The Game Is Played With Great Feeling

In the back of an Uber creeping down Decatur Street, my driver, Ursa, this short-haired Black woman a generation above me, is reminiscing about last week’s Frankie Beverly concert, slowing down to repeat the soft consonants of a memory too sweet to keep quiet. “Just as good as ever,” she says. “Just…as good…as ever.” So, despite the years between us and my path toward the North American International Pokémon Championships (NAIC for short), it was safe to assume that the bass line from “Before I Let Go” would follow me into the tournament. It would put me in the mood of a shared sonic lexicon as I peeled open the broader world of pocket monsters spawned by Satoshi Tajiri’s bug-collection-turned-video-game, 1 which had drifted, with a little help from Nintendo and the Japanese government, over to the US back in the ’90s, forever upscaling the ambitions of “E for Everyone” entertainment.

1 Contrary to popular belief, the Pokémon card game and anime emerged well after the Nintendo Game Boy games—Pokémon Red, Pokémon Green, and Pokémon Blue—which dropped in Japan in 1996, landing in the US two years later.

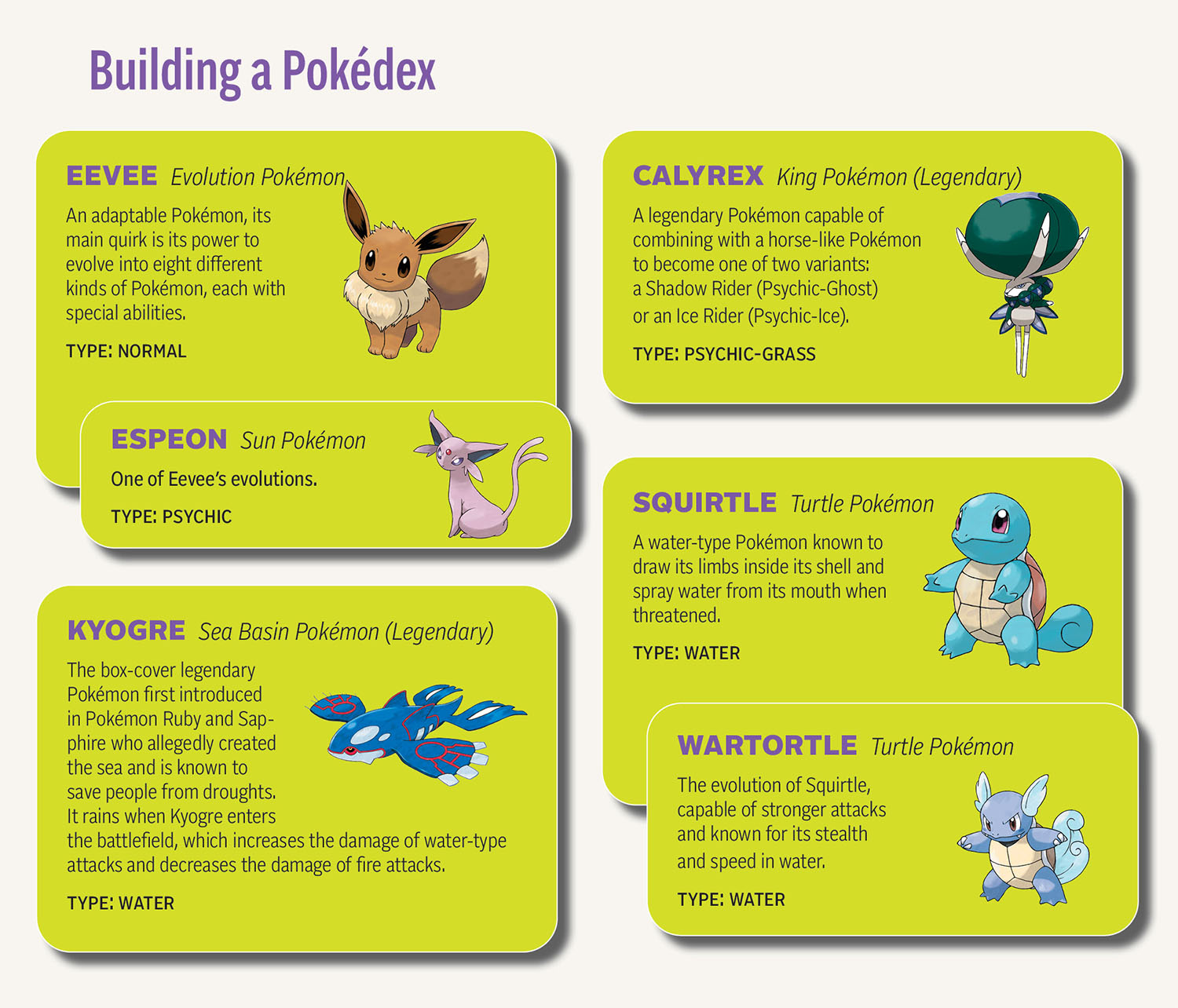

But we were bound for some confusion, Ursa and I. She turns the corner and observes, with some surprise, the crowd of people in fly cosplay outfits streaming in and out and all around the Ernest C. Morial Convention Center: Two little boys dressed as Squirtle and Wartortle, a tall white woman in Misty’s denim coochie cutters and suspenders, a Black-man Brock with his broccoli-green vest, and a woman in a one-piece Eevee costume, collar fluffy as a mink, like one I’d seen this waiter wearing at the Clermont Lounge a couple years ago. No longer the fringe performances they were in the ’90s or even early 2000s, these cosplay fits are popular enough that any normie can find lesser versions of them at Target or Walmart as a last-minute Halloween pick. Such objects are the cultural materials of the present, a superstructural enterprise that keeps on giving, even as it exhausts our collective time and patience; and yet there are more of us than ever, waiting for the next game or trading-card set to activate us, the sleeper agents of Pokémon fandom, many of whom happen to be here at the largest international Pokémon championship in history. Only some of us are players, but most all of us are fans.

