Objects out of the Ashes

On September 2, 2018, a fire tore through the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro. Budget cuts had led to the building’s disrepair, which had led to improper wiring. The fire was brutally thorough: The country’s first and oldest museum lost most of its twenty-million-item collection. Among the damaged relics was Luzia, one of the oldest human skeletons found in the Americas, dated to about 11,500 years ago. The entomology collection, with more than five million specimens, was also destroyed, along with the museum’s storied African collection and two hundred years’ worth of records and artifacts from Brazil’s Indigenous populations. Entire languages were wiped out that day, at least one hundred thirty peoples erased. The whole country was grieving.

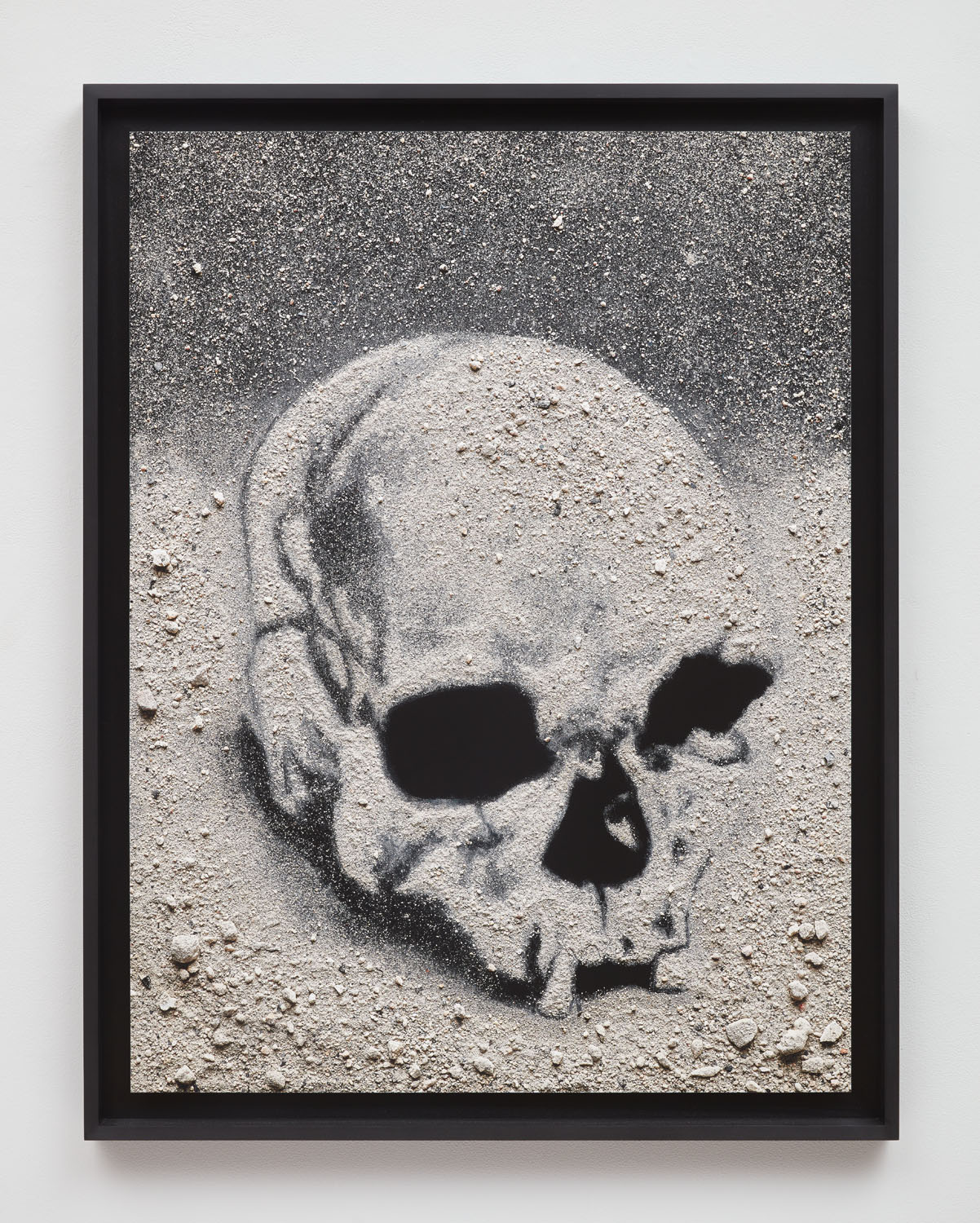

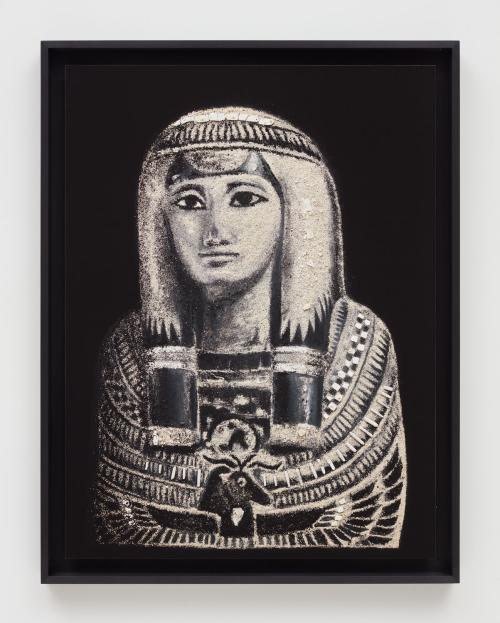

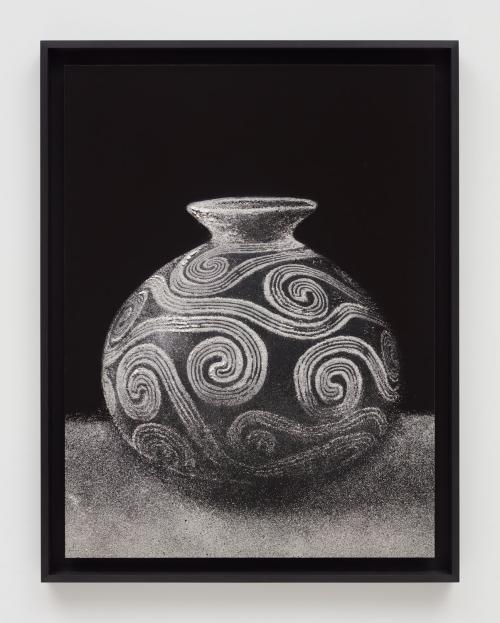

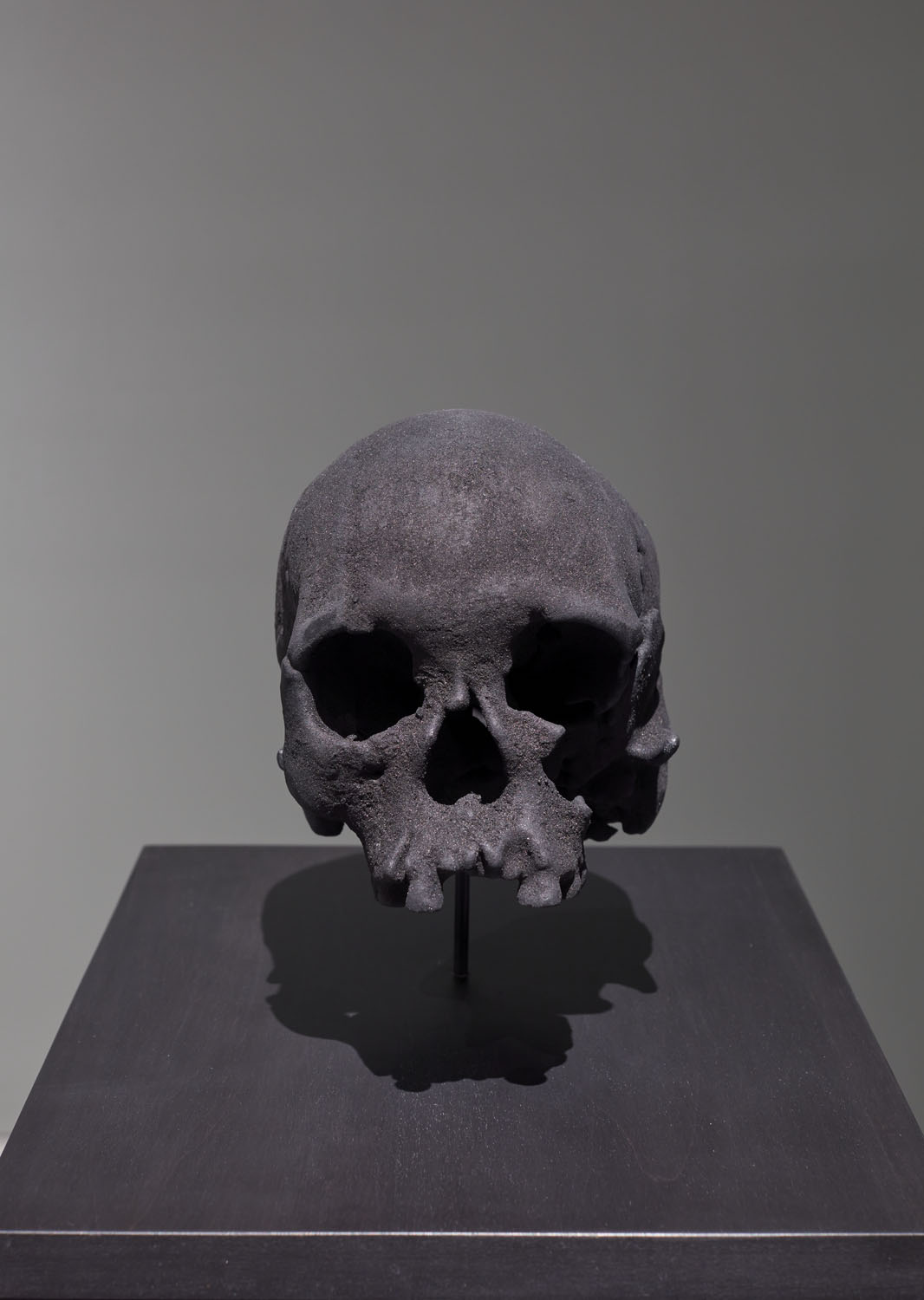

Out of his own grief, Brazilian artist Vik Muniz worked to recreate some of the lost items for a series he titled “Museum of Ashes.” An artist of discarded materials, Muniz rose to prominence with his 2008 portraits of garbage pickers made with trash from the world’s largest landfill in Jardim Gramacho, an hour north of Rio. Ten years later, he turned to a new medium, a different kind of debris in need of a new life. Muniz worked closely with the museum’s archaeologists to research the lost collection, then collaborated with teams from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and Pontifical Catholic University to make replicas of artifacts based on tomographic images taken prior to the fire, using each item’s remains. An