A Friendship

The metallic desks in the administrative offices of IIT-Delhi, India’s top-ranked engineering college, hadn’t been moved since 1976; nor had their bureaucratic occupants. This created in the office an atmosphere of geopolitical resignation: You were doomed to your neighbors. You were doomed to their odors, their grumblings, their diseases, their distracting asides, their telling trails of powdery dandruff. Some old-timers reacted to this situation by scrunching themselves into sarcophagi of perpetual sneers or pursuing reputations as great bores.

Others went a little mad from convivial rounds of tea—you could see these individuals leaping about the office, jazzed up on caffeine, slapping their neighbors’ tables like monkeys. Of all these neighborly interactions, Mr. Siddiqui felt that his relationship with Mrs. Khanna, who sat at a desk to his left, was by far the most courteous, respectful, sophisticated, moral, intelligent, and mutually beneficial—a model of old-fashioned civility. How else had they gone twenty years without even a smidge of trouble? Why else did they choose to eat lunch together every day?

They had started at the office within a week of each other—him first, her second—a small nick in the chronology of their relationship that, like the fractional age difference of minutes between fraternal twins, was applied with all the more rigor because it felt made-up, a matter of fun, an unnecessary fling with formality: Mrs. Khanna always turned to Mr. Siddiqui for advice from her desk. “You are my senior, after all,” she would joke. He saw her children get married, and she came to the wedding of his older son, and they even met each other’s spouses at college functions. He was often pleased when he thought about her. And a little indignant in the face of imagined gossip. Can’t gents and ladies be friends? he pictured himself telling the naysayers. Arre, what century are you all living in?

Then, one day, Mrs. Khanna was promoted.

“Congratulations,” Siddiqui said from between gritted teeth—it was how he spoke.

“Hai Ram,” she said. “In my fifties they want me to work hard.” She violently swept things off her desk—pens, a sharpener, and a photo frame of the Goddess Lakshmi—into a plastic bag and tied the two ears of the bag in a harsh knot. Then, muttering in that attractive manner of hers, her sparse reddish bun coming loose, she marched to her new office.

Siddiqui, sitting at his desk, his delicate nose twitching, his bald pate shiny, had imagined their lunchtime sessions would continue as before. But instead, as with everything in this office, geography was destiny, and Mrs. Khanna began to eat lunch alone in her new cabin; or worse, outside her cabin with her new neighbor, a tall, big-eared records clerk with a perpetual tilak on his forehead.

Sometimes Siddiqui would glance over at them, and Mrs. Khanna would seem to register him between chews with a tremor of her head. But she betrayed nothing more.

She’s the one who left, he thought. Let her come talk to me first.

On a Thursday, right before lunchtime, Mrs. Khanna stopped by Mr. Siddiqui’s desk. She was wearing a pink kurta with mango patterns stitched all the way up and down. She appeared agitated.

“Siddiqui saab, can we talk for one minute?” Mrs. Khanna asked.

He put one elbow on the metal table and propped his head on it inquisitively. “Tell me, Khanna Madam.”

“So this is the situation,” Mrs. Khanna said in her thick voice, throwing the dupatta over her broad shoulders. “I was sitting and working when a boy entered my cabin. A new student, a fresher. I told him that if he had any questions about fee payment, talk to Akshay. But he said, ‘Madam, you are the in-charge of the personal details, no?’ And then he started saying he wants to change his name.”

Siddiqui had no reaction to this unusual clerical request; rather, he was trying not to act too pleased.

She went on, “I told him my hands are tied. There is nothing I can do about a name. You’ll have to talk to the government. But he’s not listening. He’s saying his name needs to be changed by tomorrow or he will go on a hunger strike. He started out saying ‘Auntie-this, Auntie-that,’ but now he is saying things like ‘See what you can do to me.’”

“What nonsense,” Siddiqui said.

“That’s why I’ve come to you.”

“He’s still there?”

“He won’t move.”

“How dare he threaten you.” He closed his eyes.

“And he’s brought no paperwork.”

“Does he think we are the passport office?” asked Siddiqui, musically clucking his tongue. “For these young people, going on hunger strike is just a fashion. Give me one minute. I’ll come,” he said, making a rose with his hand.