Ask your kids, or some nerd born in the ’80s, about a Pikachu and slip into a twenty-minute explainer suffused with a network of interlocking songs, toys, anime, games, plushies, and manga, each of which makes no sense on its own.

“Isn’t Pikachu a squirrel?” my kid asked me recently. “Ain’t he?”

“I think he’s a rat,” I corrected him.

“Electric-mouse-type Pokémon,” my daughter clarified. “Skwovet is a squirrel.”

The semiotic density that these figures have accumulated since their absorption into mainstream culture is hard to overstate: An eight-foot-tall Pikachu poses for photos with strangers on a Tuesday in Oaxaca’s zocalo, dodges riot police in Turkish protest footage, and is the fulcrum to one of Vince Staples’s best bars (“Death row till they put you in the Pikachu to fry”). They’ve blended into rap music and contemporary literature to the point of inseparability, such that, without them, there is no full accounting of today’s tomorrow.

I can see Ursa trying to get a handle on the scene and the meaning of all this traffic. “What’s going on over here?” she asks, a little bewildered. And here’s my chance, perhaps, to tell the tale of Pokémon to someone far outside the presumed Pokéknowledge fanbase. But when I attempt a straightforward explanation, her eyes glaze over; even I have to pause to stifle a yawn. So instead, I say, “You know how niggas be doing All White parties and stuff? It’s kind of like that.”

“Oooh,” she says, laughing. “You have fun, baby. I’m so proud of you.” And with that I say thank you, hopping out of the car and double-checking to be sure I have my Nintendo Switch in hand.

What is it in this gaming community that inspires such obsession, such comfort, such willingness among Black nerds in particular to venture outdoors as we are told in every way, and by everyone, not to? I guess there’s only so much basketball a body can take anyway.