Egyptian cat mummy he’d seen in a visit with his son, for example, became an ash-infused 3D-printed duplicate. The museum’s façade was drawn with ash, then digitally photographed and printed with archival ink. New technology and physical objects got to carry the essence of the old.

I was living in Iowa, as far from Brazil as I’d ever been, when I read about the fire. I was devastated, in part because I had never visited the museum. Nor had I been to Rio’s Christ the Redeemer, or to Salvador’s Pelourinho, or to the Amazon. I emigrated from Natal to the US at nineteen for school. Visa restrictions, not enough money, work: One thing or another kept getting in the way of revisiting Brazil. In many ways, the museum’s loss feels familiar to me: I’m always dreaming of finding my way back, of getting caught up with my home country one day, but then something happens (a flood, a landslide, a sudden death), and I realize it’s too late. Another tie is severed. Brazil only gets more distant. Since the fire, I’ve been trying to piece together what the museum might have looked like through the pictures circulating online, and, of course, I’ve repeatedly come up short. My whole adult life, I’ve mostly experienced Brazil through the internet, through virtual tours, mass reproductions, and news reports—secondhand retellings of an original experience I can’t easily access. It is an incomplete picture, but every moment spent scouring fragments of Brazil is one spent reaching for my home, studying it, honoring it. I might never get to have it again, but I continuously walk toward it.

