them directions: Head across the alleyway behind the store and then take a right. So, the two of them walked toward the alleyway, each carrying a red diesel tank in hand. It was a dirt alleyway, with short barbed-wire fences that cordoned off dirt yards. In the yards, there were chickens and vegetable gardens and even some pigs. The alleyway was lined with palm trees and cacti. Uffa talked about how he wanted to learn all the plants out here, about how much he loved the desert plants.

Then, once they were about halfway down the alleyway, four dogs ran up to the edge of a fence and began barking at them. One of the dogs was a German shepherd mutt, with a particularly ferocious bark and gnashing teeth. Berg wasn’t scared initially: A barbed-wire fence separated them from the dogs. But the German shepherd ran along the fence until it came to a little opening, which it squeezed under and, in an instant, it was right at Berg’s heels, barking and lunging and snapping its teeth. Berg had no idea what to do. Kicking it seemed like it might provoke it more. Running might make it chase him down. So he just walked fast, which was perhaps an insane solution, but it was what he did. After a terrifying minute of being pursued by the dog, a beautiful old woman ran out of her house and yelled at it to come to her. The dog relented. Uffa, who had been following close behind, hustled to catch up with Berg. The two of them scurried off down the road, turned right, and made it to the gas station.

“Holy shit,” Berg said. He was trembling.

“No more alleyways,” Uffa said.

“Yeah, no more alleyways.”

Back at the boat, they recounted to Jakob what had happened with the dog.

“It was one and a half minutes of abject terror,” Uffa said. “Berg handled it well though. That thing was right at his ankles.”

They poured in the diesel with a funnel and then pulled back out of the marina. The wind had died down, so for the rest of the afternoon they mostly motored. The water was glassy, almost molten, that same beautiful teal color as the day before. At one point, they had to pause for about an hour so Uffa could take a therapy call. They killed the engine and just floated there, far offshore, while Uffa met with his client in the captain’s quarters via Zoom. The boat rocked quite a bit in the swell, but apparently, Uffa had told Berg, you never saw that on video. Many of Uffa’s clients knew he was down in Mexico, but they didn’t know exactly where. Berg wondered what this current client would think if they understood that, right now, he was taking their call adrift on the open water.

By the time Uffa’s session was done, at around six, a light wind had picked up—an unlikely wind, coming from the south. Uffa said the wind never came from that direction, but it was perfect, and allowed them to cruise northward gently, the jib full and happy. As night settled, they began to see luminescence in their wake, electric and pool-blue. Around ten, Berg went down to catch a couple hours of sleep. Uffa was taking the first night watch, from 10:30 to 12:30. Berg would take 12:30 to 2:30, and then Jakob would come up from 2:30 to 4:30. After that, it would cycle through again one more time.

When he got down to his bunk, he rummaged around in his backpack for his headphones. Uffa had kept the Starlink out, and Berg wanted to listen to a podcast as he went to bed. He knew he had put the headphones somewhere, but he couldn’t remember where. He hadn’t used them since he’d gotten off the plane in Loreto. He opened the back pocket of his backpack, and to his surprise, found his bracelet from the hospital. “Visitor, Eli Koenigsberg,” it said, with the date Oona had been checked in for the operation. He had no memory of stuffing the bracelet into his backpack, but he must have.

That night, alone on deck, thinking about the baby. Thinking about Oona and how much he loved her. Maybe it would never feel better. Maybe it would just always hurt. He tried to accept that. In the distance, he could make out the spectral glow of Punta San Francisquito. The moon glimmered on the water, a long river of light. Then fog descended and everything became soft and dark and quiet.

In the morning, when he woke to relieve Uffa of his watch, Berg was exhausted. He found Uffa standing up on the helmsman’s seat, looking around. He had both rods in the water.

“It’s so fishy out here,” Uffa said. “I want to catch one.”

They had made it to what was called the Canal de Ballenas. To their right, Isla Ángel de la Guarda had come into view. Uffa seemed to have a lot of energy still. Berg asked him if he’d taken one of his Vyvanses to stay up, but he said no. Gulls and pelicans flew west to east over the water. A panga loaded with crab traps passed them, a blue stripe painted along its planking. Berg took the helm, but Uffa said he didn’t think he needed to go to sleep. They made more coffee, but it wasn’t as good as when Jakob made it. He was still sleeping below, in the captain’s quarters.

After a couple hours, Jakob woke up and joined them in the cockpit. Apparently he’d cut his hand on some barnacles on the side of the boat when he’d jumped in the water back in Puerto Escondido, and he now had the hand wrapped in white tape. It gave him a survivalist look. He shrugged off the injury, said he wasn’t worried about it. They were right alongside the island now, with its washed-out purple and brown and pink mountains. In the distance, too, they could see what was known as Sail Rock, an all-white V-shaped rock covered in guano. It marked the entrance to their anchorage. The rock was surrounded by a large reef, which had to be avoided. The guidebooks suggested you give the rock a wide berth to port and sail through the small channel just to the north.