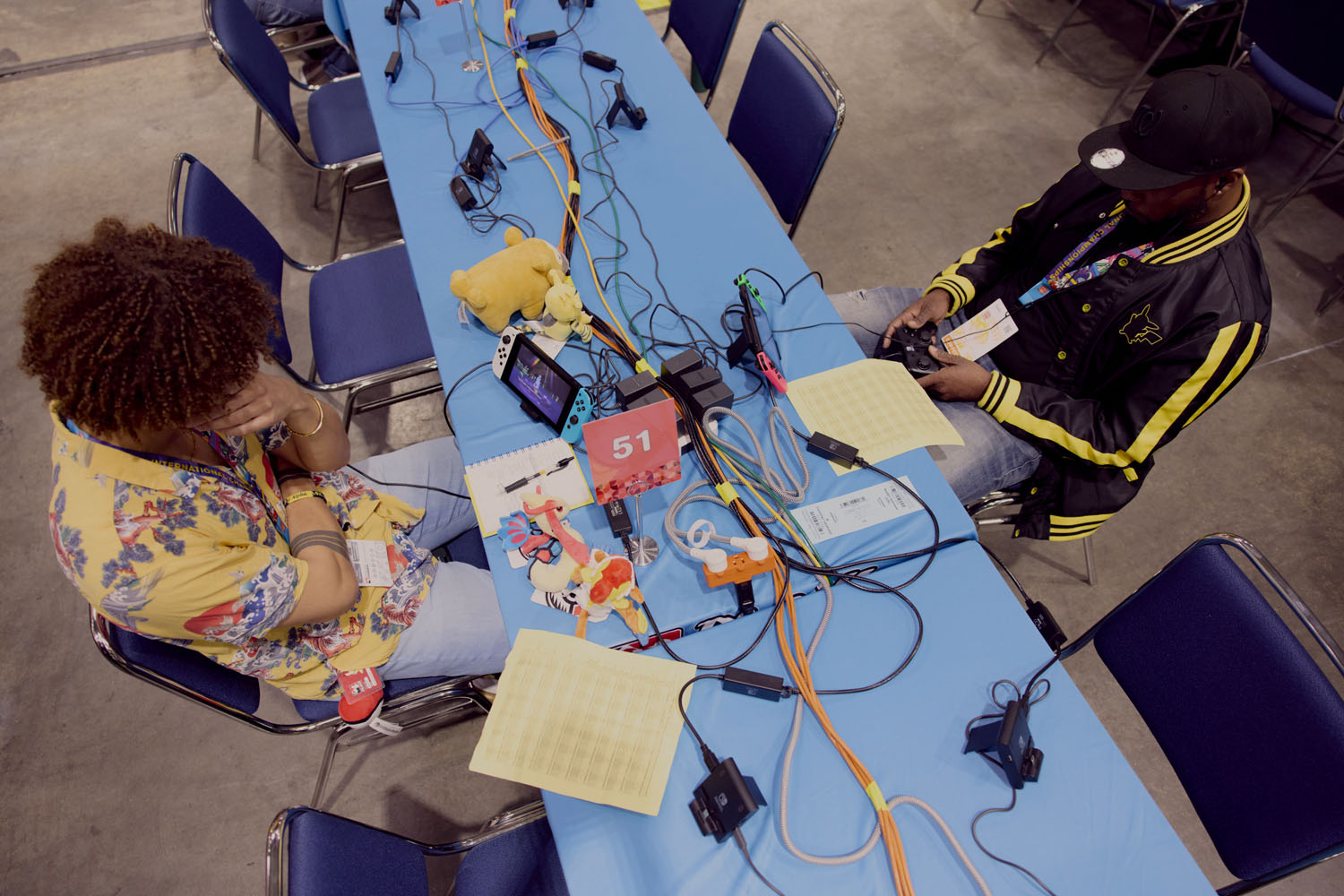

Outside, it’s a late-stage climate change summer in New Orleans, which can only be described as that “run girl, I’m tryna get ya body wet” weather I’ve come to love too much; two Black boys lie upon each other in a patch of grass, refreshing a single cell phone screen with tournament pairings. Inside the convention center, it’s damn near chilly, despite the body heat of thousands of people across four tournaments, rushing toward plushies for sale in one area, examining rare cards in another, high-fiving, hugging, flirting, fist-bumping, dapping up, and passing down the merriment of “good luck” even though many of them will play against each other. In one section, there are long red tables for the largest contingent here, folks playing the Pokémon Trading Card Game (TCG); in another, you’ve got Pokémon Go!, the augmented-reality mobile game that everybody and their mom was playing in 2016; and then there’s the latest in the mainline series this season, Pokémon Scarlet and Violet, on Nintendo Switch, which I’ll be playing. Each Pokémon video-game championship (VGC) battle is played with two Pokémon on each side of the field and two more Pokémon on each player’s bench who can switch in and out. The first player to knock out all four of the other player’s Pokémon wins (though there are other win conditions too). Some spectators have already laid claim to the best small-scale auditorium seating in front of three giant screens, across from three stages where matches and commentary will be live streamed on YouTube. It’s also Pride Week, conveniently. I’m texting friends about their teams and tonight’s plans, fighting off the anxiety that I may have locked-in the wrong six Pokémon. In VGC, you have six pocket monsters per team, and you bring four into battle; you can’t change them during the tournament, so each monster’s abilities (you hope) will complement the others’ and provide a usable strategy against the most common ops from start to finish. And if they don’t, your only option is to adjust your game, i.e., “play better.”

As it happens, six of us have gathered here too: Annie, a photographer living in New Orleans; my girlfriend, Carina, a writer who despises all pop culture outside of music, but who has accompanied me here because, well, Pride Week in New Orleans; and three main VGC player-friendships to watch: Sonnie, Becca, and KaSun, whose collective affability would guide this tournament’s mood. But the broader task has always been this: to form a compendium of attention to regular Black folks outside of pure neoliberal incorporation, all the sophistic marketplace savvy disguised as radical hope or what have you, the constant reincarnation of respectability politics as the only aesthetic aspiration, the perfect victim-to-manuscript pipeline, or the nobler-than-thou discourse of American politics generally, which has culminated in the rise of the negro superhero swinging, flying, or (more likely) drunk off the kind of buying power that vaults us over the malnourished masses of multicultural derelicts damned to desperation in Darfur or Gaza or Venezuela or the permanent ghettos right down the street from every other form of comfort; all this as entertainment conglomerates eradicate sadness through the almighty power of Dolby Atmos while we choke on microplastic popcorn watching yet another Marvel movie, clapping for more.