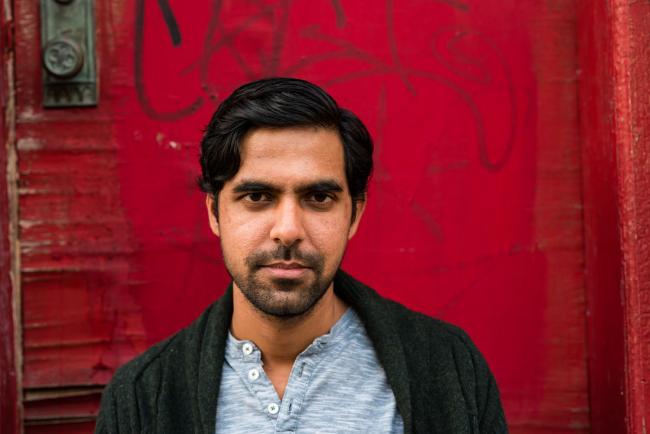

Mrs. Khanna looked grateful. Siddiqui typed out a few useless performative words on his keyboard with his forefinger, then got up and went to Mrs. Khanna’s wooden box of an office. He had never been inside the cabin. The floor was a terrazzo blur that chafed the underside of his old shoes. The desk was a rude, cold, blue-gray gunmetal, the same as the huge almirahs that cast shadows over everyone and everything in the building. The boy was sitting on a plastic chair with his back to the door. He had flaking skin and chapped lips. His hair was curly and long and his stubble was thicker over his lip, making him look pugnacious and young at once. The sleeves of his shirt were rolled up, and he was leaning back comfortably, with one leg over the other in the Western impudent style. He didn’t get up when Siddiqui entered, and so Siddiqui was forced to go around the chair and desk to face him. But Siddiqui didn’t sit down in Khanna’s chair; that would have been too presumptuous.

“Tell me, why are you being rude to Madam?” he asked the boy.

The boy, who was broad, cleaned his nails and looked straight at Siddiqui. “I just want to change my name, sir,” he said, in a hushed, polite voice. “That’s all I said to Ma’am.”

“Your classes are starting tomorrow. You’re an intelligent person; how can this be done in that time?” Siddiqui felt a little foolish speaking the way he did, standing behind the desk while the boy sat—as if the boy, and not him, were the one with the power.

“See, uncle, I did full preparations for this. I put in a request with the government office exactly on time. But there has been a delay on their end.”

“Then come back in two, three days when you have received the forms,” Siddiqui said.

“Uncle, there is one problem,” he said.

“There is no problem,” said Siddiqui.

“Please, one minute, listen to me,” the boy said calmly, but pointedly. “My current name is…my name is Niyaz Alam, and I want to change it to Shakti Ahuja.”

“So you’ll go from Muslim to Hindu?” Siddiqui said, suddenly enraged.

But he was enraged not at the boy but at Mrs. Khanna—and himself. Siddiqui was the only Muslim in the office. Was this the only reason she had approached him? Then why hadn’t she been direct?

There was something else under her stiff, formal attitude—was it hurt?—but he could not see it through his own pain.

The boy shook his head delicately.

“One minute,” Siddiqui said. He went out into the bigger room where Mrs. Khanna was waiting at his desk. But courage failed him. “My sinuses,” he said to her. “Did they just paint your office?” Then he said, “This is a very strange situation.”

“He thinks just like that he can become a Hindu,” Mrs. Khanna said.

“I won’t allow it,” Siddiqui said.

He marched back to talk to the boy. “I have discussed the matter with Madam and it cannot be done,” he said.

“But uncle,” the boy protested. “What I told Madam is—okay, you can’t change my name officially by tomorrow, that’s fine. But all I am asking is that you request the teachers to announce my name as Shakti Ahuja when they take attendance. Because if my fellow students know I am a Muslim tomorrow, then they will know it for the rest of the four years.” He said, “Therefore I am kindly asking”—he joined his hands in the Hindu style—“for your help. In two days, the forms will come and I won’t bother you again.”

“Is it our fault you are delayed?” Siddiqui said. How was it that the boy had not understood that he, Siddiqui, was a fellow Muslim?

“There are always delays in government offices.”

“Then you should have budgeted for it, correct?”

“Sir, forgive me. I am from a small town. I came here using my own resources to change the name. I could not come twice.”

Siddiqui became curious. “What was your rank?”

“Twenty-four,” the boy said.

So that explains his arrogance, thought Siddiqui. Small-town Muslim boy with a big rank. “Why didn’t you think to change your name before?”

“Sir, my abba wouldn’t allow it.”

“Now he has changed his mind because of your rank?” asked Siddiqui.

“No, uncle,” said the boy. “Unfortunately, when I was giving the entrance exam, he passed away.”

“And now you think you can do as you please.”

The boy was unfazed. “Uncle, I promise I’m not insulting any community or religion, but the problems Muslims have in India have increased after Babri and Bombay. People don’t want to give us jobs or rent us houses. I have worked hard to reach here, but my name will always be a weight around my neck.” He confided, “And one more thing: From a young age, I have wished to be prime minister. But you know, sir, even in a secular nation, no one with a Muslim name could ever become the PM.”