As they got closer, Berg took in the rock: It was so white, so thoroughly caked in guano, that it looked almost like a glacier or a snowy outcropping. The islands out here felt more wild and isolated than anywhere they’d been. There were no boats, no people, nothing but birds and brown pebble beaches and sprouts of cacti growing out of the rock like little green hands.

The area they were anchoring in was called Puerto Refugio. It was a small cove, protected on almost all sides by a curl of land. They glided in gently and dropped anchor. A family of gulls began screaming at them, a raucous, nonstop vocalization. Off to their left, up on a hill above one of the beaches, Berg noticed some kind of shrine. He couldn’t see what it was, exactly—it was too far away—but it appeared to be made out of stone. He told Uffa they should go check it out tomorrow, before they left for Puerto Peñasco.

“Yeah, we got a little time in the morning,” Uffa said. “We can drop the dinghy.”

They grilled steak they had bought in Loreto and ate it with vinegar rice, a canned-beet and cucumber salad, and a side of tortillas for Jakob. Uffa fell asleep right after the meal, worn out from never taking his second rest break. But Jakob and Berg stayed up abovedecks looking at the stars and drinking seltzer. Jakob told him about his kids, a two-year-old girl and a four-year-old boy. The girl was suddenly, to their surprise and delight, obsessed with punctuation. She loved learning about punctuation and was especially infatuated with exclamation points.

“When we are back home, we will hang out,” Jakob said. “You will meet them.”

“Yeah,” Berg said. “I’d like that.”

Berg felt tired and sun-baked, but, for whatever reason, in that moment he did not experience the pangs of sour envy that he had been feeling every time someone else brought up their children. He grabbed a pillow from the deck, positioned it behind himself, and began to tell Jakob about what had happened. It was dark, and Berg couldn’t see Jakob’s face. Everything about what they’d been through had felt so private. He hadn’t wanted to talk to anyone about it. But now here he was, confiding in this guy he didn’t know all that well.

Jakob told him that he was sorry, and then shared that, before their first two kids, his wife had suffered a miscarriage at seven weeks.

“Not the same thing as what you have had,” he said.

He leaned forward and the light of the cabin illuminated his face. His beard had grown out in the last few days, a faint brown stubble.

“But it is…” he continued. “People do not understand how painful it is.”

He sighed and put his bandaged hand on Berg’s shoulder.

“It is hard to know of it,” he said. “The pain.”

The next morning, they dropped the dinghy in the water and motored over to the beach. They passed an osprey circling a nest it had made on a small craggy island in the water. Periodically, from the dinghy, they saw the shadow of a stingray pass beneath them. And farther away, over by the main boat, the gulls continued their squawking. There were some little chicks around, which, Jakob hypothesized, accounted for the continuous warning calls.

They dragged the dinghy up onto the rocks and began walking around the beach. A few fish skeletons were scattered along the shore, their bones bleached by the desert sun. The skulls had big buck teeth that made them look almost cartoonish. Uffa led them up to a little berm above the beach. From this vantage point, they could see that another boat had arrived that morning, a large three-deck vessel, which was surrounded by a fleet of pangas. Uffa examined it through his binoculars.

“The Tony Reyes,” he said. “Looks like a tourist fishing expedition.”

They continued walking along the berm, through the desert shrubbery and cacti, until they arrived at the shrine Berg had seen from the boat. It was indeed made out of stone, and it had been painted red on the outside and yellow on the interior. There was a small piece of stained glass built into the back of the shrine, which depicted a cross. Below that, a painting of a woman with a crown and a cloak covered in stars. Written above her were the words Benedice este hogar.

Jakob and Uffa looked at the shrine for a couple of minutes and then proceeded onward, down the other side of the hill and back toward the beach. But Berg didn’t follow them. He stayed behind and continued to inspect the shrine. Inside, people had left various things: shells and candles, a copy of the Bible. Berg took the bracelet from his pocket and placed it in the shrine. Then he closed his eyes and prayed for grace, for himself and Oona and everyone else he knew. When he opened his eyes, he turned and saw Uffa and Jakob down on the beach. They were walking into the water, shuffling their feet in the sand, as was recommended, to scare off any stingrays. Berg hurried down the berm to join them.

They left Puerto Refugio that afternoon, motoring out of the cove and past a sea lion rookery. Westerly winds pushed them along for much of the day and into the evening. At night, they kept the same watches. The second night shift was harder than the first—the novelty had worn off, and their sleep debt was setting in too—but the hope of safe harbor in Puerto Peñasco kept them going. Berg dreamed of tacos and margaritas and a shower. Uffa had left on the Starlink so, while Berg was abovedecks, he listened to a playlist Oona had made for him last year.