I’m curious about the lives of diffracted Black folks I’ve met in passing or through play, who will never be famous, nor rich, nor recognized as change agents or activists, educators or writers, scholars or purveyors of a future in which we honor their deeds—in other words, most of us. I want to know what Becca and Sonnie and KaSun and them want but cannot access, and why their desire is scripted through this relationship to a Japanese media-mix object instead of the Church or music or, worse, the bare minimum normative futures of a politician who looks like us, leaving such little room to alter or even articulate the thing we call reality.

And so we play Pokémon, through the refusals of most everything else.

2 Such that if I had to describe it with a poem, it’d be Ross Gay’s “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude.” Why not “bellow forth the tubas and sousaphones”?

Between halls F and J, and just past the all-black Allied Universal security force you might recognize from any Mint Mobile, Dollar Tree, or Beauty Time Supply, a second line surges down the red carpet as part of NAIC’s opening fanfare. Judges, players, streamer-celebrities, and spectators two-step to the brass, and I almost get hit in the face by a tuba.2 Players jog around giant inflatable Pikachus and jump over children chalking their favorite Pokémon in the play area just to get closer to the sound. They speed-walk between the arcade and the player’s stage to catch up, drop their retro Nintendo 64 controllers, and raise their phones like they’re front stage on the last day of a music festival.

3 The oft-noted classic opening to the original Pokémon television show, colloquially known as “Gotta Catch ’Em All,” (written by John Siegler and John Loeffler and performed by Jason Paige), is a mantra that never stops ringing in one’s head, from the first time you hear it at the tender, absorptive stage of adolescence.

Maybe the grandeur of a convention hall dedicated to a children’s fantasy game, where grown folks are trying to be the very best like no one ever was,3 provides an odd sense of what it means to be a competitive creature in the global market; certainly our bodies are responding to a world otherwise intolerant of desire, let alone anything like true feeling. This was the central question back when I started writing about Pokémon after so many years of just playing—though as I continue to play, I sometimes forget I’m working or realize I should be working and forget to play, which might be the point. What is it in this gaming community that inspires such obsession, such comfort, such willingness among Black nerds in particular to venture outdoors as we are told in every way, and by everyone, not to? I guess there’s only so much basketball a body can take anyway.

It’s also nice that New Orleans is, much like Outkast’s Aquemini, another Black experience. I bumped into this dude at Louis Armstrong Park who looked like Wayne in his Carter III era; we were both quacking back at the ducks, and he offered me weed as we watched them play (“Nah, I’m good,” I said reflexively.) We compared the qualities of cuteness between turtles and geese—which, in miniature, we agreed, are their own kind of Pokémon. Then we talked about Jordans for twenty-four minutes, as we both had on crisp thirteens in opposing color schemes. On the street, this woman with a friend who looks like my daughter’s mom stared me dead in the face as we passed each other, took off her headphones playing what sounded like GloRilla, looked me up and down and said, “Mm-hmmm,” and my new friend with the wrong color thirteens on watched her walk away and said the same thing. That’s how it felt to be in New Orleans, mixed-up, of course, with memories of Kanye’s post-Katrina George Bush beef, and Sarah Broom’s hundred-year inscription against dilapidation in The Yellow House, and even my last visit, during the New Orleans Poetry Festival, where I predictably fell in love with a poet and roamed the streets bedecked in Mardi Gras beads behind (or in front of?) a handful of friends from VONA and had forgotten that other forms of joy even existed. All of which is to say that sure, I’m working this Pokémon tournament, but it’s also easy to recall the comment that Arthur Jafa once made about how twerking is its own form of Black virtuosity, be it at Magic City or elsewhere; we all make sacrifices for our art, for the greater good and all that.

Annie, with more glee than they’d been expecting to process on this assignment, asks me why there are so many queer and trans kids here. I recognize a lot of them from tournaments in Louisville or Sacramento, Milwaukee or Toronto, and if I had to call it, I would say that the general openness of the game—compared, of course, to the fighting or first-person shooter circuits’ sports-bro-adjacent culture—allows for a little levity in the field of de facto male supremacy and unqualified aggression. The range of acceptable, or even valorized gender performances is wider than in mainstream culture. That clichéd figure of antisocial white boys doesn’t hold at these tournaments as well as it does on the internet or in the White House; in fact, most of the hospitable interactions I’ve had with white people in the past three years have been at Pokémon tournaments, which isn’t to gloss over what we might call the troubling exceptions of the obvious. On another register, Ofomezie Emelle tells me later on that, compared to Super Smash Bros. players, the gender and race relations with Pokémon players might as well be flipped. In Pokémon, there is no blood, no guts. The threshold for entry is low, and the skill required for mastery is much higher than non-players tend to think; you can train for optimization, then battle and compete, or you can fuck around and hunt shinies, those rare variant creatures who sparkle in the corners of the Pokémon game’s dark caves and hide behind its trademark tall grass.