“You have not heard of President Zakir Husain? Look at Dr. Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed.”

“But Husain and Ahmed sirs were presidents,” the boy said. “That is just a ceremonial role.”

Siddiqui said, “Don’t you think you are being cowardly? Our community needs the example of boys like you.” He didn’t notice he had said our. Nor, it seemed, had the self-possessed boy.

The boy did that annoying nail-cleaning thing again. “This varies from individual to individual. I have no give-and-take with this so-called community, uncle. It is an old romantic notion. I got into IIT not because of the community but because of myself. Anyway, as you are perhaps aware, the Muslim community has its own problems. People are conservative and backward. And I want to be a free person. This is all I was telling Ma’am.”

Siddiqui was astonished by how much the boy was willing to pander to what he incorrectly assumed was a Hindu audience. “This is a very good speech,” he said, “but this is an office, and in this office we have rules, and the rule says we cannot do anything till you have the papers.”

The boy’s crossed legs tensed. “But I am not leaving.”

Siddiqui said, “That’s okay. You enjoy. At six the office will close. You can sleep here if you like.”

The boy was silent—Siddiqui couldn’t tell if it was defiance or defeat.

Siddiqui found Mrs. Khanna by the noticeboard in the office. “I have tried talking to him, but he is not listening.”

“I thought he would listen to you,” she sighed.

“I’m sorry,” said Siddiqui. Abruptly, he went back to his desk. He was irritated by the boy, by the fact that he had such a high rank, by the fact that he had barely even noticed Siddiqui, by the fact that the boy had made no effort to be persuasive. The boy had just sat there.

At his desk, Siddiqui felt half dead too. He found a piece of paper and kept his head suspended above it like a lamp. His temple ached and his eyes couldn’t focus. He looked down at the small triangular patch of plastic chair between his two legs. He thought, I should eat. But he didn’t get up.

He soon discovered that Mrs. Khanna had galvanized the entire office to solve her case. Within an hour, one of the peons came back with Professor Handa. Handa was a tall man with a long neck and small Gandhi glasses on his thin nose. With his excessively upright posture and sparse silver hair, he looked a little like a plucked pelican. He was wearing a tan safari suit and swaggering about. Khanna followed him into her cabin and Siddiqui could not resist joining them. They stood in the doorway as the professor confidently pulled up the chair from behind the desk and sat himself across from the boy, as if to have an intimate chat. “My name is Professor Handa. Material sciences. Now tell me: Are you okay?”

Handa had a no-nonsense bedside manner which brought the boy to tears.

“Professor-sir,” he said, sniffling. “I have studied hard and got into IIT. All I’m saying is: I don’t want a name to stand between me and my future.”

“But beta, it’s not just a name: It’s your religion, your culture,” Handa said.

The boy said, “But I didn’t choose it.”

Handa looked up at Siddiqui. “You’re a Muslim, right?” he said. “Have you tried talking some sense to this boy?”

Siddiqui was flustered. But he was proud that the professor knew his religion. The boy looked at him with malicious curiosity now.

“Sir, he didn’t listen,” Siddiqui said, finally, in an obsequious manner.

Handa turned to the boy. “Come. Let’s do this. My car is outside. Let us go and drink a cold coffee at Nirula’s.”

“But professor-sir,” the boy stuttered. “This office will close in two hours.”

The professor laughed. “Baap re, I can see why you got a good rank: such determination!” He looked up at Mrs. Khanna. “Have you explained to him that he can be suspended if he doesn’t come with me?” He looked at the boy. “Yes, suspended. Before your first day!”

The boy’s face became pinched, then ugly. He sneered. “Sir, you cannot suspend me. I am the only Muslim in the top fifty. There is an underrepresentation of Muslims at IIT. If you suspend me, I will have no choice but to go to the press.”

“Believe me,” said Handa. “That will not stop me.” Then he started laughing. “Boy has such arrogance! If we don’t suspend him, he’s a Hindu, and if we suspend him, he’s a Muslim!”

The laughter infected Mrs. Khanna. “He even asked me to marry him!”

The boy shrank into himself on the plastic chair, as if unsure how to respond to this mirth. But when Handa said, “Come on,” the boy obeyed.

Siddiqui did not join the laughter.

After this fracas, Mrs. Khanna came by Siddiqui’s desk again. “Sitting very quietly,” she said. “Thank God he has left.” Then she said, “What are you thinking?”

“Nothing,” he said. “Finishing some work.”

“Are you angry about what happened?”

“Why would I be angry?” Siddiqui said, angrily. “Just busy.”

She ignored this. “Actually, what is the way to change the name?”

