Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

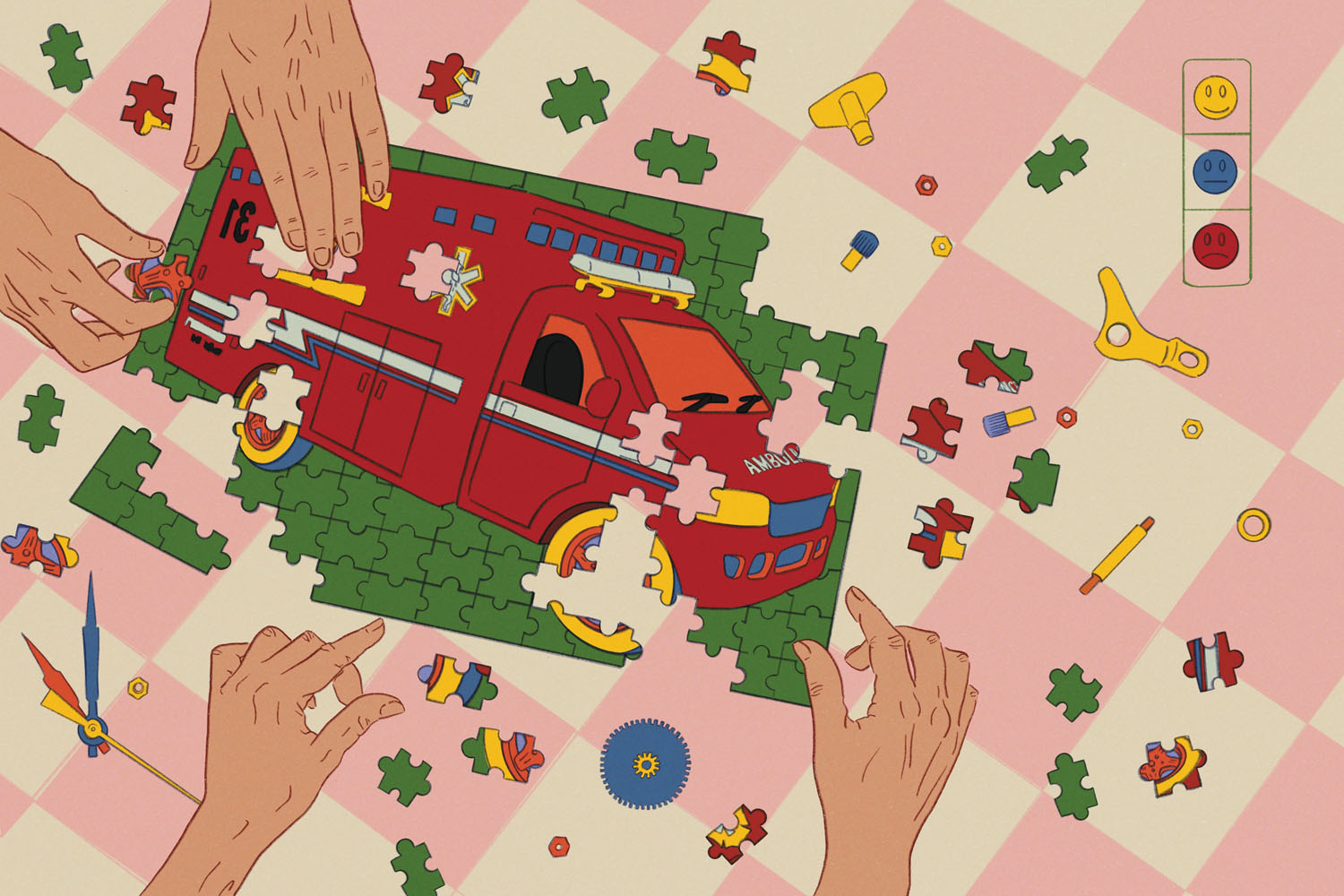

Nazila Jamalifard is an American-born illustrator and graphic designer of Iranian heritage based in New York. Her clients include the Nocturnists, Slmbr Prty, and Netflix.