NFL running back Jamaal Williams (Packers, Lions, Saints) calls shiny hunting his favorite pastime. Between games, on the NAIC stream, rocking an Eevee snapback and Pokémon-emblazoned polo, he preaches the gospel of Espeon: “She’s the bad girl—a city girl,” he says, blending Pokédiscourse with the general anime lexicon by saying that, if he were an anime character, he’d be a villain, no, actually more of a “Hisoka/Stain type,” relishing the moral gray areas called for in any confrontation with power. Williams has come to the tournament with his daughter. For a lot of us, it’s a family thing. So long as you don’t google anything about “sex” and “water Pokémon” in the same phrase (horniness remains undefeated), it’s easy to see how Nintendo is capitalizing on wholesome sportsmanship; and it’s hard to find a safer experience in the video-game landscape that also offers you the opportunity to think in increasingly complex patterns while playing alongside a wide range of, let’s say, constituents. You don’t even kill Pokémon in battle, my seven-year-old reminds me—they merely “faint.”

Comparing the video game to the playing cards, Becca prefers the freedom of the former. With playing-card games, she says, you’re constantly watching your opponent, which is intensified by the fact of her own femininity surrounded by boys and men. You might hear more conventionally attractive women referred to as unicorns in hardcore nerd spaces, though not nearly with the frequency of ten or fifteen years ago. Competing on the Nintendo Switch, your focus is on the console, despite sitting across from your opponent; being together but apart disperses much of the unwanted attention while leaving room to explore shared desire, should it arise. This is, of course, a way that video games work in general, by having you habituate to two different worlds at once, where the suspension of disbelief is amplified by play rather than just narrative. You might speak to your opponent, you might not; you might become friends, you might not. Who knows, you might even find that love in a hopeless place like Rihanna was going on about.

Glossary

Type: A category which determines the abilities, weaknesses, and movement of a Pokémon. For example, a fire-type Pokémon won’t be as effective against a water type. Players will choose Pokémon of a certain type to create advantages in battle.

Shinies: Pokémon with unique coloration compared to their species. While these Pokémon offer no extra benefit in battle, they’re popular collectables.

Poké Balls: Spherical devices used to catch wild Pokémon.

Legendary Pokémon: Very rare and powerful Pokémon. In some restrictive competitions, only one legendary Pokémon may be used in a match.

Evolution: Given certain conditions, such as leveling up or being exposed to a particular item, a Pokémon will transform into a new and usually more powerful species.

I first met Becca and her cousin, José, playing in a local Pokémon tournament at Rutgers, where, it turns out, she was just getting started with the game. It’s always a roll of the dice when one encounters Latin Blacks like them in the wild, whether they will affiliate with or disavow that weird racial mechanism which guides so much social interaction in one way or another. But with Becca and José, it was easy to tell by what they offered through eye contact and gestures, the way one notices another’s presence apart from but equal to their own, which doesn’t happen nearly enough across racial lines.

4 Each Pokémon can hold a single item, which is a big part of the game’s strategy. These items do many things, such as heal damage, increase attack, or add speed. In this case, Choice Scarf doubles the speed of the Pokémon carrying it.

And here in New Orleans, sans José, Becca sweeps her first two matches running a Choice Scarf Kyogre4 team, the trick of which depends heavily on positioning: If Kyogre goes first, thanks to the 50 percent speed boost from the Choice Scarf, you get to spam some of the strongest spread moves in the game, those attacks that offer an advantage by hitting both of your opponent’s Pokémon at the same time. The problem with Choice items, though, is that they lock you into using the same move even as battle conditions change. It’s too predictable; your opponent can switch Pokémon or counter the repetition if you don’t overwhelm them quickly enough. Becca’s body language says it went over better than she expected.

After her second win, she strolls up to one of the judges, cheesing, and hands over her match slip. “I did it, girl—oh my God!” she says. Becca doesn’t even seem to notice how happy she is herself. There’s a sincerity here that, whenever I see Black folks ensconced in it, provides one of the least complicated forms of pleasure: We provincialize, rather than forget (at least briefly) the circuits of violence producing the game itself.

Seeing Becca this kind of happy reminds me that we will, of course, all die, and we will also injure one another or someone else in the countless microtransactions at our real jobs or elsewhere; but between these bookends, some affirmation of life is also happening. There’s a recognition that I’ve used video games—and especially Pokémon battles—to recharge for the longstanding conflicts that rage on the very moment I put the console down.