He said, “You are the register in-charge, Mrs. Khanna. But I’m sure there is an entry in the computer. We can ask Akshay.” But they both hated Akshay; he was a young cocky clerk who acted as if he had attended a prestigious engineering college.

Mrs. Khanna said, “What is funny to me is that he wanted to call himself Shakti Ahuja. Who calls themselves ‘Shakti’ these days?”

Shakti meant “power” and Ahuja was a mercantile Hindu Punjabi name.

“Seems like a normal name to me,” Siddiqui said.

“And did you notice: He looked like he hadn’t slept,” she said. “His eyes were yellow.” Siddiqui hadn’t seen. “I wonder what his parents would think,” Mrs. Khanna went on.

“He said his abba was no more,” said Siddiqui. “He’s doing whatever he wants.”

She said, “Maybe I should have just said yes.”

That was when Siddiqui actually started laughing.

“What’s so funny?” Mrs. Khanna asked, pleased.

“You and saying yes! In twenty years, you’ve never said yes to anyone or anything.”

“Quiet!” she said, smiling.

When she left his side, he sat beaming and then opened his uneaten lunch tiffin and began to eat.

In his mind, he developed a paternal attitude toward the boy. If I could talk to him now, he thought, I’d counsel him to keep his name. I’d say: You’re right about the discrimination. You’re right about everything. But you must never be ashamed of the God you worship.

I don’t believe in God, he imagined the boy saying.

That’s fine, he would retort. But a name contains the culture. It is like a DNA. It has your family’s history written in it. Why would you want to throw that all away? Look at me. I have two sons and a daughter. One is in Dubai. They are all doing fine…

He started thinking about his own life. He was happy with it, thanks to God’s blessings. He had no major complaints, except for the nagging character of his wife, to which he had reconciled himself. Everything had turned out fine. He even had good Hindu friends, such as Mrs. Khanna. In fact, he and Mrs. Khanna should have gone in together to talk to the boy. They should have shown him that discrimination is only in the mind. He began longing for Mrs. Khanna’s company again and got up and went to her cabin.

“Did Professor Handa tell you anything more before he left?” he asked her.

She was staring at her computer. “No,” she said, shaking her head. Then she looked up. “Come sit. Tea?”

He sat. The tea came.

She said, “Would you let Anwar—” Siddiqui’s younger son—”change his name if he asked?”

The idea has really caught her attention, Siddiqui thought. “Of course not,” he said. “Unless there was a very good reason.”

“But what if he was still Muslim, just with a Hindu name?”

“It would only cause confusion. Let’s say he got married. If he married a Hindu girl, she would want to meet his family and would realize he was Muslim. And a nice Muslim girl—why would she marry a Muslim boy with a Hindu name?”

“Also, it is unfair,” Mrs. Khanna said. “Women also face discrimination, isn’t it? But a woman can’t come in and say, ‘I would like to be a man.’”

“Very true,” Siddiqui said piously, though he had wished to make an off-color joke about sex-change operations.

“This is why I think IIT should have Mohammedan quotas,” she said. “It’ll end this headache. If he had been admitted from a quota, then he couldn’t have even thought about changing his name. That’s what I tried telling him.”

“Was his rank really twenty-four?”

They looked it up on a printed sheet. It was. They both had a nauseating feeling that the boy would get his way. The geniuses at IIT always did.

“The students get ruder and ruder every year,” she said. “That’s the problem. If he had come in politely and asked, who knows how I would have reacted?”

“Politeness?” clucked Siddiqui. “Forget it. Just forget it.”

“Part of it is arrogance. The whole society is building up these boys for getting into IIT. And what the boys want is the big salary. When we started—remember?—there were so many idealists who went into the public sector.” She went on: “Now they have become so practical in the matter of their salaries that they want to change their names! Soon they will all take on American names—John, Sally, Harry.” She laughed at her own joke, and Siddiqui joined in. “That is the thing we should have told him,” Mrs. Khanna said, snorting. “Don’t change your name to Shakti Ahuja! Change it to Michael Jackson!”

That night, Siddiqui woke up laughing from a dream he couldn’t fully remember. In it, he had been a young man—he knew that—and he was sitting in the crook of a tall tree with a friend, passing rude comments on the people below.

But when he returned to the office the next day, he felt tired.

He had become one of the men under the tree.

The sound of rustling paper was all around him, and the files smelled riper.

He thought about the boy and his own life. He thought about Mrs. Khanna and her promotion over him. From his desk, he could see her eating lunch with the records clerk once again.

Two weeks later, without informing most people in the office, he retired. The name on his desk was soon replaced by another.

Paul Blow’s work has been published in The New York Times and The Guardian. He has worked for clients such as Nike and Penguin Books.