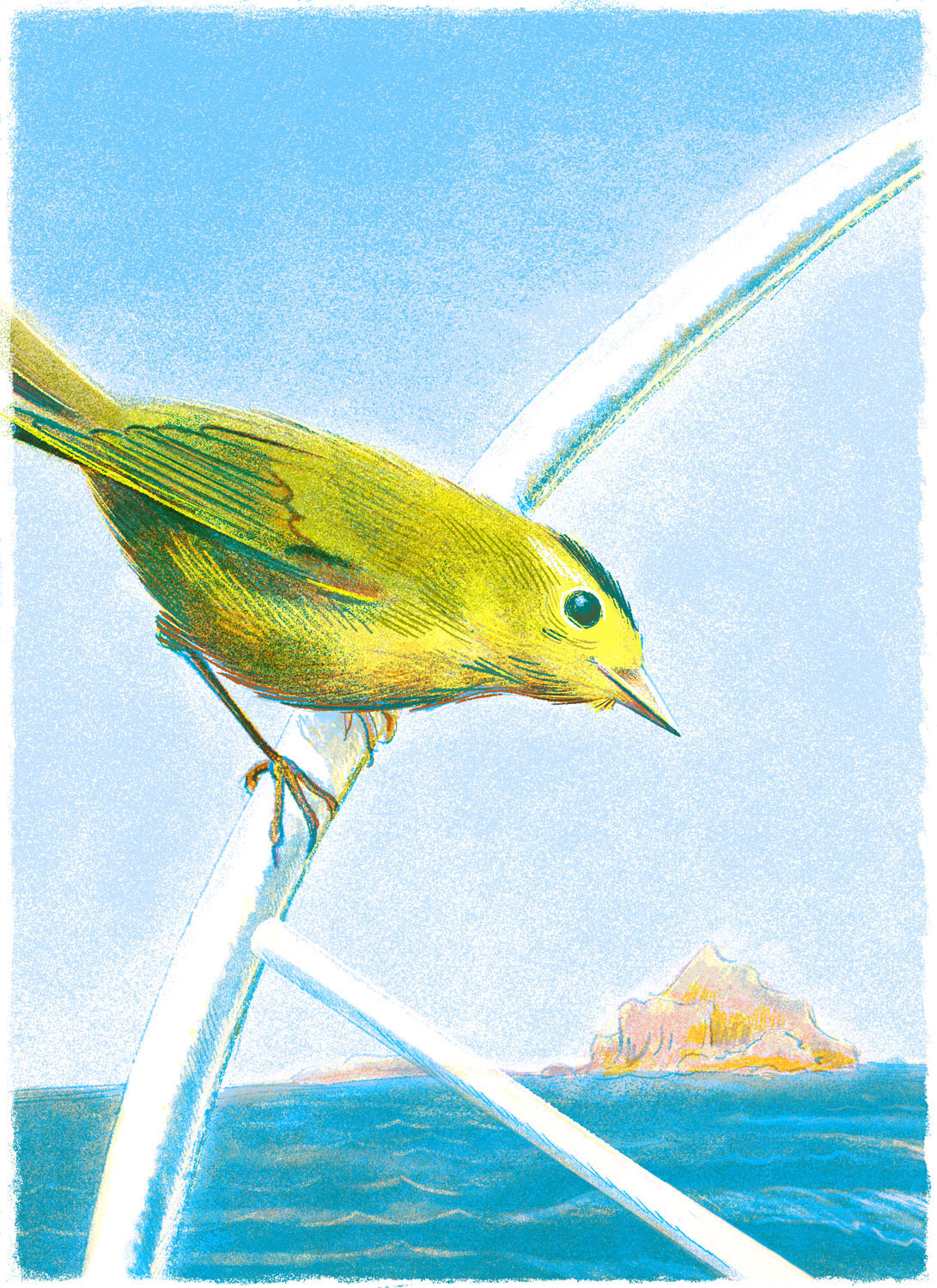

By early morning they were about thirty minutes outside of Puerto Peñasco. All three of them were awake and sitting in the cockpit. As they got closer to shore, a small group of songbirds landed on the boat. At first, one of them shocked Uffa by landing on his shoulder and then flitting away. They were yellow birds, with little black caps. Berg looked them up on his phone and said they appeared to be Wilson’s Warblers. Uffa went below, found some bread, and brought it up in a piece of Tupperware. But none of the birds seemed interested in the bread. Berg read more about them online.

“It sounds like they eat insects,” Berg said.

Uffa looked over at one of the birds to his right. “Oh, okay, dude, eat as many insects as you like,” he said. “I didn’t realize you were keto.”

One of the birds stood on top of the steering wheel, balancing as the autopilot shifted it back and forth. Another settled on the table in the center of the cockpit, right next to Uffa. Slowly, ever so slowly, Uffa reached out his index finger toward the bird. When the finger was close enough, the bird hopped onto it. Uffa then lifted up his finger, gently, and for a few moments held the bird like this. He looked admiringly at it. The bird looked back at him. It seemed happy. It was not afraid at all.

Wesley Allsbrook attended the Rhode Island School of Design. Her work has been recognized by the Art Directors Club, The Society of Publication Designers, the Society of Illustrators, American Illustration, Communication Arts, Sundance Film Festival, Venice Film Festival, Raindance Film Festival, the Television Academy, and the Peabody Awards.