Becca is modest, happy just to win more than she loses, but she is objectively good at this game. One might describe her style as patient, contemplative; she doesn’t always ascertain a path to victory as quickly as folks who’ve been playing since birth, but she can recognize that path pretty clearly after the fact, forensically replaying her choices in detail. When we played against each other in New Jersey, I knew I liked her enough to be friends, but didn’t like my chances of winning. (I did, however, beat both her and her cousin that day, and proudly held back my shit-talking as a courtesy.) There are a hundred ways to play the game and even more Pokémon to complicate one’s options. Veteran players tend to understand and even leverage different styles of play against their opponents; you learn what an opponent is capable of based on choices they did or did not make in the past and process this information alongside everything else. Some players map out all the conceivable actions available each turn, whereas others crunch numbers and practice incessantly. Some, like myself, toy with the mathematics behind the game, but prefer intuition. Any player you ask about their team composition, or the choices they make will almost certainly use the word feeling, what felt good to them. Ofomezie describes the development of his own game as making surer choices each turn; rather than trying to read what your opponent has or would do in the vein of poker, you might be better off planning your own play such that you create the best chances for winning in the long-term, hardly determined by your opponent’s actions. A few years ago, a programmer interested in the complexity of the Pokémon video game created an AI that could train and optimize decisions in battle, rapidly evaluating thousands of potential decisions each turn. It still couldn’t beat some of the world’s best players.

5 The compendium of Pokémon lore found both in-game and on Google. You might learn more than you ever wanted to about a Pokémon given enough curiosity.

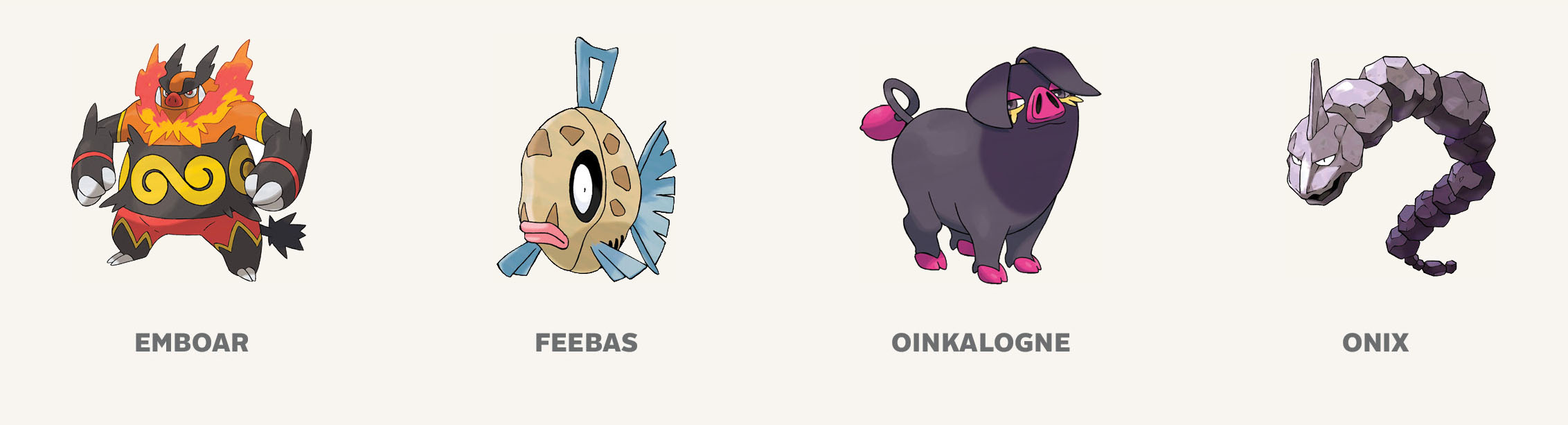

Among the flock of fans and players, spectators and plus-ones gathered here, Sonnie is probably the warmest and often the silliest, a clown—and I mean clown in the way that a lover or your mother or your friend might call you a clown because you’re making them laugh when they don’t want to but maybe need it the most. At the Orlando regionals side event a few months ago, this man Sonnie goofed off with an “all pig” team, sitting across from me with a straight face while the likes of Oinkologne and Emboar damn near destroyed the meager record I’d built up to that point. The nearest comparison to this I can imagine would be recruiting my seven-year-old twins for the Olympic basketball team, and starting them, no less; it’s not that they aren’t cute, but are they Olympic basketball team material? Sonnie’s favorite Pokémon is Milotic, who evolves from this oogly fish named Feebas into a mermaid-like siren whose Pokédex5 entry refers to her as “the most beautiful of all the Pokémon,” and who also “has the power to becalm such emotions as anger and hostility to quell bitter feuding.” Becalm is such an incredible post-glow-up word. Becalm. I’m reminded of the poems in Marlin Jenkins’s Capable Monsters, full of parallelisms between Black queer life and Pokémon more generally. The first poem, “Evolution,” reads…

I was a boy and then

I switched from milk.I was a moth and then

a boy plucked the wings…………………………

I was a monster

and nowI am a monster

stillbut with different teeth.