In July 2025, the museum partially reopened with 15 percent of its original collection, redesigned interiors, and a new decolonial curatorial approach. I hope to visit this updated version of it after all this time and all those lost opportunities. Its prized 80-million-year-old Brazilian titanossauro fossil is among the few restored items, now with a double in Muniz’s collection. The Indigenous Marajoara vase from 400–1400 CE was also recovered, with a chip on the rim, now less faithful to itself than Muniz’s meticulous copy.

Of course, reproductions are no replacements for the real thing. For one, their technique “detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition,” as Walter Benjamin argues in his seminal 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” History and lineage are “shatter[ed]” in this process of detachment. But in Muniz’s work, what happens after the detachment is the point. There’s a distance between the historical object and the facsimile. In that distance, there’s great loss. The copy only highlights the irreplaceable nature of the original, and the real thing can never be reached or regained—as such, all reproductions fail. But, in that space where I spend much of my time, there’s also great hope, creation, and possibility. The brand-new object continuously reaches for a version of its past, and so the original lives on. There’s continuity, a new relationship to tradition, new meaning being formed. Where there was once only fragmentation, with Muniz’s ash-infused polymer and ink, there’s proof of mending.

Vik Muniz is an artist and photographer whose works have been exhibited in museums such as the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Museo Nacional del Prado, Tate Modern in London, among others. Waste Land, a documentary about his work...