A few friends and some colleagues scoff at the idea of making a poem or writing an essay “about” Pokémon, even those who play these games for more hours than they read or write, or whose children have shaped their own consciousnesses around the franchise; it seems they would rather decorate ideas from nineteenth-century Western Europe with flecks of ethnic color than stare into the dead eyes of today’s all-animated everything. I suppose this offers a pretense of escape while abdicating responsibility for the present, which we’re all susceptible to. Case in point: Sonnie texts me to say that he’s got an appointment with the Pokémon Center, and asks if I wanna go, to which the answer is obvious.

If the game’s two-on-two battles can be described as chess with hundreds of customizable cartoon pieces, the Pokémon Center is a digital space where you stop and heal your party of six and perhaps purchase potions or Poké Balls or a host of common items to aid in your journey. It’s a clear sign of capital’s ownership over social life that the IRL version of a Pokémon Center is dedicated to shopping, not healing; or worse, healing through shopping, and that you need an appointment to peruse the limited-edition Pokémon merch.

Outside, I chat with the employees, most of them Black, laughing and joking right up to when I start asking them about pay and work conditions, which, as one might expect, few of them are willing to trust sharing with a stranger floating in for the weekend. They exchange knowing looks. Carlotta, a Pokémon Center manager, smiles for a picture. Inside, I buy matching T-shirts for myself and the children, green and blue with Onix or Wailord insignias on their little pockets. Sonnie convinces me to get a black T-shirt with Pikachu on the pocket and some orange Tatsugiri hoochie daddy swim trunks; I send a photo to Carina of the matching, front-tied Tatsugiri top, but she seems uninspired and makes no promises to wear it. Annie, meanwhile, offers up their exclusive merch access by phoning a friend to talk gifts, snatching up bags and shirts and trinkets with the determination of a giver. Sonnie’s mood is funny here too; I thought I was a flirt, but something about the fact that most of the employees were Black women opened up a new category of sociability in both of us where, walking through the winding line, a game of tag through compliments ensues: my crisp and correctly colored thirteens, his gorgeous hair, her earrings, my nose ring, her necklace, them jeans. Sonnie barters for but fails to secure the last backpack on the rack. He smiles nevertheless, walking away all but empty-handed.

As for me, it was important for my pockets that I get the hell out of there.

Becca and I had planned to meet at the main stage for Round 4, where we sit and gossip about things that are, of course, nobody’s business. This dude behind me whom I’d never met a day in my life taps me on the shoulder: “What’s up, other Black people?” Erry is his name, it turns out, and we chat with him for a while, trading jokes and info before turning back to the match: Wolfe Glick vs. Jeudy Azzarelli.

Wolfe Glick is the most famous Pokémon VGC player in the world. Jeudy Azzarelli is also well-known, a great player in his own right, and one of my favorites with regard to affect: a warm and silly cutie with the patience of a saint who, last I saw him, was prancing around a regional tournament in a dashing black-and-white anime maid costume. Both players are fun to watch in that you can’t always understand their choices right away; there’s an excitement in the space between your thinking and theirs, not altogether different from catching up to the layers of meaning in a great turn of phrase. I love watching the expressions of gamers as they play, living in that relay between controller and screen, that subtle portrait of mental activity; the game brings something out in them through their facial expressions and contortions, shares with us a sliver of their inner lives and fierce wants—in this case, to win, which always suggests something more.

Seeing Becca this kind of happy reminds me that we will, of course, all die, and we will also injure one another or someone else in the countless microtransactions at our real jobs or elsewhere; but between these bookends, some affirmation of life is also happening. There’s a recognition that I’ve used video games—and especially Pokémon battles—to recharge for the longstanding conflicts that rage on the very moment I put the console down.

Restricted formats, like the one we’re all playing now, allow each player one overpowered legendary Pokémon in a party of six: Becca’s Kyogre, for example. Wolfe and Jeudy are both using a Pokémon called Calyrex, but in opposite forms. Picture the big-headed telekinetic children in Akira, but friendlier and more deer-like; now imagine that this big-headed telekinetic deer-child is riding one of two horses, dark or light, ghost or ice. Wolfe uses the ghost type, while Jeudy brings the ice. The potential interactions of this pairing could manifest a whole book; suffice it to say that one is naturally fast and fragile, the other slow and thick. Taking into account the records of each player only amplifies the tension: Wolfe has won a ridiculous number of these tournaments, while Jeudy, besides his high-level consistency, finished second at Worlds in 2014.

Jeudy shakes his head and nods and swivels in his chair, considering his choices for this turn and the next. Wolfe goes through all kinds of unconscious gesticulations, touching his goatee, leaning into the screen, then back in his chair with his hands clasped behind his head. Turn-based games are difficult to represent; unlike fighting games, your dexterity is irrelevant. Between Wolfe and Jeudy, the management of information is only partly visible, more like chess than Wii Sports. Put another way: In lieu of Street Fighter’s rapid-fire commands, that classic quarter-circle punch is here almost entirely mental and near silent, save for the applause or gasping of spectators following each knockout or clever switch. After just a few tight minutes, Wolfe takes the set 2-0.

I get up to stretch my legs and find KaSun, my homie who needs only six more points to make it to the world championships in Honolulu. He’s up against Joe Cartin, a player with the same record (5-3) who, like KaSun, needs just one more victory to make it to Worlds. This is their last match—and last chance—of the season.

My man KaSun sweats real buckets playing this little diamond turtle called Terapagos as his team lead, while Joe runs the same ice horse Jeudy did just a few games back. Again, the thicky ice horse takes a loss: KaSun runs through Joe 2-0. KaSun smiles, but only a little, a show of relief and pleasure that also aims to be inoffensive to his opponent. He doesn’t give much away at first glance; he’s careful and quiet, though not at all meek. (Being a Black dude of a certain size restricts your comportment for the sake of others’ comfort—and yes, I’ve sometimes felt an unearned kinship with KaSun in the tall soft-boy-negro-non-NBA-player social category.) When he won a local tournament undefeated and I texted him: I heard you put work in at a challenge today and then strolled off smooth, he replied: did a little something something lol. He reminds me of my friend Erving, who doesn’t curse but says nigga all the time, and with whom I’d lost contact after he moved to Arizona for good when his mother died.

I’m never entirely sure what shape friendships should take. This has become truer as I’ve gotten older. My attempts to befriend other Black men in particular have not always borne fruit, but I’ve pushed through my own insecurities about bothering people, or being too queer for the locker room, or not queer enough for certain sex clubs, and altogether annoyed by how my social class makes friendship with many writers impossible. Perhaps, above it all, there remains a fear that I might have little to offer outside the supplication used for bartering elsewhere, that my energies are split between the constant sentence-making flood in my brain, the four children at home, and the renegotiations of boundary and desperation where my mother and siblings are concerned. These tournaments interest me because they are at the confluence of public ritual and private need, this Venn diagram where loneliness meets a shared occupation outside of one’s job. So, it’s nice here, for what it’s worth.

After the tournament, we go to this rooftop party at Galaxie, where the DJ is a tall brown-skinned woman with a ’fro and anime swimsuit top. There’s a couch by a small, murky pool, a few people dancing next to that, one in a giant strap, and a young Black couple smoking weed on a chaise lounge. Cover cost aside, the whole thing feels a little utopian—to me anyway.

Sprawled on the couch, Annie and Carina talk about how, having known nothing about Pokémon, they left the tournament feeling like they’d wrapped up a 101 course in the game’s mechanics—thanks to Sonnie, especially. He is, to their minds, the embodiment of what we might call warmth these days; Carina suggests that he’s basically a Pokémon himself. The sun is creeping in and out of cloud cover as we sip on these too-bitter cocktails. Everyone at the party knows something about Pokémon, but not everything, and they seem genuinely fascinated by how we spent the day. We ruminate on how memory works, how we might easily recite the original 151 Pokémon in song but rarely recall proper nouns for anything of “substance.” So loss is mingled in with this nostalgia, for the freedom to follow those pleasurable associations of one’s youth, and to hold on to them beyond the responsibilities of aging.

Not for nothing, but after NOLA, Sonnie is off to Japan to teach English. This feels fitting, the reversal of using a Japanese game to bring adults and children together while working his job at a youth center in DC, to teaching English to children in Japan. When he speaks about those kids he’ll be leaving, there’s a reverence and respect that many folks don’t express for their own children. Perhaps the game can help bridge a gap once more, however many thousands of miles away.

Both of us out of the loop and tired, I miss plans to hang out with Becca the next day but assume we’ll meet up in New Jersey. When I ask who her favorite person she’s met through Pokémon is, she recalls her best friend, Brad, whom she met a few years back through the card game; they still play together, casually, exaggerating their affect with each turn like characters in the Yu-Gi-Oh! anime, cracking each other up in the strength of their long-held comfort.

Two months later, KaSun doesn’t exactly catch wreck at Worlds, but there’s no ambiguity as to whether it was worth it. When we chat again, he’s already back on the local scene—practicing, playing; he hasn’t shed any of his enthusiasm. And when I finally get my schedule semi-correct, with a new teaching gig at the college and the children back in school, I hit him up to say I’ll be going to the October regional in Kentucky. “Let’s go!” he writes back, plus a fire emoji.

The tournament falls just before my week with the twins, and their mom asks me if I’ll take an extra day because she’s going out of town. Well, I think, they’re seven now, and one’s a great reader, so there’s no time like the present for that inevitable introduction to the materials.

So, I ask them: “Y’all wanna go to this Pokémon tournament?”

Annie Flanagan is a photographer and journalist who received their MS at the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. In 2023, they were an artist-in-residence at the Skowhegan School of Painting. Their work has been published in TIME magazine, The New York Times, ESPN, and...